In the late 1920s, Mabel Bent’s niece, Violet Ethel ffolliott (1882-1932) transferred the care of her elderly aunt’s travel diaries, as well as some notebooks of her husband’s, Theodore Bent (1852-1897), archaeologist-explorer, to the Hellenic Society in London.

Both Theodore and Mabel had been associated with the Society since the 1880s. The institution had started in 1879, and by 1883 Theodore was a member, indicating his growing interest in archaeology (he read history at Oxford). In 1885 he joined its Council and remained on it until the year of his death (1897). Women members were welcomed and contributed greatly; Mabel became a member in 1885. The Society held three or four meetings a seasons, including a General Meeting in London in the summer (at 22 Albemarle Street). The Bents were rarely in the country in time for the winter and spring meetings but, apart from 1891, when they were in Africa, they would have attended the AGMs. The Society’s journal, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, is available online (with the early years as open access), and from 1883 to 1918 one will find references to either Mr or Mrs Theodore Bent within its pages.

However, this institution, having to do, broadly, with things Greek, might at first glance appear an odd choice as a long-term home for these memoirs of travel and exploration associated with remote corners far away from the Eastern Mediterranean; only about half the couple’s twenty years of adventures were primarily dedicated to Greece and Turkey, the other portion, more often than not, found them dusty and deep in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

And after all, Theodore was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, whose orbit was the whole world, and the latter often funded and supported Bent’s expeditions; in return, he wrote and lectured for them constantly until his early death. So why not leave the Bent notebook collection to the RGS Mabel? A possible answer might be linked to the infamous scandal involving women RGS Fellows in the early 1890s. Mabel was on the list for the second allocation of Fellowships to noteworthy women travellers just at the time the RGS Committee voted against the idea, and women were not readmitted until some twenty years later. Proud Mrs Theodore Bent might well have remembered this obvious slight and opted to lodge her travelogues in the archives of the sociable and patrician Hellenic Society instead.

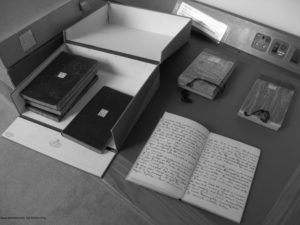

Whatever the reason, the Bent Collection has remained in three stout boxes in a secure library room in Senate House, London, ever since, available for private research on request (although Mabel’s ‘Chronicles’, as she called them, have since been transcribed and published by Archaeopress, Oxford, in three volumes).

However, advances in scanning techniques, and associated software, not to mention generous support, very appropriately, from the AG Leventis Foundation in this case, now mean that the Bent notebooks can be reproduced digitally, facsimile, ink blots, doodles and all, without risk to the original delicate material.

To quote the specialist involved: “For the vast majority of the time I am using a Bookeye 4 Kiosk book scanner to capture the image data and BCS-2 imaging software to process and format the images once they have been transferred from the scanner… When digitising a volume each page is saved and formatted as a single 600DPI TIFF file, all these files are then collated and converted into a single, readable book format PDF.”

And, most importantly of all, they are available, open-access free, to anyone, anywhere in the world, with an interest in 19th-century travel into those regions that attracted Theodore and Mabel Bent – from Aksum to Zimbabwe.

Accordingly, these notebooks have now been scanned and a digital catalogue produced. All Theodore’s notebooks in the archive have been finished, and all Mabel’s too – n.b. her 1896/7 volume covering Sokotra and Aden, the setting for the couple’s final journey together, was scanned last and is available here. (It should be noted here too that the diaries covering the Bents’ expedition to Ethiopia in 1893 were apparently never given to the Hellenic Society for some reason, and, for now, assumed lost – always the hardest word for a traveller to utter.)

Society, London).

So, what follows will take you to some very faraway places indeed – you only have to click to be transported (our pages and maps on the Bents’ explorations provide useful background information):

Greece and the Levantine Littoral

Mabel Bent (1883/4): The Greek Cyclades

Mabel Bent (1885): The Greek Dodecanese

Licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Theodore Bent (1888): Inscriptions from Patara, Lydae, Lissa, Myra, Kasarea, Nicaea, etc.

Bahrain and Iran

Africa and Egypt

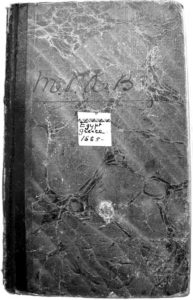

Mabel Bent (1884/5): Egypt (before steaming to the Greek Dodecanese)

Mabel Bent (1890/1): South Africa and the expedition to Great Zimbabwe (I)

Mabel Bent (1890/1): South Africa and the expedition to Great Zimbabwe (II)

Mabel Bent (1895/6): Sudan and the western Red Sea littoral

Theodore Bent (1895/6): Sudan and the western Red Sea littoral

Mabel Bent (1897/8): Alone in Egypt (‘A lonely, useless journey’)

Southern Arabia

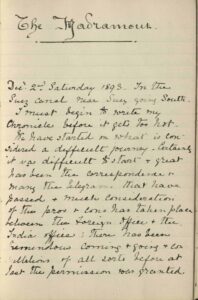

Mabel Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (I)

Mabel Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (II)

Theodore Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (I)

Theodore Bent (1893/4): Wadi Hadramaut (first attempt, via Mukalla) (II)

Mabel Bent (1896/7): Sokotra and Aden (this volume has not yet been scanned [Feb 2022])

Theodore Bent (1896/7): Sokotra

Theodore Bent (1896/7): Sokotran glossary and notes (Bent’s final notebooks)(I)

Theodore Bent (1897): East of Aden (Bent’s final notebooks)(II)

Coda

Mabel Bent died at her London townhouse, 13 Great Cumberland Place, on 5 July 1929 at the age of 82. Her Times obituary (6 July 1929) includes that, “as an experienced photographer and accurate observer, she was of enormous assistance to her husband and famous for the explorations in distant lands which she undertook with [him]. This was at a time when it was much more rare than it is now for a woman to venture forth on such journeys […] During her long widowhood [Theodore died a few weeks after scribbling in his final notebook above, in May 1897] of more than 30 years, Mrs. Bent was well known in literary and scientific London. She was a good talker, with an occasional sharpness of phrase which was much relished by her many friends.”

And would there be any ‘sharpness of phrase’ about seeing her ‘Chronicles’ now scanned and widely available? Did Mabel intend them for publication? Apart from the fact that Theodore relied on his wife’s notebooks for the provision of background details in his monographs, articles and lectures, the chronicler has left one or two clues within her pages.

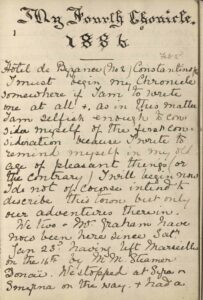

From ‘Room 2’ of the Hôtel de Byzance, Constantinople, in February 1886, Mabel confides, in one of her happiest diaries it seems: “I must begin my Chronicle somewhere if I am to write one at all and as in this matter I am selfish enough to consider myself of the first consideration because I write to remind myself in my old age of pleasant things (or the contrary) I will begin now.” Thus we know, at least, that they were for her to read later in life, and that she intended her aunts, sisters, and nieces to share her adventures. (There are several asides such as, “We have constant patients coming to us and I am sure you would all laugh to hear T’s medical lectures.” And “You must excuse these smudges as I am sitting cross-legged on T’s bed.”).

There is also certainly nothing in her millions of words that could be considered as indiscreet, let alone anything close to libel – or nuptial intimacy for that matter – although there is a little false modesty and coquetry here and there. (Only two or three pages have been removed from the entire series of notebooks.) What is omitted, invisible, becomes visible and striking, however. In all her diaries there is not one reference to the losses of her childhood – her poor mother, her difficult father, and her two dead brothers.

But the most obvious hint that Mabel, at the very least, might be aware of a potential wider interest in her ‘Chronicles’ is the letter still preserved (in the 1885 volume) from her friend, Harry Graham, who shared in some of their travel that year, complimenting her thus: “I carried off your Chronicle… and… I never enjoyed these hours more than when reading it in the train coming down here yesterday – as soon as I have finished it I will send it you back – but why oh why don’t you publish it? It simply bristles with epigrams and I am certain would be a great success! You ought to blend the 2 Chronicles into one and I am sure everyone would buy it.”

Well. Perhaps not everyone. Mabel’s Chronicles are not great travel literature. They are her on-the-spot recollections of long days spent trekking, exploring, digging, dealing with villagers, arguing with minor officials; they are snatches of gossip, snobbishness, likes and dislikes, barking dogs, vicissitudes, poverty and pain; they are delightful souvenirs of music, dancing, colourful costumes and wonderful meals.

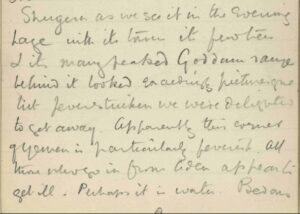

And how few are the references to limb and life. Just hours from complete malarial collapse, east of Aden, in the alarmingly named heights of ‘Goddam’, Theodore scribbles, in his final notebook, only weeks from his death at 45, “… but feverstricken we were delighted to get away. Apparently this corner of Yemen is particularly feverish. All those who go in from Aden appear to be ill. Perhaps it is [the] water…”

There are certainly passages that reflect her times, too, and which are inappropriate today. Great travel literature? Clearly not. But great travel writing – accounts of wonderful endurance and reflections of courage, attitude, apogee of empire, and spirit – most certainly.

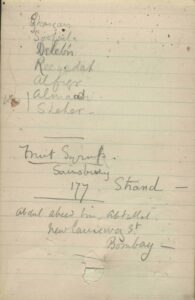

It’s also nice to know the couple apparently liked their fruit syrup from J. Sainsbury!

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article