The Bents and the British Museum: in Five Objects

On 24 April 1885, British explorer Theodore Bent wrote from Syros in the Cyclades to Charles Thomas Newton, famous traveller himself and now Keeper of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum (BM): “We returned from Karpathos yesterday and had hoped to catch a steamer which would have brought us and our things straight to England. Unfortunately we shall have to wait a week at least, and as we have so much plunder we cannot take the Marseilles route. I had hoped to have been in time for the Hellenic meeting, but of course now we shall not reach England till the middle of May. We were fairly successful in Karpathos, finding a large number of rock cut graves unopened which have produced pottery, etc., which, if not of the highest order, offer a good deal which I believe to be of a new character… Of quaint manners and customs I have got a fine collection, also of old Karpathiote dresses and jewelry… We had rather a rough time of it, Karpathos being very far behind the world in comforts, and decidedly we enjoyed ourselves best when living in our own tent. Mrs. Bent survives and is well and begs her kind regards. Yours very truly, J. Theodore Bent.” (Mabel Bent 2006: 123, fn. 74)

(The Bents’ trip to the Dodecanese in 1885 was probably contributed to by the BM, and significant finds from there are now in London.)

To draw attention to, and thank the BM for their great and newly re-vamped online database, and make a nod to Neil MacGregor’s seminal TV/radio series, and subsequent exhibition, at the same time, the Bent Archive is selecting four significant objects to feature from the several hundreds of items (752, no less, the BM claim, though some are duplicated) either donated to or sold by Theodore and Mabel Bent to the Museum over a period of five decades or so from the 1880s, beginning with the artifacts Bent brought home from the Cycladic island of Antiparos, then an almost abandoned islet, today a hipster destination for some of Europe’s silliest teenagers; the Bents would be amused. The fifth item, as we shall see, is one that got away… but it should be there.

For about twenty years, Theodore and Mabel Bent travelled to regions in the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and Arabia, on the look out for things of archaeological and ethnographical interest (usually linked to Theodore’s current bonnet-bees and theories). Occasionally the British Museum contributed to the Bents’ travel costs on the understanding that the institution would get first refusal. We know that the museum also paid Theodore for certain acquisitions, but there were also donations from the Bents – in particular the large assemblage given by Mabel in 1926, a few years before her death (Theodore, alas, died early, in 1897).

The Museum’s archives (and elsewhere) contain much correspondence between Bent and their various curators and associated scholars, such as William Paton, Edward Lee Hicks, David Hogarth, Sir William Mitchell Ramsay, Charles Newton, Arthur Smith, Alexander Stuart Murray, Cecil Smith, William Henry Flower …

Good examples of these interactions include a letter from Theodore to the Keeper at the British Museum, dated 30 May 1884: “Dear Sir, Do you care to make me an offer for my figures, vases, ornaments, etc., from Antiparos? It occurs to me that a collection of this nature is rather lost in private hands. Yrs truly, J. Theodore Bent.” (Mabel Bent 2006: 46, fn. 49)

The BM archives also include the Museum’s day books and accession registers, fascinating records that bring you closer to collector and curator, in contexts of mutual scholarship, curiosity, and wonder.

This is not the place to comment on the history of the Museum, collectors’ activities, or the acquisition policies current in the late 19th century. You will have your own thoughts and opinions.

The objects collected by the Bents are featured below, in a sort of virtual ‘The Bents at the BM’ mini-exhibition, by the date they were acquired by the Museum, and representing the main regions of the Bents’ fields of studies, as already mentioned – the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and Arabia, over a period twenty years following their marriage in 1877. In most cases the BM item number consists in part of the year the piece was acquired from the Bents, i.e. Af1892,0714.144, denotes 1892 – in this instance when Theodore and Mabel returned out of Africa.

Thus, without further ado… “The Bents and the BM: in Five Objects”

Let’s make a start in the Greek Cyclades – the scene of Theodore’s first (1883/4) substantial ‘excavations’ (although his modus operandi bears little resemblance to the science of today and raises eyebrows, if not ire, still among archaeologists).

[Basic inventory details are provided, but there seems little point in repeating the detailed information on the artefacts given by the Museum, click through yourself to access it if you wish. We thought however that readers might like to get a little detail on the objects provided by the Bents themselves, either via Mabel’s diaries (her Chronicles), or Theodore’s publications.]

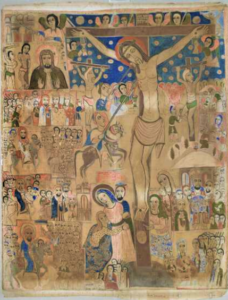

(For a detailed study of this unique piece, see ‘The image revealed: study and conservation of a mid-nineteenth-century Ethiopian church painting’, by Heidi Cutts, Lynne Harrison, Catherine Higgitt and Pippa Cruickshank, in The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin, Vol. 4, 2010: 1-17.)

The Bents’ 1883 tour of the region was ultimately unsuccessful due to local unrest, exacerbated by the colonial ambitions of the Italians. By far the most interesting of the artifacts Bent brought back was this large painting of the Crucifixion, he bought for ‘Ten pieces of silver’ from the Church of the Saviour of the World, Adwa. Bent describes the transaction in the book that resulted from the journey: “It was here… that I espied a picture cast on one side, for the colours were somewhat faded, which I faintly hoped to acquire. At first our offers were received with contempt, but again and again we sent our interpreter, and with him ten pieces of silver, the sight of which eventually overcame the priest’s dread of mutilation, and the evening before our final departure from Adoua the picture was ours. Our interpreter himself was terrified at what he had done, ‘We must not breathe a word of the transaction, even to the Italians,’ he said ; ‘we must bury the treasure at the bottom of our deepest bag ‘ ; and to all these regulations we gladly acquiesced, for we knew the great difficulty of acquiring these things in Abyssinia, and the danger to which we all should be exposed if our transaction should be discovered, and I am pretty nearly sure that this picture which is now in the British Museum is the first of its kind which has reached Europe…” (The Sacred City of the Ethiopians, 1893, pp. 129-33)

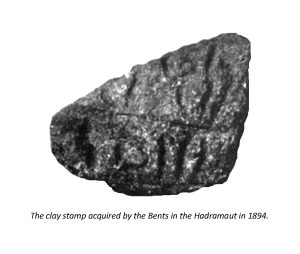

[Cultured female voice, slow, musical, dark, clear] “Object No. 5: A pottery stamp/clay seal from the Wadi Hadramaut, Yemen, aka ‘The Bethel Seal’? Used presumably by a merchant for designating ownership, or contents, of traded merchandise. Date uncertain.” It must be quickly said that this is a deceit; it is a mystery object that should have been given by Mabel with a few other artifacts from the Wadi Hadramaut (Yemen) in 1926, but was not, and thereby hangs a tale worth the telling.

[Cultured female voice, slow, musical, dark, clear] “Object No. 5: A pottery stamp/clay seal from the Wadi Hadramaut, Yemen, aka ‘The Bethel Seal’? Used presumably by a merchant for designating ownership, or contents, of traded merchandise. Date uncertain.” It must be quickly said that this is a deceit; it is a mystery object that should have been given by Mabel with a few other artifacts from the Wadi Hadramaut (Yemen) in 1926, but was not, and thereby hangs a tale worth the telling.

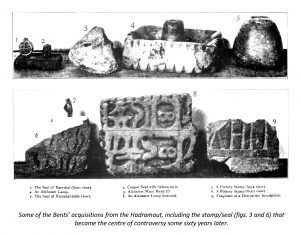

The Bents are admired for their three attempts to traverse the dangerous Wadi Hadramaut in the Yemen, from west to east and down to the Gulf of Aden, from 1894-7. The final trip cost Theodore his life. The couple were travelling on horses and camels and were restricted in what they could bring away with them and the largest collection consisted of hundreds of botanical specimens, reasonably light, now in the Herbarium, Kew.

Mabel has left us in her diary some idea as to how acquisitions were made along the way: “On Saturday the 13th [January 1894], the day after our arrival, at 8 o’clock, the Sultan, Theodore, Saleh and a groom on the four horses, and I on [my horse] Basha, and a vizier on a camel with a soldier, and the soldiers on foot, rode about five miles to a good old ruin (Al Gran), but embedded in an inhabited house so that excavation would be impossible; from a very well cut scrap of ornament we thought it to be a temple, and it is perhaps from this temple that a kind of small stone trough has been brought, with a dedication, rather long, in Sabean, which Theodore has nearly deciphered – a trough with a spout coming to England. Two stones have been brought us by camels at the Sultan’s orders.” (Mabel Bent 2010: 167)

The Bents returned in 1894 from the Hadramaut with the modest lump of clay – the stamp/seal in question. It featured with a small collection of other items on page 436 of the Bents’ great book on Southern Arabia (1900), including the ‘trough’ Mabel mentions above. Then, rather like a great ring, the seal disappeared from view – until it reappeared in an archaeologist’s shovel in the late 1950s at a site at Beitin, Biblical Bethel, Palestine, and the scene of Mabel Bent’s accident in the early 1900s, when she broke a leg in the wilderness, riding, unaccountably, on her own.

The Bents returned in 1894 from the Hadramaut with the modest lump of clay – the stamp/seal in question. It featured with a small collection of other items on page 436 of the Bents’ great book on Southern Arabia (1900), including the ‘trough’ Mabel mentions above. Then, rather like a great ring, the seal disappeared from view – until it reappeared in an archaeologist’s shovel in the late 1950s at a site at Beitin, Biblical Bethel, Palestine, and the scene of Mabel Bent’s accident in the early 1900s, when she broke a leg in the wilderness, riding, unaccountably, on her own.

But was it the same modest lump of clay, or another, identical artifact? Today it (or both?) is/are lost, and a debate has waxed and waned over the mystery ever since. A strong argument is made that Mabel, distressed, widowed, mourning her late husband and her lost life as an explorer, ceremoniously placed the stamp in a deposit at Bethel in the early 1900s as a tribute to Theodore – not caring if it were ever found again or not – the significance of the site being that it marked the end of a frankincense route (the resin being one of his passions) that began thousands of miles away in the Wadi Hadramaut – and thus Theodore could rest easily, his journey over; the love of a grieving widow.

For a scholarly overview of the seal in context, see ‘Arabian and Arabizing Epigraphic Finds from the Iron Age Southern Levant’, by Pieter Gert Van Der Veen with François Bron, in J.M. Tebes (ed.) Unearthing The Wilderness: Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age: 203-226. Leuven: Peters.

As a coda, perhaps the Bents’ acquisitions no longer quite justify the hyperbole appearing in Mabel’s interview to The Hearth and Home (2 November 1893) before leaving for Arabia: “Gifted with great artistic taste, Mrs. Bent’s personal collection of curiosities include many beautiful things brought from abroad, and, as our readers are doubtless aware, ‘The Bent Collection’ in the British Museum is one of the most interesting in that venerable building.”

But you should go and decide for yourself…

References: Mabel Bent 2006, 2010, 2012 = The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent, vols 1-3, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Other finds: Very much smaller collections of the Bents’ acquisitions can be found in: the V&A, London; the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford; as well as in Cape Town, Harare, Istanbul, and elsewhere.

Don’t overlook, too, the wonderful, though small, collection of dried plants in the Herbarium, Kew Gardens. Most of the specimens were collected by Kew’s William Lunt, who travelled to the Hadramaut with the Bents in 1894, but there is some additional material from their later expeditions. Kew’s super online catalogue (with some illustrations) makes a great start.

It should also be remembered that in the late 19th century London’s Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name ‘British Museum (Natural History)’. Thus the select assemblage of molluscs, insects and reptiles the Bents collected was gradually transferred to their care, e.g. we know that Mabel presented her collection of 186 “land and freshwater shells from the island of Socotra, including several new species”. (For publications on the shells, see, e.g. J.C. Melvill, Journal of Molluscan Studies, Vol. 1, Issue 5, 224-5).

Very importantly, the skeletal material Bent removed from two sites on Cycladic Antiparos in 1884, believed lost but now rediscovered, is stored in the National History Museum, awaiting further study.

(In 1926, a few years before she died (1929), Mabel had a sort out of the things she still treasured in her London home. This explains why many of the inventory numbers in the above museums have a 1926 date.)

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article