FOR famous travellers, the Bents preferred to be homebirds come Christmas time, swapping solar topees for deerstalkers, and leaving their London base near Marble Arch for family visits to Ireland and elsewhere. Of their nearly 20 years of explorations (in the 1880s and ’90s), they were only out of the country on 25 December, or so the archives indicate, for 1882 (Chios – for Orthodox Christmas), 1883 (Naxos), 1891 (steaming home from Cape Town), 1893 (Wadi Hadramaut), 1894 (Dhofar), 1895 (Suez), and 1896 (the island of Sokotra).

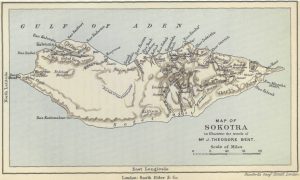

Map of ‘Sokotra’. From the Bents’ Southern Arabia (1900), facing page 342. Private collection.

Map of ‘Sokotra’. From the Bents’ Southern Arabia (1900), facing page 342. Private collection.

And Christmas 1896, on this remote island, was to be the last the couple shared together. Out of respect, perhaps, for the land and people they were amongst, there were to be no festivities – this might explain why Theodore was out of sorts! [But at least we are spared Mabel’s cracker ‘mottos’, examples of which we have from Christmas 1895, when the Bents were in Suez. ‘I have made some crackers to surprise my companions at dessert, and I think they would be much better liked afloat than ashore, so I am sorry to dine on land. Of course, no mottos were to be had so I was obliged to manufacture some. Mr. Smyth, having been proved to possess only 3 rusty needles, is to have a needle-book and his motto is: ‘Cheer up! Mr. Smyth, and try to be blyth [sic]; though your clothes may be rent, says your friend Mabel Bent.’ Mr. Cholmley, a box of Ink Pellets. ‘Ever be good news by Alfred Cholmley sent, in ink of blackest hue’s the wish of Mabel Bent.’ Theodore a knife and fork and, ‘Good appetite to Theodore! May he ne’er need to wish for more than may be upon his table, is the hope of his wife Mabel.’]

By all accounts the couple spent several happy weeks on Sokotra, with its landscapes and flora making it something of a paradise, before their hellish experiences east of Aden – which led to Theodore’s early death aged 45.

The Bents made no great archaeological finds on the island, but Theodore wrote that ‘Caves in the limestone rocks have been filled with human bones from which the flesh had previously decayed. These caves were then walled up and left as charnel-houses, after the fashion still observed in the Eastern Christian Church. Amongst the bones we found carved wooden objects which looked as if they had originally served as crosses to mark the tombs…’ (The Island of Sokotra. ‘The Nineteenth Century’, 1897, Vol. 41 (244) (Jun): 978) Theodore gave (or sold) three of these wooden items to the anthropologist Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917). Tylor was Oxford professor of anthropology, and keeper of the university museum. His wife Anna presented the Bents’ Sokotran artefacts to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford in 1917 (1917.53.670-2). The Bents missed them, but recent excavations at the nearby Hoq cave have revealed votive remains thought to date from the 3rd century AD. (Soqotra Karst Project, http://www.friendsofsoqotra.org/index.htm)

But we can join Mabel at camp at ‘Kalenzia’ [Qalansiyah, Suquṭrā], a few days before Christmas 1896. The couple are busy administering to locals, collecting specimens and preparing for a trip to the interior:

‘Tuesday 22nd [December 1896]. Here we still are at Kalenzia. I did not venture to spell this name till I had heard it pronounced, as it is spelt in so many ways. The name of the island is Sokotra. We have been continuing our doctors’ work. One old lady with a skin affection was prescribed a preliminary washing with soap, but I was informed that in the whole of this island there is not such a thing, so of course it had to be given as a medicine. The Butterfly, Botanical, Shell, and Beetle collections have been started. We have not for years enjoyed such peace and safety. The people are most pleasant and do not worry us a bit by coming round our tents. We can walk about alone all over the place and yesterday Theodore and I went a long distance and found some inscriptions on a smooth rock, also a little hamlet, very clean (Haida), as is Kalenzia.

We sat down on the ground and were interested looking at the party we were amongst, one or 2 men, the mistress and 2 servants and slaves. The latter were spinning. They were dressed in dark blue with a kind of little grey and black goats’ hair carpet, woven in little looms a foot wide, which they wrap round as petticoats. They wore bead necklaces. Their mistress was much smarter. She had silver bracelets and many glass armlets and a pretty silver-gilt necklace and earrings, and a turkey-red dress made like those in the Hadramaut, but longer. The front came to the calf of the leg and the train would have been fully a yard on the ground had she not held it up. All the women wear their hair cut in a straight, short fringe and the better class paint with turmeric. Yesterday a most important looking old man came from the Sultan with a civil letter. He tried to persuade us to go most of the way to Tamarida by sea, but of course we refused. We are to have 15 camels and to pay 3 reals each for the journey, i.e. M. T. dollars 25 at 2 rupees each (2/6) and they are promised to be here in 3 days.

‘Christmas Eve, Thursday [24th December 1896]. We shall have been here a week this evening. The camels are roving round and it is said that the baggage shall be bound in bundles this evening and that we shall start tomorrow after prayers – even a little way. Yesterday we had a delightful day. We started after breakfast with luncheon, gun, butterfly net, photography, shell box, beetle box and flower basket. We went through the village and along the tongue of shingle which separates the freshwater lagoon from the sea and which we call Shark Parade, because there are so many of these monsters drying there. They all have their back fins and tails cut off and their spines are nearly as thick as my wrists. We then struck inland, passing through a village called Ghises, under the mountainside, and then climbed up, saw our first Dragon tree (a mistake. It was Adenia. Dragon’s blood grows 800 feet up the hills) and I took some photos of very curious trees. We lunched under some palms near a marshy and pretty stream and got back in time for tea and to attend to many patients, and this morning we have had much of the same work.

‘From Yehàzahaz, looking over the

‘From Yehàzahaz, looking over the

pass toward Adahan, Sokotra.’ Detail of a

watercolour by Theodore Bent; from Mabel

Bent’s paper in The Geographical Journal,

‘The Island of Sokotra (Read at the Meeting

of the British Association, Bristol, 1898)’. The

Scottish Geographical Magazine, Vol. 14

(12), 629-36. Private collection.

‘Christmas Day [Friday 25th December 1896]. A cloudy morning. Soon after breakfast, with the usual patients, a whole crowd came, headed by Ali, the chief personage, and the mollah. They roared and shouted and said we must have 25 camels, 4 only to be ridden, but we said we could not possibly ride without luggage to sit on. As a mater of fact 10 could take us. After a great row, fearing not to get away, we consented to have as many as they liked and would pay what the Sultan wished. Then Ali and the mollah came into the tent with a small bit of paper they picked up and wished him [Theodore] to write a contract with them in a very authoritative way. I was at the tent door and had to clear out in a hurry as out stormed T, giving good pushes to the two, telling them they were wicked men and he should take them prisoners to Aden. He then tore the paper into even smaller bits and flung it in their faces (the wind serving admirably).

‘They all apologized and soon left in a flock and sat down in a ring 100 yards off. Then someone came and said 16 camels, and then another came and said 18. ‘As you like,’ said we. They wanted T to write. ‘No,’ he said, ‘but if they wish I will write all their names down to show in Aden.’ This was declined. Now they are all here again, quite friendly. Mr. Bennett [a young Oxford scholar who joined the Bents at his own expense; see further in this article], to whom all these scenes are new, is away getting some wild duck. I think it must be a good thing for him to have our experience to fall back upon. It seems to me we are always saying one side of a Catechism on Ethnography and Botany, with Hints to Travellers and lessons in the Greek and Arabic Languages combined. His thirst for knowledge is great and ceaseless.

‘We have seen very little new to us here besides the little chicken houses made of a turtle shell with the earth scooped from under it. We have everything tied up in bundles by 11 and then had to sit till about 3 before the camels came. I never saw camels better fitted out before than these. We have had such different experiences. Our first camel riding was in the Island of Bahrein [1889], where we had splendid silver saddles on beautiful riding camels. Next the Hadramaut journey where the camels had small packsaddles and a good many rags to pad them and ropes with sticks. In Dhofar they came naked and we had to find all, even the nose ropes. The baggage was most hard to manage. In the E. Soudan they had good saddles, and many riding saddles but no sticks and used our ropes, of which we have a sack. Here they have excellent mats and pads, little packsaddles and then mats made of sacking, quilted with strong twine and sewn over at the edges very neatly. Sticks with excellent ropes, and, what is best of all, very strong matting bags, quilted with ropes, in which they tie up all the baggage to its great benefit. Their way of pronouncing the Persian ‘juval’ is ‘zoual’. We came 2 hours or so to the mouth of a valley. Iséleh.

‘December 26th Saturday [1896]. Started about 7 without any difficulty. The men seemed anxious to get on. The Sheikh sent by the Sultan is with us – a friendly old man. We continued our way till we had to dismount when the mountains closed in and we walked over a pass. We trotted wherever the road was smooth enough. Of course, when I speak of road, it is only a track. There were little bushes and a good deal of fine grass and some small trees. The [Adenia] trees in full bloom were lovely. The flower is very like in size and colour to pink oleander. We stopped at some water and filled some water-skins and then, about 1, stopped in a hollow basin, often filled with water no doubt but there is none now. Here the Arabs proposed to eat and unloaded the camels, so we decided to stay, as T had had a fall that had knocked him up a bit. First they said we should go to water quite close, but when T said we would send a camel they said it was a long way. What little water we got for our evening wash we had to save till morning, but we had tremendous rain in the night and I am afraid our bread and other things will prove to have suffered, as no preparations for rain had been made. ‘We are making a latish start to give things a chance to dry up. The place is called Lim Ditarr.

‘[Sunday] December 27th [1896]. We stopped halfway at a place with very salt water called Día. Here we lunched and the camels drank at the well. There were no houses. Near sunset we reached Eriosh, also an uninhabited place. There is about 1⁄4 mile of quite flat rock, partly covered by mud, dried. There a great many cuttings of feet of all sizes, of men as well as animals, some Himyaritic letters and other signs. Mr. Wellsted says much labour must have been expended in cutting in such very hard stone, but I could cut deeply with the first pebble I could pick up. I look on them as scribbles. We stayed 2 nights. It was too awfully windy to open our shady door.’

[All extract from ‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent Volume III: Southern Arabia and Persia’ (Archaeopress, 2010), pages 288-92]

Ernest Bennett subsequently wrote a piece for Longman’s Magazine (1897), which is touching for one its footnotes; the author writes: “Since these words were written Mr. Theodore Bent, the companion here spoken of, has died. A subsequent attack of fever in the Yaffi country (South Arabia) was accentuated by a chill caught on the homeward journey, and proved fatal. I little thought when I left my kind and courteous fellow-traveller at Aden on our return from Sokotra that the ‘good-bye’ was a final one.” (p. 408).

Socotra is of universal importance with a biodiversity of rich and distinct flora and fauna, much of which does not occur anywhere else in the world. It also has globally significant populations of land and sea birds, including a number of threatened species and an extremely diverse marine life

In order to raise awareness of the rich and distinct heritage of Socotra, UNESCO is collaborating with the Friends of Socotra in organising a campaign of awareness events and publicity around the world. Using the hashtag #connect2socotra, the purpose of the Connect 2 Socotra Campaign is to connect the world to Socotra, and connect Socotra to the world. Search Google for campaign news and events.