Following on from Alan King’s well-researched, recent piece (September 2019) on the Bents’ friends William (1857-1921) and Irini (1869/70-1908) Paton, it was a pleasant surprise to have access to two unpublished letters from the Paton great estate, Grandhome, just outside Aberdeen – Bent to Paton. In their correspondence, the men refer to recent explorations and successes in Cilicia (notably Bent’s discovery of the site of Olba), and the second letter is of particular interest in terms of Bent’s almost immediate departure for Great Zimbabwe, perhaps his most notorious work. These two letters are published below for the first time and we are most grateful to the present William Paton, Bent’s friend’s great-grandson, for kindly allowing us this opportunity.

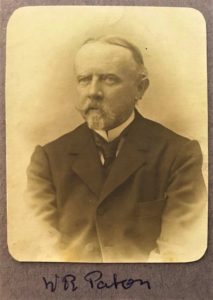

Laird William Paton was a fascinating man of complex nature – a great, perhaps maverick, classicist, traveller and philhellene – it’s not hard to see in him the early shades of later and similar great names, why not Leigh Fermor, Durrell, Pendelbury, Dunbabin…? One can make a fair list.

The only son, William becomes laird of Grandhome after the death of his father, John, in 1879, a JP in 1884, and Deputy-Lieutenant in 1893. But by the mid 1880s he has settled on Kalymnos, running his Scottish estates and managing his responsibilities from a great distance, obviously with a team at home to oversee things (his elderly widowed step-mother, Katherine, survived until 1919), and relying on regular trips back to north-east Scotland: and this trip home from the isles of Greece (then Turkish), by steamer, presumably via Marseilles (the same way the Bents travelled) and Dover and Edinburgh, to Aberdeenshire – a distance of some 4000 km each way; but the Scots are tough and he was young.

Of the two, Bent and Paton, the latter was five years older, and taller, but this didn’t prevent them apparently from being mistaken for bothers, as Mabel Bent was quick (even proud?) to note in her diary:

“We were very much amused on landing [on Kalymnos] to hear ‘William has returned’. ‘No, it is his brother.’ ‘He is exactly the same.’ ‘How very like he is.’ ‘No, it is not him.’ And these sentences never cease to be buzzed round wherever T[heodore] goes. At the British Museum they have been taken for one another and a gentleman came and shook hands with him and said ‘When did you come’ and then ‘Oh! Excuse me. I thought you were the son-in-law of Olympidis’.” (The Dodecanese; Further Life Among the Insular Greeks, Theodore and Mabel Bent, Oxford, 2015, page 159)

Both young men went to Oxford and were intended for the Bar, but both were side-tracked by the lure of ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. Bent had studied history at Wadham and his early studies took him in search of Genoese adventurers on Chios and elsewhere. Paton, the young classicist of rigourous intellect, and self-confessed ‘Orientalist’, soon found himself after University College, hunting for pots and publishing inscriptions in Lycia and Cilicia, inter alia.

Surprisingly, promptly marrying the obviously beguiling and young Irini Olympiti, he settled on Kalymnos, nowadays a municipality in the southeastern Aegean, belonging to the Dodecanese, between the islands of Kos and Leros, and 20 km from the Turkish coast opposite. Soon, along with the even more erudite E.L. Hicks, later Bishop of Lincoln, and also a Bent collaborator (but, another story), Paton became a go-to-man for British academics wanting advice on the region.

Thus, although a truer scholar than Theodore Bent, it is quite natural that they should have met and become acquainted, both lovers of ancient Greece, the new discipline of archaeology, and working on inscriptions in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 1880s; as Mabel noted above, they often bumped into each other at the British Museum, the offices of the Hellenic Society, and many academic events in London and elsewhere.

And we know that Bent at least once travelled up to Aberdeen to stay with Paton, the latter reminiscing in a letter, from Vathy on Samos, in the early 1920s: “I also had the privilege of meeting [E.L. Hicks] personally… at my own house in Scotland, where the late Mr. Theodore Bent and Professor W. M. Ramsay were present, and I had the full advantage of the conversation of these three distinguished people…”

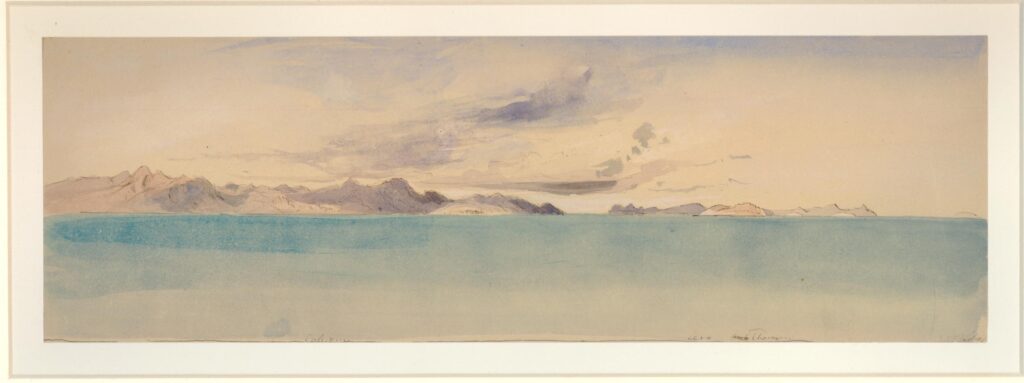

Edward Lear on Greece

“It seems to me that I have to choose between two extremes of affection for nature – towards outward nature that is – English or southern – the former, oak, ash and beech, downs and cliffs, old associations, friends near at hand, and many comforts not to be got elsewhere. The latter olive – vine – flowers, the ancient life of Greece, warmth and light, better health, greater novelty, and less expense in life. On the other side are in England cold, damp and illness, constant hurry and bustle, cessation from all topographic interest, extreme expenses…” [Edward Lear, c. 1860, taken from a letter, in Edward Lear: A Biography by Peter Levi (1995, p. 192)]

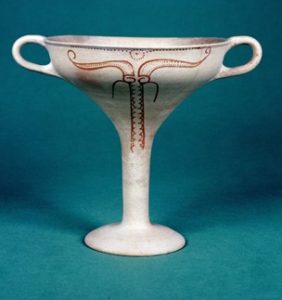

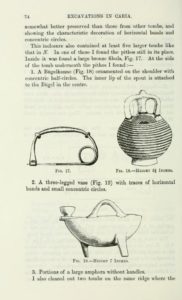

By the mid 1880s, William’s reputation as an epigrapher (and archaeologist, in the terms of the day) was in the ascendancy; any of his published papers reveal a clarity, ingenuity and level of scholarship that soon marked him out. His first major work was at the site of Assarlik (Caria), on the Turkish mainland, on a steep mountain-top in the southern part of the Halicarnassus peninsula, the site offering a perfect view of the coast, both east and west.

He is to publish his findings (1887) as ‘Excavations in Caria’ (JHS 8, 64-82), with, coincidentally, Theodore Bent having an article on inscriptions from Thasos in the same issue (pages 409-438). William had a further piece on ‘Vases from Calymnus and Carpathos’ in the same volume (pages 446-460).

In 1900, the University of Halle awarded him an honorary degree.

W.R. Paton: A select bibliography

1891: The Inscriptions of Cos (With E.L. Hicks)

1891: The Inscriptions of Cos (With E.L. Hicks)

1893: Plutarchi Pythici Dialogoi tres.

1896: (with J.L. Myres) “Karian Sites and Inscriptions”, JHS 16: 188-271.

1898: Anthologiae Grecae Erotica, London, David Nutt.

1899: Inscriptiones insularum maris Aegaei praeter Delum, 2. Inscriptiones Lesbi, Nesi, Tenedi, Berlin.

1915-18: “Greek Anthology”, vols 1-5, Loeb Classical Library/Heinemann, London and New York.

The two previously unpublished letters (1890) from Theodore Bent to William Paton

Letter 1

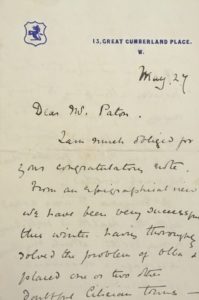

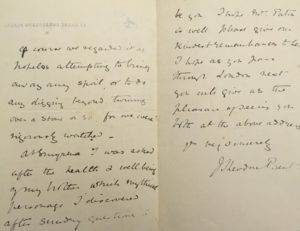

To W.R. Paton, Grandhome, Aberdeen, Scotland [no envelope] note 1

13 Great Cumberland Place, W. note 2 May 27 [1890]

Dear Mr Paton

I am much obliged for your congratulatory note.

From an epigraphical view we have been very successful this winter, having thoroughly solved the problem of Olba and placed one or two other doubtful Cilician towns. note 3

Of course we regarded it as hopeless attempting to bring away any spoil or to do any digging beyond turning over a stone or so, for we were rigorously watched. note 4

At Smyrna I was asked after the health and well being of my brother, which mythical personage I discovered after sundry questions to be you.

I hope Mrs Paton is well, please give our kindest remembrances to her. note 5 I hope as you pass through London next you will give us the pleasure of seeing you both at the above address.

Yours very sincerely

J Theodore Bent

Letter 2

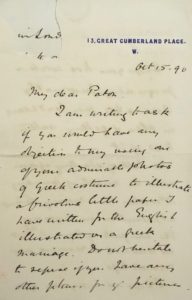

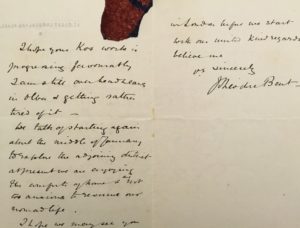

To W.R. Paton, Grandhome, Aberdeen, Scotland [no envelope; the Bent family crest has been torn from the top-left corner] note 6

13 Great Cumberland Place, W. note 7 Oct 15, 1890

My dear Paton note 8

I am writing to ask if you would have any objection to my using one of your admirable photos of Greek costume note 9 to illustrate a frivolous little paper I have written for the English Illustrated on a Greek marriage. note 10 Don’t hesitate to refuse if you have any other plans for your pictures.

I hope your Kos work is progressing favourably. note 11 I am still over head and ears in Olba and getting rather tired of it. note 12

We talk of starting again about the middle of January to explore the adjoining district. note 13 At present we are enjoying the comforts of home and are not too anxious to resume our nomad life.

I hope we may see you in London before we start.

With our kind regards, believe me

Yours sincerely

J Theodore Bent

Postscript

As a PS, there are two addenda; one a granite obituary in the Aberdeen Daily Journal of 14 May 1921 that covers well the life-journey from Aberdeen to the Greek and Turkish isles:

“The late Mr W. R. Paton of Persley, Eminent Greek Scholar. Greek scholarship has sustained a severe loss in the death of Mr William Roger Paton of Grandhome and Persley, Aberdeenshire, which took place at Vathy, Samos, New Greece [sic], on April 21, in his 65th year. The son of the late Colonel John Paton of Grandhome, the deceased, who was regarded as one of the finest classical scholars in Europe, belonged to a very old and highly respected family which had been in possession of the estate of Grandhome and mansion-house, situated between Parkhill and Stoneywood, for at least 200 years. A number of Mr Paton’s ancestors are buried in Oldmachar Churchyard, and the records of the family go back to 1700. Educated at [Eton] and at University College, Oxford, Mr Paton very early acquired a strong interest in everything connected with Greece, and particularly with Greek literature. He had already done a good deal of Greek study before he left in 1893 to take up his residence in France. For a number of years he had lived in the island of Samos, in the Aegean Sea, travelled in Asia Minor and among the Isles of Greece, and made a number of important contributions to Greek literature. In particular, he edited the works of Plutarch, and was preparing a large edition at the time of his death. He also collected many inscriptions found in the Aegean Islands; and his archaeological discoveries in Lesbos, Tenedos, and other isles of the Greek Archipelago were communicated to the Berlin Academy and form part of the Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum. He published an edition with translations of the love-poems and epigrams in the Greek Anthology. Mr Paton was recognised as one of the greatest Greek authorities of his time. His scholarship was of a very finished character, and he had also a wide knowledge of modern Greek. No one really knew more about Greek life, thought, and literature in all periods, and he was man of remarkable accomplishments, who if he had not been a country laird would have adorned a University chair… In 1900 the University of Halle conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws on Mr Paton. Personally Mr Paton was a man of charming manners and a delightful companion of the most finished culture. A year or two ago he was expected to come home and spend the end of his days in Aberdeen, but he did not carry out his intention. Mr Paton was twice married to Greek ladies, and he leaves a widow and family. He died on 21 April 1921 in the town of Vathy, Samos.”

A final and quirky note goes to J.H. Fowler, who was in touch with Paton while compiling a memorial volume to E.L. Hicks (see above). He gives us this astonishing, perhaps envious, pen-portrait of Paton:

“At this time too [Hicks] became associated with another Greek scholar, Mr. W. R. Paton, who took up his abode in the Island of Cos and made a careful collection of the inscriptions to be found there. Hicks collaborated in the deciphering and interpretation of the inscriptions, and wrote the introduction for the Inscriptions of Cos (Clarendon Press, 1891). A friendship grew up between the two men, unlike as they were, the one equally at home in the practical and in the theoretical life, the other a dilettante scholar who became at last so completely ‘orientalized’ (to use his own expression) that he was reluctant to revisit England, and who never earned anything in his life till he was paid for his translations from the Greek Anthology in the Loeb Library.”

Notes to Letter 1

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Notes to Letter 2

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

Return from Note 8

Return from Note 9

Return from Note 10

Return from Note 11

Return from Note 12

Return from Note 13

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article