Muscat, Oman and Dhofar – November 1894 to February 1895

‘… in the early dawn it was really delightful to open my still sleepy eyes and, without moving, see the lovely picture passing before me of the beautiful mountains with their foreground of water; every fold and distance filled up and separated by soft vapours, and then the sunrise began to paint them red, and black shadows came and changed the shapes and presently all became hard and stony.’

With a rare moment of rhapsody we rejoin Mabel in Southern Arabia in January 1895, the couple having left London early the previous November. Mabel’s Chronicle details the couple’s second attempt to penetrate regions of the Hadhramaut, this time approaching from the south-east, via the coast of modern Oman, and their return, eventually, and again disappointed, from India in the spring of 1895. Mabel did not keep a diary for the month or so spent in India, but we know the couple were home in time for Theodore to prepare and present a paper for the Royal Geographical Society on 6 June 1895.

Following their return from their unsuccessful attempt to penetrate the interior of the Hadhramaut the previous season, Theodore had a busy few months over the summer of 1894 writing up and presenting his results to various institutions – within a month of arriving in London Theodore spoke to the Royal Geographical Society, participated at a function of the Royal Society (a long-term sponsor) on 13 June, and addressed (10 July) a special meeting of the London Chamber of Commerce (no doubt with an eye on future sponsorship). It is easy to imagine Theodore and Mabel surrounded by all their maps, photographs, notes, finds and specimens, working late at night in their comfortable rented home near Marble Arch, preparing what Theodore was going to say about the Hadhramaut and the frustrations they had faced.

Mabel’s previous Chronicle had ended in an upbeat tone with ‘and if we possibly can we’ll go back’. Perhaps the couple had already been planning another attempt on the Hadhramaut as they took the steamer back from Port Said to Marseilles. In any event they only had a few months (and they normally took a break in mid-summer to visit family and friends in England and Ireland) to seek backing and make all the necessary preparations, including informing the ‘media’. Theodore was well aware of the value of regular communications and was an able self-publicist. Ultimately he was ready to issue a ‘press release’ to The Times:

‘Mr. Theodore Bent informs Reuter’s Agency that he and Mrs. Bent are about to start another scientific expedition to Southern Arabia. Leaving Marseilles by Messageries steamer on November 12, they will proceed to Kurrachee, whence they will tranship to Muscat. On reaching the latter place they hope to be able to proceed to the Hadramaut Valley, which they explored last year. The journey being of very uncertain length, Mr. Bent’s final arrangements can only be made on reaching Muscat and ascertaining the feeling of the tribes through which country he would have to pass… Mr. Bent hopes to continue the archaeological and botanical work commenced last year, and the expedition is expected to return to England in April next.’ (The Times, 31 October 1894)

Before leaving London there was again much diplomatic activity before it was agreed that Imam Sharif could rejoin the party as surveyor. The absolute proviso was that Theodore should not encroach on Turkish interests. The Private Secretary to the Secretary of State made this extremely clear to the administration of the Royal Geographical Society: ‘I am…to request that you will inform Mr. Bent that, if he enters Turkish territory, he does so at his own personal risk, and Her Majesty’s Government cannot be held responsible for his safety.’ (4 October 1894, Horace Walpole to the Secretary, RGS (RGS Archives: arRGS/CB7/Bent, T&M)

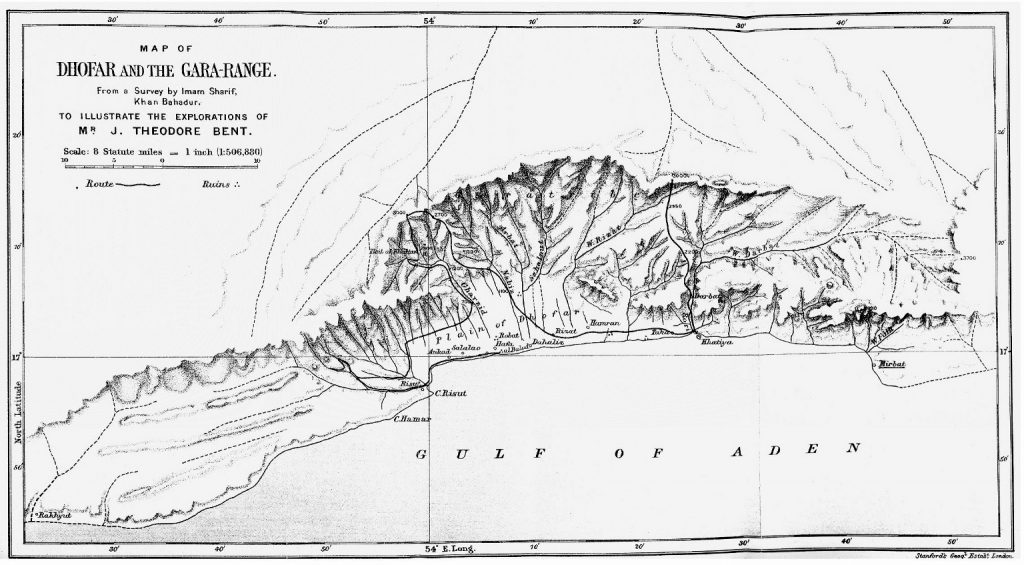

Arriving at Muscat in Oman in early December 1894, the couple’s first objective, the immediate mountainous hinterland to the west, the notorious ‘Empty Quarter’, was considered too dangerous and so they at once embarked for Merbat (Mirbat), several days south-west along the coast, and the southern district of Dhofar. From here they were to explore inland, along the old frankincense and myrrh trails, and Theodore was able to hypothesize on the locations of Ptolemy’s ‘Diana Oraculum’, as well as the lost coastal sites of Moscha and Abyssapolis: the latter proving to be the major discovery of this expedition.

Central to Theodore’s interests in the region was the ancient network of spice and resin trade routes that linked Southern Arabia, and its peoples, eventually with the Levantine coast to the north, and Africa, westwards across the Red Sea. In particular it was the frankincense trail, and the branch that began in Dhofar, that fascinated the explorer. Frankincense is a fragrant gum that dribbles from several species of Boswellia found in Dhofar (and the Southern Arabian coastal arc, including the Horn of Africa).

For this expedition the travellers had decided on a smaller party, without botanist and zoologist, Theodore and Mabel taking on these roles themselves. On 15 October 1894 Theodore wrote to Thiselton-Dyer, Director at Kew, to inform him that they planned to leave on 9 November and that ‘I have decided after much consideration not to take a botanist with us this year but if you can see your way towards helping me to take an Indian servant for the purpose I will undertake to collect myself. £30 ought to pay for this.’ Thiselton-Dyer replied that Kew would be pleased to receive any specimens from Oman.

The next phase of the journey was, somehow, to enter the inner Hadhramaut from the east. After discussion, their initial route, directly overland from Dhofar across difficult Mahri terrain, was deemed by Mabel as being beyond them, as her Chronicle of late January 1895 records:

‘The next 2 days there were great negotiations and plannings as to our future course. One plan was to go hence to Inat in the Wadi Hadhramout, down to Kabr Hud and Bir Borhut and thence to the Mosila Wadi; eastward and back by the coast to this place and then try to go westward. But the other is to us preferable; to go along the coast, first up Mosila and into the Hadhramout and then try to go West, without coming here again. Of course there are so many delays of all sorts that we shall be here some days yet.’

But the plans foundered. First at Qishn, and then Ash-Shihr, the party was refused access to the interior. So by early February 1895 the couple were resigned to making for Aden to tranship for India, where Theodore hoped he could get authorization and support for his return to the Hadhramaut. The reality of this second failure to explore the Hadhramaut is reflected in Mabel’s writing: it is the only Chronicle she fails to complete, or record their eventual return to London – as if she had, for the moment at least, lost heart. The few details to be had from Mabel she provides at the end of Chapter XXII in Southern Arabia: ‘We two and Lobo [assistant], whom we retained, went to a hotel in Bombay.’

Mabel’s Chronicle of this journey, and Theodore’s various articles, formed the nucleus of the relevant Dhofar chapters in Southern Arabia, written up by Mabel for publication three years after her husband’s death. Theodore’s articles and papers on the region are to be found in the bibliography on this site. There are no memorable artefacts in public collections from this expedition – but Theodore’s ‘discovery’ of the ancient centre of ‘Moscha limen’ (of Periplus renown), below ‘Abyssapolis’, remains another of his permanent contributions to archaeology. Of course, had Theodore and Mabel ventured and crossed the ‘Empty Quarter’ (as they say they originally intended on reaching Muscat) then their Royal Geographical Society medals would be heirlooms today.

The couple’s long-suffering Greek assistant, Manthaios Símos, has decided not to accompany the Bents on this expedition. Whether he was really frightened, as Mabel claims, we will never know.

It is time to rejoin Mabel as she catches up with her Chronicle, on Sunday, 15 December 1894, settled into the Residency at Muscat, as the couple prepare to embark on a journey that Theodore can later reminisce upon fondly:

‘The interests which centred in this small district – the ancient sites, the abyss, and, above all, the surprising fertility of the valleys and mountains, the delicious health-giving air, and the immunity from actual danger which we had enjoyed – combined in making us feel that our sojourn in Dhofar had been one of the most enjoyable and productive of any expedition we had hitherto undertaken, and that we had discovered a real Paradise in the wilderness…’ (Southern Arabia, p. 276)