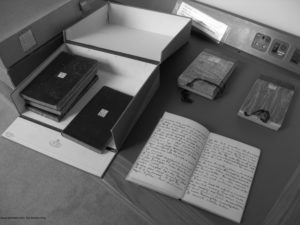

“The beauty of her hand, the delight of seeing through her eyes, the little bits inserted between the pages or pinned to the leaves. Reading through the journals was a treat beyond the academic. Thank you for making the journals more widely known…” Mabel’s ‘Chronicles’ in their three storage boxes within the archives of the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies, Senate House, London (review and photograph kindly provided by David Maltsberger, December 2018).

From early 2022 Mabel’s ‘Chronicles’, have now been scanned and are available on open access. In the words of the Curator of the project for the Hellenic Society (Sept 2021):- “The digitisation project encompasses several collections here at the library; most notably … the Bent Collection .. which contains the travel diaries of Mabel and Theodore Bent, who travelled in Greece and the Middle East in the late 19th century.”

This is an incredible advance and now makes Mabel’s original work in the Levant, Africa, and Arabia available to scholars and interested travellers. (Printed and online transcripts remain available from Archaeopress, Oxford.)

“[Tuesday] February 2nd [1886]. Hôtel de Byzance (No 2) Constantinople. I must begin my Chronicle somewhere if I am to write one at all, and as in this matter I am selfish enough to consider myself of the first consideration, because I write to remind myself in my old age of pleasant things (or the contrary), I will begin now…”

There is a note in with the collection of notebooks in the Hellenic Society Archive recording that the volumes have come ‘from Mrs. ffolliott’. This lady is Violet Ethel ffolliot (1882-1962, née Bagenal), daughter of Ethel Bagenal (née Hall-Dare), Mabel Bent’s sister. Violet was hence Mabel’s niece; she married Colonel William Hovenden ffolliott on 8 December 1920. There is no record of when the notebooks were presented, presumably shortly before or after Mabel’s death in 1929, the latter’s nieces, it seems, disposing of her property. (The notebooks covering the Bents’ explorations in Ethiopia in 1893 are missing.)

Click here for an index and guide to finding your way around Mable’s Cyclades notebook of 1883/4.

Printed editions of Mabel’s Chronicles are available from the Archaeopress Online Shop.

Read on! And if you enjoy Mabel’s Chronicles posts, why not sign up to receive future ones via Facebook, Twitter or email, and tell your friends! Become Bentophiles and join them on their travels in the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa and the Near East.

BENT, Mrs. Mabel Virginia Anna, of 13, Great Cumberland Place, W., and of the Ladies’ Empire Club, is a daughter of Robert Westley Hall-Dare, D.L., of Theydon Bois, Wennington Hall, Essex, and Newtownbarry House, Co. Wexford. She was married Aug. 2, 1877, to the late Theodore Bent, of Baildon House, Yorks. Mrs. Bent accompanied her husband in all his explorations , and took part in the excavations with which he was associated in the Greek and Turkish Islands, Asia Minor, Abyssinia, the Great Zimbabwe (Mashonaland), Persia, and elsewhere. She is the authoress of Southern Arabia, Soudan, and Sokotra, compiled from her own and Mr. Theodore Bent’s notes. [Anglo-African Who’s Who, 1907]

1893. From the studio of H. S. Mendelssohn, South Kensington © Gerald Brisch

By ‘notes’ in the Who’s Who extract above, we are perfunctorily introduced to the extraordinary series of notebooks Mabel diligently kept for the fifteen years or so that she and Theodore travelled together in the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and the Near East (1883-1897). She called them her Chronicles and what follows, by way of a little background, is taken from the Introduction to the 2006 edition of Mabel’s notebooks (Archaeopress, Oxford) covering the Bents’ travels in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In the fifth decade of Victoria’s reign, two paths brought together an indefatigable Anglo-Irishwoman of means and an Englishman of mettle; on the second of August 1877 they married. The newly-weds, she thirty-one, he twenty-five, moved to live in London, a stone’s throw from Marble Arch, at 13 Great Cumberland Place, W., and within a few months the couple were off on a series of inseparable, breathless, annual trips that were to continue until, twenty years later, on the fifth of May 1897, the Englishman, an ‘archaeological adventurer’, died from malarial complications, and Mabel Virginia Anna Bent found herself once more on a solitary path, left with her memories and an assemblage of travel Chronicles, that she ‘always wrote during their journeys’ (and which are complete except for the account of the couple’s adventures in ‘Abyssinia’ in 1893) .

After her death, formidable and eighty-three, in 1929, these Chronicles in the form of two dozen small leather notebooks found their way into the archive of the Hellenic Society, out of the light and overlooked. These are the journey accounts of Mr and Mrs J. Theodore Bent. And what journeys.

Sooner or later, today’s tourists who venture as far east as Karachi, south as Cape Town, west as Lisbon, north as Warsaw, will undoubtedly find themselves on a route once followed by the Bents.

Before the invention of flight, they were amongst the the most-travelled husband and wife teams of their generation: the coverers of goodness knows how many equivalent circuits around the globe by ship, train, carriage and cart, on horse, camel, mule or donkey, and, of course, on foot. Thousands of miles under hot sun, nights under canvas, in regions where every other European might expect to have his or her life drastically shortened by illness or injury: as was the fate of Theodore … at the age of forty-five. And the reasons for all this effort and expense? Their objectives? The modern bibliographies that have to do with archaeology, anthropology, ethnography, botany, and other fields with similar suffixes, in regions from Abyssinia to Zimbabwe, are still very likely to refer to the articles, papers and monographs of Bent, J. Theodore, and, occasionally, Bent, Mrs J. Theodore. In addition they were alert commentators and observers, they enjoyed their food and drink, music, customs and costumes. They also felt they had a duty to minister to the sick as much as they could – with a great medicine chest full of arrowroot, brandy, quinine, and demijohns of Brand’s Beef Tea. They were fortunate; they were comfortably-off Victorians (their atlases were stamped the colour of their monarch’s soldiers’ jackets) and, blessed with extraordinary stamina, they had world enough, and time … before the great wars.

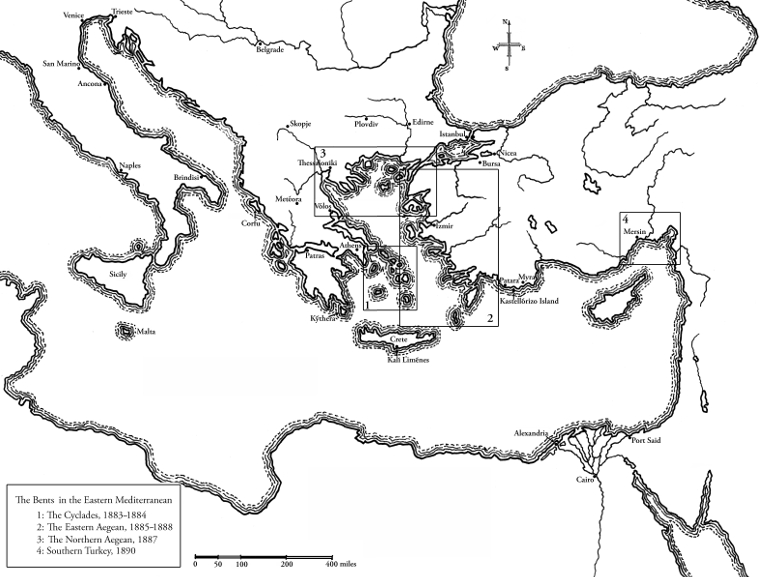

In pursuit of their researches, their reputations increasing with each campaign, the Bents preferred to travel abroad during winter and spring, returning to London (and from there making shorter journeys to see friends and family around Ireland and the English countryside) for long, pleasant summers, and to write up their findings, lecture, and plan next season’s adventure. Mabel’s Chronicles provided Theodore with much of the background material he was to use for his monographs and articles. A look at his long list of publications brings into focus three concentric, geographical circles – the Eastern Mediterranean (Greece and Turkey), the greater continent of Africa, and the Near and Middle East. And this is how his wife’s travel Chronicles are presented.

In pursuit of their researches, their reputations increasing with each campaign, the Bents preferred to travel abroad during winter and spring, returning to London (and from there making shorter journeys to see friends and family around Ireland and the English countryside) for long, pleasant summers, and to write up their findings, lecture, and plan next season’s adventure. Mabel’s Chronicles provided Theodore with much of the background material he was to use for his monographs and articles. A look at his long list of publications brings into focus three concentric, geographical circles – the Eastern Mediterranean (Greece and Turkey), the greater continent of Africa, and the Near and Middle East. And this is how his wife’s travel Chronicles are presented.

Mabel Bent died at 13 Great Cumberland Place, W, on the fifth of July 1929 at the age of eighty-three. Her Times obituary (6 July 1929) includes that, as an experienced photographer and accurate observer, she was of enormous assistance to her husband and ‘famous for the explorations in distant lands which she undertook with [him]. This was at a time when it was much more rare than it is now for a woman to venture forth on such journeys […] During her long widowhood of more than 30 years Mrs. Bent was well known in literary and scientific London. She was a good talker, with an occasional sharpness of phrase which was much relished by her many friends.’

And would there be any ‘sharpness of phrase’ about seeing her Chronicles in print? Did Mabel intend them for publication? Apart from the fact that Theodore relied on the leather notebooks for the provision of background details in most of his publications, the chronicler has left one or two clues within her pages. From Room 2 of the Hôtel de Byzance, Constantinople, in February 1886, Mabel confides: ‘I must begin my Chronicle somewhere if I am to write one at all and as in this matter I am selfish enough to consider myself of the first consideration because I write to remind myself in my old age of pleasant things (or the contrary) I will begin now.’ So we know, at least, that they were for her to read later in life, and that she intended her aunts, sisters, and nieces to share her adventures. (There are several asides such as, ‘We have constant patients coming to us and I am sure you would all laugh to hear T’s medical lectures.’ And ‘You must excuse these smudges as I am sitting cross-legged on T’s bed.’) There is also certainly nothing in the millions of words that could be classified as terribly indiscreet, let alone anything close to libel – or nuptial intimacy for that matter, although there is a little false modesty and coquetry here and there. (There are only two or three references to ‘headaches’ and nothing on what might be described as natural inconveniences.)

But the most obvious hint that Mabel, at the very least, might be aware of a potential wider interest in her Chronicles is the letter still preserved (in the 1885 volume) from family friend, Harry R Graham, complimenting her thus: ‘I carried off your Chronicle … and … I never enjoyed three hours more than when reading it in the train coming down here yesterday – as soon as I have finished it I will send it you back – but why oh why don’t you publish it? It simply bristles with epigrams and I am certain would be a great success! You ought to blend the 2 Chronicles into one and I am sure everyone would buy it.’ (Letter, 23(?) December 1885, Hellenic Society, Hellenic & Roman Society, London)

Well. Perhaps not everyone. Mabel’s Chronicles are not great travel literature. They are her on-the-spot recollections of long days spent trekking, exploring, digging, dealing with villagers, arguing with minor officials; they are snatches of gossip, snobbishness, likes and dislikes, barking dogs, vicissitudes, poverty and pain; they are delightful souvenirs of music, dancing, colourful costumes and wonderful meals. Great travel literature? No. But great travel writing – accounts of wonderful endurance and a reflection of courage, attitude, apogee of empire, and spirit – most certainly. Chronicles any of us, openly or secretly, might have been happy to write, had we but world enough, and time. You can read more about the issues and considerations involved in the transcription of the Chronicles.

Before we join Mabel in her travel Chronicle of the Cyclades, there are a few last-minute details to attend to. It is Mabel’s practice to refer to her husband as T throughout, and their Greek assistant, Manthaios (who replaces later the below-par Phaedros), as M. The first Chronicle is written in a lined and columned accounts book (£/s/d, of course); it has marbled endpapers and edges and measures 175 x 110mm. Mabel completes 94 of its 130 leaves. The book once belonged to Theodore and he has written in the back of it ‘J. T. Bent. Acct. Book. Oct. 13th 1871’. He would have been nineteen and about to enter Wadham College, Oxford. It is as if, just before they set out for their second trip to Greece in November 1883, one of the couple hits upon the idea that Mabel should keep a record of the trip, and a simple, dark-red leather notebook that has been lying around the house for twelve summers is the first thing that comes to hand. But from this inconsequential idea flows a fifteen-year stream of travel diaries unparalleled in their scope and addictive in their appeal.

We hope you will enjoy the following, irregular posts of Mabel Bent’s travel Chronicles.

© Gerald Brisch, September 2006 & November 2016.

Some reviews of Mabel’s published Chronicles

‘Volume I, Greece and the Levantine Littoral’, reviewed by Paul Watkins, in Anglo-Hellenic Review, 2006, pp.31-32.

‘Volume II, The African Journals’, reviewed by Thomas N. Huffman, in Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 2013, DOI: 10.1080/0067270X.2013.852379.

‘Volume II, The African Journals’, reviewed by John C. Mitcham, in African History 55(2), 2014, pp.296-298.

‘Volume II, The African Journals’, reviewed by Robert Witcher, in Antiquity 88, 2014: 1357-8.

‘Volume III, Southern Arabia and Persia’, reviewed by Nicole Chevalier, in Bulletin for the Study of Arabia 16, 2011, 53-54.

‘Volume III, Southern Arabia and Persia’, reviewed by Mary Henes, in Astene Bulletin 47, Spring 2011, 9-10.

We can begin, at last, Mabel’s Cycladic Chronicle, her first, in Athens on Monday, 26 November 1883, at the Hôtel des Etrangers, or, you can view all Mabel’s Chronicle blogs that we’ve published to date.