“Mr. Theodore Bent, the famous archaeologist is going to explore the island of Sokotra, on the West Coast [sic] of Africa, this winter. Sokotra is said to contain some important ruins, and if Mr. Bent can discover anything as interesting as the buried cities of Mashonaland he will have again achieved fame.” (‘The Morning Leader’ – Tuesday 08 December 1896)

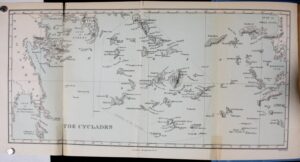

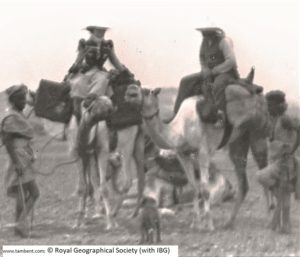

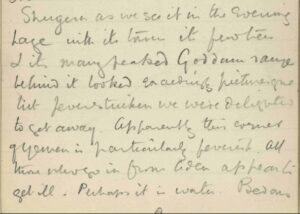

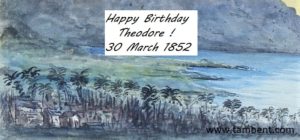

Poor Theodore Bent spent his 45th, and last, birthday (30 March 1897) in hospital in Aden, malaria stricken. Just a few weeks beforehand, however, he and his wife Mabel were happily wandering on camels through the plains and mountains of Socotra – a speck a centimetre west of the Horn of Africa on most maps – looking for archaeological remains and enjoying the fantastical scenery; Mabel took photographs while Theodore sketched in watercolour in his naïve way. How far back did he work at this style? As a Yorkshire Baildon boy? Or at Repton and Wadham? In any event he obviously took pleasure in the art and his illustrations later assisted his studies in the field (reminiscences, maps, plans, inscriptions, etc.); he felt assured enough to have his views published in all his books and, editors permitting, in many of his articles that had to do with the couple’s adventures in the Eastern Mediterranean, Ethiopia, Great Zimbabwe, Southern Arabia, Persia…

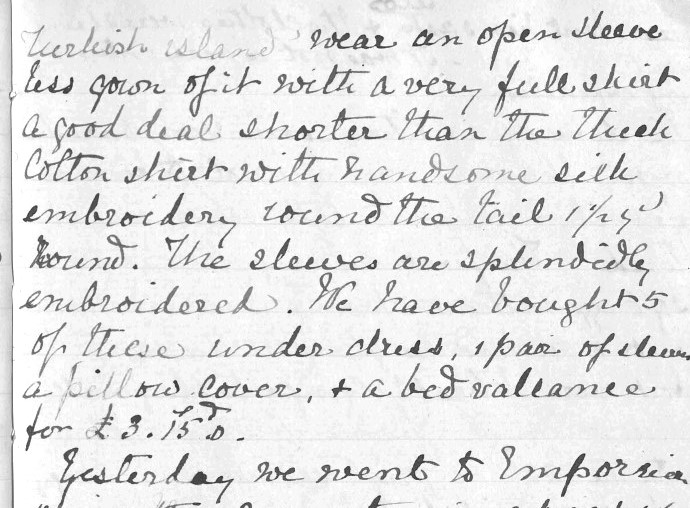

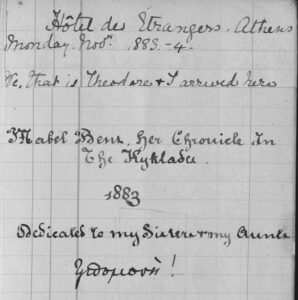

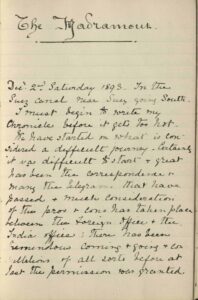

Mabel’s diaries often refer to her husband’s drawing materials and sketches, calling the latter ‘pretty’. Theodore was sketching on his last trip, in 1897, to Socotra and Aden, as his wife records: “[Thursday] February 4th [1897]. The mountains of the Haghier range [Socotra] are most beautifully peaked and needled, and here look red, not being smothered by the smooth, grey lichen. We were, though sorry to quit the mountains, glad to reach the plain, cross a river on stones and mount our camels and reach Suk… We encamped by a lagoon and had a pleasant afternoon and evening walking by the sea, and also choosing places for photography on the morrow and Theodore sketching. We had to keep the tent open at night it was so warm and still.’ [‘Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent’, Vol. 3, Southern Arabia, 2010, page 303]

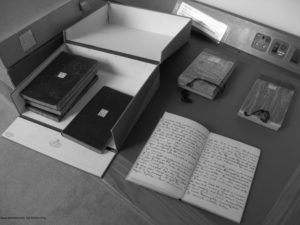

Several of Bent’s watercolours of Socotra are illustrated in the couple’s great work ‘Southern Arabia’. His sketch book (17.5 x 25 cm) obviously survived the rigours and maladies of the hard journey and return home from Aden at the end of April 1887. Although Theodore and Mabel were still terribly ill, once out of hospital, and barely fit for travel, they embarked immediately for Marseilles. There Theodore had a relapse and although rushed back to their London home, he died a few days later in early May (1897). His sketch book remained unopened until Mabel felt strong enough psychologically to have the watercolours photographed and prepared as plates for ‘Southern Arabia’, the anthology of their years spent in the region.

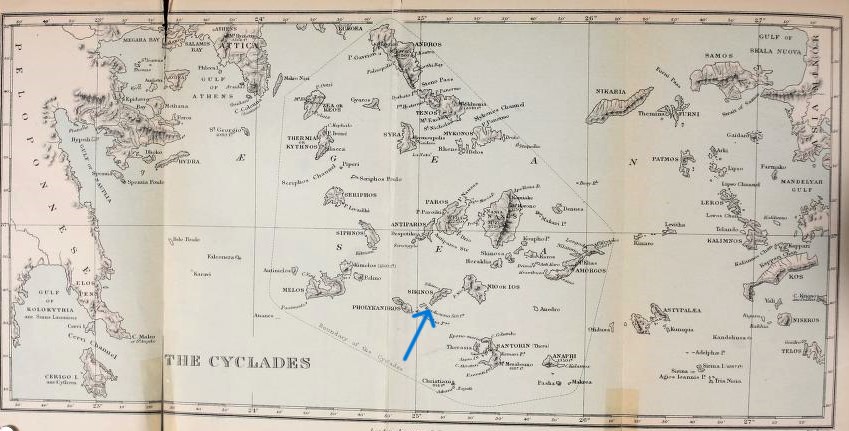

As for the original watercolours now, who knows? But by a miracle, one has survived in a private collection – it probably never travelled back to Marble Arch with the invalid couple in the spring of 1897: it is a scene of ‘Kalenzia’ (Qalansiyah), a coastal village at the extreme east of Socotra (a Google image of the area is also shown here below); we are looking west, it is sunset, the mountains above the village sombre; in the foreground, among palm trees, are a few simple huts and what looks like a mosque with its minaret. Theodore has signed his name bottom right, with the inscription ‘Kalenzia, I[sle] of Socotra, 1897’.

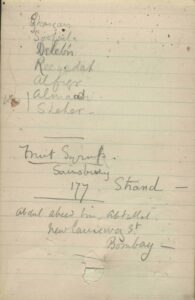

The DNB of 1901 adds to Bent’s entry that “[his] notebooks and numerous drawings and sketches remain in the possession of Mrs. Bent.” A few of his notebooks are in the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies, London, but where are his “numerous drawings and sketches”? Do please let us know if you have any information on Theodore’s unpublished ones!

Let’s be clear, although Theodore made hundreds of them, surviving original watercolours by him are as rare as evidence of the elusive Queen of Sheba he spent his last years looking for. A portfolio of watercolours of Great Zimbabwe and its surroundings is thought to be in Harare… and that’s it, apart from the aforementioned scene of ‘Kalenzia’, a detail of which is appropriately used for Theodore’s last birthday card (heading this post). This mesmeric scene is not reproduced in the Bents’ ‘Southern Arabia’, but it would surely have if Mabel had been in possession of it as she worked assembling her book in London in 1900. As mentioned previously, the chances are the picture never reached Marble Arch with the rest of their travel gear in the early summer of 1897. Did Theodore give or sell it in Aden, or on the long journey home by steamer, through Suez, to Marseilles. Did someone say, ‘That’s nice’, and Theodore present it with a bow – perhaps to Henry Watts Russell de Coëtlogon (1839–1908), with whom the Bents dined in Aden on their last, sad, journey? It surely could not just have been lost (or stolen) before the Bents reached England? The happy coda is that, whatever happened to it since it materialised in Qalansiyah some 120 years ago, it appeared at auction in Germany in 2013, selling for 100 Euros, and is now, presumably, being privately and luckily enjoyed; if by you, please let us know. Happy birthday Theodore.

Socotra is of universal importance with a biodiversity of rich and distinct flora and fauna, much of which does not occur anywhere else in the world. It also has globally significant populations of land and sea birds, including a number of threatened species and an extremely diverse marine life

In order to raise awareness of the rich and distinct heritage of Socotra, UNESCO is collaborating with the Friends of Socotra in organising a campaign of awareness events and publicity around the world. Using the hashtag #connect2socotra, the purpose of the Connect 2 Socotra Campaign is to connect the world to Socotra, and connect Socotra to the world. Search Google for campaign news and events.

December 2022 – a new discovery: A further unpublished watercolour sketch by Bent made on Sokotra in early 1897, showing two camels and distant mountains, appears in Alice Norton: ‘Mabel Virginia Anna Bent – Explorer’, appearing in Carloviana 2023, the Journal of the Carlow Historical and Archaeological Society (Dec. 2022, pp.117-123).

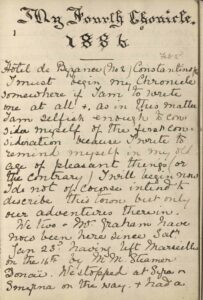

A review of Bent birthdays based on Mabel Bent’s Chronicles, 1884-1897

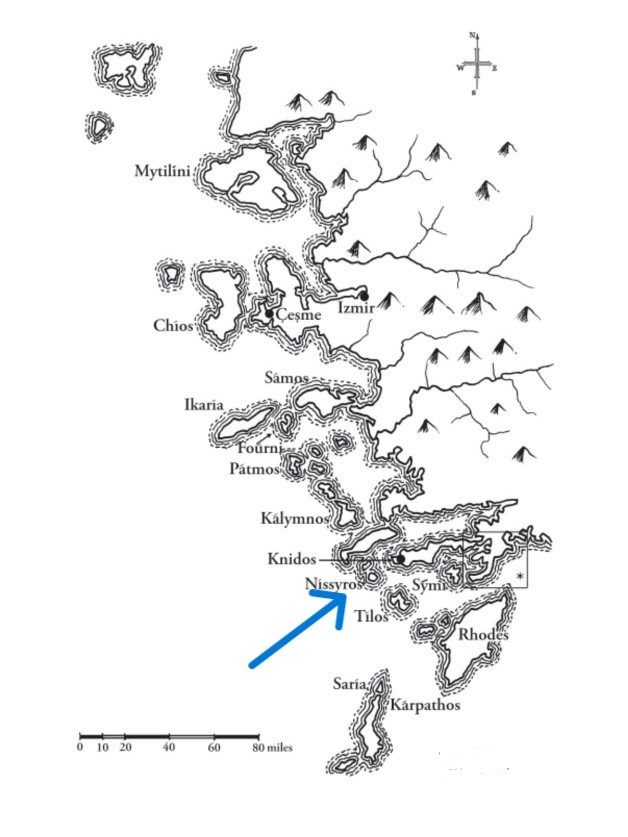

The accompanying interactive map below plots these birthdays: Mabel in green, Theodore in blue. (NB: London [13 Great Cumberland Place] stands in for unknown locations in Great Britain; the couple could have been away visiting family and friends in Ireland or England, including at their property ‘Sutton Hall’, outside of Macclesfield.)

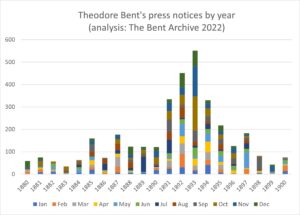

There were 28 Bent birthday events (2 x 14) between 1884–1897 (the years covered by Mabel Bent’s diaries). Of these 28, only 5 (18%) were not spent in the field, and only 7 times (25%) does Mabel refer to a birthday in her notebooks directly. In the above Table, column 1 gives the year and ages of the Bents on their birthdays; columns 2 and 3 give their birthday locations. Events in red are when Mabel refers directly to their birthdays. ‘London’ is standing in for unknown locations in Great Britain. If not at their main residence (13 Great Cumberland Place), the couple could have been visiting family and friends in Ireland and England, including at their property Sutton Hall, outside of Macclesfield.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article