A throwaway line in Mabel Bent’s ‘Chronicle’ of Monday, January 25th, 1897, written off the beaten track in Socotra, arouses curiosity and links us tangentially to her husband’s friend, Nigel Gresley: “All the booted portion of the party are now in anxiety about their foot gear, as to how it will hold out till Tamarida. We apply the gums of various trees to retard consumption. At last, instead of going over a precipice we (turned to the left) reached a river and on the other side of that we encamped… I was not tired. I am sure our legs will be in good training for our bicycles [our italics].” (Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 3, p. 300)

Bicycles? Yes indeed… The Bents were bikers by the 1890s, if not before.

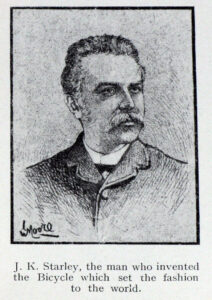

Around the early 1880s, soon after the Bents’ wedding in fact, bike designers were looking for ways of getting their riders nearer the ground (think ‘Penny-farthing’ here), i.e. safer. It was a British engineer, it seems, who cracked the problem – John Kemp Starley (1855-1901), with his 1885 ‘safety’ bicycle (coincidentally the year Theodore was also making a name for himself with his famous guidebook on the Cyclades). A revolutionary feature of this new invention was that now both wheels (with pneumatic tyres ) could be the same size, thanks to its chain drive mechanism.

The Starley ‘Rover’ (the polymath designer was involved with the founding of this famous brand) and other models soon started a craze for biking, and thousands of clubs sprang up all over Europe. Also revolutionary was the speedy acceptance of biking by women (suitably attired), and these bike clubs can be said to have played a proud and early role in gender equality! The only reference we have so far by Theodore himself to the sport comes in a letter of 13 September 1896 to the renowned cartographer H.R. Mill, from the house of Bent’s Irish in-laws in Co. Carlow: “We are having it miserably wet over here and biking is at a discount” (Mill Correspondence, RGS RGS/CB7/Bent, T&M).

But a few weeks later, in England once more, the clouds had mostly blown away and Bent was back in the saddle – this time not with Mabel (and we don’t have her opinion on this separation), but with his very old friend the Rev. Nigel Walsingham Gresley of Dursley, Gloucestershire (UK). Cairo to Cape Town (Bent knew them both)? No. Aden to Shibam (ditto)? No. What we have is an energetic week in gentrified East Anglia, eastern England – eating, drinking, fishing, sketching, brass-rubbing, and church-going.

Clearly Bent’s trip with his old school and college friend was well prepared in advance, as there were prearranged stops to visit some of Theodore’s acquaintances, including the great novelist Rider Haggard (fellow enthusiast for Great Zimbabwe) and Sir Elwin and Lady Palmer, the former at the time was Financial Secretary to the Khedive in Egypt. In the record of the tour, we read that the friends ‘dined’ with the Palmers, raising the question of clothes! Gresley packed his fishing rod it appears, and what else did they pack for a week and how was it all carried? There are old photographs of fardels strapped to the fronts and backs of bikes, and others of knapsacks.

The map below itemizes where they lay their weary selves after each day’s ride and the major sights they took in along the way. East Anglia comprises the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, the name deriving “from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a tribe whose name originated in Anglia, in what is now northern Germany”, as Wikipedia informs us. In Bent’s day, as now, the region was a most pleasant recreational area – the location of the brisk Norfolk Broads, the birthplace of the great Nelson, and the site of a royal residence at Sandringham, among many other attractions.

We don’t have the actual dates of this biking ‘week in East Anglia’, but it must have been the autumn of 1896. Gresley’s (privately) published account is dated October 28, 1896, and it informs that the pair “starting from Dursley one Monday morning” reached Norwich that night by train; the following Tuesday they caught the midday train from King’s Lynn back to London. Sadly we don’t know what bikes they had, but, interestingly, Dursley later had its own bicycle factory! As they made several boat journeys during the week (in this watery landscape of lakes and twisty rivers – the Waveney, Bure, and Ant), it is not easy to estimate the miles they covered, and of course we have no way of knowing which roads they took then, but it must have been over the 200 miles Gresley claims (and where he makes specific references, or the routes seem relatively clear, a distance in miles has been inserted into his text.)

As for the cost of a bike in those days (1890), we are talking £12 – £20; this seems most reasonable, but remember a pound then would cost you £50 now – so for your new bike: £600-£1000 – rather like today.

And a glance at any map of Suffolk and Norfolk will tell you how labyrinthine the area can be. What maps did our tourists take one wonders? We know Bent had his expedition maps prepared for him by the famous Edward Stanford of Charing Cross. Perhaps from them they ordered a set of the beautiful Ordnance Survey One-Inch maps of England and Wales (the Revised New Series of 1892-1908), a crucial feature of which is the word INN, found in most villages! As for how many times we would have seen the tourists’ bikes propped up against a thatched pub we are not apprised, but opening hours would have been observed no doubt: “… an uncommonly good luncheon of sausages, fried potatoes, and excellent cheese and butter (it is astonishing how hungry bicycling and sight-seeing make one!)”, writes Gresley.

During Gresley’s tale, one can imagine Theodore Bent chatting away, as the bike wheels click, of the lands and landscapes he had passed through over the last twenty years – Africa, Arabia, Persia, Ethiopia, the Sudan – and what a contrast to the benign byways of Norfolk and Suffolk. Of Bent’s cycling chum, the Rev. Nigel Walsingham Gresley, we know not much, other than what a few online references can provide (and should you have a photograph of him please let us know). He was born in 1850, probably in Ashby de la Zouche, and attended Repton School, beginning his friendship with Theodore Bent there. His father was a keen amateur archaeologist. He took an MA from Exeter College, Oxford (Bent was at Wadham). Having several ecclesiastical roles, he was rural dean of Dursley, Glos., at the time of this bike tour of East Anglia with Bent. He married Jane Drummond in 1878 (the year after the Bents’ nuptials). He died in 1909. There is no doubting he was a close and trusted friend of Theodore’s, being left £1000 in the latter’s will in 1897, tragically just a few months following the carefree tour of England’s eastern counties, which we are to let you read any minute now.

WikiTree appears to have much interesting information on the Gresley family, including that they married into the venerable Italian di Langosco dynasty. In the Preface to his monograph on Genoa, Bent thanks “the Contessa C. di Langosco (née Gresley), for… valuable assistance in aiding my research” (Genoa, how the Republic rose and fell, London, 1881, p.vi).

Jerome K. Jerome published Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) in 1889, and N. Walsingham Gresley peddled after the former, alas without the critical acclaim (and justly so), with his A Week on Wheels in East Anglia: Dedicated to the Cyclists of Dursley, a mere seven years later – you can spot the similarities, only for three men, change to two, and boat becomes bike… there is no dog, of course…never was.

“A Week on Wheels in East Anglia: Dedicated to the Cyclists of Dursley”

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article