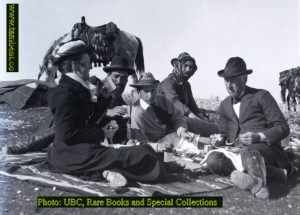

This extremely rare photograph shows Mabel Bent taking tea with Moses Cotsworth and party in the Palestinian hinterland in 1900/1 (Moses Cotsworth collection, unknown photographer. Photo reproduced with the kind permission of Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia).

This extremely rare photograph shows Mabel Bent taking tea with Moses Cotsworth and party in the Palestinian hinterland in 1900/1 (Moses Cotsworth collection, unknown photographer. Photo reproduced with the kind permission of Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia).

“Dear Sir William…Thank you for sending me the flower pictures. I like them very much. Of course I know there is nothing to find in Palestine that is new. I was there the winter before last and camped out by myself 10 weeks in Moab and Haura. I had my own tents and no dragoman. This winter I only got to Jebel Usdum and arrived in Jerusalem with a broken leg, my horse having fallen on me in the wilderness of Judea. My sister Mrs. Bagenal came from Ireland and fetched me from the hospital where I was for 7 weeks. I cannot walk yet but am getting on well and my leg is quite straight and long I am thankful to say…Yours truly Mabel V.A. Bent” (Letter from Mabel to Thiselton-Dyer, 19 April 1901 (Kew Archives: Directors’ Correspondence)).

Theodore’s death in May 1897 – Jubilee year – deprived Mabel of the focus for her life: the need to be somewhere else remained, but now with whom? And why? Typical of her she made plans immediately to visit Egypt on a ‘Cook’s’ tour in the winter of 1898 and chronicled the trip, ending with a return via Athens. The journey provides the concluding episode in this volume, and the heading she gives it – ‘A lonely useless journey’ – reveals her understandable depression. It makes unhappy reading, contrasting so markedly with her opening thrill of being in Cairo on that first visit with Theodore in 1885.

She wrote no more ‘Chronicles’, or at least there are no more in the archives, and on her return to London set about assembling the monograph her husband never lived to complete on his Arabian theories and researches, many of which sprang from their explorations in Mashonaland in 1891. She completed it in eighteen months: driven on by her loss, and inspired by her notebooks, she could be travelling again with Theodore.

The publication by Mabel of ‘Southern Arabia’ (1900) heralded for its surviving author a slow but inevitable decline and a melancholy sequence of years of loneliness and confusion until her death in 1929.

Still wishing to escape the English weather, Mabel opted to spend several winters in Palestine and Jerusalem. There she made local expeditions, and embroiled herself in troublesome expatriate intrigue and Anglican fundamentalism, and met Gertrude Bell, who informed her parents by letter: ‘I … met … Mrs. Theodore Bent the widow of the Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, a thin stiff little Englishwoman [sic], I don’t like her very much.’ And again two weeks later: ‘I met Mrs. Theodore Bent, but having thrown down the Salaam, as we say in my tongue, I rapidly fled, for I do not like her. She is the sort of woman the refrain of whose conversation is: “You see, I have seen things so much more interesting” or “I have seen so many of these, only bigger and older”… I wonder if Theodore Bent liked her.’

On her second solo trip to Palestine in 1900/01, Mabel joined a caravan to visit some sites referenced in the Scriptures, but inexplicably opted to go off on her own, and so doing fell off her mount and broke her leg; hence the above letter to her friend, the Director at Kew. Gertrude Bell in her diary refers to a talk with Mabel in April 1900, and writes that the latter so far “has only been to Mashetta and Bozrah.”

Now, thanks to help from Anna Cook, the researcher on Moses Cotsworth, we have more information on Mabel’s accident, as recounted by the geologist George Frederick Wright, whose caravan it was that she joined. The (lengthy) extract that follows from his autobiography has probably never seen the light of day since its publication in 1916.

“At Jerusalem we were met by my Old Andover friend, Selah Merrill, then United States consul. His experience in the survey of the country east of the Jordan, and his long residence in Jerusalem, were of great service in our subsequent excursions in Palestine. After visiting Jericho and the region around we planned, under his direction, a trip to the unfrequented south end of the Dead Sea. In this we were joined by Mrs. Theodore Bent, whose extensive travels with her husband in Ethiopia, southern Arabia, and Persia, had not only rendered her famous but fitted her in a peculiar manner to be a congenial and helpful traveling companion. She had her own tent and equipment and her own dragoman, and her presence added greatly to the interest of the trip.

“After stopping a day at Hebron, we passed along the heights till we descended to the shore of the Dead Sea at the north end of Jebel Usdum, through the Wadi Zuweirah. Here we found indications that, during the rainy season, tremendous floods of water rushed down from the heights of southern Palestine, through all the wadies. Such had been the force of the temporary torrents here, that, over a delta pushed out by the stream and covering an area of two or three square miles, frequent boulders a foot or more in diameter had been propelled a long distance over a level surface. At the time of our visit, the height of the water in the Dead Sea was such that it everywhere washed the foot of Salt Mountain (Jebel Usdum), making it impossible for us to walk along the shore…

“Near the mouth of Wadi Zuweirah, we observed a nearly complete section of the 600-foot terrace of fine material, displaying the laminae deposited by successive floods during the high level maintained by the water throughout the Glacial epoch. From these it was clear that this flooded condition continued for several thousand years. On the road along the west shore to Ain Jiddy (En-gedi) we observed (as already indicated) ten or twelve abandoned shore lines, consisting of coarse material where the shore was too steep, and the waves had been too strong to let fine sediment settle.

“From all the evidence at command it appears that, at the climax of the Glacial epoch, the water in this valley rose to an elevation of 1,400 feet above the present level of the Dead Sea, gradually declining thereafter to the 600-foot level, where it remained for a long period, at the close of which it again gradually declined to its present level, uncovering the vast sedimentary deposits which meanwhile had accumulated over the valley of the Jordan, north of Jericho.

“Our ride from Ain Jiddy to Bethlehem was notable in more respects than one. The steep climb (of 4,000 feet) up the ascent from the sea to the summit of the plateau was abrupt enough to make one’s head dizzy. But as the zigzag path brought us to higher and higher levels, the backward view towards the mountains of Moab, and towards both the north and the south end of the Dead Sea, was as enchanting as it was impressive. Across the sea, up the valley of the Arnon, we could see the heights above Aroer and Dibon, and back of El Lisan, the heights about Rabbah and Moab, and. those about Kir of Moab, while the extensive deltas coming into the Dead Sea along the whole shore south of us fully confirmed our inferences concerning their effect in encroaching upon its original evaporating area.

“After passing through the wilderness of Jeruel and past Tekoah, as we were approaching Bethlehem, a little before sundown, the men of our party wished to hurry on to get another sight of the scenes amidst which Christ was born. As Mrs. Bent was already familiar with those scenes, she preferred to come along more slowly with the caravan, and told us to go on without any concern for her safety. But soon after arriving at Bethlehem, the sheik who accompanied our party overtook us, and told us that Mrs. Bent had fallen from her horse and suffered severe injury; whereupon we all started back over the rocky pathway, to render the assistance that seemed to be needed.

“On reaching a point where two paths to Bethlehem separated, we were told by a native that he thought our party had proceeded along the other path from that we had taken, and that it would be found to have already reached its destination before us. We therefore returned to Bethlehem. But, soon after, the dragoman came in great haste, saying that Mrs. Bent had indeed fallen from her horse and broken a limb, and that he had left her unprotected in an open field to await assistance. Again, therefore, but accompanied by six strong natives with a large woolen blanket, on which to convey her, we proceeded to the place where the accident occurred. Here we found her where she had been lying for about two hours under the clear starlight. But, instead of complaining, she averred that it was providential that she had been allowed to rest so long before undertaking the painful journey made necessary by the accident; and that all the while she had been occupied with the thought that she was gazing upon the same constellations in the heavens from which the angel of the Lord had appeared to the shepherds to announce the Saviour’s birth.

“The task of giving her relief was not altogether a simple one. The surrounding rocky pastures did not yield any vegetable growth from which a splint could be made to stiffen the broken leg. An inspiration, however, came to my son, who suggested that we could take her parasol for one side and the sound limb for the other, and with the girdle of one of the men bind them together so that the journey could be effected safely. No sooner said than done. The sufferer was laid upon the blanket and slowly carried to Bethlehem by the strong arms of our native escort. From here she was conveyed by carriage to Jerusalem where we arrived between one and two o’clock in the morning, taking her to the English hospital, of which she had been a liberal patron, and where she was acquainted with all the staff; but, alas! this hospital was established exclusively for Jews, and as she was not one they refused to admit her, advising her to go down to the hospital conducted by German sisters. This, however, she flatly refused to do, declaring that rather than do that she would camp on the steps of the English hospital. At this two of the lady members of the staff, who were her special friends, vacated their room and she was provided for.

“Respecting the sequel, we would simply say that her limb was successfully set, and with cheerful confidence she assured us that she would reach London before we did and that we must be sure to call upon her there. She did indeed reach London before we left the city, but it was on the last day of our stay, and, as our tickets had been purchased for the noon train going to Plymouth, we were unable to accept her invitation to dine that evening. Some years afterwards, however, when visiting the city with Mrs. Wright, we found her at home, and had great enjoyment in repeatedly visiting her and studying the rare collections with which she had filled her house upon returning from the various expeditions in which she had accompanied her artistic husband.

“[Some time later pausing] at Rome, Florence, and Genoa, we entered France through Turin by way of the Mount Cenis tunnel, and, after a short stop in Paris, reached London, where I met again the large circle of geologists and archaeologists who had entertained me on my first visit to England… Returning to London, we engaged passage on a steamer from Southampton, just in time, as before remarked, to miss meeting Mrs. Bent, our unfortunate traveling companion in Palestine.” [From: ‘The Story of my life and work’ by Wright, G. Frederick (George Frederick), 1838-1921; Oberlin, Ohio, Bibliotheca Sacra Company, 1916 (including pages page 324 and 328/29. The link to the book is https://archive.org/stream/ ).

Additional thanks also go to Anna Cook and the Moses Cotsworth Facebook Page

PS: On her stretcher journey to eventual hospitalisation in Jerusalem, Mabel would have shut her eyes and been transported back four years to the last time she was rescued, terribly sick with malaria, east of Aden. Also stretchered to Aden, her husband never survives the ordeal, dying in London a few days after arriving home in 1897. Here are the memories she must have relived in the form of some lines from Mabel’s own diary:

‘I felt quite unable to move or stir but on we must go; we had no water and what we had had the day before was like porter. I could not ride, of course, so they said they would carry me. I was dressed up in a skirt and a jacket, my shoes and stockings, a handkerchief tied on my hair, which was put back by one hairpiece and became a hot wet mat, not to be fought with for many a day to come! Of course I could not use my pith helmet lying down. I lay outside, while my bed was strengthened in various ways with tent pegs and the tent poles tied to it and an awning of blanket made. I dreaded very much the roughness of the road and the unevenness of step of my bearers, but off they set at a rapid pace and kept perfect step all the time. They changed from shoulder to shoulder without my feeling it…

‘Sometimes I passed or was passed by the camels, which seemed to be winding about over rocks and hills, but I went over these ways too. The last time we passed I thought it very unlike Theodore never to give me a look but stare straight before him, but then I did not know of his miserable condition. There was a delightful sea wind which came over my head, stronger and stronger, and just seemed to keep me alive. They carried me headfirst. I did not think they would be pleased if I constantly asked how far we were off still, so I only said civil things, but right glad was I, at last, after 15 or 16 miles to find myself in the thick of a rushing, roaring rabble rout of men, women and children, not a thing I really like in general but now it told of the end of my weary journey.’ [From ‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Volume lll: Southern Arabia and Persia’, page 322. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2010]

PPS: However, could this also be a photo of Mabel, perhaps, taken at around the same time at Karnak on the banks of the Nile? Thanks again to Anna Cook, we have a possible image of her from Moses Cotsworth’s pamphlet ‘The Fixed Yearal’ (available online from archive.com), which was probably published around 1914. It shows a woman in travel attire (does the hat match the photo above?), in shade alas, on the right, in front of one of the Karnak pillars. We have no proof that it is her, but Anna Cook, the Cotsworth specialist pins a note to it: “But he [Cotsworth] only travelled to Egypt around November/December 1900 and had his camera stolen so I suspect that the photos were given to him by Professor Wright – his travelling companion. I know that Wright was a widower who travelled with his son and that Cotsworth’s wife was at home in England so really Mabel is the only woman that was around in the right place at the right time and we know that she did travel with Wright and Cotsworth for a time.” (Anna Cook, pers. com., 01/2019)

We do have an earlier Karnak extract from Mabel’s diary: “[Monday] January 31st [1898]. When I reached Luxor I was asked to join a party consisting of Mr. and Mrs. Edmund Sebag-Montefiore, Mr. and Mrs. W. Wilson (who were travelling together) and Mrs. and Miss Wibbs [?], one a doctor, and have a special dragoman, Abdul el Kawab, a very good man. We went in the only two carriages to see Karnak by moonlight, a truly awe inspiring sight. [Tuesday] February 1st [1898]. We went again by the light of the sun and came back to luncheon.” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent, Vol 2, The African Journeys’, page 270, Archaeopress 2012)

However this is a year before Cotsworth went to Karnak to take his calendar readings; Mabel, recently widowed, was on Nile cruise run by Thomas Cook and did not proceed to Jerusalem that year – she was lonely and cut short her tour, returning to London via Athens (she headed her diary ‘A lonely useless journey). But let’s make a case for her meeting Cotsworth, feeling less lonely, in the winter of 1899/1900 and deciding to join his party for another Nile cruise and then onwards to the Palestinian wilds (where she broke her leg! See above).

PS: An update from Anna Cook (March 2021): ‘Not sure if I’ve mentioned it before but I came across a reference to Theodore in Cotsworth’s The Rational Almanac – page 392. “Mr. R. N. Hall, writing in the Sphere, page 238, for June 13th, 1903, states that he there [Zimbabwe] found a Solar Disc (made from Soapstone) carved with a circle surrounded by 8 smaller circles or knobs, similar to the markings on the ornate object previously found at Zimbabwe and pronounced by Mr Bent to be a ‘sun-image’.” Another mention occurs on page 419 “That late esteemed explorer Mr. Theodore Bent, made the preliminary survey of the more conspicuous remains described in his classical work The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, pointing with Mauch to the Semitic peoples as the exploiters of those rich Goldfields.”‘