What follows is a brief introduction to the Bents’ extensive and productive explorations of Greece and Turkey in the 1880s and subsequently, divided into their 7 tours and two further visits (see the interactive map):

- Tours 1 and 2 (1882/3 – Including Smyrna, Chíos, the Greek mainland and the Cyclades & 1883/4 – the Cyclades)

- Tour 3 (1885 – The islands today known as the Dodecanese)

- Tour 4 (1886 – From Istanbul and along the Turkish coast)

- Tour 5 (1887 – From Istanbul and into the northern Aegean)

- Tour 6 (1888 – From Istanbul and along the Turkish coast)

- Tour 7 (1890 – Further researches along the Turkish coast and into Armenia)

- Two further visits to Greece: 1896 & 1898

- View the interactive map of the Bents’ journeys

The Bents’ visits to the islands of the Cyclades were recounted in Theodore’s 1885 book – see The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks. For the full Chronicle texts covering these seasons, see Mabel Bent’s Chronicles, Volume 1: Greece and the Levantine Littoral (Archaeopress 2006).

Tours 1 and 2 (1882/3 – including Smyrna, Chíos, the Greek mainland and the Cyclades & 1883/4 – the Cyclades)

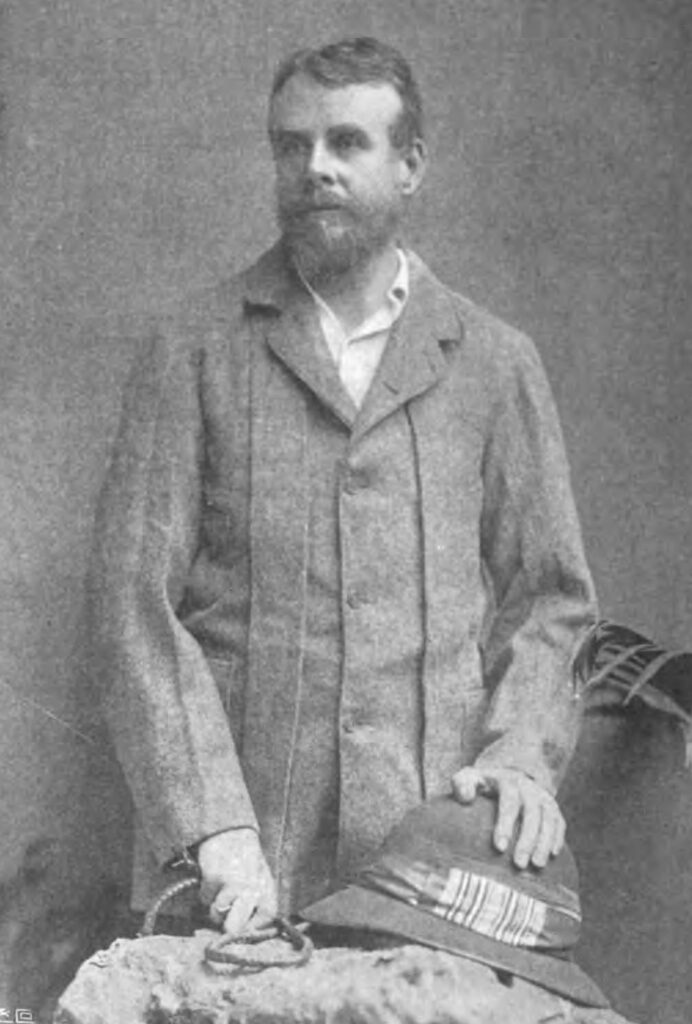

After their marriage on 2 August 1877, at a small church not far from Mabel’s childhood home, Newtownbarry House, County Wexford, Theodore and Mabel begin their twenty-year series of regular annual travels. Having decided a barrister’s life was not for him, and with a career as an historian, perhaps, ahead, Theodore guides his new wife down through to Italy, which they revisit over the next few seasons. These tours result in a sequence of short monographs (see Bibliography) and articles on, amongst other topics, Garibaldi, Genoa, and San Marino (they both henceforth proudly acknowledge the honour conferred on them of ‘citizenship’ of that little republic).

‘…these islands, especially the smaller ones, offer unusual facilities for the study of the manners and customs of the Greeks as they are, with a view to comparing them with those of the Greeks as they were…’ (from the Preface to Theodore’s The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks).

It seems that Mabel left no account of these early Greek travels, but there are several references to them in her Chronicles, as well as in the many articles written by Theodore subsequently, in particular his contentious paper ‘Two Turkish Islands Today’ (Macmillan’s Magazine/Littell’s Living Age, September 1883), protesting conditions on Sámos and Chíos. It caused quite a stir (Arthur Evans had written on a similar theme a few years before) and questions were even raised in the House; Theodore was to regret the consequences as, understandably, the Turkish authorities were less than enthusiastic to his requests to research in their territories in future.

That first trip prepared the way for a further six years of extended voyages around Greece and Turkey, and kindled in Theodore an interest in ‘archaeology’ (essentially removing objects for sale or donation to English institutions), which, from then on, was to assume equal importance for him to his historical and anthropological enquiries into the regions he chose to explore.

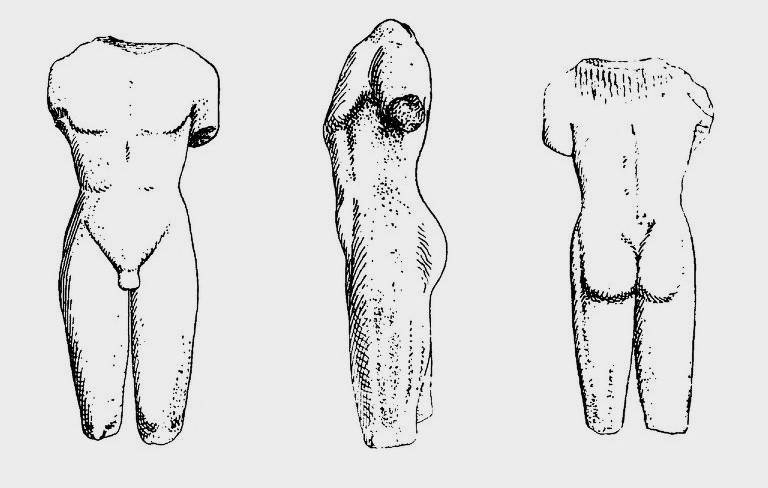

November 1883, therefore, sees the couple start their second trip together to the eastern Mediterranean. What Theodore had seen in the Cyclades in the spring of 1883 convinced him that a little ad hoc spadework on these little islands might produce some tangible rewards. He was right; his discoveries on Antiparos led to new theories for a distinct ‘Cycladic culture’ sandwiched, geographically if not always chronologically, between the Minoan and the Mycenaean. He and his small team of excavators found several unopened graves, and there is a letter from Theodore, dated 30 May 1884, to the Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum enquiring, ‘Do you care to make me an offer for my figures, vases, ornaments, etc., from Antiparos? It occurs to me that a collection of this nature is rather lost in private hands.’ These artefacts now form the core of the Bronze Age Cycladic collection in Great Russell Street, and were first published in the Journal of the newly established Hellenic Society shortly after the couple’s return in 1884.

Mabel’s Chronicle of these months provided her husband, in addition to his own notes, with much of the material he used to write what has remained the most entertaining of English accounts of the area, The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks (London, 1885). It is clear that Theodore relied heavily on his wife’s journals to help him when it came to the writing-up stages of his own material; he often quotes her verbatim, especially relying on her for colourful references to costumes, customs, board and lodgings.

On their 1882/3 trip the Bents employed a translator (Kostandinos Verviziotes) for the Greek mainland, and one George Phaedros of Smyrna for their tour of the islands. For 1883/4 they decided to reemploy George as their dragomános, or translator/factotum. His efforts, however, are less than satisfactory and he is ‘let go’, on Náxos, in favour of Manthaios Símos of Anáfi. They meet, casually, in a remote mountain village on Náxos, but it turns out to be the beginning of a relationship that is to last until Theodore’s death in 1897. With only a few exceptions, Manthaios is to rejoin the British travellers every season on their explorations. In their early years in Greece, before they both acquired the language, their new dragoman was invaluable in terms of helping with provisions, travel and accommodation. There were then no hotels between Sýros and Crete, and the couple had to rely on local hospitality – towards which they were usually expected to contribute – or their own tents.

They transported a large amount of luggage with them, augmented all the time, it seems, by archaeological finds, souvenirs, and, especially, embroideries and fabrics. Their possessions included a much-used medicine chest; both Mabel and Theodore considered it their duty to provide medical care when they could. On Ándros, Theodore was in need of treatment himself, and we hear of the first in a series of fevers to which he was susceptible.

A feature of her Chronicles is Mabel’s (often gossipy) references to her fellow travellers and other characters they meet along the way – particularly in capital cities and towns, and on board various, very slow, steamers. These cast-lists include Empire servants, missionaries, archaeologists and scholars, friends, occasionally family, and casual acquaintances. chance, characters we have met before on these remote islands. Worthy of note from the 1883/4 Chronicle are the Swan brothers, John and Robert, calamine miners, living and working on Andíparos. They become firm friends and Robert, in 1891, joins the Bents as a specialist engineer on their journey to Africa.

Mabel’s long series of notebooks (her Chronicles) is to begin at the end of November 1883, with Volume 1 accompanying its owner from London to Calais – Naples – Athens – around the Cyclades – Athens – Corinth – Corfu – Brindisi – Ancona – Loreto – Bologna – Bellinzona – Basle – Calais, and finally returning home again to 13 Great Cumberland Place, London, by mid-April 1884.

Tour 3 (1885 – the islands today known as the Dodecanese)

In the new Greece, controls and restrictions on individuals wishing to excavate were making it increasing difficult for freelancers such as Theodore Bent. So where should the couple try next? In the Journal of Hellenic Studies for 1885, Bent hints, ‘Before going to Karpathos last winter a passage in Ludwig Ross’s Inselreisen excited my curiosity…’ (JHS 6, 1885). His reference was to the little visited region in the north of Kárpathos, and the couple accordingly made plans to visit the islands around Rhodes, deciding to arrive there, with Turkish papers, via Egypt.

Mabel and Theodore arrive on Rhodes in February 1885, from Alexandria. They had been sightseeing in Egypt for the last few weeks. (For a birthday treat to herself, in January, she climbs one of the Pyramids at dusk, alone. The islands we think of today as the Greek Dodecanese then formed part of the Ottoman Empire. Theodore is rather anxious that the debate stirred up by his 1883 article criticizing Turkish rule on Chíos might hamper his chances of excavating; his choice of entry from Alexandria, rather than Istanbul, reflects this. The couple prefer to keep a low profile and they think it best to avoid asking for permission to explore and excavate unless absolutely necessary. However, Turkey was then more amenable to parties of foreign archaeologists and the Asia Minor coast had been revealing considerable riches, especially inscriptions and architectural and sculptural remains. The Bents were to focus on the Ottoman provinces for the next five years.

Theodore wrote up his 1885 finds in a paper for the Journal of Hellenic Studies, in particular his productive stay on Kárpathos (after a few days exploring Tílos). It is on this tour that he and Mabel acquire the odd limestone statue she describes as ‘the most hideous thing ever made by human hands’, and which now stands grotesquely in its case in the British Museum. The Hellenic Society (of which Mabel becomes a member in this year) are less subjective, opining that ‘The objects brought by Mr. Bent from Carpathos were of great interest, and especially one rude figure, which might be regarded as the earliest specimen of an idol of any size from the Greek islands…Possibly these were the idols of the primitive Carrian race.’ (JHS 6, 1885).

After their excavations on Kárpathos, the travellers have an exciting journey home, by way of an enforced stopover on Crete and Malta.

Mabel’s 1885 Chronicle runs from January to May of that year. The couple leave their London townhouse for Dover – Calais – Marseilles – Naples – Cairo – Alexandria – Rhodes – Nísiros – Tílos – Kárpathos – Crete – Kýthera – Sýros – Sicily – Malta – London (Millwall Docks).

Manthaios Símos is hired once more as general assistant and he joins the couple on Rhodes after several delays. There is no reference to any remuneration for his considerable services, but for the four months he spent with the couple in Arabia in 1889 he was paid £50. Importantly, this Chronicle contains Mabel’s first reference to her role as expedition photographer, a function she fulfilled enthusiastically, but with mixed results, for all the couple’s subsequent travels. Very few of her plates or negatives have survived and the technical problems she had to deal with were considerable.

This is a happy trip for the couple, with time spent on unspoiled islands that still offer much of the charm enjoyed by the Bents. Mabel is free with her likes and dislikes of the characters they meet, and her pages detail their problems with Ottoman officials – a theme that is to recur. At consular parties on Rhodes she chats to names of some note in archaeological circles, including Alfred Billiotti, career diplomat and enthusiastic excavator of the principal sites on the island, among them Kamiros and Ialysos, and Frank Calvert, the keen part-time archaeologist who first suggested that the site of Hissarlik might be Homer’s Troy. A sadder reference is to General Gordon, who was killed at Khartoum in January 1885.

Tour 4 (1886 – From Istanbul and along the Turkish coast)

Mabel begins her 1886 Chronicle in Istanbul. She is chatty and happy and gives an insight into her motives for writing: ‘to remind myself in my old age of pleasant things (or the contrary)’. She also takes the opportunity of reinforcing her insistence that she is writing notebooks not guidebooks… ‘I do not, of course, intend to describe this town but only our adventures therein.’

Following the successes of their 1885 work further south, the Bents decide for this season to cruise down from the Turkish islands of Sámos and Chíos, which they had first seen in 1882/3. Theodore, now a member of the council of the Hellenic Society, had obtained a grant of £50 to equip his expedition. Once on Sámos he encountered problems with the authorities, and the Society’s journal of 1886 reports that, ‘owing to unexpected difficulty in obtaining permission to dig in the island, Mr. Bent has not been so successful as he had hoped. He has, however, spent only half the amount.’ The £25 was returned to the Society. Mabel informs us: ‘Truly the balmy days of excavators are over’. [The Autumn/Winter 2021 edition (pages 40-43) of ARGO – the Journal of the Hellenic Society – has a short illustrated article on these grants.]

Theodore (with Percy Gardner’s help) provided a summary of his work in the region for the Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 7, 1886, pp. 143–153), under the title ‘An Archaeological Visit to Samos’. He begins his introduction: ‘English enterprise in excavation has been considerably checked of late years by the impossibility of obtaining anything like fair terms from the Greek or Turkish governments… Consequently if English archaeologists wish to prosecute researches on the actual soil of Hellas, it remains for them to decide whether they are sufficiently remunerated for their trouble and outlay by the bare honour of discovering statues, inscriptions, and other treasures to be placed in the museum of Athens, or, as is the case in Turkey, for the inhabitants to make chalk of, or build into their houses.’ Theodore was piqued.

The British Museum has some of Theodore’s Samian finds. He uncovered a terracotta mask and copied an important inscription listing victors at games held within the famous sanctuary of Hera. But the couple were disappointed and leave Sámos early to undertake preliminary researches around the neighbouring islands. (Since the infamous episode of the kidnap and murder of British tourists at Dilessi on the Greek mainland in 1870, wealthy foreigners were well advised to travel armed. Mabel records at length their many schemes to avoid local ‘pirates’.)

Another source of alarm for the travellers is the unstable political situation between Greece and Turkey. It is something the Bents have to face throughout their years spent travelling in the region. In April 1886, the European powers decreed that: ‘Since the Athenian Government’s answer to the common note of April 14/26 was not satisfactory to the Powers, the said Governments ordered the Commandants of the united marine squadrons to embargo the coasts of Greece for every ship under Greek flag. This embargo should be realised on the date of this communication. It should begin at Cap Maleas and finish at Cap Sounion, and from there till the border of Greece, including Euboea, as well as the entrance of the Corinthian Gulf at the west coast. Any ship under Greek flag that may try to violate this embargo, shall be captured.’ The embargo lasted a few weeks until the hostile Greek forces stood down, but the Bents were prevented from moving freely in Greek waters the while.

Manthaios Símos is now an indispensable member of the team and the Bents asked him to join them (with their tents he had been looking after) on Chíos. Of the other characters encountered on this tour there was the Turkish polymath and first director of the National Museum in Istanbul, Osman Hamdi Bey. Hamdi made several great discoveries in his own right, including the magnificent ‘Alexander’ sarcophagus. On Kálymnos Mabel is particularly keen to meet the young Greek wife of Theodore’s colleague from the British Museum, William Paton, himself an antiquarian of note: as was Henry Fanshawe Tozer, who encounters the Bents on Sámos. Tozer (in The Islands of the Aegean, 1890, p. 302) recalls their meeting at a temple site on Sámos: ‘The most important ruins are those of a temple, which have recently been brought to light by the indefatigable spade of Mr. Bent.’ (It was Tozer who thought that Edward Lear would like a copy of Bent’s Cyclades, presenting him with one in 1885. Lear writes: ‘Tozer of Oxford sends me a charming book…by Theodore Bent…all about the Cyclades. (Dearly beloved child let me announce to you that this word is pronounced ‘Sick Ladies,’ – however certain Britishers call it ‘Sigh-claides.’)…’ [letter to Chichester Fortescue, Lord Carlingford, 30 April 1885, San Remo]).

While Mabel is busy with her Chronicle, Theodore occupies himself with matters antiquarian. He wrote several letters from Constantinople to the British Museum and the Hellenic Society, most of which concern the new director of the Istanbul Museum, Hamdi Bey. From the Hôtel de Byzance on 17 February 1 he writes to Arthur Smith at the British Museum complaining about Hamdi’s intractability over some casts sought by London of the famous Budrum Lion; he tries to embroil the British Ambassador, Sir William White. These are portents of similar clouds looming for Theodore himself.

The couple’s itinerary this trip (1886) is: London – Marseilles – Sýros – Smyrna – Istanbul – Mitilíni – Smyrna – Chíos – Sámos – Pátmos (and the isles around, several times, depending on the winds) – Ikaría – Sámos – Kálymnos – Astypálea – Sámos – Ikaria – Ceşme – Chíos – Athens – Marseilles – Calais – London.

They arrive home again at the end of May. Theodore has a fever he thinks he contracted in the marshes of Sámos. It is a cautionary reminder of the risks to health present in the Mediterranean and further east. That spring there was cholera and death in Brindisi, Trieste, and, of course, Venice.

Tour 5 (1887 – From Istanbul and into the northern Aegean)

The Bents enjoyed their summer of 1886, having cruised along the Turkish coast that spring, visiting Mabel’s relatives in Ireland, including their connections in the County Carlow countryside at Bennekerry. The couple were seldom still. Theodore writes from Bennekerry to A. S. Murray at the British Museum, making first mention of a trip he has in mind up to the Thracian littoral. Frustrated in his attempts to excavate for the moment along the coast of Asia Minor, and Greece, too, being off limits in terms of his particular methods of working, Theodore’s 1887 plans are for an expedition to the northern Aegean. Spectacularly, Mabel begins her 1887 Chronicle atop a monastery in Metéora, central Greece. She is nursing Theodore who, again, is ill with a fever. (These ‘fevers’ seem to have begun in the unhealthy marshes of Gávrio, Ándros, in 1884, and to have reoccurred frequently: in ten years he will be dead as a consequence of them.)

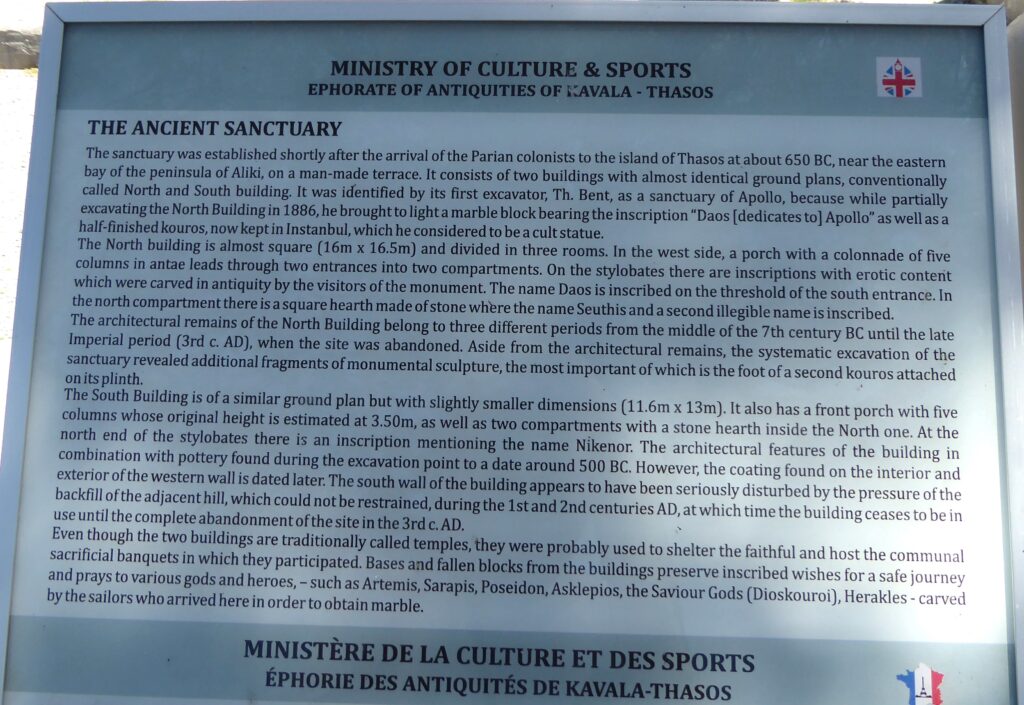

The tour begins with the party of travellers, including Manthaios Símos, on its way to the Turkish island of Thásos to dig, Theodore having received a grant of £50 from the Hellenic Society, and the backing of the British Museum so to do. In the end, Murray at the Museum needed prompting and Theodore resorted to some name-dropping. In October 1886, he wrote again to Russell Square asking for a reference he could forward to the diplomat Sir Villiers Lister, who, in turn, would take up his case with Sir Evelyn Baring in Egypt: as high as one could go. His request to Murray also contained a douceur: ‘At the council of the Hellenic Society I spoke about the mask which was without hesitation said to belong to me. Consequently I shall have pleasure in placing it at the discretion of the British Museum. Believe me, yours very truly, J. Theodore Bent’. (The mask in question is the excavator’s Samian find from earlier in the year; its Museum inventory number is 1886.1204.2.)

Theodore does manage to secure papers, of sorts, from the Turkish authorities. He hopes he will be allowed to remove his finds. He is mistaken. Back on Thásos Theodore finds over forty inscriptions, including an important decree. Several publications cover his important work on the island. E. L. Hicks commented extensively on the inscriptions for the Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 8, 1887, pp. 409–438).

Rich in classical references, Thásos was colonized by the Parians (8th century BC), who were the first to exploit the island’s gold resources. Theodore was keen to see for himself if there were similar treasures, if not precious minerals then at least beautiful marble sculptures to rival those found on nearby Samothráki – its famous ‘Winged Victory’ had already been stunning visitors to the Louvre for twenty-five years. Mabel and Theodore take a two-week detour to Samothráki to see the great site she was removed from in 1863. Another attraction for Theodore was the region’s Genoese associations. He was a student of the Italian state, whose fortifications can still be seen on Thásos.

Before they arrive in Thrace, however, the Bents make a detour to the fantastic cluster of monasteries known as the ‘rocks in the air’ (Metéora), reaching the region by rail from Vólos (having crossed first to Évia). In these pages we also have Mabel’s only record of the couple’s earlier trip, in 1882/3, to the great archaeological sites of Tiryns, Mycenae, and Delphi. It was these and other locations, which were in the process of continual excavation (Mycenae so famously by Schliemann in the 1870s), which partly inspired Theodore to focus his energies on his particular form of archaeological explorations thereafter.

From Vólos, the party cruises up the wonderful (then Turkish) coastline, with Mts Ossa and Olympus on their left (west), and Mt Áthos in view on their right (east), to Thessaloníki – one of the great, commercial Mediterranean cities. To reach their destination, Thásos, they follow the route of St Paul towards Kavála.

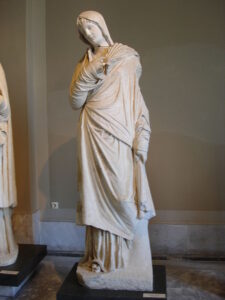

Immediately after their arrival on Thásos, Bent’s workmen start to uncover remarkable finds; they concentrate on three sites, two around the island’s capital and the other at Alykí (Aliki) on the south-east coast. Mabel’s favourite find, apart from her pet tortoise, ‘Thraki’, is a statue of Floueivia Vibia Sabina (died around AD 137), Empress and wife to Hadrian. Theodore finds a memorable inscription to her: ‘To their mother Phloueibia Sabina, the most worthy archpriestess of incomparable ancestors, the first and only lady who had ever received equal honours to those who were in the senate.’ The statute is of some artistic merit, executed around AD 215, but perhaps not quite as beautiful as Mabel would have us believe; her nose and hands are damaged. She featured as one of a group of figures adorning an impressive Roman arch. Theodore’s strategy is to use dynamite to help clear the site (Mabel reports that he is ‘busy overlooking blasting at the arch’), an approach he is to repeat elsewhere and which has damaged his own reputation ever since as an archaeologist. The whole assemblage of the arch is first reported in a letter he wrote to the British Museum (in an undated letter from Kavála), and then in several accounts, including the Athenaeum of June 1887 (p. 839).

The highlight of the Aliki excavations was the find of a large marble kouros figure (6th c. BC; neck to knee-cap = 1.34 m; round the shoulders = 1.480 m; round the waist 1.01 m). Mabel describes it briefly in her diary: “On Monday 2nd [May, 1887] there came 20 men; some civilly said they would go if not wanted but were all engaged at least for one day and afterwards we found the place so good we were glad to keep them. We think the place must be a Pantheon as we found inscriptions mentioning 9 gods or goddesses and Pegasus. We had a delightfully satisfactory week and found a headless, armless and below the knees legless colossal archaic statue and several other bits and many inscriptions.” (Mabel Bent Chronicles, Vol. 1, p.214, Oxford, 2006) Interestingly, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, has an early Apollo head from Thasos; although referred to as possibly from a sphinx, it is not known whether any research has been done to see if it fits the ‘Bent Kouros’!

Despite all of Theodore’s efforts to retain these marbles (including a request that the Foreign Office should send in a steamer to remove them from Thásos), the canny Hamdi Bey quietly had them shipped off to his museum in Istanbul. Theodore was enraged, resorting even to badger Sir Evelyn Baring, in effect the British ‘viceroy’ of Egypt. He similarly petitioned the British Ambassador at Istanbul, Sir William White.

In their issue of 23 November 1902, The New York Times (p. 5) has a strange piece erroneously reporting that Theodore Bent had discovered on the island the tomb of the suicide Cassius. Theodore and Mabel Bent did indeed make extensive excavations on the island between March and May 1887, but they did not discover Cassius’ final resting place (if Brutus indeed did take him there for burial), nor attempted to search for it; there is no reference to such a find in any of Bent’s publications, of course, nor in Mabel’s journals (and in any event, by 1902 Theodore had already been dead five years!). The enigma is solved by the fact that in the summer of 1902 the German Berliner Tageblatt reported on some Thasiote finds, and this was picked up by the English media, who casually referred in their copy to the work of Bent on the island some years previously; and the New York Times (we have a sort of ‘Chinese whispers’ here) in their turn carelessly printed a little fake news on 23 November 1902, i.e. that it was Theodore who had located the grave of the famous Roman general.

In addition to the “Bent Kouros” from Aliki (inv. 374) and the statue of Fl. Vibia Sabina (inv. 375), the Istanbul Archaeological Museum has two other Thasian finds confiscated from the Bents by Hamdi Bey: a decorated marble relief (inv. 376), and a head of Hermes (inv. 409).

The couple’s itinerary for their 1887 season is: London – Paris – Marseilles – Sýros – Athens – Évia – Vólos – Tríkala – Metéora – Vólos – Skiáthos – Thessaloníki – Kavála – Philippi – Thásos – Alexandhroúpoli – Samothráki – Thásos – Kavála – Thessaloníki – Üsküb/Skopje – Vranya/Vrange – Belgrade – Paris – London.

Folded in the pages of her Chronicle is a letter from the unhappy wife of a minor functionary in Skopje. She implores Mabel to visit: ‘Monday morning. My dear Madam, You would really do me a great favour if you would spend an hour or two with me today. Ours is rather a rough kind of home, but I can offer you a cup of tea. I think if you only knew how hard it is for an educated woman to be in exile at such a place as Üsküb, without either congenial society or habitual surroundings, you would come out of charity. May I fetch you about 4? With compliments to your husband, Faithfully yours, Florence K. Berger.’

Tour 6 (1888 – From Istanbul and along the Turkish coast)

Not a couple to give in easily, Mabel and Theodore spend a good deal of their summer and autumn of 1887 trying to drum up enough support to have the marbles from Thásos rescued from the Turkish authorities and saved for London. Letters exist from a series of addresses in Herefordshire, and Theodore’s comfortable seat of Sutton Hall, near Macclesfield, to Smith and Murray at the British Museum: ‘We have indeed been unfortunate about our treasure trove but I have hopes still. I sent to Mr. Murray a copy of two letters which recognize the fact that I had permission in Thasos both to dig and to remove. These I fancy had not reached Sir W[illiam] White when you passed through Constantinople. Seriously, the great point to me is prospective. Thasos is wonderfully rich and I have some excellent points for future work and … I am confident we could produce some excellent results.’

In January 1888, Theodore did receive a further grant of £50 from the Hellenic Society to return to Thásos to excavate, and the couple duly left for Istanbul. Unsurprisingly, the implacable Hamdi Bey refused him leave to carry out further investigations on the island. Despite various appeals to the Ambassador, Sir William White, he and Mabel were forced to change their plans.

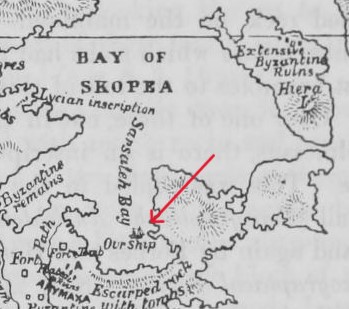

Theodore may well have been expecting this. In the Classical Review of May 1889 (Vol. 3, No. 5, pp. 234-237), his friend E.L. Hicks reveals that while Bent was first digging on Thásos in 1887 he had employed a local man to ‘to make some excavations in the neighbourhood of Syme’ (way down the Turkish coast, north of Rhodes) on his behalf. Obviously satisfied with the results, the couple, after an excursion to Bursa to see the fabled Green Mosque, decided to return to Cycladic Sýros (where they chartered the yacht Evangelistria under Greek papers) and embark on this fall-back plan.

At Sýros, in Mabel’s words, ‘Theodore at once took to visiting ships to put into practice our plan of chartering a ship and becoming pirates and taking workmen to “ravage the coasts of Asia Minor”. Everyone says it is better to dig first and let them say Kismet after, than to ask leave of the Turks and have them spying there.’ The couple also meet up here with Manthaios Símos, who has sailed up from his home on Anáfi , close to Santoríni.

The couple’s investigations along the Asia Minor littoral (in particular the coastline opposite the island of Rhodes) were extremely fruitful and some of Theodore’s marbles from this expedition are now in London. He briefly wrote up his discoveries of ancient Loryma, Lydae, and Myra for the Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 9, 1888), but a lengthier account was provided by E. L. Hicks (Vol. 10, 1889), including transcriptions of over forty inscriptions and passages of text from Theodore’s own notebooks.

The couple obviously found their journey home last year by train more satisfactory. This year they opted for a more northerly rail route, via Russia and Poland and down into Germany. Their plundered marbles from Turkey went incognito, and under Turkish documentation, via ship to the British Museum.

Mabel’s itinerary for 1888 is: London – Marseilles – Sýros – Smyrna – Istanbul – Broussa – Istanbul – Sýros – along the Asia Minor coast as far as Kastellórizo – Pátmos – Sýros – Smy rna – Istanbul – Scutari – Adrianople – Plovdiv – Istanbul – Nicea– Istanbul – Odessa – Berlin – London.

Tour 7 (1890 – Further researches along the Turkish coast and into Armenia)

“Mr. and Mrs. Bent had conferred by their expedition another of the annual benefits which they had been conferring upon the British Museum in particular, and upon Greek archaeology in general.” Cecil Smith of the British Museum following Bent’s presentation of their 1890 expedition results at the RGS meeting, 30 June 1890 at London University. (Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, n.s. v.12 1890, p. 460)

To avoid the problems of excavating in Greece or Turkey without adequate documentation, Mabel and Theodore spent the 1889 season on an epic trek that takes them from a tour of Bahrein and then up through Persia, landing at Basra from Karachi. This gruelling trip takes up the three notebooks comprising Mabel’s sixth Chronicle. Theodore is developing his personal theories on the origins and influence of the Phoenicians, en route, and publishes a short paper in the Classical Review in November 1889 (‘The Ancient Home of the Phoenicians’). Two other articles, more topical, are published subsequently – ‘The Bahrein Islands, in the Persian Gulf’ (Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, 1890), and ‘Under British Protection: Impressions of Muscat, Bunder Abbas & Bahrain’ (for an 1893 issue of the Fortnightly Review).

It is this, the couple’s first lengthy expedition in a region new to them, and the fact that they can freely excavate in lands where British interests are more favoured, that give Theodore and Mabel the appetite for exploring in a south-easterly arc, taking them far beyond Greece and Turkey, for the remainder of their travels together …but one.

Mabel’s seventh Chronicle finds the team (again joined by Manthaios Símos, who was offered, but declined, the extremely onerous Persian campaign) in the far south-east of Turkey, in ancient Cilicia, about as far as Theodore can get from the suspicious eye of Hamdi Bey and his archaeological service officials. Even then, in this remote sweep of the Ottoman Empire, washed by the eastern Mediterranean as far as the shores of Crusader lands, Theodore runs into trouble with the local authorities as he negligently delves through Byzantine monuments in search of traces of the times of Alexander the Great.

The Chronicle even ends with Mabel copying a sharp, but polite, rebuke arriving from an official of the Adana consulate (9 April 1890) into the last page of her notebook:

‘Dear Mr. Bent, The Governor General, having received information that you are revisiting the same places you had already visited some time ago on the road to Selefka, and that you are taking photos or plans of the various places, requests me to make you acquainted with the fact that the taking of photos or plans of the places is not allowed without the special permission of the government. His Excellency therefore requests me to invite you in a very polite manner to discontinue from taking photos, etc., as above mentioned. Complying with His Excellency’s request, I ask leave to add that it would be better if you came back to Mersina in order to avoid any possible troubles with subaltern officials. The best way to continue your scientific investigations unmolested is, in my opinion, to request His Excellency, Sir William White, to obtain for you from the ministry at Constantinople the required permission. N. J. Christmann’

What drove the Bents to Turkey again in 1890 was the challenge of lost classical sites. The British pioneer of the region was Edwin John Davis, whose Life in Asiatic Turkey (London, 1879) remains in the bibliographies, and in Athens Mabel sees a ‘circular from the Hellenic Society requesting us to subscribe to an Expedition of exploration in Cilicia, to be headed by Mr. Ramsay [the regional specialist, Sir William Mitchell Ramsay] to start in June. “It is most desirable that the site of Olba should be discovered and identified.” So I declared that we would look for Olba too.’ Certainly Theodore would have also been up for the challenge.

Olba was found in western Cilicia. This region, described so resonantly by Strabo, lies on the southern coast of modern-day Turkey, and was divided in ancient times into two halves: to the west, Cilicia Trachea (‘rough’ or ‘rugged’), a mountainous region bounded by Mount Taurus; and to the east, Cilicia Pedias (‘flat’), with its rivers and fertile plans. Historically, the importance of Cilicia lay in its position on the great highway to the east that ran down from the Anatolian plateau to Tarsus and on through Syria into Asia. This highway passed through a narrow rocky gorge called the ‘Cilician Gate’, and hence the strategic importance of Cilicia when invaded by Alexander and Darius.

The Bents and all their luggage arrive in the port of Mersin and make their way the short distance to Tarsus, the home of St Paul. Their explorations were divided into three phases: a reconnoitre along the coastal region, during which Theodore located the site of Hierapolis; a trip inland to see the Nestorian and Armenian churches around modern Kozan; and then up the Lamas valley, where they do, indeed, discover Olbian territory. Theodore’s unscientific approach to excavating around the famous ‘Caves of Heaven and Hell’ has provided another occasion for critics to deplore his methods.

Be that as it may, he did return with much evidence of the region’s historical past and his reports are to be found in several papers, including ‘Recent discoveries in eastern Cilicia’ for the JHS (Vol. 11, 1890) and ‘A Journey in Cilicia Tracheia’, also for the JHS (Vol. 12, 1891). The latter were scholarly reports but he also presented an entertaining and readable paper to the evening meeting of the Royal Geographical Society of 30 June 1890 entitled ‘Explorations in Cilicia Tracheia’. It was subsequently published in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (London, 1890). Keen to tell academic London of his discovery of Olba, he writes to Arthur Smith (a future director of the British School at Athens) from Mersin. Smith is sceptical, and writes as much for a piece in the Classical Review of April 1890.

The value of Theodore’s work in the area is (on the whole) supported by the researchers W.M. Ramsay and D.G. Hogarth in their visit to Olba and Korykos soon after the Bents. The ‘Athenaeum’ of July 26 and Aug 16, 1890 contains their early report: “On our way from Selef’keh to the north we visited some of Mr. Bent’s brilliant discoveries of this year. We went first to Olba, the ruins of which are among the most interesting in Asia Minor, and fully justify Mr. Bent’s description in the ‘Athenaeum’ of June 7 (see pp. 351-4); but the temple, though imposing to a distant view, is a great disappointment, being coarse and bad in style without any trace of archaic character. We must express our high admiration of the care and thoroughness with which Mr. Bent examined this and other places that we visited. The way in which he concentrated his work on a small district may be recommended to all archaeological travellers, and his splendid discoveries in a country recently visited by such explorers as Langlois, Duchesne, Sterrett, etc., prove that this method is the one most likely to be successful.”

(For more background, see our separate post on Olba, etc.)

After his not inconsiderable discoveries in ‘Rough Cilicia’ Theodore never excavates in classical Greece or Turkey again – going off in search of the influences of the ancient Greeks and Phoenicians in more distant lands – but it was a typically bravura farewell to the region that had captivated the Bents for nearly a decade.

In Athens, the Bents spend time with Ernest Gardner and Charles Waldstein, directors of the British and American Schools respectively, and other archaeologists, including the great Heinrich Schliemann. They attend Court and renew acquaintance with old Greek friends, many now in positions of power. They have time, too, to take in a performance of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine. In this Athenian interlude, Mabel adds a throwaway remark, ‘I need not say the Acropolis and Museums were not neglected’, a line echoed in her last entry from Athens in just seven years, when, alone, she revisits the Greek capital and never begins another Chronicle.

Outward bound, Mabel celebrates her forty-fourth birthday, 28 January 1890, on board the ‘French M.M. steamer for Mersina’. Their 1890 itinerary being: London – Lucerne – Milan – Rimini – San Marino – Ancona – Corfu – Pátras – Athens – Smyrna – Mersin – Tarsus and the entire region of ancient Cilicia – Smyrna – Thessaloníki – [Athens?] – Marseilles – Paris – London.

Two further visits to Greece: 1896 & 1898

1896

After their 1890 expedition to Cilicia, the Bents never undertook further researches in Greece or Turkey, preferring to concentrate on Africa and the Middle East in a series of extended, and often gruelling, treks.

Two of Mabel’s later Chronicles include short references to Greece. On 2 December 1895, Mabel and Theodore set off to explore along the Sudanese coast, moving down through Egypt; they meet up with Manthaios in Port Said, and again he acts as cook and assistant for the length of the trip (he will have travelled from the small Cycladic island of Anáfi, via Sýros).

By the end of March 1896, the couple are ready to return and leave Alexandria to spend a few days in Athens before the journey home. Their stay repeats the familiar pattern of visits to friends and archaeologists – Theodore is even recruited by the British School to supervise a small dig below the Olympieion (no notebook seems to have been archived). They were endeavouring to locate the Kynosarges (the athletes’ gymnasium), an apposite objective, as the Bents’ visit coincided with the first staging of the modern Olympic Games (held between Monday 6 and Wednesday 15 April 1896). A very modest affair by the standards of the Athenian games of 2004, the events were limited to athletics, cycling, fencing, gymnastics, shooting, swimming, tennis, weight-lifting, and wrestling. It seems that the contests were more or less open to any gentleman amateur who happened to be in Athens – it is surprising that Theodore did not try and enter himself for something.

The Bents’ five-month itinerary for 1896 was: London – Basle – Milan – Venice – Port Said – Cairo – the Sudan coast – Cairo – Alexandria – Athens – Milan – London.

1898

The last few references to Greece in Mabel’s Chronicles appear in her 1898 volume. She begins in melancholy mood, heading her notebook ‘A lonely useless journey’. After nearly twenty years of travels with Theodore, she finds herself alone, her husband having died of ‘malarial complications’ a few days after returning to London in May 1897.

‘To the great grief of his friends, Mr. Theodore Bent died last week in the prime of life…kind, genial, and unassuming, who never sought for selfish advantage…He and his accomplished wife made every winter an expedition to some out-of-the-way spot for archaeological research.’ (The Athenaeum, January–June 1897, p. 657)

By now Mabel was so used to spending her winters abroad, however, she signs up for a solo trip to Egypt. But it is not a success and prolonged travels lose their attraction for her. Understandably, her notes are downbeat and she has little enthusiasm for sharing the monuments along the Nile with groups of happier visitors –‘It was very strange the first day riding alone and unknown and unknowing in such a troop’. By Friday 11 February she has had enough and leaves Alexandria for Athens.

After the loneliness of Egypt, Mabel enjoys Athens and the area, seeing again their old friends at the British School. There is a visit to the astonishing Byzantine mosaics at Daphní. She is shown over the Acropolis by the famous German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld, and it is appropriate that the last words in her Chronicles reflect the Bents’ fascination with the classical past – ‘Of course I have not neglected the antiquities either’.

Mabel’s 1898 itinerary was: London – Paris – Marseilles – Brindisi – Port Said – Karnak – Luxor – Abu Simbel – Luxor – Thebes – Alexandria – Athens – London (by an unspecified route).