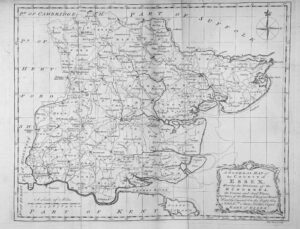

The aim of this short series of posts on the Essex homes (essentially northern Greater London, England) of Mabel’s kin – on her father’s side – is to give a quick look at the open spaces and sorts of landscapes that Mabel Bent (nee Hall-Dare) would have enjoyed as a young woman on the eastern shores of the Irish Sea, predisposing her to an adventurous, outdoor life – horses everywhere, rivers, forests, walks, new rail links, not to mention the travelling involved in getting up to Dublin from Co. Wexford and then across the sea to London (there were rented properties in ‘Town’ too of course), for stays in Essex before, for example, spending the long summers touring Europe with her siblings. Indeed, she was to meet her husband-to-be, Theodore Bent, in Norway on one such tour (although we still don’t know when, where, how, and why).

The Essex properties, lands, and churches featured will include: (1) ‘Fitzwalters’, (2) ‘East Hall‘, (3) ‘Ilford Lodge‘, (4) ‘Cranbrook‘, (5) ‘Wyfields‘, ‘Theydon Bois’, and others, all with links in one way or another with Mabel Bent.

No. 1: Fitzwalters, near Mountnessing, Essex, UK.

Of all the County Essex (England) properties owned or leased by Mabel Bent’s paternal connections, the Hall-Dares, Fitzwalters (west of Mountnessing, 51.650724, 0.336264) was perhaps the most outstanding, and certainly the most distinctive. The house and estate seem to have come into the possession of the Halls before 1820, on the death of Robert Hall’s friend Thomas Wright, a City banker, and was a favourite residence of Mabel’s father, Robert Westley Hall-Dare (1817-1866), who went on giving Fitzwalters as his address, even though the delightful mansion itself was destroyed by fire on the night of 24th March 1839 and never rebuilt. It seems the lands, with its several farms, were disposed of before 1860, when RHD was focusing on the rebuilding of his grand Irish home, Newtownbarry, Co. Wexford.

Of all the County Essex (England) properties owned or leased by Mabel Bent’s paternal connections, the Hall-Dares, Fitzwalters (west of Mountnessing, 51.650724, 0.336264) was perhaps the most outstanding, and certainly the most distinctive. The house and estate seem to have come into the possession of the Halls before 1820, on the death of Robert Hall’s friend Thomas Wright, a City banker, and was a favourite residence of Mabel’s father, Robert Westley Hall-Dare (1817-1866), who went on giving Fitzwalters as his address, even though the delightful mansion itself was destroyed by fire on the night of 24th March 1839 and never rebuilt. It seems the lands, with its several farms, were disposed of before 1860, when RHD was focusing on the rebuilding of his grand Irish home, Newtownbarry, Co. Wexford.

A piece in The Gardeners Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic Improvement (Vol. 15, May 1839, Art. V. ‘Queries and Answers’, p. 303) provides an excellent introduction to this lost architectural masterpiece: “Fitzwalters, known also by the name of the Round House, was opposite the nine-mile stone of the London road, in the parish of Shinfield [Shenfield, Essex]. In 1301 the estate was the property of Robert Earl of Fitzwalter. The mansion, now destroyed, was built by Mr. John Morecroft, in the 17th century, after an Italian Model, and was an object of general observation and curiosity, being of an octagon form. Notwithstanding this singular shape each floor contained four square rooms; the centre of the house was occupied by the chimnies [sic]; and staircases filled up two of the intervening spaces between the square rooms, while the remainder formed small triangular apartments, devoted to dressing-rooms, closets, &c. The interior was built chiefly of timber, the girders being of very large dimensions. Fitzwalters was many years the property and country residence of Mr. T. Wright [died 1818], the banker, of Henrietta Street, of whose representatives the late Mr. Hall, grandfather of the present possessor [Robert Westley Hall-Dare, Mabel Bent’s father] purchased the property. (Chelmsford Chronicle, as quoted in the Times, March 30th, 1839)”

surveyed: 1871 to 1873, published: 1881.

J.H. Brady’s ‘pocket guide’ of 1838 provides details from before the catastrophic fire: “FITZWALTERS, an ancient manorial estate in Essex, in the parish of Shenfield, one mile from the church of that place, north-west from the road between Ingatestone and Brentwood. This is supposed to have been, in 1301, the property of Lord Robert Fitzwalter (whence the name of the manor), and it was held, in 1363, by Joan, his widow, of the king in capite, by the service of supplying a pair of gilt spurs at the coronation. About 1400, it became the possession of the Knyvett family, and subsequently of John Morecroft, Esq., who erected the house, after what is stated to be an Italian model. The building is on low ground, and being of an octangular form, with the chimneys rising in the centre, has a very singular appearance. It has a piece of water in front, with a neat fancy bridge, and toward the road are two porter’s lodges. After Mr. Morecroft’s death, the manor was enjoyed successively by several families. It is now the residence of J. Tasker, Esq., but the property, we believe, of Robt. W. Hall Dare, Esq.” (J.H. Brady, A new pocket guide to London and its environs, London, 1838, pp. 262-263)

See also, Thomas Wright, The history and topography of the county of Essex, comprising its ancient and modern history, Vol II, London, 1836, p. 541.

For another old print of Fitzwalters, click here.

[Coming shortly (Nov. 2022) – No. 2: East Hall, Wennington]

The back story

Of course Mabel was fortunate in that her family (on both sides) were landed (obviously) and comfortably off. Mabel’s paternal grandfather was the first of the Robert Westley Hall-Dares proper, an astute, baronial, figure who sat at the head of a coalition of wealthy and influential Essex families (Halls, Dares, Graftons, Mildmays, Kings, to name but a few), garnering in with him two major estates (Theydon Bois and Wennington) and various other demesnes, farms, and assorted dwellings, large and small. His wealth and assets were based on rents, farming, ventures, deals, and investments – including a sugar plantation in what is today British Guyana. This plantation, ‘Maria’s Pleasure‘, still retains its name, although it was disposed of after Mabel’s father, to whom the sugar estate had been left, received his compensation for the emancipation of around 300 slaves after Abolition (worth the equivalent of several millions of pounds now).

Robert Westley Hall-Dare the first (1789-1836), the Member of Parliament for South Essex from 1832 until his death, rubbed shoulders with the great and the good, not to mention London Society, but it was his son Robert Westley Hall-Dare the second (1817-1866) who actually married into (minor) aristocracy with his marriage to Frances, daughter of Gustavus Lambart of Beauparc, Co. Meath – Mabel (b. 1847) was one of their daughters.

Mabel was thus free to travel; her husband was the perfect fit; they were never slowed down by children. But if anyone should say to you, ‘Ah, but Mabel never worked’, then they don’t know what they are talking about: few women of her class would have sweated more, from Aksum to Great Zimbabwe.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article