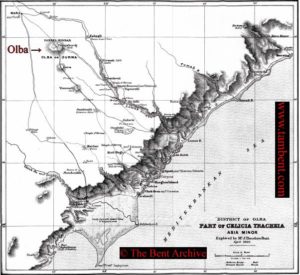

Map: ‘Part of Cilicia Tracheia’. Theodore Bent’s own map of their routes in the area of Olba.

Map: ‘Part of Cilicia Tracheia’. Theodore Bent’s own map of their routes in the area of Olba.

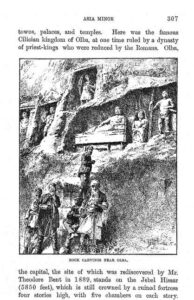

“The ruins of Olba, among the most extensive and remarkable in Asia Minor, were discovered in 1890 by Mr. J. Theodore Bent. But three years before another English traveller had caught a distant view of its battlements and towers outlined against the sky like a city of enchantment or dreams.” (Fraser, ‘The Golden Bough’, Vol 5, 151ff). [Actually, James, it may be claimed to be Mabel!]

Constitution Square, in the era of the Bents, and their base in Athens. Their hotel was located here.

Constitution Square, in the era of the Bents, and their base in Athens. Their hotel was located here.

It is early 1890; we will reach Olba later. But for the moment Mabel and Theodore Bent are in Athens, having arrived on 25th January from Patras – their ship the NGI ‘Rubattino’ from Ancona. They meet their dragoman, the long-suffering Anafiote, Matthew Simos, and, before finalising their plans for the season’s explorations, settle comfortably into the Hôtel des Étrangers in Constitution Square, the very heart of bustling, late-19th century Greece.

Theodore had been ten years an ‘archaeologist’ and was at last something of a name (and something of a thorn in his peers’ sides too, as we shall see). By 1889, the archaeologist had ‘excavated’ in the Cyclades, Dodecanese, Thasos, down along the Turkish littoral, and way East, to the ‘mounds of ‘Ali’ in Bahrain. But his 1890 season found him rather aimless in Attica, with his wife, dragoman, and all his bundles of exploratory gear. Where should they go? The answer was ‘Olba’ and (luck being really everything) 1890 was to see Bent’s career soar: within 12 months he had been sponsored by Rhodes (the man, not the island – although he visited there in 1885) to dig for him at ‘Great Zimbabwe’ and this truly made him a celebrity (again, with notoriety). He was only to live seven years more, alas, but in those few years he and Mabel rode around the Yemen, Ethiopia, Sudan, and back to Yemen. East of Aden he aggravated the malaria he first contracted on Andros in the winter of 1883/4, the finale of which was an early death, at 45. But let’s cut back to Athens in the very early spring of 1890.

The Bents had a busy week in the capital, their arrival previously ‘announced in the papers’, as Mabel recalls in her ‘Chronicle’: “Theodore arrived with the influenza, so did not go out on the Sunday [Jan 26]. I went to church and then drove to the British School of Archaeology to call on the Ernest Gardners. We dined with the Gardners. We made a party to drive up with Sir John Conway and Mr. Bourchier and there were 4 students. We also lunched with the Schliemanns. There were the Gardners and Mr. Kavadias of the Museum and old Mr. Rangabe, a great poet and authority on the language and literature. I was very glad to meet him and he was delightfully surprised that I could speak Greek. Dr. Waldstein, the Rector of the American School, was there too and the daughter Andromache and little son Agamemnon. Afterwards we went to the Pireaus to see the Consul and Mrs. de Puy. We knew them at Volo and liked them. They were not surprised to see us and only wondered at our not coming before as our coming has so long been announced in the papers. I need not say the Acropolis and Museums were not neglected.” (‘Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent‘, Vol 1, 271ff, Archaeopress, 2006)

Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (Rakgabis)(1809–1892), Greek man of letters, poet and statesman.

Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (Rakgabis)(1809–1892), Greek man of letters, poet and statesman.

Their brief, hectic stay is a sequence of lunches, teas, and dinners. Around all these tables we have notable figures, so let’s add some notes: The Schliemanns require no introductions; Ernest Gardner (his wife was Mary Wilson) was director of the British School until 1895.

James David Bourchier (1850–1920). Irish journalist and political activist.

James David Bourchier (1850–1920). Irish journalist and political activist.

Other guests were the colourful James Bourchier, Balkan correspondent of the Times, Irish, he would have been doubly of interest to Mabel (“The passion… for this ex-Eton master and Times correspondent earned him [in the Balkans] a position… similar, in a lesser degree, to that of Byron in Greece.” With his muse Nadejda, Patrick Leigh Fermor passes by his memorial near Rila Monastery on his great walk – The Broken Road, 2014, p.15).

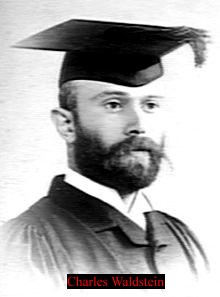

Panayiotis Kavvadias went on to become General Inspector of Antiquities and a founder member of the Academy of Athens; very disrespectfully (and were they flirting? The chances are he was teasing Mabel about her Greek!) ‘old Mr. Rangabe’ was Alexandros Rizos Rangavis, the man of letters, poet and statesman; Charles Waldstein (later Sir Charles), director of the American School until 1893, was an Anglo-American archaeologist with a distinguished academic record; his wife was Florence Einstein and it seems they indeed had a son and a daughter, but where Mabel gets Agamemnon and Andromache from is a mystery (Wikipedia names the boy Henry), again, was Mabel being teased?

Charles Waldstein (1856–1927), director of the American School until 1893.

Charles Waldstein (1856–1927), director of the American School until 1893.

Anyway, remember Olba? It seems that during this busy Athenian week the Bents were still without a primary research target and focus for their fieldwork. They were back in the Eastern Mediterranean for their customary three- of four-month exploratory season (the rest of the year usually spent back in the UK ‘writing up’), but opportunities now for excavating were limited – Greece and Turkey frowning upon adventurers and freelancers, such as Theodore and Mabel.

One area of possibility was to make again for out-of-the-way Turkish waters – they had been as far as Kastellorizo in 1888 – but where this time? By chance in Athens Mabel makes a discovery, revealed later in her diary: “In Athens we received a circular from the Hellenic Society requesting us to subscribe to an Expedition of exploration in Cilicia, to be headed by Mr. Ramsay and to start in June. ‘It is most desirable that the site of Olba should be discovered and identified.’ So I declared that we would look for Olba too.” Typical Mabel this. (‘Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent’, Vol 1, 274, Archaeopress, 2006)

Olba lay undiscovered somewhere in western Cilicia. This region, described wondrously by Strabo (14.5), lies on the southern coast of Turkey, and was divided in ancient times into two halves: to the west, Cilicia Trachea (‘rough’ or ‘rugged’), a mountainous region bounded by Mount Taurus; and to the east, Cilicia Pedias (‘flat’), with its rivers and fertile plans. Historically, the importance of Cilicia lay in its position on the great highway to the east that ran down from the Anatolian plateau, to Tarsus, and on through Syria into Asia. (This highway passed through a narrow rocky gorge called the ‘Cilician Gate’, and hence the strategic importance of Cilicia when invaded by Alexander and Darius.) The British pioneer of the region was Edwin John Davis, whose ‘Life in Asiatic Turkey’ (London 1879) remains in the bibliographies, but ten years later it was William Mitchell Ramsay (1851–1939), the Scottish archaeologist and New Testament scholar, who led the field west of Mersin. The bit very much between her teeth in Athens in the late winter of 1890, Mabel was now determined to get to Olba first; and she did of course – the trip will be detailed in a further post.

Sir William Mitchell Ramsay (1851–1939). Scottish archaeologist.

Sir William Mitchell Ramsay (1851–1939). Scottish archaeologist.

Ramsay, aided and abetted by a young David Hogarth (the young man referred to by Fraser in the opening quotation) were gracious in defeat (in print at least), but headed the force of establishment scholars who were to snipe at Bent from their trenches from now on. Bent, self-trained and cavalier, was driven by his own ideas and paid little if no heed to context, or seemed to have much interest in understanding the broadest evidence offered by his sites – but these were still early days for ‘archaeologists’.

An intrepid explorer and antiquarian the, yes, but calling himself an ‘archaeologist’ was too much for too many. For examples of criticism you need look no further than Ramsay and Hogarth referred to above. The former writes to the editor of the ‘Journal of Hellenic Studies’ in May 1890, frustrated that Theodore’s expedition to Olba has angered the local Turkish authorities: ‘Now however it is reported to me that the officials are far stricter than ever before, and since Bent has been about our track, things will be much worse’. And again in January 1891 (when angry with the JHS for not allowing Theodore more of Mabel’s photographs in his paper for them) : ‘It is a scandal to hear how they [the team at the JHS] have treated Bent. If they refused his paper I would understand it, for he is not a scholar & makes some serious faults. But the things he found at Olba are of high interest, & illustrations are just what would carry through with such a rough paper.’ (source: SPHS, George A Macmillan Archive)

David George Hogarth (1862–1927) British archaeologist, later Arab specialist

David George Hogarth (1862–1927) British archaeologist, later Arab specialist

David Hogarth seems to have nurtured a grudge against Theodore for decades – perhaps never forgiving the latter for beating him to Olba. He got his chance to vent his spleen at last in print in 1900, in a review for ‘Man’ of Mabel’s work, compiled in the most difficult of circum-stances, of on Theodore’s researches published as ‘Southern Arabia’ (London 1900). The book is now regarded as a classic of course, but Hogarth puts the desert boot in: ‘As it is, the [Bents] apparently had not realized what it was essential to observe and record, and what, on the other hand, is commonplace of all Arabian travel; and the trivialities of caravan life, already rendered more than familiar by Burckhardt, Palgrave, and Doughty, to mention only the greatest names, fill two-thirds of the account, suggesting in every paragraph unfortunate comparisons with the deeper knowledge, the truer sympathy, and the sense of style that inspired those brilliant narratives.’ (Review 23 in ‘Man’, Vol. 1, 1901, 29-30; signed H, and presumably D.G. Hogarth)

It doesn’t end there, this Hogarth later doggedly continues in his own Arabian monograph; here he refers to Theodore’s altercation with the Aden authorities’ inexplicable obstructions (one suspects Hogarth and his spy-masters) in the winter of 1893: ‘The governors of Aden, therefore, have been fully justified in refusing to exert pressure on behalf of certain would-be exploring parties whose qualifications were not such as to promise the best scientific results; and when countenance was given at last in 1893, to the archaeologist Leo Hirsch, it was because he was known to be a profound Arabic scholar, expert in the law of Islam, who would conduct himself tactfully. When, shortly after, it was given also to Theodore Bent, despite his lack of qualification, it was because his party included an Indian Moslem surveyor and his staff, who might be expected to make a solid contribution to geography.’ (‘The Penetration of Arabia‘, 1904, London, p. 216)

Hogarth is unforgiven, although he appears kind enough to Mabel in February 1898, the year after Theodore’s death: ‘I lunched at the English School with the Ho-garths… Mr. Hogarth took me to the Akropolis.’ (‘Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent’, Vol 1: 330, Archaeo-press, 2006). But at least Theodore takes the glory in John Fraser’s towering epic!

A subsequent post will take us to Cilicia and Olba, and the Bents’ very significant finds there.

Captions: Map: ‘Part of Cilicia Tracheia’. Theodore Bent’s own map of their routes in the area. Originally published in ‘Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society’, New Series, Vol. 12, No. 8, August 1890; Constitution Square, in the era of the Bents, and their base in Athens. Their hotel was located here (image: Martin Baldwin-Edwards); Sir William Mitchell Ramsay (1851–1939). Scottish archaeologist; by his death he had become the foremost authority of his day on the history of Asia Minor. It was Ramsay who prompted the Bents to seek for Olba in 1890, beating him to the site by a matter of months (Image: Wikipedia); David George Hogarth (1862–1927) British archaeologist, later Arab specialist, and Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford from 1909 to 1927. Ten years Bent’s junior he was an unkind, waspish and harsh critic; Bent beat him to the discovery of Olba by a few months, and probably never forgave him – doubly galling as Hogarth had espied the site from a distance some time before but was forced to abandon his search (Image: Wikipedia); Charles Waldstein (later Sir Charles) (1856–1927), director of the American School until 1893 (Image: Wikipedia); Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (Rakgabis)(1809–1892), Greek man of letters, poet and statesman. (Image: Wikipedia); James David Bourchier (1850–1920). Irish journalist and political activist. He worked for ‘The Times’ as the newspaper’s Balkan correspondent (Image: Wikipedia).

[We are most grateful to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies for allowing us to reprint extracts from W. M. Ramsay’s letters. The Bents were early members of the SPHS (1880s) and frequent contributors and speakers at events. Mabel’s diaries are in their archives]