‘The Hadramaut’ – December 1893 to March 1894

By the time Mabel begins her Yemen Chronicle, nearly four busy years after the Persian tour described above, the couple have become well-known explorers, thanks in part to one of the great figures of the moment – Cecil Rhodes. Theodore was without a major research focus after his final trip to Turkish littoral in 1890 and a series of events (detailed in African explorations) catapulted the couple into the lands recently annexed by Rhodes (Zimbabwe) to survey the extensive ruins at ‘Great Zimbabwe’. Theodore would not have required much persuasion. He was in search of a coherent field of study (he had not published a monograph for six years) where he could work without hindrance, and he was fascinated by the early circulation of populations from the Levant, Arabia and the Middle East: his recent work in Bahrain was partly inspired by ancient theories that the island was the early home of the Phoenicians. That the trading and expansionist drive of these peoples should have led them to southern Africa was also to provide Theodore and Mabel with much of their motivation to make for Great Zimbabwe in January 1891.

As well as being an extraordinary travel story in its own right (by ox cart and returning by sea, along the South African coast), and notwithstanding his now discredited interpretation of the ruins, the expedition was a pivotal moment in terms of Bent’s career as an explorer/archaeologist: his work can be divided into pre- and post-Mashonaland. All the couple’s researches afterwards were linked to Theodore’s studies and theories of early communications between civilisations living west and east of the Red Sea, especially Southern Arabia. It was from here, Theodore claimed, that the builders of Great Zimbabwe came – in furtherance of their trading initiatives.

The couple arrived back from Africa in 1892 with an unusual collection of material from Great Zimbabwe and they exhibited most of it at first in their London home, before the artefacts were acquired by the British Museum. Theodore was immediately extremely busy writing and lecturing on his African expedition. By the end of the year his monograph (The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland) was published and had reached its third reprint by 1902. This work, the most commercially successful of his four travel books, cemented his reputation as one of Britain’s most prominent explorers (and widely-liked on a personal level) – although by no means an uncontroversial one, nor one embraced generally by the academic establishment.

Drained after Africa, but apparently well, the couple limited the remainder of 1892 (some ten months, and the longest sustained time they had remained north of the Channel for at least ten years) to family visits in Ireland and the north of England, and de rigueur events such as prize giving at Macclesfield Grammar School and the Royal Geographical Society’s Banquet (London, Monday, 23 May 1892): ‘It is five or six years ago since the Royal Geographical Society, for some unexplained reason, gave up a custom which had been sanctioned by many years of success. The annual dinner, at which formerly all who were interested in the many-sided study of geography were wont to be assembled, has this year been revived under the presidency of Sir Mountstuart Grant-Duff, who occupied the chair this evening at the Whitehall Rooms of the Hotel Metropole… Of travellers there was of course a large number present. Mr. Stanley was not in the toast list, but a passing reference to his presence in Mr. Whymper’s speech was made the opportunity for a generous recognition of the distinguished traveller. Mr. Theodore Bent… and a host of other travellers… were scattered about the room…’

For their 1893 season Theodore and Mabel headed north into the Horn of Africa, looking for possible clues in the civilisation of the early Ethiopians that might link Great Zimbabwe to the old trade routes that led into Egypt to the west and Southern Arabia to the east. Clues would include early ‘Arabian’ (Sabaean primarily) inscriptions from ancient Aksum (its royal family claiming descent from Menelik, the son of the Queen of Sheba, who had the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem hidden in his capital). This short (and arduous) exploratory period in Abyssinia/Ethiopia provided Theodore with inscriptions and other finds that seemed to give his theories further support regarding trade routes (and at this stage it seems he developed an extra interest in luxurious resins, particularly frankincense, and spices) moving east-west across the Red Sea and centred on the early-first-millennium societies of the modern southern Arabian peninsula.

Their route home that year was via the strategic British outpost at Aden, and it was here that Theodore seems to have been given information and sources regarding British naval surveys of the coastal waters leading east (modern Yemen and Oman) and the spectacular nature of the interior. The explorer’s first discussions in Aden determined his final years of research: at the end of 1893 he and Mabel began the series of explorations to challenging areas of Southern Arabian that were to occupy them until Theodore’s death in 1897.

Back in London, Bent writes to the offices of the Royal Geographical Society:

‘Dear Mr. Freshfield… On our way back from Abyssinia we called at Aden with a view to making enquiries about the possibilities of visiting Yemen next winter… As the governor and military authorities gave us every encouragement we have decided to do so. Entering Arabia by Makalla and under the protection of that Sheikh going inland and along the Hadramaut coast as much as possible… Besides my own special object of archaeology I hope we may be able to do some geography in that district and with this view I am writing to ask if you will put it before the council and ask for a grant with this object in view… As we leave in November I thought it best to bring this question before the Society during this session… Yours very truly, J. Theodore Bent’

There were ever geo-political tensions in the region. The British, or East India Co., occupied Aden in 1839 in their quest for a suitable coaling station on the route to India via Suez and established a series of loose zonal alliances to enhance their influence. Eventually, the route to India and Australia via the Suez Canal made Britain’s Red Sea interests crucial, arguably more important than the earlier overland route through Persia. The greatest diplomatic skills were required to manage the ebbs and flows of relations with the Ottoman Empire and the Porte. After the occupation of Aden, British policy, although preferring tribal independence, was generally one of non-intervention in Arab affairs, extending to various alliances with the many regional (and often feuding, as the Bents were to find out) tribes. Initially this policy was satisfactory during the decades when local rulers felt themselves independent of the Ottomans, but when, in the early 1870s, they began to feel at risk they turned to British Aden for support and at this time an interventionist policy in tribal affairs was put into effect. Seeing opportunities to expand their own ambitions the area became a focal point for the ambitions of other European powers. As a response, in February 1886, the Government of India sought to secure South Arabia by a series of protectorate treaties (beginning with a treaty with the Sultan of Qishn and Socotra) from Aden along the whole coastline from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf, including territory under the sensitive gaze of the Porte, along the Hadhramaut to Muscat.

Diplomacy was not atop Theodore’s list of talents, as his earlier brushes with officials and authorities illustrate. A very injurious comment was made about him in an India Office note of 31 October 1893 that let slip ‘… but they [the Foreign Office] think it right to let us know that, judging by the experience they have had of him, he is neither discreet nor altogether trustworthy.’ (Private note from Sir Arthur Godley to the Earl of Kimberley (31 October 1893; L/PS/3/331/1472/983-85). The note was just one in a flurry of communications between the Foreign and Indian Offices, the Royal Geographical Society, and the British Museum that passed to and fro in the late months of 1893 before the Bents’ expedition could go ahead. Typical of the correspondence was a letter from the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for India to the President of the RGS: ‘In the present disturbed state of Arabia no countenance or assistance should be given by the authorities at Aden to British travellers… [The Turkish government] has repeatedly complained of the presence of Englishmen in the country.’ (Letter of 26 October 1893 from Sir Arthur Godley to Sir Clements Markham (RGS Archives: arRGS/CB7/Bent, T&M)

Against this geopolitical background, Theodore and Mabel consolidated a small mountain of exploratory gear and with a team of assistants and surveyors set out for the Hadhramaut, having circulated a few weeks earlier their customary ‘press release’:

‘Mr. Theodore Bent has almost completed his arrangements for his journey to the Hadramaut country, in Southern Arabia, which he proposes to explore this winter. He starts about the end of next month for Aden, and will then proceed along the coast to Makulla, which is to be his starting point into the interior. The extensive region of Hadramaut is but little known, and Mr. Bent proposes to make as thorough a survey aspossible of the country. He, himself, will pay particular attention to the archæology of the districts, and he will probably be accompanied by a native Indian surveyor, as well as by specialists in botany and zoology. Mr. Bent, who will, as on all his journeys, be accompanied by Mrs. Bent, hopes to be back in England by May or June of next year.’ (The Manchester Guardian, 22 October 1893)

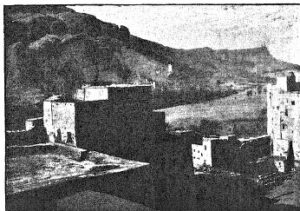

Although ‘Europeans’ had been sailing and exploiting the coastlines of Arabia for hundreds of years, Britain’s need in the early 19th century to make its sea-lanes to India and the Persian Gulf more secure precipitated a brilliant series of coastal surveys that effectively reached from Aden to Muscat. The captains and officers of British vessels wrote and eventually reported back to London on their findings – strategic, botanic, folkloric. Dependence on their ships meant that these men (Mabel was presumably the first willing Western woman to do so) were unable to venture far inland, and it was not until as late as 1843 that the borders of the Hadramaut interior were reached by the German Baron Adolf von Wrede in 1843. As for the great mud-brick cities of the main Wadi Hadramaut itself, they were not visited until 50 years later, and by another German, Leo Hirsch, who, by great coincidence, was covering some of the same trails as the Bents just a few months ahead of them in 1894: therefore ‘to these two parties the credit of the discovery of the Wadi Hadhramaut itself belongs.’ By contrast, western Yemen and the regions to the north-west had been seeing explorers and antiquarians for decades: travellers and scholars such as Halévy, Doughty, Huber, Euting, and Glaser made significant advances in the understanding of ancient inscriptions, on which Theodore was able to develop his research.

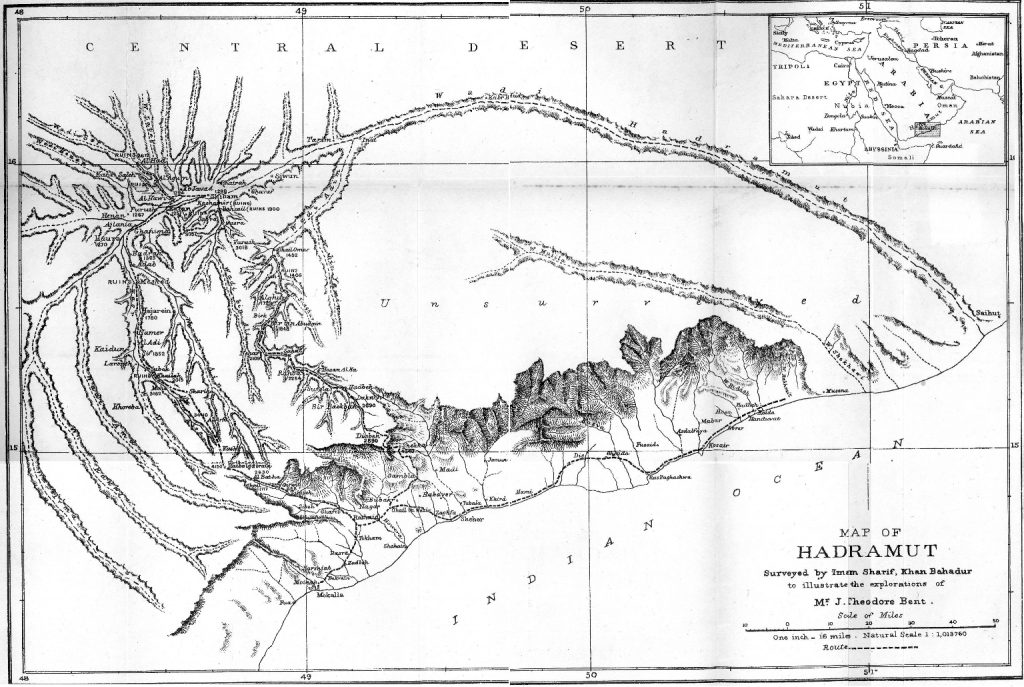

To the expedition’s advantage was the plan for a respected surveyor to accompany Theodore, and the value to Whitehall of an up-to-date map drawn by the Indian cartographer Imam Sheriff (Sharif) was no doubt a powerful contributory factor to their being allowed eventually to proceed. The excellent map drawn by Sheriff, indeed, was perhaps the most valuable item to return with the Bents from a journey that failed to achieve its objectives.

Having arrived in Aden in December 1893, the start to the expedition was inauspicious. Theodore was treated offhandedly for some reason by the Aden authorities, something he and Mabel took for a major slight towards them and the prestigious institutions they represented. There is every chance that academic and political forces were conspiring against him and that the Aden commanders were following instructions. Instead of the substantial help he was anticipating (and no doubt what he felt was due to him and Mabel after his work in Africa), the party received only simple letters of introduction to the sheikhs in Al-Mukalla. This affront is referred to frequently by the Bents and their allies at home.

Immediately Theodore wrote to Scott Keltie at the RGS: ‘Dear Keltie… I cannot make out why it is but I have never in my life been treated by authorities so rudely as I have been at Aden. Col. Stace has unfortunately gone to India and the people here seemed amazed with him for having imported such troublesome people as ourselves. Gen. Jopp absolutely refuses to endorse Stace’s promise of lending rifles and as for the gunboat there is no thought of it and I have to pay £40 to get to Maculla next Friday. All he has done and all he will do is to give us 2 short letters to the Sheikhs of Maculla and Shehr, according to instructions from home. He would not see me for 2 days after our arrival and then in half an hour he managed to be as insolent as he could be. He said “I thought you were coming as a private individual to dig up some Homeric remains and you say you represent certain societies, but we don’t recognize the R.G.S. or Kew or the British Museum here only our own government.”’… (Letter 13 December 1893; RGS Archives: arRGS/CB7/Bent, T&M)

Despite not being given the assistance he was expecting, Theodore assembled the expedition in Aden. In this era of larger scientific explorations, it was the largest party he and Mabel had ever travelled with and the logistical headaches that followed persuaded them that they would not so encumber themselves again. As well as Imam Sheriff and his assistants for mapping, there was also a representative of the British Museum’s Natural History section (later the Natural History Museum) and the young botanist from Kew, William Lunt, for plant collecting.

The Royal Botanic Gardens hold in their archives a fascinating compilation volume relating to the Bents’ Hadhramaut expedition of 1893-94. This includes correspondence, a copy of Lunt’s journal, lists of specimens collected, printed material, and much else. The RBG also hold a number of letters from Mabel and Theodore Bent in their volumes of ‘Directors’ Correspondence’. Their lists of determinations of plants sent to Kew by the Bents are listed in the RBG ‘Plant Determination Lists for Arabia and Nubia’, as well as individual entries for the plants received at Kew in the ‘Goods Inwards’ volumes. Actual specimens collected by Lunt and Bent in the Hadhramaut (and elsewhere) are also held in Kew’s Herbarium. The zoological collections were more limited and the assistant provided by the eminent natural historian Dr John Anderson was inept at times. Nevertheless a collection of specimens, including some creatures ‘new to science’, did eventually reach London (and are now in the Natural History Museum).

Also there to help generally was the Greek dragomános, Manthaios Símos, from the Cycladic island of Anáfi. It is his first appearance in these South Arabian Chronicles but he was an old friend of the Bents, having first met them on Náxos over the winter of 1883-4. Manthaios travelled with the Bents on their journeys to Greece and Turkey, but did not accompany them to Bahrain and Persia. Now however he is persuaded to leave the Cyclades and act as general factotum for Theodore and Mabel once more. He was, of course, paid, receiving the equivalent in today’s terms of about £5000 for the season. Such occupation was relatively common for enterprising men from remoter communities and Manthaios (who apparently had a tobacco shop of some sort on the island) was later able to ‘retire’ to Athens with his young family and where his descendants still live in 2010. He is encountered again in Mabel’s diaries for 1897, when he plays a part in saving her life on the couple’s final journey together.

On this trip, as before, Theodore was a keen sketcher and Mabel took the role of expedition photographer, carrying with her all the materials and equipment she would need for developing in the field. Her Hadhramaut Chronicle contains frequent accounts of the difficulties she faced as a pioneering photographer. Unfortunately only a very few of her images have survived. Some feature in Southern Arabia and Theodore’s monographs and articles. Others existed in the form of presentation slides that Mabel prepared for her husband’s lectures (alas many of Mabel’s RGS slides were thrown away in the 1950s on account of their poor condition).

Once home in London Theodore was soon speaking to the RGS (and still obviously furious with the lack of respect shown to him in Aden), his account being much praised after his talk: ‘It remains for me to express your thanks to Mr. Theodore Bent for his admirable paper and his sketches, and to Mrs. Theodore Bent for her photographs, which together have given us a very clear idea of the country which was almost, if not quite, unknown to us… You will agree that they have done their work in a most admirable way, and brought back to us descriptions of a most romantic country of which we have only before heard rumours… in the absence of official help, which they had a right to expect from Aden, most improperly withheld from them.’ (The RGS President in ‘Expedition to the Hadramut: Discussion’, 1894, 331–3).

Theodore also exhibited some of his small assemblage of archaeological finds at his lectures, before some were acquired by the British Museum – where they join his other finds from the eastern Mediterranean and Africa, and include some of the items illustrated in Southern Arabia. D. G. Hogarth, spy, and Bent enemy suspect number one, won’t resist a dig: ‘The gleanings of inscriptions brought back by Wrede, Hirsch, and Bent are meagre beside the harvest reaped by Glaser in Marib alone…Townsmen do not yield the secret possessions of their houses to the first comer, be he even as expert in their speech as Hirsch, much less to one, like Bent, communicating in halting Arabic or through interpreters.’ (‘The Penetration of Arabia, 1904, London, p. 223)

Of all their acquisitions from the Hadhramaut, the most intriguing object remains a now (suspiciously) lost, small clay stamp, a seemingly exact copy of one that was found later during excavations in Bethel, north of Jerusalem. Some years after Theodore’s death, Mable wandered, confused and alone, in this same area of modern Israel and rumours have appeared in print that she placed the stamp in Bethel as a memorial of some sort to her husband – a memorial to Theodore’s theories of a trade route (especially in frankincense) running from the Hadhramaut, north-east to the Holy Land. Archaeologists and others have convinced themselves for, and against, this legend.

Notwithstanding the truly remarkable feat of endurance itself, it was in Theodore’s interest back in London to put as good a ‘spin’ on his discoveries in the Hadhramaut as he could – his reputation (and future funding) depended on his results. Even though he would evidently not have been prepared to commit himself to lengthy excavations in the desert, and was satisfied to make a gradual assemblage of evidence that could be worked up later into a monograph on the early kingdoms of the Arabian peninsular, the actual material (in all disciplines) he returned with was a disappointment.

Although Theodore put as good a gloss as he could on the achievements, he failed to reach either Shabwa to the west or to the eastern extremity of the Wadi Hadhramaut (Wadi Masila) on the Indian Ocean at Sayhut. The party had to curtail their mission and settle for a shorter descent to the coast again at Sheher (Ash-Shihr). Freya Stark, who was in the region forty years later, made sure she was not going to repeat the couple’s mistakes (Seen in the Hadhramaut, 1938):

‘The Bents had many troubles, due chiefly, I think, to their imperfect knowledge of the language and to the fact that they travelled in opulence at a time when the hand of government was far too weak and distant to impress the beduin tribes.’

But let’s end with three strong references to the Bents’ achievements in the region:

‘As the country has been gradually opened up, a number of women have been seen in the interior. Mrs. Bent was the pioneer. No other woman visited the interior until recent years.’ (Ingrams, W.H. (1938). ‘The Exploration of the Aden Protectorate’. The Geographical Review, Vol. 28 (4), 638-51)

‘Undaunted by the experiences of her late tour through Abyssinia, Mrs. Bent… is busily engaged preparing for one of the most important journeys yet undertaken by her, for Mr. Bent has chosen South Arabia as the scene of his next explorations, and, as usual, his wife will accompany him… Leaving London in November, Mr. and Mrs. Bent hope, if all goes well, to remain in Arabia until March or April, 1894, when they will return direct to England, as the intense heat which sets in about that time makes it necessary for the inhabitants of northern latitudes to leave so enervating a climate.’ (Hearth and Home, 2 November 1893)

‘Theodore Bent will always be remembered as the second European traveller, and the first Englishman, who ever got into the main Hadhramut valley.’ (Review in Man, Vol. 1, 1901, 29–30)

Mabel’s Chronicles and Theodore’s own notebooks of this journey formed the nucleus of the relevant chapters in their monograph Southern Arabia, written up by Mabel for publication in 1900, three years after Theodore’s death. Her first Hadhramaut notebook includes the party’s preparations in Aden (December 1893) and subsequent sea voyage to Al-Makulla. Mabel then details their slow progress to Al-Khotton, which becomes their base for a month while they try to arrange guides to take them into the Wadi Masila and the south coast again at Sayhut. When this fails, she chronicles their shorter journey to the port of Sheher (Ash-Shihr) (March 1894).

The second notebook (‘Hadramaut – no 2. A 1894’) completed by Mabel continues (March 1894) with a short exploration east along the coast to Kossair before returning to Sheher (Ash-Shihr), from where they take ship, via Al-Makulla, for Aden once more (end March 1894) and the long journey home (20 April 1894).

Amongst all Mabel’s notebooks in the archives of the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies, London, a strong case can be made for these two slim volumes being the most valuable.

In a review of Bent’s monograph The Sacred City of the Ethiopians (1893), the Anglo-American Times of Saturday, 24 March 1894 writes: “Another expedition was conducted in Southern Arabia to explore Hadramant [sic], and after working among its antiquities Mr. Bent will follow with another volume. Although the Arabs expected and hospitably entertained the party, on four occasions it was fired at by watchers in the towers that guard every little patch of territory. It is not known what the archaeological results of the expedition have been, but it will be remembered that Mr Bent aimed at connecting his Hadramant [sic] researches with those previously made at Aksum, in Abyssinia, and at the Zimbabwe, in Mashonaland.” Particularly interesting is the early reference to a book on Southern Arabia, which was not completed at the time of Bent’s death in 1897 and appeared finally (and famously) in 1900, completed by Mabel. Also noteworthy is the perspicacious end comment on Bent’s intention to find a research synthesis, linking his work in the last decade of his life and outreaching his results from the previous decade spent (with Mabel of course) in the Eastern Mediterranean.