Theodore and Mabel Bent in Ethiopia/Aksum: January – March 1893

“Forthwith my husband began trying to dry squeeze inscriptions in the condition of wet blotting paper, trying to get them in the sun and shelter them from the wind. I frizzled some negatives trying to dry them on the teapot, as I dared not go out in the sun for fear of dust, and our servant made himself wretched over some delightful and valuable dripping which would not cool. Meanwhile we packed our boxes keeping one open for these treasures, the mules being ready at the door waiting for the last possible moment.” (‘The Monoliths of Aksum’ (Mrs. Mabel V.A. Bent), Records of the Past, 1903, Vol.III, Part II, February, pp. 34-42)

In London once more, via Lisbon, from Mashonaland and South Africa, in early February 1892, Theodore was a minor celebrity. He had come home with crates of finds from ‘Great Zimbabwe’ and a theory that no one for the moment could gainsay about prehistoric southern Arabian influence, trade and power – exotic Sabaeans, or Minyans or Himyarites, using the coastal sites of what is now Mozambique, to transport from their bases in central Africa to their cities in the southern Arabian peninsular shiploads of gold, ivory, spices, and slaves.

The Western Morning News of Monday 4 January 1892, greets the passengers at Plymouth disembarking from “the steamship Norham Castle, which arrived … on Saturday from the Cape. Mr. Theodore Bent, the explorer of the ancient cities in South Africa was a passenger to Madeira. From that island he proceeds to Lisbon with the view of consulting the ancient records of Portugal in connection with South Africa.” (Although there seems to be a little confusion as to the vessel! Mabel in her diary says they are to take the Norham, but Theodore in a letter to the Times refers to her sister ship, the Doune Castle. In any event, the Bents were delayed at Madeira for some days in early January 1892 before changing ship for Lisbon, where Bent went to consult some archives. The couple finally returned to London at the end of January and Bent immediately went to work preparing his papers to present to the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association, two of his sponsors.)

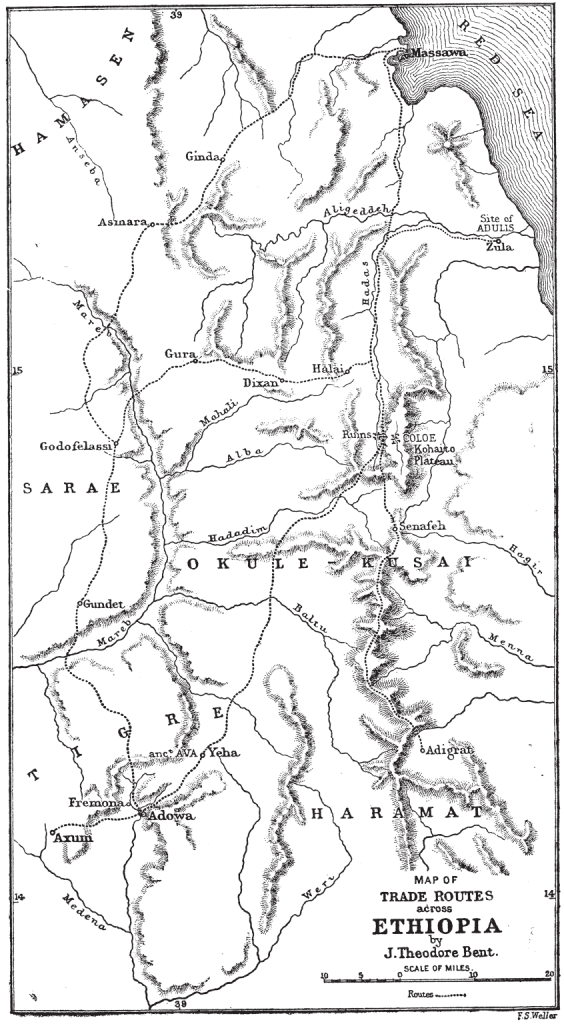

Research by Theodore in London and in the Lisbon archives, and correspondence on inscriptions and possible architectural similarities between features in Mashonaland and Marib (Yemen), introduced Theodore to the little-explored interior of Ethiopia, and its evocative ‘capital’ Aksum (Axum), about which a slight but resonant body of evidence had been assembling for several decades pointing to the possibility of links between early trading networks and cultures comprising both east and west shores of the Red Sea.

Having decided on his field of research for his 1893 season Bent had the usual preparations to see to. There would be no funding this time from Cecil Rhodes but Theodore secured financial support from the British Museum (in return for any artefacts), the RGS, and the British Association (particularly the Anthropological Section.

To contribute towards the costs Theodore let it be known that the expeditionary party would be amenable to the company of ‘a scientific man’:

‘Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent have arranged to spend the winter in Abyssinia studying the ancient monuments of Axum. They will leave this country about the middle of December. We understand that Mr. Bent would welcome a scientific man who might wish to work at any of the natural conditions of eastern Abyssinia, and take advantage of the arrangements which have been made for the safety and comfort of the party. It would, of course, be necessary for such a companion to pay for his own expenses and provide his own outfit.’

Luckily, as it turned out, for the ‘scientific man’ there were no volunteers on this occasion. The Bents’ Ethiopian expedition of 1893 was their last not to provide facilities of one sort or another for the gathering of floral and faunal specimens or data, necessitating additional materials and transport as a result. There was, however, an indispensible member of the team still to summon. The Bents will have wired, via no doubt the Telegraph station on Sýros in the Cyclades, to their Greek assistant Manthaios to pack and make ship for Port Said. ‘As good as ever and as great a comfort’ – so Mabel writes in her letter of 17 March 1893 – Manthaios Símos (c. 1845 – c. 1935) served the Bents for fifteen years, having first set eyes on him in a smoke-filled Náxos room in January 1884.

Nearing the departure date, and the waiting trains and boats for Dover, Calais, Marseilles and Suez, Theodore attended as usual to his press releases:

‘Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent have started for ‘Abyssinia’, where, under the protection of the Italian Government, they hope to do some work at the ruins of Axume [sic], the ancient capital of the old Ethiopian kingdom; and after staying there some time and thoroughly examining the neighbourhood, they hope to get as far as Gonda.’

If the couple were hoping for a stable geo-political situation on arrival at the Italian sea-base of ‘Massowa’ early in January 1893 they were to be disappointed. In a letter to the RGS (19 February) Theodore confides: ‘In fact at that time it looked almost hopeless, and we nearly decided to go off to Suakim, but the Governor encouraged us to wait a few weeks’. Thus, and not for the first time, the expedition soon found itself in some physical danger – caught between the new Italian colony’s efforts to establish itself and the brewing unrest between the warlords of Ethiopian Emperor, Menelik II. As dangerous then as now, the Bents could hardly expect a British rescue force to ride to their aid.

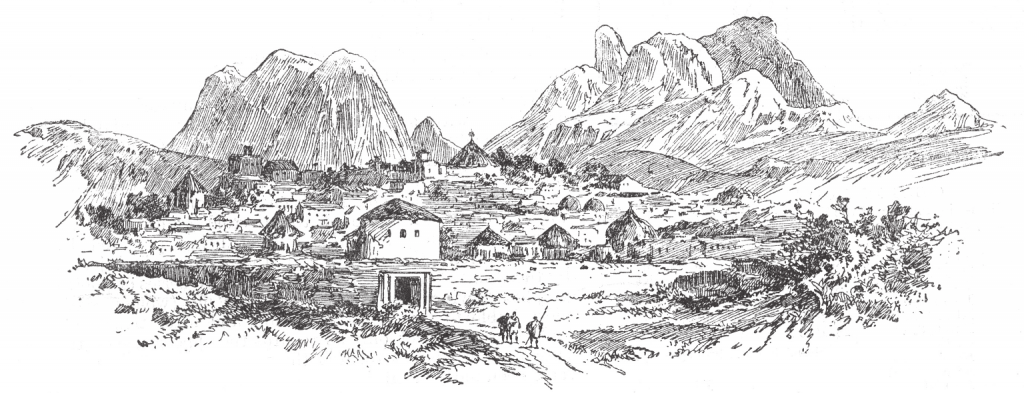

With protracted investigations at Aksum their goal, the Bent party proceeded at a slow pace to Asmara from the coast to await an understanding from the various Ethiopian authorities that it was safe for them to travel on to Adwa and beyond. They were held up at Asmara long enough for them to make a detour north to Keren, but were eventually allowed on to Adwa (in communication the while with the major figures on the Italian and Ethiopian sides, who were slowly manoeuvring in a deadly trajectory towards a devastating – for the Italians – defeat outside Adwa on 1 March 1896.

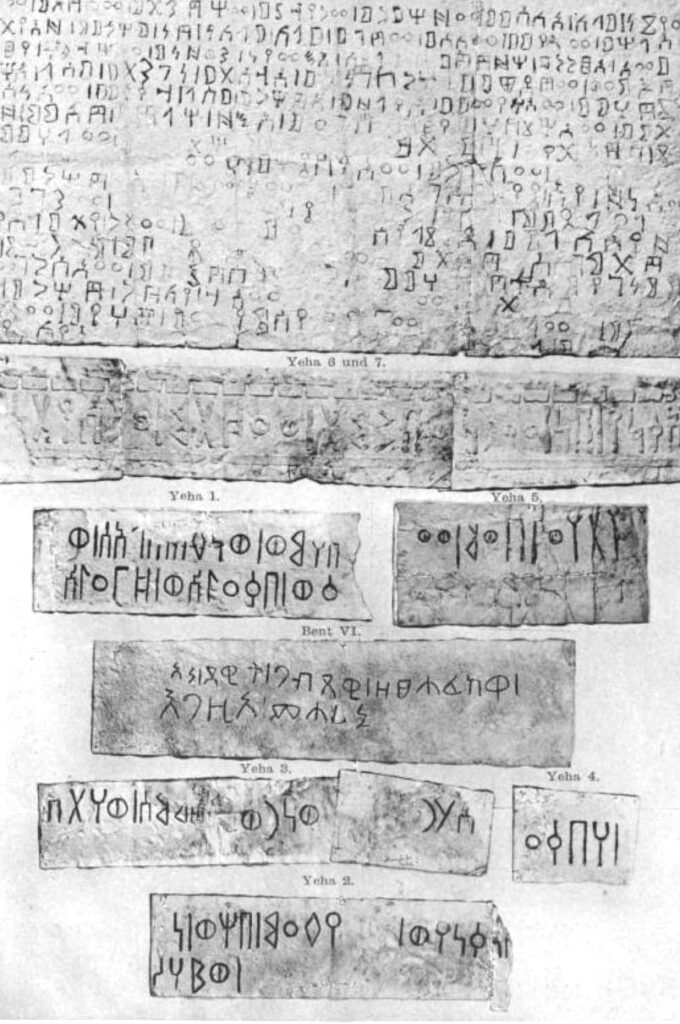

But the massacre at Adwa is three years away and the Bents make the most of their stay there in February 1893, despite uncertainty about the rest of the trip. Never ones to be idle Theodore and Mabel ride out five hours to the village of Yeha. Here Theodore makes one of his two major contributions to the archaeology of the region by associating a known ruined structure with an early temple, and the site itself with ancient Ava. He also took copies (‘squeezes’) of a number of key inscriptions. Although unclear in his interpretations his work on the site still features in the bibliographies of modern theorists who wrestle for an understanding of the various Aksumite and Pre-Aksumite cultures in the first and second millennia BCE and associations with peoples of the time on the opposite coast of the Red Sea to the east, and the Nile region to the west.

From the start, these inscriptions raised interest and debate among the great names of the time, especially Eduard Glaser and David Müller, both of whom became involved with Theodore’s squeezes from Yeha and Aksum, disputing both text and context with some venom. Bent first came into contact with Glaser in 1892, asking the latter for his thoughts on the ‘inscription’ he, Bent, had acquired at Great Zimbabwe the previous year. Glaser alludes to Muller as his ‘arch enemy’ and is suspicious that Theodore is secretly representing British colonial interests:

‘The Englishman Theodore Bent, who has for several years travelled with his wife in the countries surrounding the English colonies… to knit up friendly relations with the chiefs… after having visited Mashonaland, since become English, went on to East Africa, and… turned his eyes on Abyssinia… [where] he rejoiced in the kindest and most willing support of the Italian government, but arrived just at the moment when an Anglo-Italian entente for the reconquest of the Sudan was spoken of.’

Subsequently Müller published Bent’s squeezes in his arcane Epigraphische Denkmäler aus Abessinien Nach Abklatschen von J. Theodore Bent, Esq. (Vienna, 1894). It is a unique record in that it includes reproductions of a few of Bent’s actual squeezes – now presumed lost. (Bent was a prolific taker of squeezes in the Levant, Africa, and Southern Arabia. At least one has survived, i.e. that of the notorious ‘Bethel Seal‘, held in Glaser’s collection (A727), Vienna.)

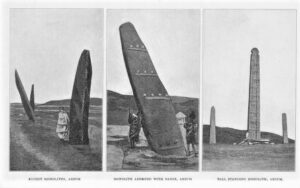

Eventually the Bent expedition was allowed to continue to Aksum, the intended focus of Theodore’s research. His work there was curtailed by factional tensions, and although he did find some previously unpublished inscriptions, his accounts of the famous monoliths and other antiquities of the country were by then familiar to European specialists. Thus the Bents had to cut short their work at Aksum and retreat back to the coast, via the central plateau north of Senafe. Theodore managed to write to Scott Keltie at the RGS on 7 March 1893:

‘We have just got back to Italian territory again after having had a very anxious and dangerous sequel to our Abyssinian experiences… We passed eight days at Aksum, with great profit, I hope, to ourselves and archæology, for though under the circumstances it was impossible to do any excavation, we found plenty of work amongst inscriptions, obelisks, &c., to keep us well employed for that time – taking squeezes, photos, measurements, &c. We then got intimation from the Italian Resident at Adua to depart immediately; that the war was assuming alarming proportions; that the north of Tigre was infested by bands of brigands; and that our ultimate retreat out of the country was very doubtful… The road being infested with brigands, it seemed as if we were caught in a trap… We passed two very anxious days, not knowing what was going to happen to us… [This is] quite the most unpleasant experience we have had during any of our travels, and I need hardly say we are enjoying a few days of rest and tranquillity here immensely. I think, in spite of our difficulties, we have done some good and important work at Aksum. We shall probably go on to Aden in a fortnight’s time, and get back to England earlier than we expected.’

Theodore’s remark that the incident was ‘quite the most unpleasant experience we have had during any of our travels’ (although they experience similar difficulties in the Wadi Hadramaut the following year) was British understatement – they could all easily have been captured, with little hope of rescue (and see Mabel’s anxious letter home).

Back on the coast, Theodore and Mabel visit the well-known remains near Zula of ancient Adulis, some 60km south of Massowa, and findspot of a famous inscription by Henry Salt in the early 19th century. Bent was well aware of the site from references in Greco-Roman literature, and into modern times. Still not fully explored Adulis remains fascinating in terms of any understanding of the early development of the wider region (including commercial activities generally in the Red Sea) from the mid-first millennium BCE to the Islamic period of the seventh century. However the Bents were unprepared for protracted digging at the site – they spent one night there and had no time to excavate.

It was time, March 1893, for the Bents to return to Massowa and pack for England. As usual, the couple were carting interesting items to bring home – either as souvenirs, or at the request of museums, or for their personal disposal at a later date. The Yeha inscriptions could not physically be removed, but the Bents (as the illustrations in The Sacred City of the Ethiopians bear witness) did manage to obtain a not particularly precious collection of religious artefacts, musical instruments, ornaments and clothing; perhaps the prize acquisition was the naïve painting of the Crucifixion now in the British Museum.

Theodore began his written commentary on their Ethiopian expedition as they were travelling. He wrote letters to his contacts at the RGS, and directly to the Illustrated London News, sending them two articles, one of which was published in two parts over consecutive weeks, including his own drawings. It was to his book, The Sacred City of the Ethiopians, that Theodore devoted the summer of 1883, and by Christmas it was published. The reviews were many and generous, with special note being taken of the author’s illustrations and Mabel’s efforts as expedition photographer, especially the monuments from Axum.

Theodore never returned to ‘Abyssinia’ but it was his first-hand experience of the monuments of the Aksum region, following directly on from his investigations at ‘Great Zimbabwe’, that fired his imagination about possible early contacts spreading outwards from Southern Arabia, from the wadis of the Yemen and, particular, the wastes of the Hadramaut.

Postscript (December 2020): It’s no secret that the BBC’s World Service is full of secrets – waiting for adventurers to discover: adventurers like Theodore Bent. Currently (December 2020) in its treasure of a series , ‘The Forum’, there is an episode on the enigmatic stelae of Aksum (see above – erstwhile capital of an Abyssinian region dated to some 2000 years ago, and frantically explored by Bent and his wife in 1893). The fact that the Bents are not referenced, however, is a serious academic omission (modern archaeologists are still condescending towards them), especially since the nearby and important site of Yeha was first identified by Bent. The episode refers to Aksum’s ‘stele 2’, removed by Mussolini for Rome in the manner of former despots and now happily returned, but not that it was actually photographed some 50 years earlier in situ by Mabel Bent and reproduced in their most readable adventure – ‘The Sacred City of the Ethiopians’. Despite this, the programme (with contributions by Helina Solomon Woldekiros and Felege-Selam Solomon Yirga and Niall Finneran) is a must, as is the Bents’ account.