Alan King, long-term traveller in Greece, is in the front row as the Bents take to the stage in the Cyclades…

Overview

Between December 1883 and March 1884, Theodore and Mabel Bent were travelling around the Cyclades in search of ancient sites that they could excavate.

In December 1883, they stayed for a single night on the island of Antiparos, as Mabel recounts, “carrying only our night things and a card of introduction from Mr. Binney for Mr. R. Swan who has a calamine mine on this island.”

In the short time they were there, on the basis of information provided by Robert Swan, they visited an ancient burial site and found, and opened, four graves. This initial dig prompted their return a few weeks later for a longer visit in the hope that it would yield further finds.

Bent was the first player on stage and he wrote about his excavation work in 1884 note 2 but omitted to disclose the precise location of his two excavation sites.

Following Bent, some fourteen years later, in 1898, the Greek archaeologist Christos Tsountas took the stage when he located a site which he attributed to Bent’s initial site at a place he named as Krassades, but knowledge of exactly where Krassades lay was lost over the ensuing years.

For well over a century, the location of Bent’s site remained a mystery and the theatre stood silent. Only recently, thanks to the efforts of Dr. Zozi Papadopoulou, has the location of Krassades been pinpointed and the footlights have once again illuminated the scenery and the actors involved.

But the answer had always been there, hidden between the lines of Bent’s book and Mabel’s chronicles, ready to be revealed in conjunction with a little local research.

In 2017, Dr. Zozi published a paper note 3 , in Greek, in which she describes rediscovering the location of Krassades. Unfortunately, Dr. Zozi’s paper slipped under the radar of The Bent Archive.

On a visit to Antiparos in September 2019, unaware of Dr. Zozi’s discovery, I resolved to try to put together the pieces of the 130-year old jigsaw puzzle which would reveal: 1) the house of Robert and John Swan, in which Theodore and Mabel Bent stayed while on the island; 2) the site of the calamine mine managed by Robert Swan; and 3) the precise location of Bent’s initial dig. Together they form the three scenes for the set of the “Archaeology Theatre of Antiparos”.

The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks – Theodore’s classic book of his and Mabel’s adventures in Antiparos and the other Cyclades islands can be found in this print version, which also contains additional information about the Bents and their travel itinerary.

The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks – Theodore’s classic book of his and Mabel’s adventures in Antiparos and the other Cyclades islands can be found in this print version, which also contains additional information about the Bents and their travel itinerary.

The cast (in order of appearance)

Theodore and Mabel Bent

Theodore and Mabel Bent are the main players in the story. Read more about their lives and their travels.

William Binney

William Binney seems to play a small but important part in the story. He was Her Brittanic Majesty’s Consul to Syra (Syros) during much of the time of the Bents’ travels around the islands. He facilitated their travels by way of letters of introduction to important figures on each island they visited, one of whom was Robert Swan on Antiparos. Many of the Bents’ finds were illegally exported out of Greece, usually via the port of Syros, and one wonders whether William Binney’s role should be extended to include his services to the Bents in this area. Read more about William Binney.

Robert Swan

Robert McNair Wilson Swan was born in Scotland in 1858, making him 3 years younger than Bent. His biography tells us that he worked in Greece as a ‘mining expert’ from 1879 to 1886. He would have been around 25 years old when he and his brother, John, first met Theodore and Mabel Bent in Antiparos in December 1883. We deduce that he’d been working on the island for around four years at that stage. (For his obituary scroll to end of here).

Christos Tsountas

Christos Tsountas was a highly-respected Greek archaeologist. He was born in 1857 and died in 1934. Aside from his other important areas of work, notably Tiryns, Mycenae and Syros, he investigated ancient burial sites on several islands in the Cyclades in 1898 and 1899, including Antiparos. It was he who coined the term “Cycladic civilization”.

Dr. Zozi Papadopoulou

Dr. Zozi Papadopoulou is Head of the Department of Classical and Prehistoric Antiquities of the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades. Among other projects, she has been the driving force in rediscovering, and continuing work at, the site of Bent’s first excavation, now known as Krassades.

Setting the scene

In December 1883, Theodore and Mabel Bent visited the island of Paros, and, during their visit, they made the 10-minute hop across the narrow strait to the neighbouring island of Antiparos, armed with a letter of introduction from the British Consul in Syros, Richard Binney, to a Scottish engineer, Robert Swan, carrying out mining operations on Antiparos. They stayed for just one night with Swan and his brother John, but this brief encounter sowed the seeds of a friendship which would last for many years. Over the following few weeks, they saw more of Swan, who joined them on parts of their island-hopping odyssey.

This budding friendship was in stark contrast to that which Bent had feared he would encounter in Antiparos after advice from his muleteer in Paros. Bent writes:

The Pariotes look down on their neighbours with supreme contempt and call them kouroúnai (κουρούναι), or crows … and my interest was excited about the crows into whose nest we were about to deposit ourselves; but, as it turned out, we found our home for three weeks at Antiparos, not amongst the crows, but in the hospitable nest of the Swans — two English brothers, who work calamine mines on this island, and who not only assisted us in our digging operations, but gave us the rest that we much needed.

Mabel’s chronicle echoes Bent’s endorsement of their new-found friends and tells us of a conversation, on that first night, which would spark Bent’s interest and bring the travellers back to Antiparos for a longer stay just a few weeks later. Mabel writes of that first visit:

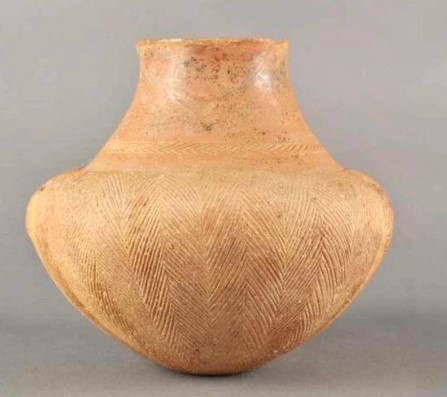

Rode 1 1/2 hour to the nearest point to Antiparos carrying only our night things and a card of introduction from Mr. Binney for Mr. R. Swan who has a calamine mine on this island. Crossed in about 10 minutes. Found the population all enjoying the feast of St. Nikoloas who replaces Neptune. At one house I was obliged to join in the syrtos holding 2 handkerchiefs. We sent a messenger to Mr. Swan and knowing he would take 3 hours to return, rode to meet him. Met Mr. Swan who more than fulfilled our warmest hopes. He took us to his house, and after resting told us that in making a road he had come upon a lot of graves and found a marble cup, broken etc. So, we manifesting a great wish to dig too, he got men and we opened 4. They were lined and paved with slabs of stone and the people must have been doubled up in them, they were so small; we only found, besides bones, 2 very rough marble symbols of men and women, little flat things and some broken pottery.

So, in early February 1884, the couple returned for a longer run with a script which saw Bent excavating 40 ancient graves, yielding a plethora of unique finds. Those finds, now in the British Museum, essentially wrote the text-book for our understanding of early Cycladic culture.

Following the plot

Although Bent’s work during his 2 weeks on Antiparos led to his being recognised as a serious archaeologist, we know little about his day-to-day activities. Unusually, Mabel’s chronicles do not give us as much information as on some of the less important islands they visited.

We do know he left for a visit to Amorgos for a week, leaving Mabel with the Swans to recover from a bout of ill health. We also know from Bent’s book, The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks, that he took a day off to go fishing on St. Simeon’s Day note 4 when his workers refused to work on the Saint’s day. Even on his day off, he used the time to gather material for a magazine article entitled ‘Fishing in Greek Waters‘, which he later incorporated into the book. You can read the gripping story in The Cyclades book or in the free online ebook, In Greek Waters, on our sister site.

Bent and Mabel both mention that they stayed at Robert Swan’s house but give us few clues as to exactly where that house was. We know his first excavation was at the suggestion of Robert Swan who ‘in making a road he had come upon a lot of graves and found a marble cup, broken etc.‘ But where was that road and hence the excavation site?

The following sections try to answer these questions. These ‘answers’ are not definitive and are hypothetical assertions based on researching the island’s recent industrial history, speaking with local people and visiting potential sites. We welcome discussion and further information from any source and will update this article as new information becomes available or any of the assertions are proved to be false.

We have one ‘hard’ piece of evidence. Bent tells us that his first excavation site was “on the slope of the mountain, about a mile above the spot where the houses were”. He saw the ‘houses’ submerged in the narrow stretch of sea between the island of Tsimintiri and the southern shore of Antiparos near present-day Aghios Georgios. Using this fact, I’ve tried to bring together discrete pieces of Bent’s and Mabel’s writings and local exploration and research to come up with the most probable positioning for all three of our sort-after locations.

1. The Swans’ house

The location of the Swans’ house is key to finding Bent’s initial exploratory dig site in December 1883 and his subsequent, more extensive digs a few weeks later.

Theodore and Mabel Bent had been staying in Paroikia in Paros, and Bent tells us that they left early for the journey to Antiparos: “On the next morning early we started for Antiparos, a desolate ride of two hours to the point where the ferry boat takes passengers across.” Mabel’s chronicle contradicts Bent’s timing: “Rode 1½ hour to the nearest point to Antiparos”.

Mabel writes that Swan’s house was a 90-minute ride (in one direction) from Antiparos town where the ferry landed the couple: “We sent a messenger to Mr. Swan and knowing he would take 3 hours to return, rode to meet him. … He took us to his house, and after resting told us that in making a road he had come upon a lot of graves and found a marble cup, broken etc. So, we manifesting a great wish to dig too, he got men and we opened 4.”

These events all occured within the same day so, timing, and Bent’s subsequent description of the location of the dig site, pins down the approximate location of the house.

Mabel noted in her diary that they visited Antiparos on December 18, however, that date needs to be clarified. Bent says it was St. Nicholas’ Day (December 6). With the 12 days old-style/new-style calendar shift that Mabel always factored in, it would confirm Mabel’s date of December 18 note 5 . In 2018 on that day in Greece, there were 9 hours and 32 minutes of daylight with the sun rising at 08:35 and setting at 18:07. The actual times would vary slightly according to the longitude of a specific location, but the interval would be the same. Over the intervening 134 years, a few seconds of drift may have to be factored in. Also, without further research, it’s not certain that there was a universal Greek time or whether, more likely, it changed with longitude, and, the relationship between the ‘clock time’ and sunrise may not have been as now. However, this is all self-balancing and we still end up with around 9:30 hours of daylight.

We have to assume that Bent and Mabel would not be travelling by mule in the dark. Adding up Mabel’s chronicled day should give us the amount of time remaining for Bent’s exploratory dig:

- Paroikia to Pounda 1:30 (Mabel’s lower reckoning)

- Awaiting the boat to come from Antiparos 0:15

- Crossing 0:15

- Festivities (Mabel tells us they joined in) 0:30

- Ride to the Swans’ house 1:30 (although Bent tells us it was 2 hours)

- Resting at the Swans’ house (say) 1:00

This totals, conservatively, 5:00 hours, leaving just 4:30 hours for Swan to organise the men for digging, to travel to the site from Swan’s house, excavate 4 graves and travel back. Therefore, the site must have been VERY close to the Swans’ house.

Bent tells us, almost exactly, where the dig site was:

A rock in the sea between Antiparos and the adjacent uninhabited island of Despotiko is covered with graves, and another islet is called Cemeteri, from the graves on it. The islands of Despotiko and Antiparos were once joined by a tongue of land, which was washed away by the encroachment of the sea on the northern side; and in the shallow water of the bay, between the islands, I was pointed out traces of ancient dwellings … I was able to discern a well filled up with sand, an oven, and a small square house. … A clever fisherman, who knows every inch of the bay, told me that pottery similar to that I found in the graves was very plentiful at the bottom of the sea near the houses. It is on the slope of the mountain, about a mile above the spot where the houses were, that an extensive graveyard exists. It is not unlikely that the submerged houses form the town of which this was the necropolis.

Taking our assertion of the proximity of Swan’s house to Bent’s initial dig site, would locate the house to be 1 to 2 kms north of the present-day village of Aghios Georgios.

While researching another, unconnected, story in Aghios Georgios, I mentioned my Bent search to a local man, Tassos G… . This conversation threw up a tantalising possible candidate for the Swans’ house. “If you follow that track up and over the hill, you’ll come to a building which was owned by a French mining company” he said. “It’s used as a farm building now but it’s not an average local house – look at the stonework”.

After leaving Tassos’ house, I immediately took the track he’d indicated. The house he’d described was indeed more high-status than the usual farm building. It’s now being used to store hay. There are some additional buildings around it with another largish building across the track.

Part of the house has been demolished and the existing walls represent approximately two thirds of the original length of the house.

The stones forming the walls are of a regular shape and have either been cut or carefully selected; by comparion, the other large building mentioned, on the opposite side of the track, is of a much rougher construction.

An element of decorative embellishment can be seen in the door and window lintels, being curved and formed from stones rather than a simple straight piece of timber. All the internal walls were at one time rendered.

While looking around the site, I noticed SOMETHING QUITE AMAZING – but more of that a little later.

The track continues on up the hillside and eventually reaches a large mining site to the north of Mount Profitis Ilias at Koutsoulies. Could this road have been the one which Mabel writes about: “He took us to his house, and after resting told us that in making a road he had come upon a lot of graves.”

Further investigation yielded more ‘evidence’ as set out in the following sections.

2. The calamine mine

Calamine is a combination of zinc oxide and ferric oxide. Read more about calamine.

The Municipality of Antiparos’ official website states: “Mining activity on the island began in 1873, when the state ceded the exploitation rights to these deposits to the Elliniki Metalleftiki Etaireia [Greek Mining Company]” note 6

Another account of mining activity tells us: “Limonite ore, from which iron containing pockets of azurite and zinc are extracted, can be found on the western slopes of Profitis Ilias of Antiparos. The Greek Mining Company began mining operations in 1873 and started mining zinc from Kaki Skala. In 1900 the mines were taken over by the French Company of Lavrion” note 7

This second account mentioning the French Company of Lavrion would seem to tie in with Tassos’ statement about the house having been owned by a French mining company.

In searching for the calamine mine, I was initially drawn to the site of the mines at Koutsoulies, however, being on the north slope of Profitis Ilias somewhat casts doubt on this being the site of Swan’s mine. Additionally, the track from the house to those mines twists and turns around the folds of the mountain, probably a distance of 8-10 kms or so. Why would Swan live so far from the place of his work? The house indicated by Tassos is not in a ‘desirable’ location: it’s not in a village, or a town, it’s not by the sea. There had to be another reason why the mining company had built the house at that location. The calamine mine just had to be closer to the house, and, remember, in a very short space of time, Swan had gathered up a team of men to help Bent on his initial exploratory dig.

A kilometre further on from the house, the track passes above a ravine showing clear signs of quarrying with heaps of mining spoil to be seen, not yet fully overgrown. A kilometre further on, a track leads down to the ravine bed and closer examination of the quarry can be made. To the untrained eye, some of the loose spoil looks iron-based (ferric) with rust-red patches revealing its presence – a possible indication of calamine. The extent of the quarry can be clearly seen on the map in this article when switched to satellite view.

Bent writes of the local man named Zeppo:

On the opposite side of the island to the village of Antiparos, about two hours on muleback over the mountains, are a few scattered houses gathered round the calamine mines. Here we were staying, close to our graveyard, and here Zeppo has his store and dispenses his goods to the miners.

So, Bent’s writings would seem to support our assertion that the calamine mines were close to Swan’s house and hence his initial dig site. Were those “few scattered houses gathered round the calamine mine” the ‘farm’ buildings I’d seen?

Bent’s statement in relation to calamine extraction, “I could find no trace of any ancient works here [Antiparos]“, supports the premise that the quarry near to the Swan’s house was from the modern era.

3. Bent’s excavation sites

Bent was relatively restrained in his excavations on Antiparos, given the number of sites he was told about, and one would like to think that he thought he’d leave some for future generations of archaeologists. He writes:

I was induced to dig at Antiparos because I was shown extensive graveyards there. Of these I visited no less than four on the island itself, and heard from natives of the existence of others in parts of the island I did not visit.

Of the four sites he visited, he excavated only two: “I opened some forty graves from two of the graveyards”. Just these two sites yielded a vast number of finds, all of which are now in the British Museum (view the objects in the British Museum).

Subsequent excavations by Tsountas and Dr. Zozi yielded a smaller number of finds, some of which can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens (see earlier image).

The first site

I’ve tried to establish earlier that Bent’s first excavation site was close to the Swans’ house and close to the calamine mine.

The fortuitous conversation with Tassos about the French mining company house led me to explore the track he’d pointed out to me.

I found the house and, on walking around the immediate area, I saw to my utter amazement, just across the track from the house, some fairly recent excavations of, what looked like, graves identical to those described by Bent. How could this possibly be? Bent’s original excavations would have eroded or been overgrown over the past 130 years, so somebody had been excavating here recently.

Back at the Bent Archive base, on receiving my report of finding these new excavations, the team started scouring the Internet for any recent references to Bent’s excavations on Antiparos. They came upon an advance notice of a lecture note 8 which was to have been given to The Archaeological Society at Athens in December 2018 – just 9 months previously. The presenter was to be Dr Zozi Papadopoulou. A précis of the lecture stated: “In recent investigations by the Ephoria of Antiquities for the Cyclades, the Krassades site was relocated [located once more] and a cluster of graves, some undisturbed, were explored.”

With no contact details for Dr. Zozi Papadopoulou, the Bent Archive sent an email to Demetris Athanasoulis, Director of The Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, who forwarded the message to Dr. Zozi, to which she replied:

The site of Krassades has been located in the last decade about 1km north of the modern settlement of Ag. Georgios in Antiparos. We actually excavate part of the cemetery with very interesting findings. I am sending a link directing you to one of my articles with informative photos included (pp 357-359). The “southeast site” you mentioned has not been identified yet…

Dr. Zozi’s reply arrived after I’d left Antiparos. The information in the article which she references note 9 in her email looks to be extremely interesting and, armed with this new information, a return visit beckons soon after travel is permitted following the current (2020/21) pandemic.

Her reply confirmed what I’d deduced from the lines of Bent’s book and Mabel’s chronicles, and from my researches on Antiparos – the exact location of Bent’s first excavation site, the location of the Swans’ house and the location of the calamine mine.

The second site

Neither Bent nor Mabel provide us with any precise information on where the second site was located, although Jörg Rambach in Early Cycladic Sculpture in Context (Marthari et al. (eds), Oxford, 2017, ch. 7) suggests in the area of Apantima or Ag. Sostis. Bent only gives us two vague geographic references.

One reference tells us that it was “to the south-east of the island”. This could lead us to believe that it was somewhere on the peninsula, south or west, of the present-day village of Soros.

The other reference provides the information: “In Antiparos the inhabitants had their obsidian close at hand, for a hill about a mile from the south-eastern graveyard is covered with it.”

SO – a project for a future (very long) visit to Antiparos – find an obsidian needle in an obsidian haystack in the south-east of the island!

Dr. Zozi’s reply seems to confirm that the location of Bent’s second site is still unknown:

The “southeast site” you mentioned has not been identified yet.

Epilogue

As with any complex plot, the individual players each add their part to the overall story and serendipity often plays a major role.

In 1884, Bent published his article, Researches Among the Cyclades in the Journal of Hellenic Studies note 10 , describing his excavations on Antiparos. Around the same time, he was also writing his book, The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks note 11 , in which he included much of the text of the previously published article, save for a short appendix, Notes on an Ancient Grecian Skull. Aside from this appendix, the text of the article and the book are largely identical with the notable exception of the first paragraph. In the article he writes:

It is first of all necessary to state why I chose Antiparos as a basis for investigation on this point: firstly, because during historic times…

The version in his book contradicts that of the article:

On ascertaining the existence of extensive prehistoric remains at Antiparos I felt that it would be a satisfactory spot for making investigations — first, because during historic times…

Both versions continue identically and both contain the second paragraph starting:

Secondly, I was induced to dig at Antiparos because I was shown extensive graveyards there.

In the article version, Bent is suggesting that he chose Antiparos in advance because, from the considerations he sets out, he foresaw that he might find remains there, whereas, in the book version, his considerations were only entered into following the meeting with Robert Swan and his excavations on that first brief visit.

Although Bent was always on the look-out for potential dig sites wherever he roamed, one might assume, given that he only intended to stay overnight, that his reason for visiting Antiparos was other than archaeology. It would seem that he came as a ‘tourist’ to visit “the celebrated grotto” for its medieval historical interest, about which visit he wrote extensively in his book. His archaeological interests lay much further back in history and, for Bent, Antiparos was “a place without a history.”

It can be said therefore that the discovery of the Krassades site was a result of two supreme examples of serendipity. Firstly, in Robert Swan’s stumbling upon the graveyard while making the road to the calamine mines and, secondly, in Swan’s mention of the graves on that first night, without which, Bent might never have proceeded to dig on Antiparos. Maybe it was always in Swan’s mind to mention his finding of the graves, and Mabel’s account makes it sound as though the subject might have been on his agenda: “He took us to his house, and after resting told us that in making a road he had come upon a lot of graves and found a marble cup, broken etc.”

Robert Binney, the British Consul in Syros, played his part well in bringing Swan and Bent together.

We don’t know for sure, but it would seem that Swan made no monetary gain from bringing the site of the graves to Bent’s attention, nor for assisting him during the Bents’ 3-week stay on the island (although Bent himself stayed only for 2 weeks, leaving Mabel with the Swan brothers on the third week, suffering from poor health). Robert Swan and the Bents became close friends from that point on and Swan later drew some element of fame from accompanying Bent on his expedition to Great Zimbabwe.

Bent, of course, gained the greatest applause and accolades. As an established author of books and journal articles, and as a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, he had all the right contacts to finally make his name as an archaeologist, aided by his sale to the British Museum of the Antiparos finds, his article Researches Among the Cyclades, published in 1884 in the Journal of Hellenic Studies, note 12 and the publication of his best-selling book The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks note 13 in 1885.

Christos Tsountas played a key ‘linking’ role, some 15 years after Bent’s excavations. Probably working from Bent’s writings, and being able to find local people with personal recollections of his visit in 1884, he identified Bent’s excavation site and named it as Krassades. He was also the first to methodically excavate the site using sound archaeological practices.

That ‘link’ provided by Tsountas, was picked up over 100 years later by Dr. Zozi Papadopoulou who successfully located, once again, the Krassades site and has produced detailed and modern analysis of older parts of the site as well as new areas of interest. Her work on the site continues.

The last words of the script should rightly be spoken by Dr. Zozi, to rapturous applause from the audience:

“May I take the opportunity to also express the wish that the skeletal remains come back to the island.”

Should Dr. Zozi’s wish be granted, expect to see a sequel to this story, possibly entitled ‘Of Crows and Swans and Calamine – A Wish Come True’.

We leave it to you, the audience, to make up your own mind, from the script we’ve compiled, as to who should share the applause in the “Archaeology Theatre of Antiparos”.

Critical reviews

This section sets out discussions and new information on the subject of the precise locations of Bent’s excavation sites and Robert Swan’s house.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this articleNotes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

Return from Note 8

Return from Note 9

Return from Note 10

Return from Note 11

Return from Note 12

Return from Note 13

POSTSCRIPTS

We are delighted to add (January 2024) that the skeletal material recovered by the Bents from Antiparos in the winter of 1883/4 and now in the Natural History Museum, London, has recently been assessed by Laura Ortiz Guerrero in “Osteological analysis of the Early Bronze Age human remains excavated from Antiparos in the 19th century” (Unpublished Master’s Dissertation, University of Sheffield, Department of Archaeology, 2023).

Present whereabouts unknown, but presumably in the former Musée Archéologique De Charleroi, a most interesting group of four vases (two stone, two clay) was removed from Antiparos after 1850 and entered the collection of the industrialist Valère Mabille (1840-1909), who later presented them to the ‘Société paléontologique et archéologique de l’arrondissement judiciaire de Charleroi’. One of the vessels is nearly identical to a jar removed by Bent from the sprawling site at Krassades and sold later to the British Museum (1884,1213.42). It is very possible that the four Charleroi pots are from the site Bent was to explore in 1883/4, and were looted during the French mining operations that were ongoing there before the Bents arrived. One of the pots, it seems, contained some skeletal material, possibly not yet analysed; the bones Bent brought back from the Krassades site are currently being studied. Such examples from Antiparos are very rare. The echo of Mabel in Mabille does not go unheard. (Ch. Delvoye, Quatre vases préhelléniques du musée archéologique de Charleroi, L’Antiquité Classique, 1947, 47-58)