Our recent post (May, 2020) of an article by Jennifer Barclay (Wild Abandon: A Journey to the Deserted Places of the Dodecanese, Bradt Travel Guides, 2020), in which Jen says how she finds the Bents, generated a fair bit of interest. A series of posts by other well-known travel writers (if this could be you, write to us), who were guided by Theodore and Mabel, will therefore follow, as and when…

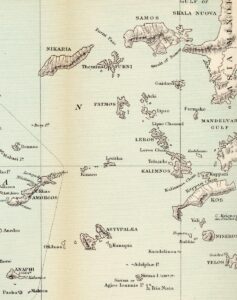

Marc Dubin (Rough Guides and much else for decades) was kind enough to write a preface for Bent’s second Greek island book (The Dodecanese: Further Travels Among the Insular Greeks, 2015) and this can now appear online – at a time when hopping around the Cyclades and Dodecanese, for British tourists at least, is all but impossible this summer (2020).

Marc, a long-term resident of Samos, is a favourite of ours; actually more than that, because it was his inclusion of a reference to Bent’s The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks (1885) in a Rough Guide bibliography that led circuitously, a kalderimi stumbled upon, right to the Bent Archive’s front door, some 30 years later. Here is what he has to say about the Bents; and thank you Marc.

Marc, a long-term resident of Samos, is a favourite of ours; actually more than that, because it was his inclusion of a reference to Bent’s The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks (1885) in a Rough Guide bibliography that led circuitously, a kalderimi stumbled upon, right to the Bent Archive’s front door, some 30 years later. Here is what he has to say about the Bents; and thank you Marc.

“I have been writing about the Greek islands since 1981, and the Bents have accompanied me from the start. After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1977, I stayed around town for some years; I was fortunate in having a part-time job at the university library which was piecework based and allowed me to work full-time for three months and then take equal time off to travel. It also gave me complete, unchallenged run of the book stacks, where I furthered my education through omnivorous reading. There was no security whatsoever at the employees’ entrance, so books could be ‘borrowed’ indefinitely.

The pre-computerisation card catalogue listed no less than four copies of J. Theodore Bent’s Aegean Islands: The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks, published as a 1966 reprint by Argonaut in Chicago. I had just signed my first contract to write a guidebook on Greece. Why should the library keep four copies of this title, when my research needs were greater? Home it went, to stay, in 1980.

James Theodore and Mabel spent nearly a year travelling around the Aegean on their first trip, back when it took a year to visit all the islands given the vagaries of the wind – as he writes in the volume you are holding, ‘those who go to Astypalæa must be people of a patient disposition’. They more (or less) cheerfully tolerated ferocious winter weather, leaking quarters, foul-smelling wooden boats, monotonous food (‘pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold, pease porridge in the pot nine days old’ was literally and repeatedly enacted), rapacious boatmen and voracious vermin. They took shelter in bare churches when necessary, something sadly unlikely now when so many rural chapels are locked against theft or desecration. It all puts today’s island-traveller whinges about cancelled sailings, greasy food and wonky water heaters in stark perspective. To their immense credit, the Bents were keenly interested in the contemporary Greek islanders, not just in antiquities, unlike 18th-century Grand Tourists who disparaged the supposedly degenerated medieval Greeks and modern tourists who are only after sun, sea and sex.

The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks, also available through Archaeopress, has the dubious honour of being the most plagiarized book ever written on the Greek islands – almost every 1960s to 1980s writer on the Aegean helped themselves to entire pages worth of Bent, verbatim. It was legally if not ethically okay to do so, since the text (as the Argonaut publisher told me when I asked him) had long since been in the public domain; the Bents had died without issue or any other heirs to extend the copyright. Copyright aside, it’s easy to see why this happened: the intrepid Bents had been there, and done that, long before there were any t-shirts, and what they had observed and documented was far more compelling than anything actually visible on the islands from the 1960s onwards. Bent had also described their sojourns in brisk, to-the-point prose; it’s hard not to warm to someone who could write ‘on my remarking that I should prefer an inside place [on a raised communal family bed] for fear of a fall, they laughed and told stories of a sponge fisherman who dreamt that he was going to take a dive into the sea, and found himself on the floor instead; and of a priest, who rolled out of bed when drunk and broke his neck…in inferior establishments the space beneath the bed is used as a storeroom for all imaginable filth’.

On my extended 1981 trips to Greece, I had to quell lurking disappointment that the islanders were no longer as Bent described them. Or not quite anyway; on Sífnos my young hostess told me that there was still an old woman alive locally who could ‘draw out the sun’ from those afflicted with sunstroke-headache by sleight of handkerchief and incantations, exactly as described in Bent’s Kímolos account from 1883. Later a much older friend told me how, serving as a British delegate to the United Nations Special Commission on the Balkans (UNSCOB), monitoring border violations during the Greek civil war, he had – despite his total disbelief in the rite – the effects of the Evil Eye exorcised, again through spells and fabric manipulations, by an old Sifnian man, Nikos, in 1948, in Macedonia.

But one can hardly expect such customs and costumes to have survived decades of emigration, electrification, radio and gramophones, public schooling whether Italian or Greek, meddling foreigners and government policy. Bent himself took a dim view of his own countrymen abroad: ‘It is the Union Jack which scatters [quaint costumes and still quainter customs] to the winds: great though our love is for antiquity, we English have dealt more harshly than any other people with the fashions of the old world.’ During the mid-1960s, even before the culturally destructive colonels’ junta, Kevin Andrews observed how local police felt it necessary to ban the playing of bagpipes at Mykonos port lest ‘foreigners…think us Mau-Mau’. You wonder what the Bents would make of today’s mercenary anthropological zoo centred on the village of Ólymbos in northern Kárpathos, which I first decried in my own 1996 guide to the Dodecanese and North Aegean. Research for that first edition involved criss-crossing the archipelago for several consecutive seasons in just about every month of the year (barring February and March) and every conceivable seagoing conveyance. Perhaps my most Bent-ian experience was in that self-same Ólymbos, when a nistísima meal (compliant with the Lenten fast) turned out to be simply limpets and myrouátana, a delicious seaweed which I have never been served again despite asking repeatedly.

During the late 1980s, in Moe’s – that Berkeley shrine of used books on Telegraph Avenue – I found another copy of the Argonaut Press edition of Aegean Islands, in mint condition, for the paltry price of $7 US: a fair measure of the scant esteem then in the USA for the Bents and their writings. The same copy in Britain at that time fetched at least thirty quid. Even now, antiquarian bookselling websites do not much value this handsome original reprint.

Shortly afterwards – I had not yet left the US to settle in Britain and Greece – I retrieved the purloined copy from my own shelves and headed for my old haunt, the UC Berkeley library. Back then (and probably still now) you could return a book in perfect anonymity, which I did eight years after its initial ‘check-out’, using the large-mouthed chutes near the main doors. It is not a small book in any sense, especially the old cloth-cover edition which is by my desk as I write, and made a satisfying clunk as it hit the bottom. So there should be once again four copies of Aegean Islands in the library’s holdings.

© Marc Dubin Áno Vathý, Sámos, December 2014

Bent’s The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks is freely available online, or as a printed version via Archaeopress, Oxford, or your usual book provider . Get travelling with the Bents…

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article