Reproduced from: The Gentlewoman – The Illustrated Weekly Journal for Gentlewomen, No. 175, Vol. VII, Saturday, November 11, 1893, pages 621-622.

Theodore and Mabel Bent are being interviewed by the editor of The Gentlewoman, Joseph Snell Wood, Autumn, 1893, as the leaves in London’s Hyde Park are changing colour…

One can hardly realise what London would be if suddenly robbed of “The Park”, as we familiarly term it; for without doubt it plays an important part in social life during the season. Coaching and four-in-hand meets, church parade, “The Row”, with its endless line of carriages – are not all these functions indelibly associated with Hyde Park, and where else in the great metropolis could so suitable rendezvous be found?

Such were my thoughts as I strolled across from Albert Gate to the Marble Arch en route to the town house of those distinguished travellers, Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent; for although for a great portion of the year they may wander far from the haunts of civilisation, the commencement of the season generally finds them at 13, Great Cumberland-place. Even in the hall you see evidences of their journeys, for strange Persian plaques hang there and all up the staircase, where also I notice clever water-colour sketches done by Mr. Bent in almost every quarter of the globe. But the travellers are not dependent on Mr. Bent’s brush to illustrate their journeys, as Mrs. Bent is an excellent photographer, and never leaves home without her camera. Often finding a difficulty in developing photos. when in out-of-the-way regions, she designed an apparatus for the purpose, and amongst her portraits a group of African chiefs is conspicuous, their smiling faces showing they evidently appreciated the attention. I am also interested in a photograph of the Greek servant who accompanies Mr. and Mrs. Bent in their travels. He is a very superior man, intelligent, trustworthy, and devoted to his master and mistress, and when they return to England reluctantly leaves them and goes back to his farm until it is time to rejoin them.

But before giving what must of necessity be a brief account of their journeyings, I ought to say that Mrs. Bent is a daughter of the late Mr. Hall-Dare of Newtonbarry, co. Wexford, and Theydon Bois, Essex, and her girlhood was chiefly spent in Ireland, where she lived a healthy out-of-door life. She was born at Beau Parc, co. Meath, her grand-father’s, Mr. Lambart’s home. Before she was married she travelled in many countries including Spain and Italy, and met her husband in the Arctic region – i.e., Norway; from her earliest years having a wish to see those distant lands where the ordinary traveller fears to tread, “And how fortunate that my husband’s tastes should be exactly the same as my own,” said Mrs. Bent, as we talked of the days when she had no idea her wishes would be so fully gratified.

As a member of an old and influential Irish family, Mrs. Bent is naturally interested in the politics of her country, and, being a staunch adherent of the Conservative party, has joined the movement against Home Rule. She is on the Ladies’ Grand Council of the Primrose League, and also interests herself in the Association for Distressed Irish Ladies. A sale of work in aid of this deserving charity was held at 13, Great Cumberland-place in June, when Mrs. Bent kindly gave up all her sitting-rooms for the purpose, and also had an exhibition of the curiosities brought from Abyssinia.

Some of these things have since been presented to the British Museum, but she shows me some effective embroideries done on a soft white cotton fabric, resembling lint of a firm and fine texture. She has the complete costume of an Abyssinian woman made of it and consisting of two garments, a pair of trousers fitting tightly round the ankles, and a long loose overdress to match, lavishly worked round the neck and down the tapering sleeves, which are so tiny at the ends one can hardly imagine a woman’s hand getting through the cuffs. However, Mrs. Bent explains that the Abyssinians are a slender people, and the feminine portion of the population have exceedingly small hands and wrists. She also points out an Abyssinian chair, low and broad, and irregular in shape, the seat of plaited leather and the back carved wood.

Presently my attention is directed to the hammock which is the only bed Mrs. Bent ever has when abroad. It is slung on short poles (to one of which her revolver case is attached), and, though by no means a luxurious couch, she assures me custom enables her to sleep quite comfortably in it. After a while she brings me into the museum, where her greatest treasures are stored on brackets and in cabinets, and under the stained-glass window stands an ancient Greek tomb having an inscription to the memory of “Theodore”. It was found by Mr. and Mrs. Bent when searching for antiquities, and is now a receptacle for ferns.

Here, too, I see a rare statue of Cybele and some graceful vases and other relics. On the staircase outside a Persian spear and shield, the gift of a native Sheik, is a striking object; and, returning to the drawing-rooms, I note an immense goblet, from the country of the Shah, and engraved with the remark that “It is good to sit in the shade with friends and drink wine,” and truly the maker allowed for a goodly supply!

Another insight into Persian customs is gained by looking at several exquisite blue and gold china birds which are used to hold perfume, and when a guest whom the host delights to honour enters a house, he takes a bird up, and, holding it by the long tail, pours the scent over the favoured person.

One must admire almost equally the bracket of inlaid Persian wood on which the birds now repose, mirrors from Kattam ingeniously inserted at the sides showing them off to advantage. However, visitors of artistic proclivities find much to admire besides these curiosities, and a magnificent collection of old English china would especially delight the connoisseur. Some of it in a roomy and handsome inlaid cabinet came from Mrs. Bent’s old home, for her father was an indefatigable collector, and his daughter has inherited a mild form of “china mania”. In fact, all over the house one sees costly and beautiful specimens, and the drawing-room walls are nearly covered with a delightful combination of china, rare prints, paintings by eminent artists, antique embroideries, and, in short, a miscellaneous array of bric-a-brac which gives them a pleasing individuality.

These rooms – a suite of three – contain a unique pair of curtains, also portiere, brought by Mrs. Bent from the Turko-Grecian Isles. They are a mass of thick coloured embroidery worked on thin silk, and are looped up with Servian brasses and Mashonaland fossil shells strung to form girdles. Having carefully examined them, I pass on to a carved oak writing-table which belonged to Mr. Bent’s great-great-grandfather, miniatures of his ancestors surmounting it, and am soon intent upon the contents of a little glass-cased table containing many quaint knick-knacks.

But were I to enumerate all the uncommon things in Mrs. Bent’s house, it would require a great deal more space than could be allowed, so I must conclude with the two pictures found in the cave of the Apocalypse at Patmos, which hang amid the old Italian painting in the dining-room.

It was in 1884 [it was the winter of 1882/3 – ed.] that Mr. and Mrs. Bent began their important antiquarian work, and starting from Athens, visited Tenos, Samos, Chios, and Mitylene; next year going through the twenty-two Cyclades Isles, digging at Antiparos, from whence they brought back contributions to the British Museum. During her first visit to Greece Mrs. Bent had not mastered the language, and the people – with unsophisticated candour – said she was very nice, but dumb! Three years later she revisited them and conversed fluently, much to their surprise. She is, indeed, a remarkable linguist, speaking a variety of tongues (Eastern and European), and readily acquires the languages of the countries she is in. Mr. Bent is similarly gifted, and thus they have greater facilities of studying the people amongst whom they sojourn, and, needless to add, some of their experiences are most amusing and instructive.

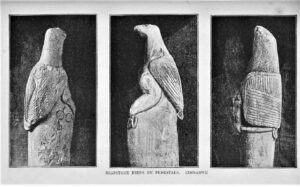

In 1885 [it was 1886 – ed.], Samos, Patmos, and many other islands of the Sporades, in 1886 [it was 1885 – ed.], Egypt, Rhodes, and Karpathos, were chosen as the scene of Mr. and Mrs. Bent’s research, when they returned all the way by sea, bringing with them twenty-four cases as the result of their work. In 1887, they went to Thasos, an Egyptian island near Thrace, where they found statues which the Khedive, through Sir E. Baring, gave them permission to take away for the British Museum. Unfortunately the statues were stolen by the Turks, and no English effort was made to recover them, much to the disappointment of the discoverers, who came to England by High Macedonia and Servia. Part of the next year was spent in a sailing cruise along the south coast of Lycia, digging whenever they landed and with good results. But, wishing to go still further afield, they started in 1889 for Bahrein, Persian Gulf, where they devoted a considerable time to “digging”; from thence going across Persia and over the Caucasus, attended by a special escort from the Shah.

Mrs. Bent mentions the astonishment of the natives when she paid for the supplies got at the places en route, a fact which gives one an idea how things are managed under the rule of his dusky Majesty [sic]. In 1890, soon after this tour, the travellers went to Cilicia, where they made several important discoveries, particularly Olba and the Korycian Cave. But the now famous expedition to Mashonaland, begun the next January, 1891, was destined to eclipse all former journeys, and even those not in sympathy with antiquarian pursuits must admire the intrepid pair who braved many dangers during their self-imposed task.

Starting from Cape Town, through Bechuanaland, they reached the ruins of Zimbabwe in June, and successfully accomplishing their mission, and having been through a pathless country to the Sabi river, they retraced their steps via Beira, and reached England in January, 1893 [it was 1892 – ed.]. The commencement of 1893 found the indefatigable travellers in Abyssinia, and since their return in April, many absurd tales have circulated about the events that occurred there. As a matter of fact they were not threatened with execution, or any of the horrors rumour was responsible for. There is no doubt, though, that their position was a dangerous one, by reason of the disturbed state of the country, and the wish of the inhabitants to keep them in, so to speak, a kind of friendly captivity. This was, however, from liking rather than enmity, and even the escort which Mr. Bent at length obtained endeavoured to dissuade him from leaving the place.

Having twice been defeated in attempts to get away, the situation became decidedly unpleasant; and hearing troops were pouring in and there was a prospect of serious fighting, Mr. Bent said they must make a strong effort to escape. Mrs. Bent at the moment was engaged in photography, and, nothing daunted by her surroundings, actually finished the photos. before leaving the hut. An Italian officer and four hundred soldiers were sent to rescue them. Watching for a favourable opportunity, the little party mounted their mules and several days’ riding brought them safely to the coast, where they embarked for England.

Chatting about her life abroad, Mrs. Bent says habit has made “roughing it” second nature, and when the tents are closed at nightfall, and she gets into her hammock among the furniture so long in use, it is hard to believe the tent is not a fixed abode which never moves.

Want of water was perhaps her greatest privation, for in some places the supply had to be so carefully husbanded that baths were an impossible luxury, and even tea was sometimes impracticable.

As the recent verdict of the Royal Geographical Society against admitting ladies has been a topic freely discussed both socially and in the papers in connection with Mrs. Bent’s name, I think this article would be incomplete without saying that she (to quote her own words) “has no yearning to be a Fellow”, and the benefits already accorded by the Society are sufficient for her modest requirements. She is very reticent about her share in her husband’s discoveries, and could never put herself forward in any way. Her manner, too, is singularly winning, and, united to unusual conversational powers, makes her a delightful companion, with whom time seems to fly, especially when she describes, in her own graphic way, some of the incidents connected with her travels.

Apropos of this, an illustrated book on Abyssinia by Mr. Bent (written by request) will soon be published, and is sure to be as eagerly read as his former works on “The Cyclades”, and “Mashonaland”, which rapidly ran into several editions. South Arabia is to be the next country visited by Mr. and Mrs. Bent, who start on their journey a few days after these lines appear in print, having spent the autumn at their country house, Sutton Hall, in Cheshire.

As I say good-bye and bon voyage, it is with the hope of next year meeting one of the most notable and charming women of the day, and hearing that the Arabian tour has been as successful as all the previous journeys undertaken by Mr. and Mrs. Bent.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article