There is a backstory to Bent’s The Life of Giuseppe Garibaldi (1881). Theodore Bent had left Oxford with an undistinguished history degree in the mid 1870s, met and married a distant Irish cousin, Mabel Hall-Dare, in 1877, and then promptly took his new bride off to Italy, where he was to practise ‘history’, i.e. travel, write, and research, until 1882; the couple, wealthy enough, would use their London townhouse at 43 Great Cumberland Place as an occasional retreat the while.

The heady years of the couple’s status as celebrity explorers were a decade away; as yet, Bent had no career, but he did have a devoted wife, with whom he was lucky enough to share the traveller’s gene – that labelled ‘the need to be somewhere else’; thus he and Mabel were perfectly happy, and no thoughts of children ever appear in her diaries. Plus, as said, they were wealthy enough.

For Theodore, the fruits of these (non-fully unified) ‘Italian’ years ripened into a trilogy of books, two of which he managed to get the very solid London firm of Longmans, Green & Co. to publish. The first (1879, Kegan Paul & Co.) was a lightweight, but well received, account of the tiny Republic of San Marino, illustrated by its author – Theodore’s sketches pepper nearly all his books, with Mabel adding the photos on occasion. This modest work, besides getting the couple citizenship of the little state, obviously did well enough for Bent’s second publishers, Longmans, to agree to issue next (in 1881) an indigestible tome on the great port-city of Genoa, a study only really memorable as an example of Bent’s energy and speed of output – qualities he retained all his short life, producing hundreds (see his bibliography) of articles, papers, and lectures, in addition to his six books (a seventh was to be completed by Mabel after his death in 1897).

In the same year as Genoa (1881), Bent completed his biography on Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), the hero-revolutionary. We don’t yet know why exactly took on the project, although clearly the great man was nearing the end of his life and there was always interest in him, i.e. a market for one more leather-bound volume to add to library shelves. On a personal level, the boy Bent might have read of Garibaldi’s visit to the UK in 1864 – Theodore would have been 12; the young Oxford student would have studied the exploits of the man during his historical researches, no doubt; Chapter 11 of Bent’s guide to San Marino is taken up with the General’s entry to, and escape from, its capital in the summer of 1849.

Although Garibaldi, of course, was deeply associated with Genoa, he only appears by name on one page (412) in all the 420 of Bent’s book on how the Republic rose and fell. But, inescapably, the General must have been on the young Bent’s mind (he was born in 1852) ever since his ‘honeymoon’ in San Marino, if not before. As for the author’s material and sources – well, hardly anything is referenced and there are no detailed bibliographies in any of his three ‘Italian’ books, nor even indices. We may safely assume he would have consulted what biographical information he could find, including the autobiography of his warrior hero, edited by Alexandre Dumas père and translated into English two decades previously (1860, London: Routledge & Co.).

How did Bent get his data and was it accurate? He certainly did tour the locations (often with Mabel to take notes no doubt), perhaps making earlier visits as undergraduate; he talked to witnesses, and there would have been newspapers, articles, and published accounts, but ultimately Bent gives very little away in terms of sources (a serious oversight for an academic of course). Nevertheless, his Garibaldi appears in London at the end of 1881, just months after Genoa – no little achievement when one thinks of the proofing and printing processes of the time.

And immediately there are problems. The young historian finds himself under attack – the Garibaldi lion has been poked. Enter the family’s champion, the unquenchable Englishwoman Jessie White Mario (1832-1906). Needless to say, this present article isn’t nearly robust enough to accommodate her, and readers are directed elsewhere; suffice it to say that she had been devoted to, obsessed with, Garibaldi and his cause for decades – one of the hundreds of women drawn to the romantic warrior (think Che Guevara here). Evidently planning a biography herself, she was pipped to the post by Bent, and, swiftly acquiring a copy, went through it with a fine-tooth comb looking for issues, of which there was no shortage. From her villa in Lendinara (Rovigo, Veneto, northern Italy), blood up, she immediately wrote to Garibaldi’s son Ricciotti (1847-1924) – his father now infirm and passing his time on the family’s private island of Caprera, off, Sardinia – listing the inaccuracies, slanderous and actionable, as she saw them (Ricciotti, in Rome, had not yet seen a copy). She offered to enter the fray on the family’s defence and remonstrate directly with Longmans in London, insisting that they withdraw Bent’s book. Ricciotti’s reply to White Mario picks up on some of her points, accepts her offer, and asks to be sent a copy. From the list of offending passages, two examples illustrate Bent’s clear suggestions of corruption: one referencing a contract for granite from Caprera, the other a luxury yacht (some things don’t change). note 1

The accusations by Bent are unambiguous. Good as her word, White Mario, assisted by her brother, writes angrily to Longmans, who reply promptly (and anxiously), sensing a diplomatic misunderstanding of some scale, and possibly expense. On 31 January 1882, just a few months into sales of Bent’s book, a representative of his publishers replies to White Mario, saying that Mr Bent’s (for some reason they give his name as William) “only wish has been to give an unbiased view of Garibaldi’s life: that if he had been led by false information into making any statements that are not true he much regrets it…” Additionally, Bent would be pleased to make any corrections requested, and the letter ends: “[We] shall be glad to get the matter settled with as little delay as possible, as the suspension of the sale of the book so soon after publication involves us in inconvenience and pecuniary loss.” In a further letter dated 12 April 1882, Longman’s declare the first edition of Garibaldi, a Life as being formally ‘withdrawn’.

Our guide through this above maelstrom is Elizabeth Adams Daniels, via her swashbuckling study Jessie White Mario: Risorgimento Revolutionary, published by Ohio University Press in 1972. (The author refers, generously, to Theodore Bent as ‘one of Longman’s popular writers on Italian subjects’, mining the publishers’ archives and other sources for evidence of White Mario’s interventions on behalf of the Garibaldi family.) note 2

Notwithstanding this retreat before the General, a second edition of the biography does appear just a few months later, in 1882 (there was by now an eager market for it, its subject, sick and verging on bankruptcy, having been led away to fight in pastures new on 2 June of that year). Adams Daniels infers that this new iteration contained errata sheets, but these do not seem to have surfaced online. As we shall see later, when comparing extracts from the two versions, alterations were made to Bent’s text directly.

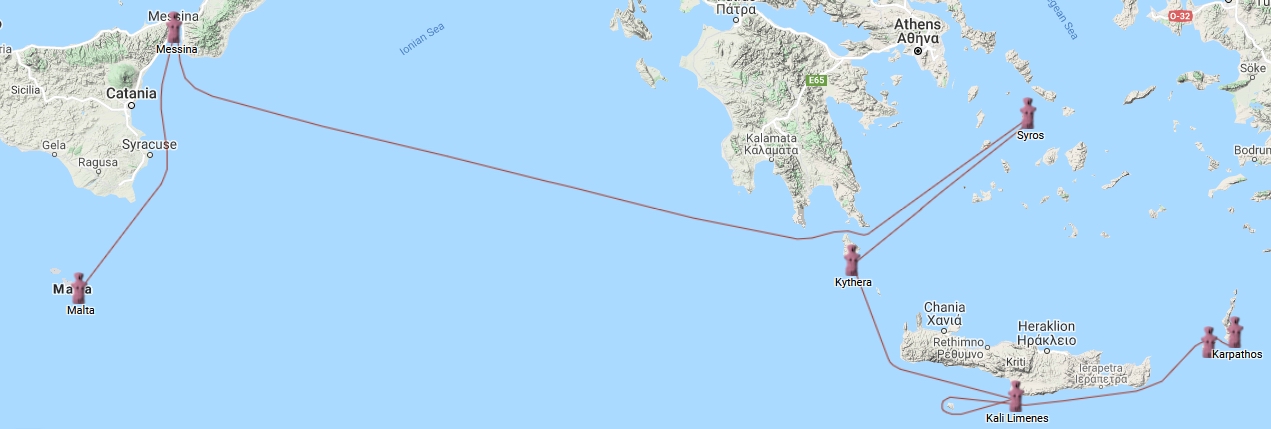

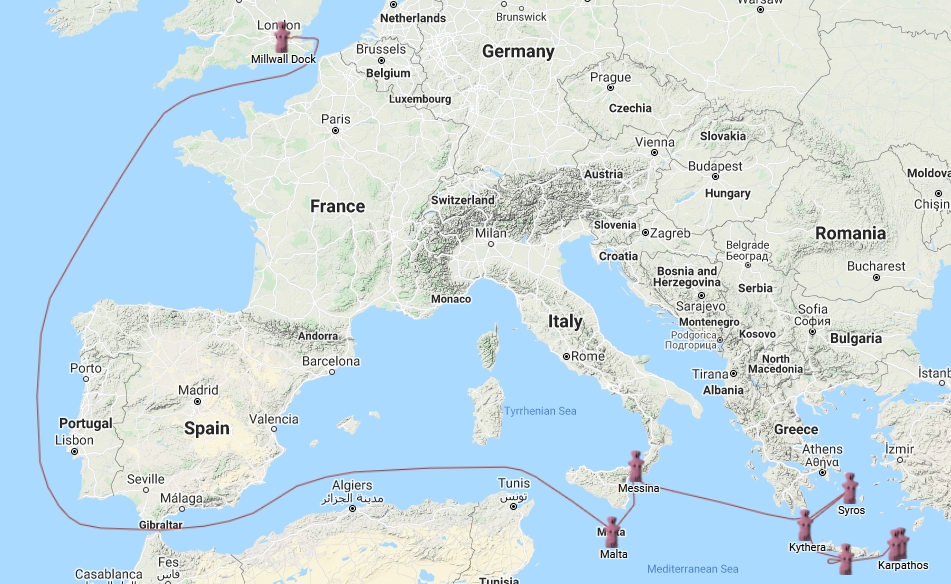

The life and times of Garibaldi drew a line under Bent’s attempts at ‘Italian’ historical memoires and there is to be no Italian ‘quartet’. (We need only look at lines from one of the reviews: “Mr. Bent should have abstained from sneering at the evening of a life which has certainly been useful to mankind.” – The Graphic, 19 November 1881, p. 519.) The couple’s next phase of travels was to take them into the Aegean and the Levantine littoral, possibly in the wake of the merchant vessels of the Genoese Empire, eastwards, over the winter of 1882/3. The end of 1883 sees the Bents blown into the Greek islands, and the traveller’s next book, on the Cyclades, was to establish his change of locale and literary style – essentially the exploits of explorer and travel writer, themes much more suited to his nature. After the Levant, the Bents tackled Africa, and then Arabia, in 20 extraordinary years of explorations.

Despite the obvious loss caused to Longmans over the Garibaldi issue, the firm was, it seems, prepared to remain Bent’s publisher for his next three books (Cyclades – 1885; Mashonaland – 1892; Aksum – 1893); their investment in the travel writer paid off, all three were bestsellers and ran to several editions. These can be acquired today either as originals, from antiquarian sources, or as new reprints, or via online versions.

Bent has been in print since 1877, and well merits it.

Textual comparisons

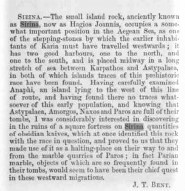

Page 96 of Bent’s Garibaldi (1st edn, 1881): “Caprera is rich in granite; the Pantheon at Rome was built of stone fetched from thence, and so was part of the Pisan Cathedral, and other celebrated buildings. In 1870, a contract was entered into for supplying Rome with some of it, for the improvements going on in the Eternal City. Ricciotti Garibaldi managed the affair, and put a little money into his pockets by the transaction.”

Page 96 of Bent’s Garibaldi (2nd edn, 1882): “Caprera is rich in granite ; the Pantheon at Rome was built of stone fetched from thence, and so was part of the Pisan Cathedral, and other celebrated buildings. In 1870, a contract was entered into for supplying Rome with some of it, for the improvements going on in the Eternal City, but the negotiations to a great measure fell through, and the Garibaldi family got but little money therefrom.”

Pages 234/5 of Bent’s Garibaldi (1st edn, 1881): “Garibaldi would not receive a purse from his English friends. They wished to subscribe a sum of money, which, if invested, would secure him from want for the rest of his days. As yet his sons and his son-in-law were not so deeply involved as to oblige him to take it; but he gladly accepted the yacht Osprey [Princess Olga], which they offered him, for the old General loved to skim along the blue waters of the inland sea, and there it lay for awhile at Caprera, until, as is the fate with most toys, the General got tired of it, and went out to sea in it less and less. Ricciotti Garibaldi looked on with covetous eyes at so much wealth lying idle in the harbour of Caprera, so he asked his father’s permission to go a cruise one day in the Osprey, which was readily granted, and since then the Osprey has not been seen in the waters of Caprera.”

Pages 234/5 of Bent’s Garibaldi (2st edn, 1882): Garibaldi would not receive a purse from his English friends. They wished to subscribe a sum of money, which, if invested, would secure him from want for the rest of his days; yet, notwithstanding, he gladly accepted the yacht Osprey [Princess Olga], which they offered him, for the old General loved to skim along the blue waters of the inland sea, and there it lay for awhile at Caprera, until, as is the fate with most toys, the General got tired of it, and went out to sea in it less and less; it was eventually sold to the Italian Government, and Prince Amadeo, Duca d’Aosta, went several trips of pleasure therein.”

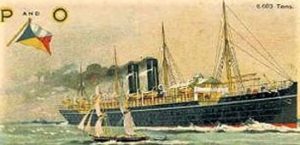

Garibaldi’s Yacht

Bent got this wrong. There was indeed some gossip (Liverpool Mercury, 2 August 1864) that Lord Burghley’s beautiful yawl the Osprey (built in Renfrew in 1854) would find her way to Garibaldi at Caprera, but the deal foundered, probably because she was too small at under 20 tons. The idea at all that a yacht should be purchased via a British subscription fund (‘The Garibaldi Yacht Fund’) took to the water in Liverpool in the early 1860s (the General knew the famous port powerhouse well). In the end it was not the Osprey but the schooner Princess Olga (built 1846) that was acquired and crewed out to him: “General Garibaldi has accepted the yacht Princess Olga, presented to him by various friends in England and Scotland. The Princess Olga sailed from Cowes on the 24th of October [1864], and arrived all safe at St. Roques, eight miles from Gibraltar, on the 8th inst. She sailed the next morning for Caprera” (The Illustrated London News, 19 November 1864, p. 519).

The sleek-rigged vessel was named after the famed beauty Olga Nikolaevna of Russia (1822-1892), who would still have been Princess Olga in 1846 when her eponymous yacht was launched off Cowes, Isle of Wight. As wife of Charles I of Württemberg from 1864, she took the title of Queen.

The story was wired all over the Empire, e.g.: “The Princess Olga, schooner, 50 tons, has been bought by the committee of the Garibaldi fund to be presented to General Garibaldi, for his use at Caprera. This vessel was built by Mr. Joseph White, of East Cowes for Mr. Rutherford, of the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, who himself furnished the design. She is built of the best India teak; copper bolted and fastened. Her internal fittings are commodious and elegant. Her saloon and ladies cabin were painted by Sang and his assistants, the fruit and flowers by Benson, the figures by Bendixen. Her head, a likeness of the Princess Olga, of Russia, was carved by [Hellyer], of Portsmouth. She is very fast, and has won many prizes, and has been long recognised as the show yacht of her class.” [Reprinted in the Launceston Examiner [Tasmania], Thursday, 15 December 1864]

And her fate? This must await another researcher: “The fact is that by 1874… people were becoming increasingly aware of the Garibaldi’s misfortunes and precarious financial condition. In 1869 he sold the yacht donated by British admirers, the Princess Olga, to the state for 80,000 lira, but the proceeds were stolen by the intermediary.” (Alfonso Scirocco: Garibaldi. Princeton University Press, 2007, p. 395)

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article