India, and all that the name evokes…

“And now I think we are among the most remarkable people in this world. Fancy going all the way to Bombay and departing thence without ever landing!” (from Mabel Bent’s Chronicle of 1889)

We begin our essay on Theodore and Mabel Bent and India not at the Taj Mahal, nor the Ellora Caves, but in leafy Brookwood Cemetery (Surrey, UK), an hour from London, on May 24, 1904:

“And why, it may be asked, were so many Indian and English friends gathered… in such a place on a dismal day in a downpour of rain? The day was dismal, and rightly so, for the obsequies were being performed of Mr. Jamsetdjee Nusserwanjee Tata, the foremost citizen, taken all round, that India has produced during the long period of British rule over the most cultured and civilised people east of Suez…”

For it seems, indeed, that Mabel Bent, and perhaps Theodore too, although dead and buried himself these seven years, was a friend, or at least an acquaintance, of the extraordinary Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata (1839-1904), the pioneer Indian industrialist who founded the Tata Group, India’s largest conglomerate company (as at 2021).

And in the same periodical that reports the industrialist’s funeral – the Voice of India, Saturday, 18 June 1904 (p. 583) – we have an image of Mabel, bearing flowers, her long red hair tucked under a black hat:

“From Mr. N.J. Moola I have received the following list of inscriptions attached to the wonderfully beautiful and choice flowers that were an eloquent expression of the affection in which Mr. Tata was held…”

And included in this list we find: ‘With deep sympathy, from Mrs. Theodore Bent,’ and Mabel remained friends with the family, as a cutting from the Belfast Evening Telegraph of Monday, June 28, 1913, indicates: “Mrs. Theodore Bent’s recent evening party was as great a success as her other functions have always been, and was particularly noticeable for the number of distinguished foreign and Colonial guests present. The suite of beautiful rooms, which form a perfect museum of curios from all parts of the world, were looking their best, and were crowded with guests of many nationalities, many of the ladies wearing diamonds in the form of tiaras and other ornaments, some of the handsomest being displayed by a Parsee lady, Mrs. Ratan Tata, who had splendid sapphires set into diamond frames as a necklace, and also for securing her white saree.”

To be able to associate Mabel, the archetypal Victorian, with the legendary ‘Father of Indian Industry’ seems somehow an unusual but fanfaring introduction to the Bents and India, with all the dynamics and symbolism in play between the nations at the end of the 19th century. India meant something, and meant adventures in and around the region for the Bents.

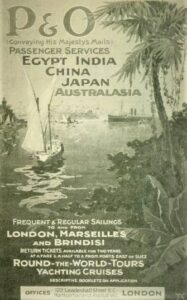

In all, our couple made three trips to India – not the London, ten-hour flight to Mumbai of today, but then, of course, traversing several seas (the Suez Canal was opened to navigation on 17 November, 1869). Let it be known, Theodore never expressed any sustained interest in exploring or excavating regionally in India, nor to travel and write about its culture; it seems the idea of the land was just too big for him to provide any focus or purchase, and there was something, too, in his psychology, that did not fit. And yet, such was the meaning of India, it would have been extraordinary indeed were he never to have set foot on the Asian continent. Thus, concisely, we can condense their trips to India into: one business meeting (1895), two transit stops (1889 and 1894), and one brief tourist excursion (1895).

But it was India nevertheless.

Theodore wrote no articles directly relating to these visits, the name ‘India’ appearing in just one title. For Mabel, her diary entries are strangely muted (as we shall read in a moment): there is no colour, no sensory Indian overload, as if British control of the ports they landed at and left from, without much exploration, had thrown an odd English and subfusc wash over everything.

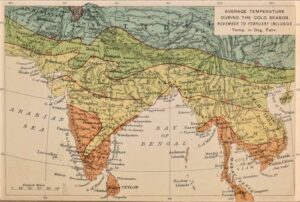

Their first Asian visit was in December 1889 – in a dramatic volte face and characteristic burst of energy and enthusiasm from Theodore that was to launch the couple out of their Eastern-Mediterranean orbit – having been denied further rights to ‘explore’ in either Greece or Turkey – and project them thousands of kilometres eastwards, for Bahrain, then under British and India Office protection, and with Theodore at relative liberty therefore to shovel-and-pick his way there through the ‘Mounds of Ali’. His fuel for this foray was an interest he had by the end of the 1890s in various long-standing theories and Classical references that seemed to link Bahrain with the Phoenicians, and in turn to the movement of early peoples around the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond – perhaps the theme that could be said to be the pivot of his short life’s work; his means of taking himself and his wife to Bahrain was via a slow boat from Karachi, then in India and under the British Raj. But their first port of call was to be Bombay.

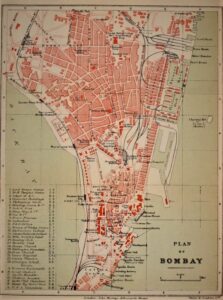

The summer of 1888 was taken up, as usual, with Theodore conducting a busy schedule of talks and lectures in England and Scotland, as well as a non-stop programme of article-writing and publishing. Late summer was the time for extended holidays in Ireland and northern England, seeing family and friends, and so it was not until after Christmas 1888 that Theodore and Mabel had everything in place to leave London. Through Suez, and changing at Aden, they reached Mumbai (then Bombay) after three weeks, and immediately left for Karachi and a cruise up the eastern side of the Persian Gulf; making a brief halt at Muscat, before crossing to Bushire, arriving there on 1 February 1889. From there they crossed the Gulf once more to reach Bahrain. (Their finds there, now in the British Museum, were modest and the couple spent only two weeks on the island.) By the end of February 1889 the couple are leaving again for Bushire, Mabel adding in her diary: ‘having passed 40 days and 40 nights of our precious time on the sea, we then and there made up our minds to return over land…’ And with this throwaway remark, Mabel announces the couple’s epic ride of some 2000 km through Persia, the first leg of their journey home to Marble Arch.

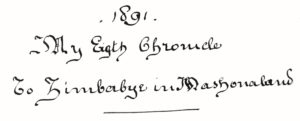

But let us now peer over Mabel’s shoulder and read her ‘Chronicle’ while she writes on the “British India S.S. Pemba, January 21st 1889, Monday. Passing Gujarat, India”

“I now for the first time [Monday, 21st January 1889] feel tempted to bring forth this book, as I am so soon to get off the beaten track. Theodore and I left London on December 28th (Friday) in the P.&O.S.S. Rosetta, not a very comfortable or clean ship and landed at Naples (Saturday) on the way and changed at Aden (Monday), with no time to land, to the P.&O. Assam, which, though smaller, is wider and has much better passenger accommodation and was very clean.

“We reached Bombay on Sunday 20th [January 1889] after a roughish time in the Indian Ocean, passing on Saturday the American racing yacht Coronet going round the world. There were few passengers on the ‘Assam’. And now I think we are among the most remarkable people in this world. Fancy going all the way to Bombay and departing thence without ever landing! We found the tender of the British India waiting hungrily for us and were carried off with the mails at once. This [i.e. the ‘Pemba’] is a very small ship and only one passenger for Kurrachi 1st class, but quantities of odd deck passengers dressed and the reverse. We have a cabin next to the little ladies’ cabin and their bath and all in communication, so Theodore has a dressing room and we are most comfortable. We are to call at several places on our way to Bushire. The sea is very calm and it is nice and cool and we are passing a coast like Holland with palms, or rather coconut trees.

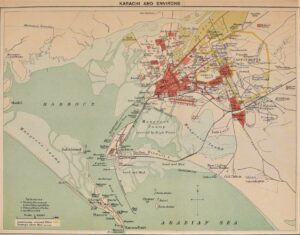

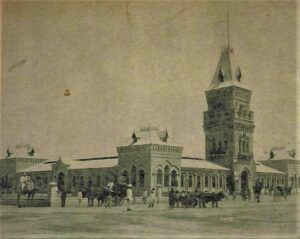

“We reached Kurrachi on Wednesday 23rd [January 1889] about 2 o’clock, and being tempted by the thought of 2 nights ashore, landed. We were surprised at the immense fleet of huge sailing boats which surrounded the ship instead of the usual little ones, but we were a good way out. They are building a new lighthouse further back and on lower ground but higher in itself, as the present one is being shaken by the guns on Manora Point.

“On landing on the bunder, or quay, we took a carriage for Reynold’s Hotel. After leaving the bunder, where various shipping buildings are, we drove for a mile or more along the bund, or embankment, across water and in about 6 miles we reached our destination. All around is arid and sandy but they are making a fierce fight to rear up some dusty plantains, palms, pepper trees, etc. The hotel was a great disappointment as the establishment is just a one-storeyed bungalow with a veranda all round and everyone’s door opening on to it and most with no kind of blind to prevent the inmates being beheld by outsiders. We found ourselves, when night came, in this case and so without ceremony flitted to a suite next door with imitation coloured glass. There was a dressing room behind and a built bath cemented in a bathroom beyond. All was very untidy and wretched and when night came we wished ourselves on board the ‘Pemba’.

“The cantonment road was near, also many others intersecting the sandy plain all 40 feet wide and one with footpaths fully 20. This led past the bungalows of officers, each in a compound, which made the road very long and dull, and it was very hot too. On Thursday [24th January 1889] we drove to the city about 4 miles off and nearer the sea and discovered the native town and wandered up and down narrow streets full of people intermixed with cows and passed several baths where people were washing themselves outside the buildings.

“We departed at dawn on Friday [25th January 1889] and drove down to the bunder and were off after breakfast, now the only 1st class. Friday night we stopped 3 miles out from Gwadar in Beloochistan, so of course saw nothing, and on Sunday morning, 27th [January 1889] early, found ourselves at Muscat in Arabia.”

Five years on – Karachi revisited: Bound for India a second time

For 1895, the Bents have decided to make a second attempt to penetrate regions of Yemeni Hadramaut, this time approaching from the south-east, via Muscat again and the coast of modern Oman. Their first trek into the Wadi Hadramaut, in 1894, was only partially successful, and on their return they soon made plans to try again. Mabel’s previous Chronicle had ended in an upbeat tone with ‘and if we possibly can we’ll go back’. In any event they only had a few months (and, as said before, they normally took a break in mid-summer to visit family and friends in England and Ireland) to seek backing and make all the necessary preparations, including informing the ‘media’. Ultimately Theodore was ready to issue a ‘press release’ to The Times (31 October 1894): “Mr. Theodore Bent informs Reuter’s Agency that he and Mrs. Bent are about to start another scientific expedition to Southern Arabia. Leaving Marseilles by Messageries steamer on November 12, they will proceed to Kurrachee, whence they will tranship to Muscat.”

For a first-hand account, we have an extract from Mabel’s classic book on their Arabian adventures – Southern Arabia (1900) – in which she explains (p. 228 ff):

“My husband again, to our great satisfaction, had Imam Sharif, Khan Bahadur [expedition cartographer of note on their last trip], placed at his disposal; and, as the longest way round was the quickest and best, we determined to make our final preparations in India, and meet him and his men at Karachi.”

But let’s at this point switch back to Mabel’s diaries, and her entry for: “Saturday 15th December, 1894. The Residency, Muscat. As it is now nearly a fortnight since I have seen a white woman, I think it time to start my writing. We left England [Friday] Nov. 9th [1894] and after 2 nights at Boulogne embarked at Marseilles on [Monday] the 12th [November 1894] on board the M.M.S.S. ‘Ava’. We had a good passage and warm, seeing Etna smoking on the way, and about 2 days after had a great white squall; I daresay in connection with the earthquakes. We transshipped at Aden to ‘La Seyne’, Theodore going ashore to see about the camp furniture left there 7 months ago.

“We reached Kurrachee on the morning of [Thursday] the 29th [November 1894] and a letter came on board from Mr. James, the Commissioner, asking us to stay at Government House, saying he was going to the Durbar at Lahore, but his sister, Mrs. Pottinger, would entertain us – and so she did, most kindly. She is so pretty and charming, I do not know which of us was most in love with her…

“We remained at Kurrachee till Monday night after dinner. We drove out every evening and one morning went to the bazaars. I bought a lot of toe rings of various shapes, silver with blue and green enamel. They were weighed against rupees and 2 annas added to each rupee. One day we went to call on 2 brides and bridegrooms, Mr. and Mrs. McIver Campbell and Mr. and Mrs. Thornton. The ladies, Miss Grimes and Miss Moody, had come out to our steamer, been married that day, and were passing their honeymoon together at Reynold’s Hotel, amid the pity of all beholders. We embarked [Monday 3rd/Tuesday 4th December 1894] on the B.I.S.N.S.S. Chanda with a little plum pudding Mrs. Pottinger had had made and mixed and stirred by herself and us, and Mr. Ireland, a young invalid officer who was being taken care of at Government House, and her young nephew, Mr. A. James. We were 3 days on the Chanda, a clean little ship with a very clever nice Captain Whitehead, and on Thursday morning [6th December 1894] we reached Muscat…”

A third and final return to India

Alas, this expedition along the Oman coast also turns out to be less than successful – although the couple made some remarkable discoveries. The fastness that was the ‘Wadi Hadhramout’ again resisted the Bents’ advances and the party found itself stranded at Sheher, on Yemen’s south coast, in late January 1895, in vain hoping to strike northwards into the Wadi area, or, failing that, to return to Muscat to explore further there.

Mabel’s expedition Chronicle of around this date is haphazard and, understandably, rather depressed. Something happens, and, as in nowhere else in her twenty years of diary-keeping, the detailed notes of the couple’s travels disappear. We get a few lines from the Yemeni south coast before moving with her on board the Imperator for Mumbai:

“[About Wednesday, 30th January 1895, Sheher] … The next 2 days there were great negotiations and plannings as to our future course. One plan was to go hence to Inat in the Wadi Hadhramout, down to Kabre Hud and Bir Borhut and thence to the Mosila Wadi; eastward and back by the coast to this place and then try to go westward. But the other is to us preferable; to go along the coast, first up Mosila and into the Hadhramout and then try to go west, without coming here again. Of course there are so many delays of all sorts that we shall be here some days yet. The one pleasure we can enjoy is a quiet walk along the shore covered with pretty shells and birds…

“A good long time has elapsed since I wrote and I resume my Chronicle. Sunday, February 17th [1895]. And hardly can I write for the shaking of the very empty Austrian Lloyd S.S. ‘Imperator’ bound for Bombay. After a good deal of illusory delay, the Sultan Hussein declared he could not answer in any way for our safety if we went anywhere and so we at first thought of going to Muscat in a dhow and going to the Jebel Akhdar, as we had intended if it had not been for Imam Sheriff’s illness, but with the wind blowing N.E. it would have taken fully a month. We then must have gone round by India to get home and all our steamer clothes were at Aden. So as soon as we could we hired a dhow and embarked thereupon at about 1 o’clock for Aden…”

Back on dry land, we know the Bents were in Aden again by Wednesday, 13 February 1895. On that date Theodore wrote a ‘press release’ via the Royal Geographical Society, which was published in The Times of 1 March, announcing that ‘The party… went on to Sheher… Last year the people were very friendly to Mr. Bent’s party and promised to take them on a tour into the interior, but the season was too far advanced. To Mr. Bent’s surprise, however they received him and his party very coldly, absolutely refused to let them go outside the town, and told them that for the future no European would be allowed to enter the Hadramaut… Although it is evident Mr. Bent has not been able to carry out what would have been an expedition of the first magnitude, still it would seem that his journey will not be without interesting and novel results. His latest letter is dated from Aden, February 13, and he expects to be home about the middle of April.’

And they will come home via India; and Mabel’s few lines above are all we have of the Bents’ last trip there. Why did Mabel not keep up her diary? They would have reached Bombay on the Imperator (a lovely ship of 4140 tons, launched in September 1886 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Lloyd Shipping Company) by the end of February 1895, and we know the two of them were back in London by the end of April.

The Manchester Guardian of 25 April 1895 carried another report: ‘Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent have returned to London after spending the winter in exploring some of the little known or entirely unknown valleys of Southeastern Arabia. The flying trip which Mr. Bent made to India to see Colonel Holdich, the head of the Indian Survey, as to some unexpected difficulties, presumably of official origin, thrown in the way of the realisation of his plans for visiting the Eastern Hadramaut Valley, was unfortunately unsuccessful, as Colonel Holdich was absent on frontier business…’

Allowing for a two- or three-week journey back to England, Theodore and Mabel would have remained three or four weeks in India. As we have read above, one mission Theodore had in the country was to try and find his friend the great ‘Superintendent of Frontier Surveys in British India’, Colonel Sir Thomas H. Holdich, intending to elicit his support for one further expedition to the Hadramaut.

But Mabel’s above note, about needing Aden again to collect their personal effects, including ‘steamer clothes’ prior to making for Bombay, leads indirectly to one last bit of classic tourism and sightseeing – the fabled Ellora Caves. It looks, however, as if Mabel never went along; indeed, the only reference we have to the trip comes after Mabel’s death in 1929; prompted by her obituary in the Times, a letter appears in the same newspaper a few days later. This letter, of 6 July 1929, is from Mrs Julia Marie Tate, of 76 Queensborough Terrace, Hyde Park, London, widow of William Jacob Tate, in which she wistfully recalls:

“… a vivid picture of a moonlit night as clear as day off Aden, watching Arabian ‘sampans’ unloading tents and quantities of camp ‘saman’ [personal effects]. Presently their owners climbed up, Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent. A few months before [i.e. the winter of 1894/5] we had called at their [London] house in Great Cumberland-place to learn their whereabouts, but the *butler knew nothing, only that they were ‘somewhere in the Indian Ocean.’ This improvised meeting brought about the fulfilment of a cherished desire of theirs when my husband took his old schoolfellow to see the wonder caves of Ellora. This was their last reunion on earth.”

It is remarkably odd that Mabel makes no mention of this trip to the ‘wonder caves’ – was she ill? Or prevented somehow from going? Did it cause such resentment that she refused to chronicle the stay in Mumbai, and the long journey home by sea? Her regret at missing out on this excursion – then as now one of India’s greatest tourist attractions – can be imagined, for she was not easily denied. Also unusual is the fact that Theodore also wrote nothing about the visit to the caves (a trip that would have necessitated several nights away from his wife) – he did have much else on his mind, but perhaps also he had no desire to bring up the matter again and avoid any breakfast-table ill will!

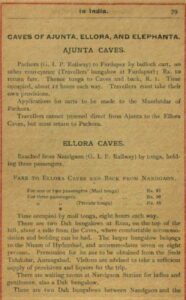

And his companion? William Jacob Tate (1853-1899) was at Repton School with Theodore in the late 1860s. He joined the Indian Civil Service but had to retire early on account of his health and died just two years after Theodore in December 1899, at the age of 46. Mabel and Mrs Tate perhaps remained in town while Theodore and his old school friend visited the Ellora cave complex of monasteries and temples carved in the basalt cliffs north of Aurangabad (Maharashtra State), some 300 km north-east of Mumbai – “Reached from Nandgaon (G.I.P. Railway) by tonga, holding three passengers… Visitors are advised to take a sufficient supply of provisions and liquors for the trip.’ (Thomas Cook: India Burma and Ceylon : information for travellers and residents (1898, p. 79)

As for Mrs Tate, she can be forgiven her unseen tears in her letter to the Times. A stone in the Kemmel Chateau Military Cemetery Heuvelland, Belgium, is inscribed: ‘Tate, Lieutenant, William Louis, 3rd Bn., Royal Fusiliers. Killed in action 13 March 1915. Age 24. Eldest son of the late William Jacob Tate, I.C.S., and of Mrs. Julia Marie Tate.’ And the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial has this: ‘Tate, Captain, Frederick Herman, Mentioned in Despatches, 10th Bn., King’s Royal Rifle Corps. 11 August 1917. Age 22. Son of Mrs. Tate… the late W.J. Tate.’

The old steamer on her westward bearing leaves Bombay in her wake. No amount of meditation in the Ellora Caves, or anywhere else, will ease such wounds, be it for Tate or Tata: ‘With deep sympathy, from Mrs. Theodore Bent.’

References to Mabel Bent’s diary from: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Vol. 3, Arabia (2010) and the Bents’ travel classic Southern Arabia (1900)

- * The ‘butler’ here is Mr. A. Lovett, and it is a pleasure to reference him; how nice it would be to trace his descendants (if any). Sadly, he was to lose his job on Bent’s demise in May 1897. The Morning Post of 13 May prints this notice: “Mrs. Theodore Bent can recommend A. Lovett as Butler: four years’ character; leaving through death. – A.L., 13 Great Cumberland-place, W.”

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article