Our recent post (13 Oct 2020) on the hundreds of items in the British Museum collected by Theodore and Mabel Bent, was ultimately about things – their contexts, consequences, associations, the meanings of value…

It will probably come as no surprise that Mabel Bent’s paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Hall Dare (née Grafton, 1793-1858), also had a great many things (the wider family units being landowners in Essex and with interests in the sugar plantations of British Guyana)… including, it seems, a towel, a drinking-horn, a bell, a thermometer, and, oh yes, a quantity of butter, two and half pounds in weight in actual fact.

Oddly, let’s move at this point to that lowering fortress of justice, the Old Bailey in London in 1840, as recorded in The Weekly Dispatch (page 507) of Sunday, 25 October, with reference to a petty case that was tried on the 19th of that month and year.

We read in the said tabloid, obiter dicta: “Christopher Johann Frederick Auguste Struve, described as a dealer, was… indicted for burglariously entering the dwelling house of Mrs. Elizabeth Hall Dare, and stealing therefrom a towel, a drinking-horn, a bell, a quantity of butter, and various other articles. Mary Humby, servant to the prosecutrix, a widow lady, residing on Streatham-common, stated that on the night of the 11th of September [1840] she fastened the doors and windows previous to retiring to bed. She left the larder-window open, but secured before it an iron grating, which, on the following morning, between five and six o’clock, she found broken down, and a number of articles, named in the indictment, were taken away; there was also a thermometer taken from the side of the window.”

We need more evidence, clearly, and the verdict – although it rather seems an open-and-shut case, doesn’t it? The Weekly Dispatch obliges: “Inspector Campbell stated that on the 15th of September he went to the prisoner’s lodgings, and on searching his room discovered various property, and amongst it all the articles stolen from Mrs. Dare’s. Eleanor Evans said the prisoner had occupied a room in her house for about a month previous to his being taken into custody. He always locked his door when he went out, so that nobody had access to it. When called upon for his defence the prisoner said he purchased all the articles sworn to by the witnesses of a person in the street. The Recorder having summed up the evidence, the Jury returned a verdict of Guilty. The Recorder told the prisoner that he appeared to be an experienced and systematic robber. He had been convicted of two burglaries committed within three or four days of each other. It was quite impossible that he could be allowed to remain in the country. The sentence of the Court, therefore, was that he be transported beyond the seas for the space of ten years.”

For the location of the house concerned, we refer you at this point to our second source for this abominable crime perpetrated on Elizabeth Hall Dare, Mabel Bent’s grandmother, i.e. the Central Criminal Court, Minutes of Evidence (1840, Vol 12, p. 1059), which informs us that the property was in South London’s fashionable Streatham parish, an enclave of well-heeled souls in Victorian times.

The facts and characters of the case are a cross between Tom Jones and Much Ado About Nothing. It is worth extensively quoting, if for nothing more than a reprise of ‘burglarously’ – a word it’s doubtful you will encounter three times in your life, and for the true value of things:

“Christopher Johann Frederick Auguste Struve was again indicted for burglarously breaking and entering the dwelling house of Elizabeth Grafton Hall Dare, at Streatham, about twelve o’clock in the night of the 11th September, with intent to steal, and stealing therein, 1 towel, value 1s.; 2½ lbs. weight of butter, value 2s.; 1 bell, value 5s.; 1 butter-mould, value 6d.; 1 plate, value 1d.; and 1 cup, value 6d.; her property.

“Mary Hamby: I am single, and am cook to Mrs. Elizabeth Grafton Hall Dare, widow, of Streatham Common, in the parish of Streatham. On the night of the 11th of September the larder window was open, but there was a wire-guard inside before it, which must be broken to get at anything. I saw it safe a little after ten o’clock – it opens into the garden – the grating was secured by four large nails – the next morning I went down into the larder before six o’clock, and found the wire pushed quite round behind a milk pan, to prevent it going back to its place. I missed the articles stated. A person could get through the wire place – he had then opened a door out of the larder, and taken a white jug, bell, and drinking-horn – I lost a thermometer from outside the window.

“Prisoner: I bought these things of a man in the street.

“Eleanor Evans: I am the wife of John Evans and live in Church-street Minories. The prisoner lived with us four weeks and three days until he was apprehended – the policeman came to me, and I showed him his room – they found this jug, the bell and other articles there – nobody but him could have put them there, as the door was locked – I did not see the articles there till they were found – I had missed him two or three days before that, but did not know he was in custody.

“Samson Darkin Campbell: I am a police-inspector, of the V division. On the 15th of September I went with Pitcher to No. 51, Church-street. Evans showed me a room, and I found this towel, with the name of Hall Dare on it, a thermometer, a butter-strainer, two files, a pair of pliers, and some skeleton-keys, some of them unfinished.

“Thomas Pitcher (police-constable P 167.) I accompanied Campbell, and found these articles in the room – the prisoner was in custody at the time. (Property produced and sworn to.)

“GUILTY. Aged 41. Transported for Ten Years.” (‘Central Criminal Court, Minutes of Evidence’, Vol. 12, 1840, p. 1059)

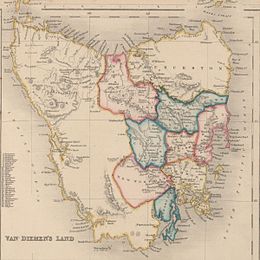

Researches are continuing into the life of Christopher Struve -could he have been a black sheep in the noble Struve family we can read about online? His convict records inform us simply that he was 41, married to Maria, had two girls, and was a Lutheran. We are still researching, too, exactly where in London’s fashionable Streatham it was that Christopher Struve decided to enter and remove therefrom a towel, a drinking-horn, a bell, a thermometer; and a quantity of butter – the most expensive thing in his swag, worth over £10 in today’s money. Wherever it was, it was a long way from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), something Christopher Struve wasn’t when he arrived in Hobart on 4 October 1841, transported in the yare David Clarke with 308 or so other men, one of whom (John Timbers, 19) died on the journey.

Probably in some form of restraint, it is unlikely that Struve met with the captain, William B. Mills, or saw that much of the Sound when they sailed from Plymouth on 7 June 1841 on that four-month voyage to Tasmania’s prison colony. Unloading her human cargo, the David Clarke sailed away again “for Bombay in ballast on 17 October 1841”; Christopher Struve remained, and we can imagine him coming ashore, almost exactly a year after his trial, contemplating the true value of a towel, a drinking-horn, a bell, a thermometer; all in all, it was a long, long way to come for a plate of butter.

We don’t know where these things are now, but they are not in the British Museum with the collections of Theodore and Mabel Bent.

For Mabel Bent’s diaries, see The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent (Archaeopress, Oxford)

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article