In July 1895 Mabel and Theodore Bent gave an interview to The Album: A Journal of Photographs of Men, Women, and Events of the Day (8th July, 1895, Vol. II, No. 23, pp.44-45). Published by Ingram Brothers (Strand, London), it was a short-lived venture (the market was extremely competitive); a browse through a collected volume gives an unsurprising but fascinating glance back to Victorian Britain at its zenith.

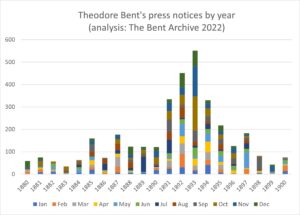

Zenith can equally well be applied to the fame of the Bents in 1895 – they were celebrities. They had more or less covered the Eastern Mediterranean by the end of the 1880s; ridden south-north the length of Persia (1889); had famously explored the ruins of Great Zimbabwe for Cecil Rhodes (1891); become entangled in the Italian debacle in Ethiopia in 1893; and were now (1895) obsessed with Southern Arabia – their work in the region was to provide the data for Theodore’s great quest of a history linking both sides of the Red Sea over three millennia. This was not to be however – within three years of the article you are about to read, Bent was dead, a victim to feverish malevolence, east of Aden, in the spring of ’97.

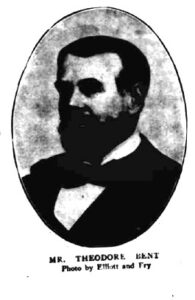

Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent

Since the days when Sir Walter Raleigh returned from the West Indies laden with good things, down to our own unromantic time, there have always been a large number of large-hearted Englishmen who have devoted their lives, fortunes, and too often their healths, to exploring the little-known corners of the earth with a view to increasing our knowledge of far-off climes, and of adding to the instructive contents of the British Museum and of the other vast treasure-houses possessed by the nation. note 1

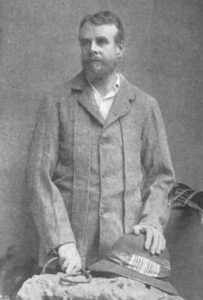

Mr. J. Theodore Bent has played a leading part among latter-day travellers. Accompanied by his plucky and charming wife – nee Miss Hall Dare of Newtonbarry, Co. Wexford – note 2 he has explored in turn many pathless portions of the uncivilised world, to say nothing of his valuable researches into the bygone civilisations of Greece, Asia, and Africa.

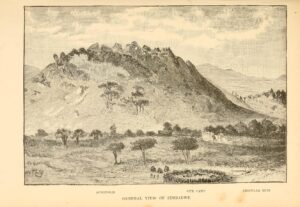

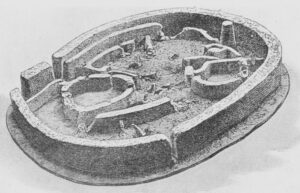

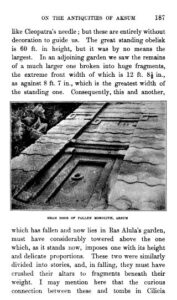

Each one of Mr. and Mrs. Bent’s expeditions has hitherto resulted in a valuable addition to geographical and archaeological literature, and the former’s book, dealing with the famous ruins of Zimbabwe, was the first and in many respects the best, account of Mashonaland published.

The well-known explorer and his wife have lately returned from their second journey into Arabia, and I found them, (writes a representative of The Album), settled for the season in their museum-like London home, a house filled with momentoes of my hosts’ many years of travel, from Greek antiques to the barbaric, if splendid, gifts of his Arab Sheikh friends. note 3

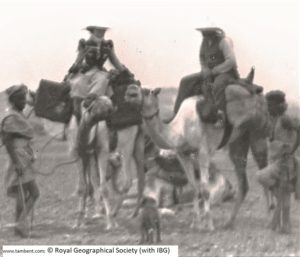

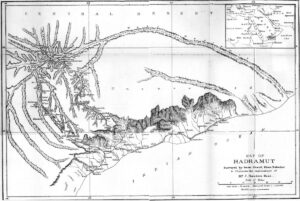

“And what were the practical difficulties in the way of an Arabian expedition?” “Owing to the slave trade the Arabians are not at all anxious to have their dark ways made light. Each district is governed by a Sheikh, and the country is in a wild a lawless state. Indeed, Arabia was far more civilised before the rise and spread of Mahommedanism. I traced many of the ancient Sabæan fortresses and towns, and found most interesting inscriptions. We entered Arabia by Merbat, and thanks to the European resident in Muscat, got on fairly well, but of course in the interior our means of getting about was by the help of camels only used to carry frankincense.”

“And what did you take in the way of provisions, and so on?” “I always leave the commissariat side of our journeys to my wife,” answered Mr. Bent, smiling. “She sees after everything of the kind; but as to food, there is one point I should like to mention. I am a thorough believer in tea, and do not advise anyone to explore on spirits, although on this last expedition we took a little rum much over proof to dilute. Then, of course, quinine is the best travelling medicine in the world.”

“Our exploration larder”, added Mrs. Bent, “is quite varied enough for all reasonable requirements; desiccated soups, corned beef and beef essence, potted meats, condensed milk, and last but not least, some sackfuls of dry bread, are all included, for long experience has taught us both what to avoid and what to add to our travelling impedimenta. note 5 We always try to be as comfortable as possible when journeying, and so take plenty of sheets and towels; but, of course, the lack of water is a great annoyance. By-the-way, we always travel with one of Edgington’s green fly-tents, with double flaps, the whole made of the green Willesden canvas which does not get mouldy when folded up wet.” note 6

“And are you accompanied by a large party?” “During our last journey we were eleven in all; my husband and I were the only Europeans among them. There is no use in taking English servants. Of course this increases danger in uncivilised countries. Constantly on our travels the Bedouins with whom we have been travelling have turned against us, and on one occasion we seriously thought of trying to find our own way to the coast alone.”

“And have you any views on the best travelling costume?” I enquired. “Yes, inasmuch that we do not alter or modify our travelling costumes, wearing the same kind of clothes in both Africa and Asia. My husband finds a Norfolk jacket and breeches the most practical and pleasant form of dress for either riding or actual exploring work. My travelling dress consists of a tweed coat and skirt, a pith hat, with breeches and gaiters. The skirt is made in pleats, and is so arranged as to act as riding habit when I am on horseback. When actually in camp, that is to say, during the heat of the day – for early morning and evening are the only safe hours to travel – I put on a linen shirt or blouse and ordinary skirt.” note 7

“And on the whole, what is your verdict on the various countries you have so successfully explored?” “South Africa is, undoubtedly, the land of the future,” answered Mr. Bent decidedly. “Perhaps you know that in 1891 we explored the ruined cities of Mashonaland, the Royal Geographical Society and the British South Africa Company aiding us in paying the expenses of the expedition? note 8 Our experience while in the interior taught us something of the possibility of Rhodesia, and I think that an energetic emigrant has as a good chance there as anywhere else; but of course opinions differ. I myself fell a victim to South African fever, but I have noticed that this kind of disease disappears with civilisation, and my views have been thoroughly borne out in the case of Kimberley.” note 9

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

Return from Note 8

Return from Note 9

[You may also enjoy the two interviews Mabel gave to Lady of the House in 1893 and 1894]

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article