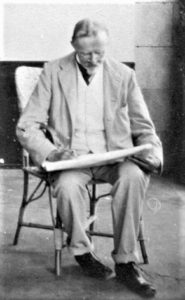

In September 2020, we were contacted by the philologist and historian Minas Chouvardas who is writing a book about past foreign travellers to the island of Karpathos. Minas is orginally from the village of Olympos, in the north of Karpathos, where the Bents spent Easter 1885. He was aware of the Bents’ important contribution to the documented social history of the island and has undertaken meticulous research into the events and the people described by both Theodore and Mabel in relation to Theodore’s article ‘On a far-off Island‘.

We were delighted when Minas offered us the chance to publish the results of his research on this website. His article precisely identifies individuals of whom Theodore only gave us vague details. Minas also investigates the murder which both Theodore and Mabel write about as having been instigated by one of their new friends while they were on the island. Overall, Minas’ article demonstrates his passion for the people, the places and the history of his native island.

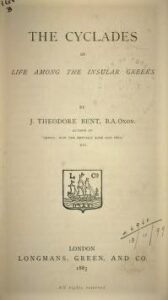

Minas’ article is best enjoyed when you have ready access to Theodore’s original account and, with this in mind, our sister website has published an ebook version of Theodore’s story which can be freely viewed online or downloaded in a choice of formats. Clicking on the book cover will open a new window so that you can flip back and forth between Minas’ and Theodore’s articles.

Minas’ article is best enjoyed when you have ready access to Theodore’s original account and, with this in mind, our sister website has published an ebook version of Theodore’s story which can be freely viewed online or downloaded in a choice of formats. Clicking on the book cover will open a new window so that you can flip back and forth between Minas’ and Theodore’s articles.

So, without further ado, let’s hand over to Minas:

The “Karpathiote” Friends of Theodore Bent – by Minas Chouvardas

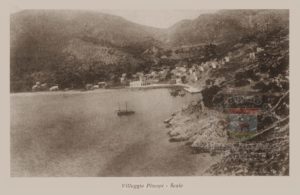

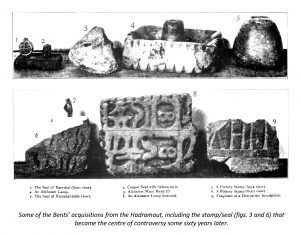

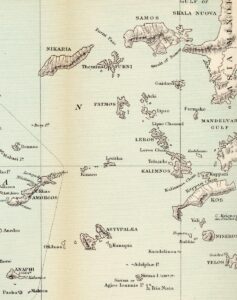

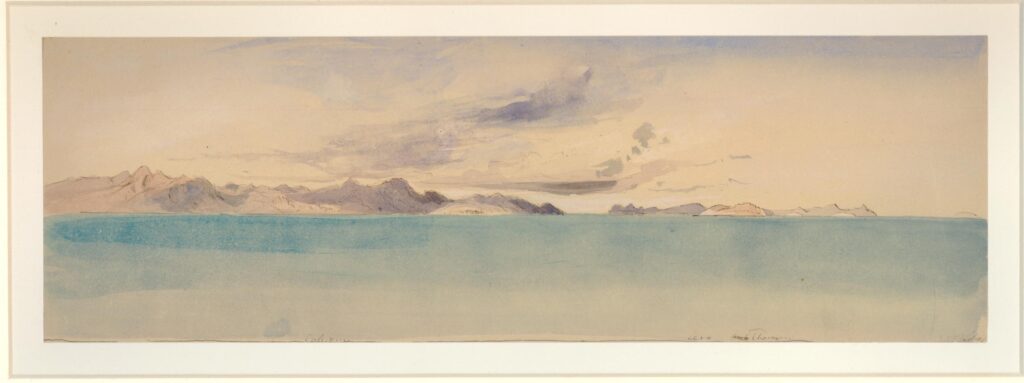

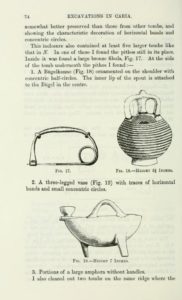

James Theodore Bent and Mabel V.A. Bent visited Karpathos in the spring of 1885 and remained on the island for about two months. Theodore Bent is the only foreign traveller to Karpathos in the 19th century who gives detailed information about the island’s ethnological composition, the archaeological findings, and the customs and traditions as he experienced them when he and his wife were there. He also gives detailed information about the Karpathian dialect, daily life, and the occupations of the inhabitants. Surprisingly, his important researches, which mainly concern the folklore of the island at the end of the 19th century, have passed unnoticed by modern scholars. Most Karpathian scholars know only of the contents of his extended article on Karpathos in the Journal of Hellenic Studies of 1885 note 1 . However, Theodore himself, when asked by his inner circle why he made the long journey to the remote island, and found so much of interest there, replied: “… it is one of the most lost islands of the Aegean Sea, lying between Crete and Rhodes, where no steamer touches, and … my wife and I spent some months on it last winter with a view to studying the customs of the 9000 Greeks who inhabit it, and who in their mountain villages have preserved through long ages many of the customs of the Greeks of old” note 2 .

You can read Mabel’s fascinating and informal account of the couple’s time on Karpathos in World Enough, and Time: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral

You can read Mabel’s fascinating and informal account of the couple’s time on Karpathos in World Enough, and Time: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I: Greece and the Levantine LittoralMabel’s narration in her Chronicles fascinates her readers, now as then, transporting them to the small, and poor, societies of Karpathos at the end of the 19th century. Thanks to the testimonies of the Bents, we share in the toils of the Karpathian farmers and shepherds, the art of embroidery, the love of song, of fun and dance, of food and drink, of the prejudices and superstitions. In all this there is the simple figure of the Karpathian: the mayor, the priest, the prominent man, the interpreter, the worker, the rower, the old prophet, the teacher, the old ‘witch’ with a remedy for every ill.

During their stay on the island they meet with several residents of Karpathos and with some of them they clearly developed friendly ties. Accordingly, this present article aims to introduce the Bents’ native friends and reveal information about their lives and personalities. Let us begin then …

Coming to Karpathos, the Bents carry three letters of recommendation given to them by the Greek consular agent of Rhodes, Mr. Philemon, addressed to three prominent Karpathians of that time: Mr. Frangiskos Sakolarides, Mr. Koumpis and Mr. Manolakakis.

The first friend that Mabel mentions in her “Chronicles” is Mr. Manolakakis note 3 . She does not mention his first name at any point in her diary, while Theodore in his article “On a far-off Island” never mentions his name, but always addresses him as “our third friend“. This fact suggests that the phrase is used ironically, as we shall see, by Theodore. The question that occurs to a modern Karpathian reader of Mabel’s diary is ultimately “who is Manolakakis?” The surname is found until today in the southern villages of Karpathos. Of course, many Karpathians on the island know that a Manolakakis, named Emmanuel, was the first historian and folklorist of Karpathos note 4 . However, other intrinsic items in Mabel’s diary make it possible to verify the identity of that person. Mabel reports that Mr. Manolakakis had lunch with them at least twice, that they bought Rhodian plates from his mother note 5 and that his then 17-year-old daughter Ephrosini (Mrs Sophrosine Manolakakis) helped the couple carry their luggage from Aperi to Volada note 6 . Mabel, unlike Theodore, seems to have liked Mr. Manolakakis, after stating, on the occasion of the help offered by Ephrosini, that “she is the daughter of a very nice man“ note 7 . She never mentions in her diary what topics of discussion they had, nor does she describe his appearance or character. However, Mabel, concluding the narration of their stay in Karpathos, notes in the form of a postscript that Mr. Manolakakis was the instigator of a murder committed in Volada while they were in Karpathos note 8 .

Theodore is more descriptive and revealing when referring to Mr. Manolakakis. He immediately shows his dislike when he mentions that Mr. Manolakakis was the reason they left Mr. Sakellaridis’ house in Aperi and went to Volada, so that he could carry out the assassination plan against the Karpathian “dragoman” Frangiskos Sakellaridis a few weeks later note 9 . When Sevasti, the owner of the house in Volada, refused to allow the couple to dance and sing, it was Mr. Manolakakis who supported Theodore and Mabel note 10 . Elsewhere in his story, Theodore points out the poverty of Mr. Manolakakis, who in order to marry his eldest daughter, gave almost all his property as a dowry, while his second daughter (Ephrosini) lived in misery note 11 . Theodore also mentions that Mr. Manolakakis had invited him for dinner, but because Theodore left before the fun peaked, he considers it possible that Mr. Manolakakis was misunderstood note 12 . Theodore, in contrast to Mabel, emphasizes the murder that took place in Volada, giving more details and without hesitation names Mr. Manolakakis as the instigator of the murder. What is striking is that Theodore three times in his narrative speaks of the attempted murder against the interpreter note 13 .

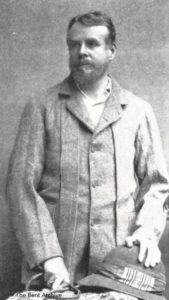

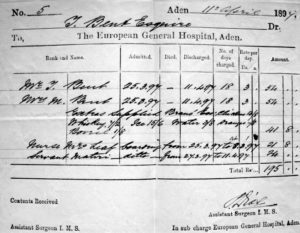

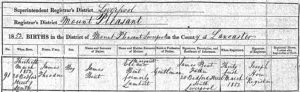

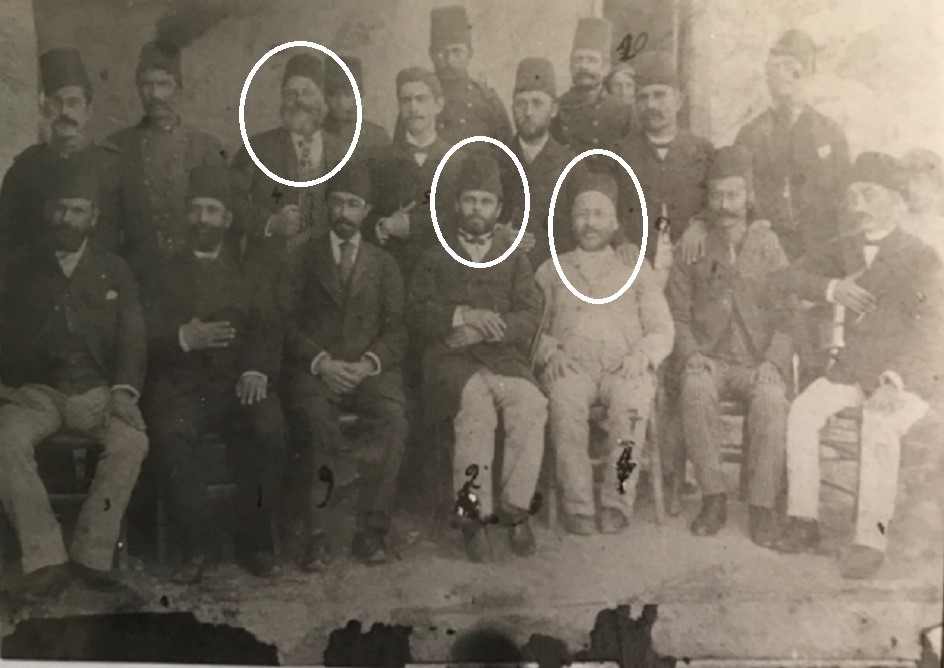

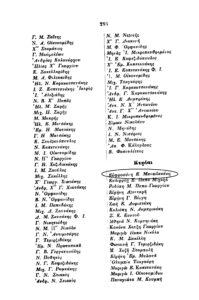

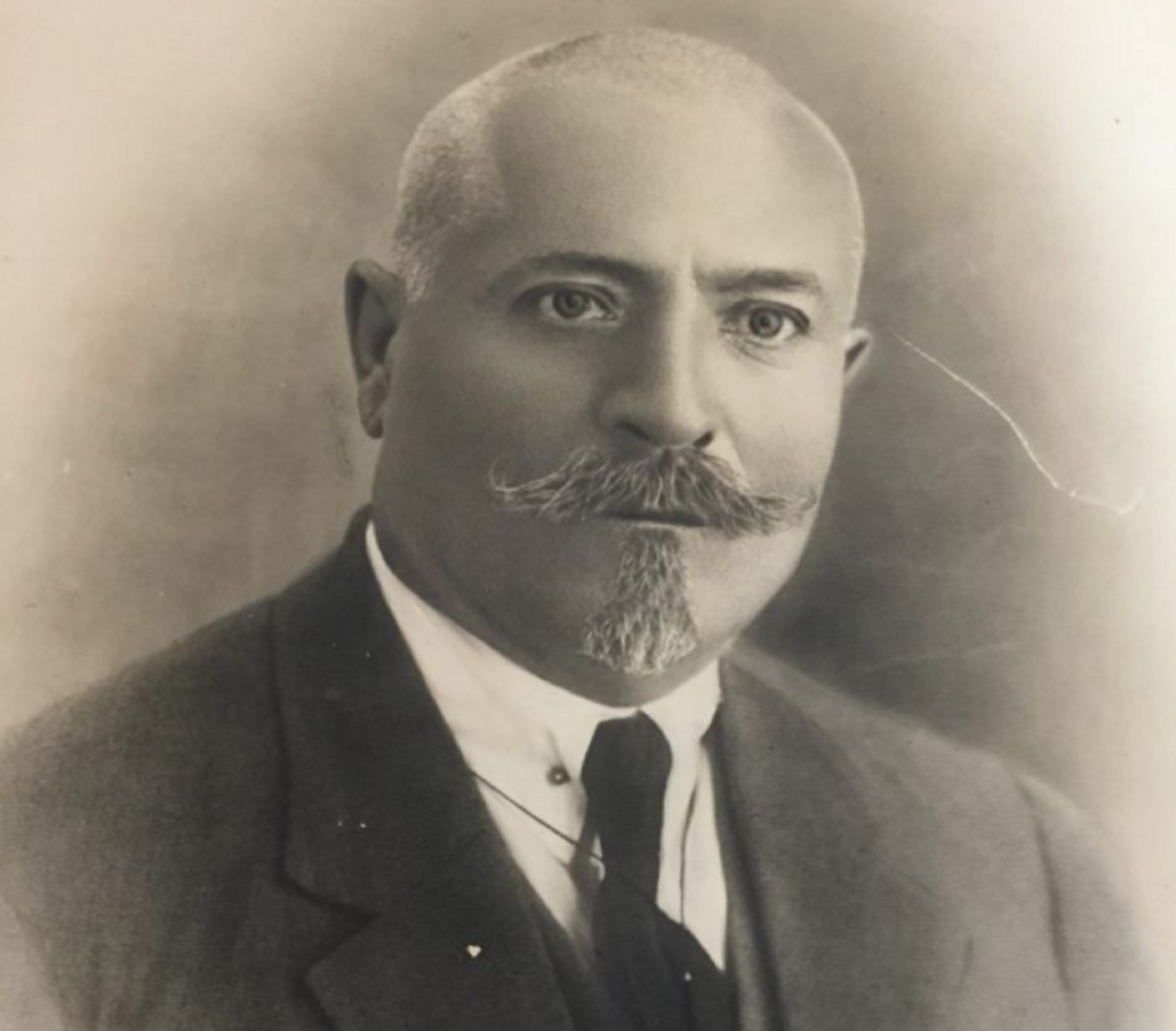

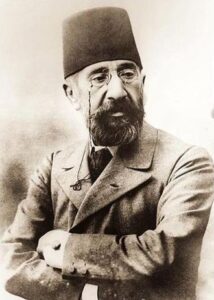

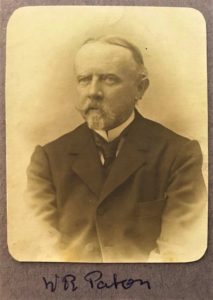

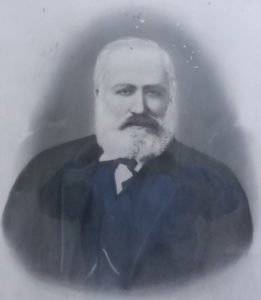

The “Mr. Manolakakis” whom Bent met is none other than Emmanuel Manolakakis, the author of Karpathiaka (1896). Emmanuel Manolakakis note 14 (fig.1) was born in 1830 and died on March 17, 1900 of a heart attack. He married Kalliopi Nikola and they had 11 children. He came from Volada and at the end of the 19th century he settled in Pigadia, where he served as mayor. He held Greek citizenship and was appointed in 1877, according to the testimony of his second son Georgios, consular agent of Greece in Karpathos. Manolakakis in Karpathiaka mentions T. Bent twice, describing him as a “wise” and “antiquarian” man note 15 . Ephrosini Manolakaki (Mabel refers to her as Sophrosini Manolakakis) was the fourth child of Emmanuel Manolakakis and the third of his daughters. She was born in 1868 and died in 1936 note 16 . In the list of subscribers of her father’s book Karpathiaka, only she appears to live in village Aperi note 17 (fig. 2). His second son Georgios (fig.3) served as mayor of Pigadia during the Italian occupation (1923-1933) note 18 , verifying Mabel’s prediction for Manolakakis’ children note 19 .

Bent’s second friend in Karpathos was Mr. Koumpis. Neither Mabel nor Theodore mention his first name. Theodore informs us that he was old and very talkative, and that of their three friends, only he was slow and late receiving them, due to a family problem note 20 . Mabel reports that on March 21, 1885, they went down to Aperi, met Mr. Koumpis and he then accompanied them to their home in Volada note 21 . This is the maritime art teacher Meletios Koumbis note 22 , who came from Megara, was in Karpathos, fell in love with Fotini Foka, the eldest daughter of Ioannis Fokas, the schoolmaster and mayor of Aperi, and settled in Aperi in the middle of the 19th century. He had three children with her, Kalliopi, Giannakis and Panagiotis. Bent reports that the year they visited Karpathos, Koumpis was an old man. He probably died in 1908 or 1909, because since then his name does not appear in the tax records of the municipality of Aperi, but the name of his widow does. The son that Theodore mentions as having recently married note 23 is Giannakis. Panagiotis (1869-1928) never married, but history recorded him as one of the best captains of Karpathos note 24 . Grandson of Meletios Koumpis and son of his daughter Kalliopi was the Karpathian hero pilot Panagiotis Orfanidis, who was killed in the Greek-Italian war note 25 .

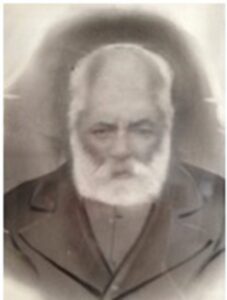

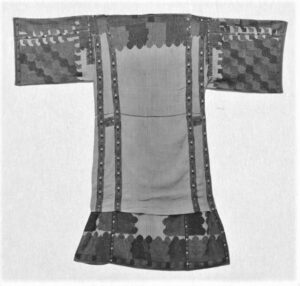

Bent’s third friend is named as Mr. Frangiskos Sakellaridis. Mabel pronounces and writes his last name as “Sakolarides”. Of the three persons mentioned, Mabel mentions the name (Frangisko) only in connection with Mr. Sakellaridis. On the contrary, Theodore always refers to him as “the interpreter“. Arriving for the first time in southern Karpathos, Bent spent two nights at his house in Aperi note 26 . He participated in the picnic at Kyra Panagia with his brother, while on his return to Volada, Frangiskos accompanied them to the village, offering them coffee at the café note 27 . On the first day the couple spent in the village of Elymbo, they found Mr. Sakellaridis chairing the village assembly note 28 . Theodore describes Sakellaridis’ very friendly relationship with his would-be assassin, while after the murder, where the wrong man was killed, Sakellaridis was always guarded by a Turkish soldier when he was outside note 29 . Frangiskos (Fragios) Sakellaridis (fig.4) note 30 (1847-1923) was the mayor of Volada and secretary of the Diocese of Aperi and was the youngest son of Georgios Sakellaridis from Aperi and Ernia Psaroudaki, daughter of the Cretan Georgios Psaroudakis who took refuge in Karpathos during the revolutionary period (1821-1830). The eldest son, Kostis (1844-1905), spoke and wrote the Turkish language fluently, serving in court positions (fig.5). Frangiskos married Rigopoula Kapetanaki and they had seven children. The eldest son, Georgios, was a doctor, while the second, Christoforos, was a teacher, secretary of the Holy Metropolis in Aperi and author of the proclamation of the Union of Karpathos with mother Greece (7/10/1944) note 31 . The son of Georgios and the eponymous grandson of Frangiskos was Frangios Sakellaridis (1897-1965), the doctor and brilliant scientist who dedicated his life to the health and well-being of his fellow citizens note 32 . In the year 1905, when the Turkish authorities tried to encroach on certain privileges granted to the islands ever since the time of Sultan Mahmud II (reigned 1808 – 1839), the Elders’ Council of Karpathos appointed Frangiskos Sakellaridis as a proxy to go to the Turkish governor of Rhodes and make the islanders’ case for the preservation of their privileges note 33 . Today, Volada’s football stadium is named after Frangiskos Sakellaridis (grandson of Bent’s friend).

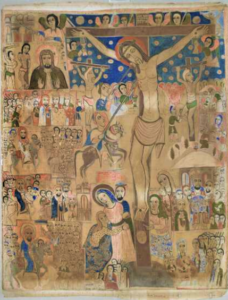

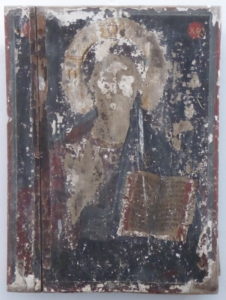

In the village of Elymbos the Bents were entertained at the schoolmaster’s house for the Easter period note 34 . Neither of them mention his name. In fact, Theodore in his article “A Christening in Karpathos” confuses him with the schoolmaster of the village of Mesochori, referring to Mabel’s anecdote about Jules Verne note 35 . From Mabel we learn that he had two little girls, “Maroukla” (Maria) and “Eirenio” (Irene) and that the mayor of the village, “Diako-Nikolas”, was his father-in-law note 36 . The schoolmaster that Theodore encounters in the café (kafeneion) and finally stays with in Elymbos, was the first “Greek teacher” Nikias Ioannou-Spanos note 37 , who was the first to organize the archives of the community and contributed hugely to the standard of education of the children of Elymbos (fig.6). Nikias Ioannou-Spanos was born in Kalymnos around the year 1837. His real last name was Spanos, however he became known by his patronymic (Ioannou). He came to Karpathos in the early 1860s, when the mayor of Elymbos, Diako-Nikolaos Diakogeorgiou, was on the island of Kalymnos to find a suitable schoolmaster for his village. His good luck leads him to Nikias Ioannou-Spanos, whom he hires as a teacher of Elymbos. Nikias, around the year 1876, will marry one of the daughters of Diako-Nikolas, the youngest girl, Magafoula, and they will have six children, Ioannis, Nikolaos, Georgios, Maroukla, Rinio and Evangelia. The two older daughters are mentioned by Mabel. His fame spread throughout Karpathos and apart from Elymbos, he taught in Aperi (1870, 1885-1888), Menetes, Kasos, Rhodes and Kos. The last years of his life he lived in Diaphani, where he died and was buried in the spring of 1923 at the age of 85-86. His family tradition states that his last words were that he was dying without being able to see the Dodecanese free at last.

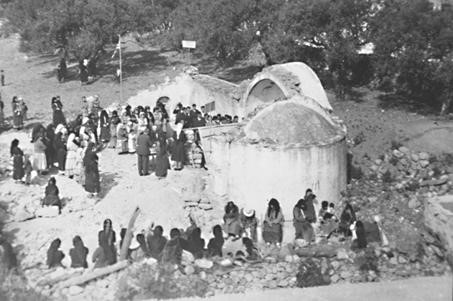

The Bents also met other residents of Karpathos with whom they had friendly (or non-friendly) relations. They, of course, met the Turkish governor of the island (the kaimakam) and his clever secretary Hassan Efendi (fig.1) note 38 . At the village of Spilies they met Mrs. Chrysanthi or Chrysanthemou note 39 . In Arkasa, Menetes and Mesochori they were put up by local residents. Finally, in Diaphani, they were hosted for five nights at the house of Protopapas note 40 . Unfortunately the Bents give few details about these personages, making it almost impossible to identify them today. Only for the latter, Protopapas, is it known that his family owned the church of “Panagia” in Diaphani. On February 9, 1948, a strong earthquake, measuring 7 on the Richter scale, shook Karpathos and the settlements of the island suffered severe damage – Diaphani’s old church collapsed and the modern church was built on the site in the 1960s (fig.7).

As for the murder in Volada, it has been long forgotten by the collective memory and no one in Karpathos knows or has heard of it. No contemporary Karpathian writer ever mentions anything about the event. Manolakakis, the instigator of the crime according to Bent, on the contrary states that murder on the island is almost unknown, and if it ever happens it is due to the greatest provocation or revenge note 41 . Τhe greatest historian of Karpathos, M. Michailidis-Nouaros (1879-1954), although he lived close to the event, makes no mention. Τhere is only the testimony of the Bent couple about this event that shook the local community of Karpathos in the spring of 1885. From an historical point of view, of course, the testimonies of Mabel and Theodore still need to be corroborated by other sources, but considering overall the Bents’ extensive writings on the events they experienced on their almost two months on the island, their accounts have proved to be highly reliable.

If you have more to add, do please get in touch.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this articleNotes to The “Karpathiote” Friends of Theodore Bent

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

Return from Note 8

Return from Note 9

Return from Note 10

Return from Note 11

Return from Note 12

Return from Note 13

Return from Note 14

Return from Note 15

Return from Note 16

Return from Note 17

Return from Note 18

Return from Note 19

Return from Note 20

Return from Note 21

Return from Note 22

Return from Note 23

Return from Note 26

Return from Note 27

Return from Note 28

Return from Note 29

Return from Note 30

Return from Note 31

Return from Note 33

Return from Note 34

Return from Note 35

Return from Note 36

Return from Note 37

Return from Note 38

Return from Note 39

Return from Note 40

Return from Note 41

For the Bents generally in the Dodecanese, see Further Travels Among the Insular Greeks (Archaeopress, Oxford)

Incidentally, the Bents never opted to explore Crete, although we know Mabel spent the winter of 1899/1900 there. Perhaps the work of Arthur Evans on the island dissuaded them!

We’re always searching for more information on the topics and people we write about. Can you add more information about Kyra Panagia or old Vasilis, or about the Sakolarides or Mr. Manolakakis? Please contact us using the ‘Comment’ form on this page or on our

We’re always searching for more information on the topics and people we write about. Can you add more information about Kyra Panagia or old Vasilis, or about the Sakolarides or Mr. Manolakakis? Please contact us using the ‘Comment’ form on this page or on our