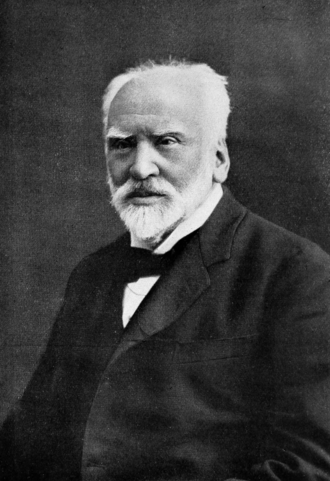

Theodore Bent had a good friend in Sir Edwin Pears (1835-1919), a British barrister, author and historian, whom the Bents met in Constantinople (although here our interest is on the Cycladic island of Amorgos).

Neither in his book The Cyclades, nor in his Easter article, does Bent make it clear whether his wife Mabel was with him on Amorgos in the Spring of 1883 or not. Indeed, in his 1884 article he ends: “Next day the relentless steamer called and carried me [our italics] off to other scenes.” It is rather a mystery.

We do know, however, that Bent did travel on his own for his second visit to the island in early 1884, Mabel deciding to stay on Paros/Antiparos, feeling below par (see The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Vol. 1, 2006, p. 46, and our earlier article on Amorgos at Easter 1893).

Now, interestingly, a section in Edwin Pears’ (1835-1919) book on Turkey (1911) seems to suggest that Mabel was with Theodore on Amorgos in 1883 (their first visit to the Cyclades). Pears, a good friend of the Bents, recalls a folkloric episode from the island told him by the explorer, which, it seems, was never published; it is therefore a noteworthy addition to Bent’s adventures on Amorgos and should be included with Bent’s publications on that Cycladic place (and, of course, within his collected writings on customs and traditions generally).

Here is what Bent’s Amorgos amigo has to say:

“I conclude this notice of surviving paganism by telling a story for which my authority is the late Theodore Bent. In his interesting book on the Cyclades, his last chapter, full of good matter, is about the island of Amorgos at the south-east end of the group he has been describing. The following story is not in it, but was told me by him shortly after the incident occurred; and Mrs Bent, who nearly always accompanied her husband, has kindly informed me recently that it was on Amorgos where the incident happened. Mr Bent had so often found that the customs mentioned by Herodotus were continued to the present time, that he incautiously asked the priest of St Nicholas, the successor of Poseidon as the protector of sailors, whether the old practice of divination by tossing up knucklebones and learning by the way in which they fell on the altar what the direction of the wind would be, still continued. The answer was in the negative. When the priest turned away, an old woman who had overheard the conversation said to Mr Bent, ‘All the same, Chilibé [sic], no ship goes to sea without the crew coming here to learn how the wind will blow.’ Mr Bent said nothing, but having learned that two or three days later a vessel had arranged to leave, watched her crew, and having seen them start on their way to the church, followed them at a distance, taking care to keep out of sight. They entered the church, and five minutes later were followed by Mr Bent, who arrived just in time to see, through the holy gate, candles lighted upon the altar, the priest with his hat off, and his long hair down, and in the very act of tossing the knucklebones.”

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this articlePears also makes a glowing reference to his friend Bent in his The destruction of the Greek empire and the story of the capture of Constantinople by the Turks (1903, p. 449, fn. 1): “Mr. Theodore Bent, who had paid greater attention to the archaeology of the Greek Islands and to their present condition than any other Englishman…”