(We are delighted to post here a translation (by the author) of an article on some traditional musical instruments enjoyed so much by celebrity explorers Theodore and Mabel Bent when they visited the Cycladic island of Tinos in March 1884. Dr Chiou’s article originally appeared (March 2024) in the newsletter of the Society for Tinian Studies.)

By Dr Theodoros Chiou note 1

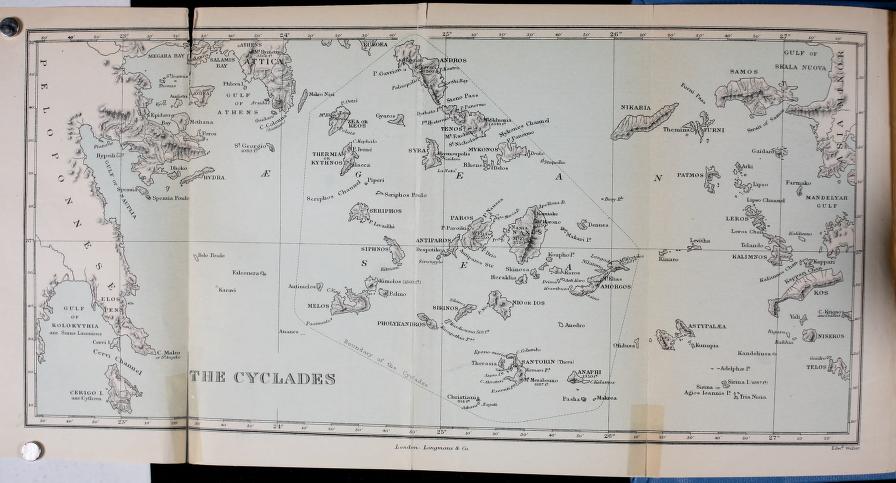

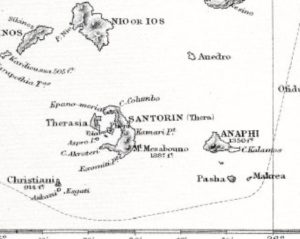

Theodore Bent and his wife Mabel Virginia Anna Bent were 19th-century British explorers who travelled the Cyclades. On a sunny Saturday afternoon in March 1884, they found themselves in the port of the island of Tinos (or Tenos), coming from Mykonos. It was the Saturday before Carnival Sunday. On the evening of the same day, koukouyiéroi (masqueraders) roamed around the narrow streets of Agios Nikolaos, as the present-day Chóra was called at that time. For the next three days, the Bents mounted mules and toured the Tinian hinterland. On Carnival Sunday they visited Xómbourgo and Loutrá and returned to Chóra. On ‘Kathará Deftéra’ (the first Monday in Lent, literally ‘Clean Monday’), 1884, they climbed up to Kechrovoúni, visiting the Monastery of Kechrovoúni, Arnádos village, and ending up in the village of Dío Choriá. On Tuesday they reached the village of Pýrgos, after making a stop at the villages of Kardianí and Ystérnia, in the north-western part of the island. Mabel writes in her diary that on Wednesday, 5th March, they returned to the bay of Ystérnia, where they boarded the steamer that would take them to the nearby island of Andros.

The above information comes from what Bent himself recorded in his classic travelogue The Cyclades, or Life among Insular Greeks, published in 1885, and which is still in print today, and from the account in Mabel’s ‘Chronicles’. Thanks to Bent’s observant and meticulous descriptions, we have the following account of how the inhabitants of the village of Dío Choriá spent their ‘Kathará Deftéra’ at the end of 19th century:

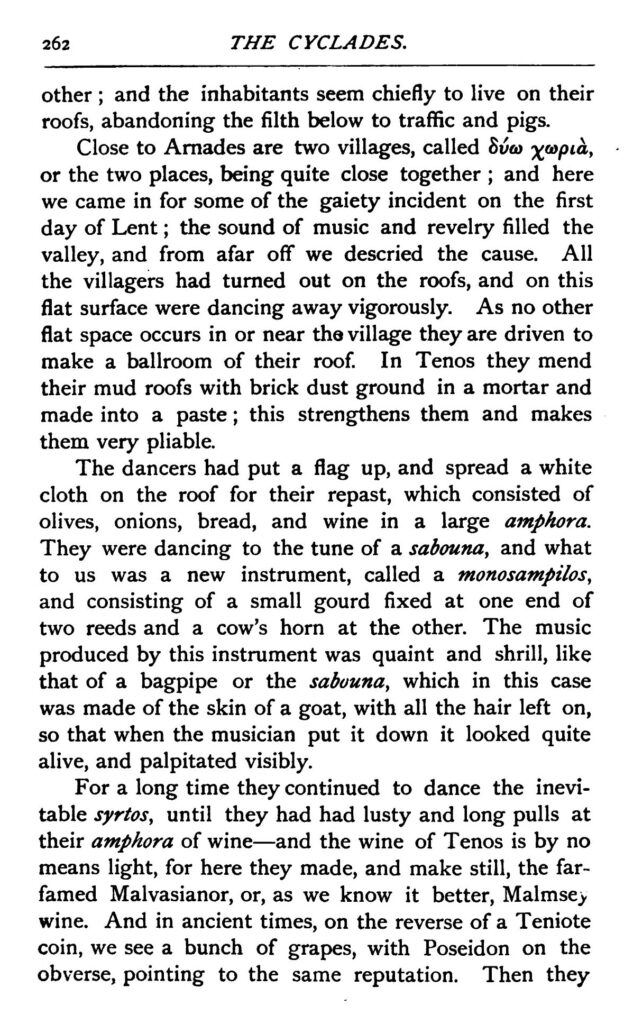

Close to Arnades are two villages, called δύοχωριά, or the two places, being quite close together; and here we came in for some of the gaiety incident on the first day of Lent; the sound of music and revelry filled the valley, and from afar off we descried the cause. All the villagers had turned out on the roofs, and on this flat surface were dancing away vigorously. As no other flat space occurs in or near the village they are driven to make a ballroom on their roof. […]

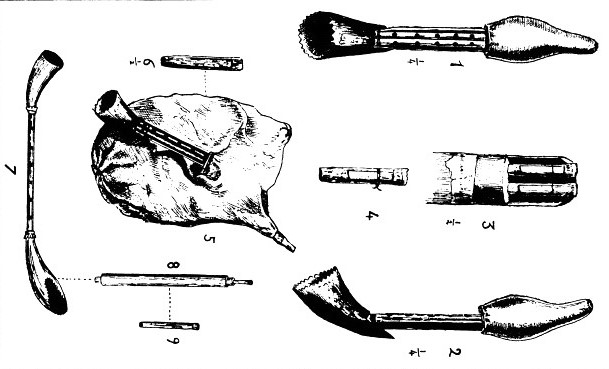

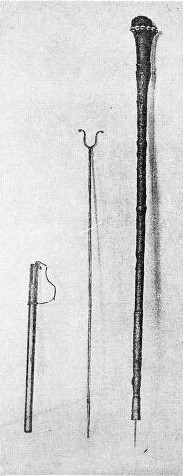

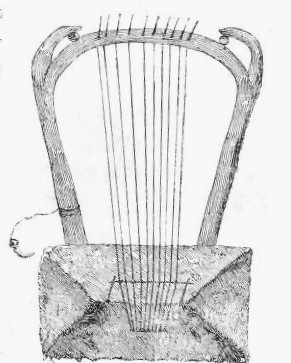

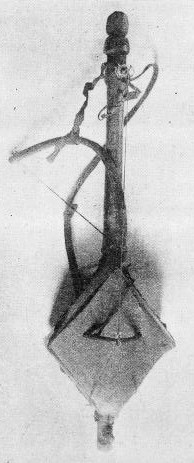

The dancers had put a flag up, and spread a white cloth on the roof for their repast, which consisted of olives, onions, bread, and wine in a large amphora. They were dancing to the tune of a sabouna, and what to us was a new instrument, called a monosampilos, and consisting of a small gourd fixed at one end of two reeds and a cow’s horn at the other. The music produced by this instrument was quaint and shrill, like that of a bagpipe or the sabouna, which in this case was made of the skin of a goat, with all the hair left on, so that when the musician put it down it looked quite alive, and palpitated visibly.

For a long time they continued to dance the inevitable syrtos, until they had had lusty and long pulls at their amphora of wine – and the wine of Tenos is by no means light, for here they made, and make still, the far-famed Malvasianor, or, as we know it better, Malmsey wine. […] Then they started a dance called by them ‘the carnival dance’ (ἀποκρεωτικός), which they said they were privileged to dance on the first day of Lent. It was a very amusing one: eight men took part in it with arms crossed, and moved slowly in a semicircle, with a sort of bounding step, resembling a mazurka. Occasionally the leader took a long stride, by way of adding point to the dance, but they never indulged in the acrobatic features of the syrtos, and never went so very fast; the singing as they danced was the chief feature and fascination of this carnival dance, and their voices, as they moved round and round, to the shrill accompanying music, had a remarkable effect. The words of their song, which I took down afterwards, formed a sort of rhyming alphabetical love song. It is needless to say that A stood for love (ἀγάπη). Θ spoke of the death (θάνατος) which would be courted if that M or apple (μῆλος) of Paradise was obdurate. P stood for ῥόδον, the rose, like which she smelt. Ψ was the lucky flea (ψύλλος) which could crawl over her adorable frame, and so on, till Ω closed the song and the dance with great emphasis, imploring for a favourable answer to the suit.

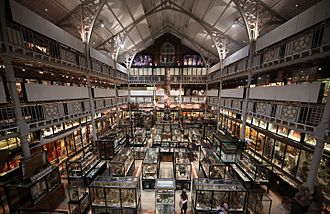

This vivid description is a valuable document in terms of the history of the bagpipe (tsaboúna) on Tinos. It confirms the use of the tsaboúna (pronounced there as ‘saboúna’) as an instrument played at feasts during the Carnival period, and with which they performed not only tunes to the rhythm of the syrtós, but also to the tune of the ‘ἀποκρεωτικός’ (apokreotikós) dance. The latter can be associated with the ‘apokrianós’ dance, also performed, until the middle of the 20th century, in the nearby village of Triantáros. Bent also gives us information about the morphology of the tsaboúna (a goatskin bag with the hair on the outside), and conveys an important account of a rare folk hornpipe, which the 19th-century revellers from Dío Choriá, who sold it to Bent, called ‘monotsábouno’ (while villagers from Ystérnia called it ‘kelkéza’). We are fortunate that this very same instrument survives intact to the present day in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

However, if one has to choose the most important contribution of Bent’s testimony above, then it must be that it offers us the earliest starting point – a terminus ante quem – for research into the tsaboúna on Tinos. Of course, it can be reasonably assumed that the tradition of the tsaboúna on the island is much older, being a manifestation of the wider, older spread of the bagpipe (áskavlos) in the Aegean Sea area. However, thanks to Bent, the tsaboúna is now undoubtedly and tangibly recorded as part of the Tinian musical tradition.

The thread of this tradition connects the unknown tsaboúna player (tsabouniéris) of Dío Choriá of 1884 with the tsaboúna players of the 1970s, who played the ‘saboúnia persistently in Carnival season’ in the village of Arnados, and also reaches back to the last tsabouniéris of the 20th-century generation of musicians, for example Yiórgos Tzanoulínos, or ‘Krínos’, from Falatádos. The thread of this tradition goes ahead with the reappearance of the tsaboúna on Tinos in the second decade of the 21st century, in the context of, among others, events such as the Tinos World Music Festival 2021; The 18th Aegean Folk Wind Instruments Meeting (28-30 September 2022, Kea Island); and during New Year’s carols on Tinos at Chóra and Falatádos (2022 and 2023).

So, what more enjoyable occasion than to continue the revival of the Tinian tsaboúna, from the place where Bent first records for us, at a ‘Kathará Deftéra’ celebration in March 1884, with a tsaboúna party and ‘apokrianós’ dance in the square of Dío Choriá, more than a century and a half later!

Return from Note 1

Sources

7th Tinos World Music Festival, Tinos, 2-4 July 2021, Sunday, 4 July 2021, Part B: Tsambouna – The Askavlos of the Cyclades (https://itip.gr/events/twmf2021/).

Apergis, Savas 2007. The ‘Apokrianos’ of Triantaros, newspaper ed. by the Association of Triandarites Mandata, vol. 28, Dec-Feb 2007: 6-7.

Baines, Anthony 1960. Bagpipes: 45. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Bent, J. Theodore 2009 [1885]. The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks: 123-131. Annotated revised edition, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Bent, Mabel V.A. 2006. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Volume I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral: 47. Archaeopress, Oxford.

Brisch, G.E. 2024. The Bents’ musical instruments in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford (article dated 5 Feb. 2024).

Danousis, Konstantinos (ed.) 2005. Tradition and Memory. With the bow and the pen of Kostas Panorios, publication of the Society for Tinian Studies and the Brotherhood of Tinian Cardianiotes, The Holy Trinity: 30-31.

Moschona, Styliani 1975. Collection of folklore material from the village of Arnados, on the island of Tinos, in the prefecture of Cyclades. Archive of primary folklore material – Collection of manuscripts (NKUA), no. 2413.

Two other Bent Archive articles that might interest you:

Theodore and the Tsabouna (video)

VIDEO – Manolis Pelekis: A lament for the great tsabouna player from Anafi

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article