The Bents – Great Friends of Kastellorizo

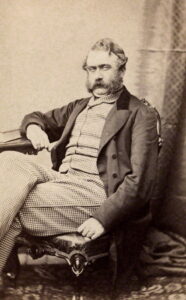

Just before (Western) Easter 1888, the tireless British explorers Theodore and Mabel Bent, on an extended cruise down the Turkish coast, had reached the small, thriving island of Kastellorizo – one more location to add to their twenty-year gazetteer; not a lot of people know that…

Wikipedia (03/09/2020) has plenty by way of introduction to this, perhaps the remotest of Greek islands one can step on via scheduled services:

“Kastellorizo or Castellorizo (Greek: Καστελλόριζο, romanized: Kastellórizo), officially Meyisti (Μεγίστη Megísti), a Greek island and municipality of the Dodecanese in the Eastern Mediterranean. It lies roughly 2 kilometres (1 mile) off the south coast of Turkey, about 570 km (354 mi) southeast of Athens and 125 km (78 mi) east of Rhodes, almost halfway between Rhodes and Antalya, and 280 km (170 mi) northwest of Cyprus.”

The previous year (1887), our explorers, Theodore and Mabel Bent, had been excavating way up north on Thasos, finding some important marbles (including a fine statue they were not allowed to take home), which are now in the archaeological museum in Istanbul. Denied their rightful gains (as they saw them), and never a couple to give up easily, the pair spent a good deal of the summer and autumn of 1887 trying to drum up enough support to have these marbles rescued from the Turkish authorities and cased up for London. Letters exist from Bent to the British Museum requesting their kind interventions (it all sounds very familiar): “We have indeed been unfortunate about our treasure trove but I have hopes still. I sent to Mr. Murray [of the BM] a copy of two letters which recognize the fact that I had permission in Thasos both to dig and to remove. These I fancy had not reached Sir W[illiam] White [our man in the City, see below] when you passed through Constantinople. Seriously, the great point to me is prospective. Thasos is wonderfully rich and I have some excellent points for future work and … I am confident we could produce some excellent results.”

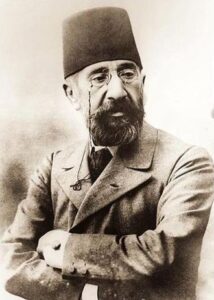

In January 1888, Theodore did receive a further grant of £50 from the Hellenic Society to return to Thasos to excavate, and the couple duly left for Istanbul. Unsurprisingly, the implacable, very capable Director of Antiquities in the Turkish capital, Hamdi Bey, refused Bent a firman to carry out further investigations, not only on Thasos, but also implying that the Englishman was not welcome to use unauthorized picks and shovels on Turkish lands in general.

Despite various appeals to canny career diplomat, the Ambassador, Sir William White, he and Mabel were forced to change their plans. Theodore may well have been expecting this. In the Classical Review of May 1889, his friend E.L. Hicks reveals that when Bent was first digging on Thasos in 1887 he had employed a local man to “to make some excavations in the neighbourhood of Syme” (far down the Turkish coast, north of Rhodes) on his behalf. Obviously satisfied with the results, the couple, after an excursion to Bursa to see the fabled Green Mosque, decided to return to Cycladic Syros, where they chartered for about fifty days the pretty yacht Evangelistria (the Bents refer to her as “the ‘Blue Ship’ from the gaudy colour with which her sides were painted”), with “Kapitan Nikólaos Lambros” and her crew, under Greek papers; and they embark (Wednesday, 29 February 1888) on this fall-back plan that will take them with the winds and currents as far south as Levantine, if not Oriental, Kastellorizo, frozen just off the Turkish coast, as a map will show you, like a mouse under a cat’s paw.

Meanwhile Mabel, on Syros before embarking, can be candid for her diary – they are to don pirate gear, “Theodore at once took to visiting ships to put into practice our plan of chartering a ship and becoming pirates and taking workmen to ‘ravage the coasts of Asia Minor’. Everyone says it is better to dig first and let them say Kismet after, than to ask leave of the Turks and have them spying there.” All, of course, reprehensible behaviour today. The couple also meet up here with their long-term dragoman, Manthaios Símos, who has sailed up from his home on Anafi , close to Santorini, to lend a hand.

Thus, on a sort of early tourist ‘gulet’ cruise (“There is a dog called Zouroukos, who was at first terrified… and the little tortoise, Thraki”), the couple’s investigations along the Asia Minor littoral (in particular the coastline opposite Rhodes) turned out fairly fruitful, and some of Theodore’s ‘finds’ from this expedition are now in London (see below). He briefly wrote up his discoveries of ancient Loryma, Lydae, and Myra for the Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 9, 1888 – but a lengthier account was provided by E.L. Hicks (Vol. 10, 1889)), including transcriptions of over forty inscriptions and passages of text from Theodore’s own notebooks.

No doubt his notebooks were to come in handy when, a few years later, Bent is editing his well-known version of Thomas Dallam’s diary for the Hakluyt Society (1893), recounting the latter’s adventures in these same waters: ‘The 23rd [June, 1599] we sayled by Castle Rosee, which is in litle Asia.’ (Incidentally, musical-instrument maker Dallam’s Gulliver-like exploits below the gigantic walls of Rhodes, not so very far away northish, are highly recommended.)

But back to the Bents, a popular account of the their 50-day cruise in 1888 – well worth a read for those who get off on the rugged coastline from Symi to Kastellorizo – was written by Theodore for The Cornhill Magazine, (Vol. 58 (11), 620-35), and entitled ‘A Piratical F.S.A.‘ (Bent had recently been made a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and was indulging in shameful hubris.)

(For the rest of Bent’s articles on this coastal meander, see the year 1888 in his bibliography.)

After various adventures, the Bents reached the Kastellorizo offing on 30th March 1888. Theodore sets the scene: “Great preparations were made for the arrival of the ‘Blue Ship’ at the first civilised port she had visited since leaving Syra. One of the ‘boys’, it appeared, understood hair-cutting, and borrowed Mrs. F.S.A.’s scissors for that purpose; beards were shaved, and shaggy locks reduced with wonderful rapidity… Castellorizo was the port, and it is a unique specimen of modern Greek [sic] enterprise, being a flourishing maritime town, built on a barren islet off the south coast of Asia Minor, far from any other Greek centre – a sort of halfway halting place in the waves for vessels which trade between Alexandria and Levantine ports; it has a splendid harbour, and is a town of sailors and sponge divers.”

Half thinking of home, the Bents are in need of some fancy paperwork to ensure their acquisitions thus far are protected from the prying eyes of both Greek and Turkish customs officials. Mabel’s ‘Chronicle’ gives us a little more, beginning with a sketch of their plans:

“First to go to the island of Kasteloriso, where there is a Greek consul, and have a manifesto made that we came from Turkey so that the Greeks may not touch our things in Syra… Now all was preparation for this civilized place. Theodore assured himself that his collar and tie were at hand. I hung out my best Ulster coat and produced respectable gloves and shoes… We really made a very tidy party when we reached our goal… We had a calm voyage. An average time from Myra to Kasteloriso is 6 hours; we took about 26. We did not land in the regular harbour. The captain said questions would be asked as to why there were 18 people in such a boat. We landed about 8. It is a flourishing looking little town, divided by a point on which rise the ruins of a red castle. The name should be Castelrosso, but first the Greeks have made it ‘orso’ and then stuck in an ‘i’. The Genoese or Venetians made it. Kapitan Nikólaos was greeted wherever he went by friends. He did not seem anxious to be questioned much, and once when asked where he had come from gaily answered, ‘Apo to pelago!’ (from the open sea). I was delighted at this answer and so, when some women, sitting spinning on rocks, called out, ‘Welcome Kyria,’ to which I answered, ‘Well met!’ and then asked, ‘Whence have you troubled yourself?’ ‘Apo to pelago!’ I smilingly replied and swept on round a corner where we could laugh, and who more than Kapitan Nikólaos…”

There is nothing in Mabel’s diary to suggest the couple made any sort of tourist excursion around the island, not even to the famous blue caves, which is a shame. Surprisingly, too, Theodore makes no mention of perhaps the most iconic ‘snap’ on the island, the Lycian rock-cut tomb (4th century BC), unique on Greek soil.

Mission accomplished, the next we learn is that the Evangelistria has reached the ancient site of Patara on the mainland: “Yesterday morning, Good Friday [March 30th], we had a very quiet voyage hither…”

Within days, Theodore and Mabel will be casting off for Syros once more, but, after 50 days in their gulet, they have had enough of open waters and decide to return to London the long way, overland, via Smyrna – Istanbul – Scutari – Adrianople – Plovdiv – Istanbul – Nicea – Istanbul – Odessa – Berlin. All a far cry from ‘civilised’, Levantine Kastellorizo… and one wonders of their dreams.

“We stopped 2 nights in Berlin at the Central Hotel”, writes Mabel, “We had travelled from Saturday night to Monday night, the 14th, and nearly always through forests. We crossed from Flushing and on Thursday [17th May 1888] we safely reached home… All our marbles reached England soon after, and after spending some weeks here are housed in the British Museum.” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent’, Vol 1, Oxford, 2006, p. 260)

‘Here’ is the couple’s smart townhouse near Marble Arch, a vast magpies’ nest, with every tabletop, bookcase and cabinet showing off souvenirs from 20 years of travels in Arabia, Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean, perhaps, too, some embroideries and large, distinctive chemise buttons (from the women Mabel chatted to on Kastellorizo), just arrived back in rough, pine crates, recently unloaded from the decks of the Evangelistria:

“The women here all wear the dress of Kasteloriso: long full coloured cotton trousers, then the shirt fastened down the front with… large round silver buckles, and then married women wear a gown slit up to the waist at the side. The 2 front bits are often tied back as they become mere strings. Then a jacket with sleeves ending above the elbow and very long-waisted, and very low is wound a scarf. The girls do not wear the gown. They have a fez on the head and a turban round it or not…” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent’, Vol 1, Oxford, 2006, p. 246)

For more on the Bents generally in the Dodecanese, see Further Travels Among the Insular Greeks (Archaeopress, Oxford)

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article