Harare being in the news (November 2017), here is Mabel’s sketchy account of their brief sojourn there in September 1891. Mabel and Theodore were at the ‘Nwanetsi’ river on 18 May 1891 and were soon camped by the Umfuli, some 40km due south of ‘Fort Salisbury’. Cecil Rhodes’s exploring ‘Pioneers’ (see later) had decided to halt their expedition between the kopye, called by the Mashonas ‘Harari’, and the river Makubisi, and to build their base there. The fort took its name from Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903), then Prime Minister. Later, F. C. Selous recorded: ‘It is a matter of history that on the 11th of September 1890 the British flag was hoisted at Fort Salisbury, on the banks of the Makubisi river, and the expedition to Mashunaland thus satisfactorily brought to an end.’ The modern historian Tawse Jolie elaborates: ‘A full-dress parade was called at 10 a.m., 13th September, 1890, the seven-pounder gun fired a Royal Salute, Canon Balfour said a prayer, and the British Flag, the Union Jack, was hoisted by Lieut. Tyndale-Biscoe of the Pioneer Column.’ The site of course is now the modern capital of Zimbabwe – Harare.

Let’s hear from Mabel:

‘Tuesday, September 8th [1891]. We reached Fort Salisbury about 8 o’clock a.m. A man was sent on, riding, to enquire where we were to stop, for we hoped to be spared from the public outspan. We thought we should never arrive. We were half dressed and I was wrapped in a cloak. We drove all through the trading part, which is very extensive and consists of round huts, a few square houses being built, wagons and tents of all sorts, and booths and bowers grouped round a long, low, wooded hill. Then through the camp and past the fort and on to the civilian part and Dr. Harris said we were to outspan in that neighbourhood – the hospital and nuns’ dwellings being beyond. Before we had stopped, we were greeted by Dr. Harris and Captain Nesbitt and we and Mr. Swan were invited to take our meals at their mess during our stay. This invitation is of great monetary benefit to us, besides we could not get the food even if we did pay for it. Provisions are frightfully dear and scarce. Sugar 3/- a lb, milk 5/6 a tin, jam 4/6 a lb, ham 4/6 a lb, and everything is in proportion. A pair of common hinges 7/-, 1⁄4 lb of tin tacks 11/6, and 1 lb of paint 35/-. As for meat, it is very hard to get, and a worn out ox just crawled up in a wagon is really so tough that one can’t get ones teeth through it, and those we left in our camp got none…

‘After breakfast we began in real earnest sorting our baggage; some for England via Cape Town; 2 to go down the Busi with us and be sent by B.S.A. wagons to Umtali’s to meet us; 3 to go to Matoko’s; 4 to be sold; 5 to take to the Mazoe River. The bucksail was made into a tent for packing, but we were very much impeded and had two give up at times on account of the ferocious wind which raged all the time of our stay and brought layers of dirt into the baggage. All our white men sought places and all found them. Mr. King is to open a store for the Co. at the Mazoe River. We stayed till Tuesday morning. We saw a great many friends. Two days I had tea with the nuns who also came several times to see us. Mr. Stokes also, and an old friend of Mr. Swan’s, Mr. Macfarlane. Mr. Swan and I had tea in both these huts. Major Browne had walked in the last 30 miles and we had visits in our tent all day. One night (Thursday) [10 September 1891] we dined at the officers’ mess. They had made the dinner table so pretty with Mr. Coope’s puggaree, yellow silk, and ostrich feathers. The fatted calf had died and was served up in 6 quite different ways: cutlets, tongue, roast, pie, and 2 others. In the dining room is a hat rack – 6 rhinoceros horns…

‘Constable, our cook at Zimbabwe, was engaged by Dr. Harris for the civilian mess. He is abominable to us. Instead of coming forward like an honest man and counting on out our enamelled iron and kitchen things, we have to wring them out of him cup by cup. When we ask for things he says they are gone to the auctioneer but the list shows the contrary. The last day he kept out of the way and on Tuesday morning, though we were up at dawn, he had already cleared out. I suppose when we get back tomorrow evening that there will be a row. The auction is for Saturday. Besides our own affairs, there has been on last Saturday the First Annual Dinner on Occupation Day. Theodore was invited. The Pioneers hate Dr. Harris and Major Tye. The Chairman, Mr. Bird, made the rudest of speeches, which Dr. Harris ably responded to and most pluckily. The Pioneers had many grievances but some must have been trivial indeed. One of them was that a notice was put up at Zimbabwe forbidding anyone to remove antiquities. No such notice was put up, yet more than once it was complained of and one man said he had seen it. They managed to make Dr. Harris tell a lie for the pleasure of confounding him. When he said he had had official news from Cape Town that Mr. Rhodes was coming to Tuli, they told him it was a lie for he was coming by the Pungwe, they having concealed the news from Tuesday to Saturday on purpose…

‘Saturday 19th [September, 1891]. Our sale took place this morning but we do not know the result quite yet. Some of the things seem to have gone high enough: whisky £2 a bottle and brandy £3. We afterwards were quite satisfied. Some people certainly got good bargains, but then so did we: A [quart] of spirits of wine £1.10; 1 doz. 1⁄2 [bottles] champagne £1.5….’

Rhodes’s marshals

The much put-upon ‘Dr Harris’ is Rhodes’s local top man, Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris (1856-1920). Qualifying in Edinburgh he had moved to Kimberley ten years before Mabel meets him. His rise in Rhodes’s service was rapid. He has been described as a ‘coarse, ambitious adventurer…[who] came to be regarded as a loudmouthed braggart and born intriguer whose penchant for mischief-making caused Rhodes endless trouble.’ He is back in England by 1905, where he was ‘associated with some few finance Cos…and entered the arena of British politics in 1900 as Conservative M.P. for the Monmouth Burghs…Dr. Harris is a keen dog fancier, and is very popular in South Wales, where he spends most of his time.’ (1905)

Much conspicuous by his absence from Mabel’s pages is Dr Leander Starr Jameson (1853-1917). His exploits for Rhodes, his patron, are legion, none more so than the infamous ‘Raid’ of December 1895, and he was by Rhodes’s side when he died in 1902. By September 1891 Rhodes had appointed him as his deputy in Mashonaland and he arrived a few days after the Bents had left Fort Salisbury. Rhodes himself and his party arrived at the mouth of the Pungwe on 26 September 1891, and headed west to Fort Salisbury as Theodore and Mabel were about to move east – they missed crossing paths when the Bents made their detour north. Earlier, however, they did encounter another of Rhodes’s great marshals and later philanthropist, Alfred Beit (1853-1906). Born in Hamburg to a well-to-do family, he arrived in Kimberley in 1875 to deal in diamonds and within a few years had become Rhodes’s colleague and ally and one of the four principal founders of De Beers. Diamonds and gold provided the capital on which Rhodes’s associates thrived, but the Barberton fields in the eastern Transvaal (as mentioned by Mabel) promised much but delivered little. Beit died soon after Rhodes and left his fortune as the Beit Trust which focused on educational projects in Zimbabwe.

A little more in the way of background

Under the concession negotiated by Charles Rudd (13 October 1888) for rights from Chief Lobengula to develop the territory of ‘Mashonaland’, Cecil Rhodes, via his British South Africa Company, quickly assembled in 1890 a small armed force (‘The Pioneer Column’) to annex the lands. The force assembled in May on one of Rhodes’s farms outside Kimberley and by 28 June they were at Macloutsie camp. Headed overall by Col. E. G. Pennefather and Sir John Willoughby the troopers mainly comprised well-connected young adventurers, given promises of grants of land by Rhodes. The contingent crossed the Tuli River and headed roughly north, over 600km of difficult terrain, towards Mount Hampden. Here they established a base (12 September 1890) that became known as Fort Salisbury, then Salisbury, and now Harare, capital of modern Zimbabwe.

Rhodes, the great puppet master, had plans for Theodore, too, with his agents working behind the scenes to persuade him and Mabel to explore/excavate the monument known as ‘Great Zimbabwe’ and have it written up as being ‘Phoenician’ (or at least non-African) in origin. After exploring the Great Zimbabwe ruins in the summer of 1891, Theodore’s party made its way north to Fort Salisbury, before detouring to explore some gold workings, deliver tribute to a nearby chief, and then descend, via the Pungwe valley, to the sea at Beira for their voyage home to England, via Lisbon.

Mabel was seeing the ‘capital’ of course in its very early months. Jan Morris provides a snapshot: ‘Until 1891 it had been a bachelor community and half its citizens indulged in African mistresses. Since then many white women had arrived, and the town had acquired a streaky veneer of decorum…The social centre of the colony was Government House, a pleasant rambling bungalow in the Indian manner…There were Fred Selous…Mother Patrick, the saintly young superior of the Dominican Sisters…Major ‘Maori’ Browne…ill-explained aristocrats like Lord George Deerhurst, who ran a butcher’s shop on Pioneer Street, or the Vicomte de la Panouse, popularly known as the Count…’ Theodore and Mabel encounter most of these characters at one time or another on their year-long adventure.

Before the Pungwe (late October 1891) and the journey home, the Bents enjoy a few days’ rest at Umtali with the companionship of a trio of celebrity British nurses recently arrived there (also courtesy of Rhodes’s benevolence) – Rosanna Blennerhassett, Lucy Sleeman, and Beryl Welby. Two of the three compile later a popular account of their adventures; they recall the Bents’ brief sojourn and Theodore’s latest thoughts on the monuments: ‘He was fresh from those strange Mashonaland ruins which have given rise to so much conjecture. Mr. Bent supposed them to be extremely ancient. He told us that, without consulting the archives at Lisbon, he could not give a decided opinion on their origin. At that time he seemed to believe them to be the ruins of a temple and fortress. There, he thought, weird rights had been solemnised and fierce battles fought… Mr. Selous differed entirely from this view. He believes the ruins to be comparatively modern, and the remains of native work… [He] is probably the best authority on the subject, knowing Africa as thoroughly as he does, and being able to converse with the native as easily as with an Englishman, whilst Mr. Bent could neither speak nor understand the language. But Mr. Bent appeared certain that the Portuguese only could throw light on the problem. He said that the Portuguese had certainly been all over the country, and that a Portuguese archaeologist who would devote himself to the subject would find the archives, of Lisbon, and very likely of other old cities, rich in most interesting materials.’

It is easy to see the nurses preferring Selous to Theodore. Frederick Courtenay Selous (1851-1917) fits this casual aside here as a rhinoceros might a garden shed: RGS Founder’s-medal-winner (1893), big game hunter, trail blazer, road builder, cartographer, diplomat, emissary, naturalist, writer. Legend has it that he was the one to break the news to Rhodes of the death, by an explosion of alcohol, of his brother Herbert. Born in 1851, Selous – ‘well over medium height, with fair pointed beard and massive thighs and legs, it was his fine blue eyes, which were extraordinarily clear and limpid, that most attracted attention.’ – first began to haunt Mashonaland when he was twenty. His subsequent reputation brought him to Rhodes’s attention and after having been involved in the ‘negotiations’ to acquire Mashona territories, he was recruited (and well incentivized) to guide the Pioneers to a site near modern Harare (Fort Salisbury), which was to become Rhodesia’s capital – a site that Selous himself had singled out from his previous explorations in the area. Press reports did not exaggerate when they wrote that Selous had ‘done more than any other man to bring Mashonaland into notice, and is credited, together with Cecil Rhodes, with having contributed most to the creation of Rhodesia’. Of his exploits, Selous himself opined that: ‘Such undertakings as the expedition to and occupation of Mashonaland cannot but foster the love of adventure and enterprise, and tend to keep our national spirit young and vigorous’, and that the ‘opening up of Mashunaland seems like a dream, and I have played a not unimportant in it all, I am pleased to say. The road to Mashunaland is now being called the ‘Selous Road,’ and I hope the name will endure, though I don’t suppose it will.’ Selous did very well out of Rhodes, who rewarded him with a large cash payment, 8,500 prime Mashonaland hectares, and 100 De Beers shares. By June 1892 the adventurer can write to his mother that ‘I can live on the £330 a year which my de Beers shares produce.’ By 1900, surprisingly, he had retired to a fine home in semi-rural England (Worplesdon, Surrey), but with the coming of the First World War, at the age of sixty-four, he joined the ‘Legion of Frontiersmen’ as captain and left to serve in East Africa. The big game hunter fell himself to a German sniper’s bullet to the head on 4 January 1917 on the edge of the Rufiji River. His grave is close by, in the Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania, topped with stone and brass. There would be no Mashonaland routes taken by Theodore and Mabel that were unknown to F. C. Selous. His beautifully bound books, in their original editions, were extremely popular in his day. (A rumour he did little to refute was that he was the model for Haggard’s Alan Quartermain; Theodore being another, by the way.)

Selous, it seems, avoided the Bents that September in camp Salisbury. As ever, he had things to do. Such was the food crisis (alluded to by Mabel in her diary) that Selous was given the task of guiding in the relief column in. One morning Theodore (as he relates in his great book ‘The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland’, page 283) espies the legendary figure ‘hurriedly dispatched to bring up the waggons at any cost. A few weeks later we heard that they had arrived, and the danger which had threatened the infant Fort Salisbury was averted’.

PS: Mabel writes home to Co. Wexford from Harare, September 1891

…and, by chance, we have a letter home to Co. Wexford, from Mabel. It is headed ‘Umfouli R[iver], September 5th 1891, finished 9th [September] at Fort Salisbury’

My dearest Faneen & L[oodleloo], Iva & E[thel]

I was in the midst of a letter but implored the cart to wait while I shut it up as I knew it was long since you had news. I wonder if you saw the telegram I sent from Fort Victoria in answer to one to report progress.

Well I will go on where I left off. We dined sitting on our bedding and soon went to bed, pretty tired. The days very hot and the nights sometimes dreadfully cold. It is rather hard on one not having some servant but we had no means of getting one. We meant to take a B.S.A.[C.] man as interpreter, but he was ill and we waited 2 days then took our head man, Meredith, who can talk Zulu, and one of our 9 [local men] could understand him, so we got on very well. We can say a few things now ourselves; so the wagons were in command of Alfred, no. 1 driver. Constable, cook, a black, leader [and] no. 2 driver of our wagon, and O’Leary, a man who is having a passage given; he feeding himself (not really though). He has been with us since May, digging at Z[imbabwe].

Since Fort V[ictoria], where a leader and driver left, we have been short of a leader and hoped to get one from Major Browne, who would have been glad to save his food and pay, as he has lost so many oxen, but he is so much behind and we can’t [wait?], so we get on without. A leader is the lowest. He puts on the break [sic], drags the oxen into the right path, for they have no other guide, and takes it in turns with the other leader to go and herd the oxen when grazing. 2 naked [local men], or rather with 2 little skin aprons apiece, drive the donkeys and horses.

We shall be so sorry to have to sell the latter at Fort Salisbury. No one can catch them so well as I, particularly mine, which races away, but they always come to get bread. We have been to some new large unknown ruins, Matindela, and discovered others of which we could find no name. We must sell the horses if we go down the P[ungwe River], because one bite of the tsetse fly would kill them at once and we shall get at least £350 for them. The donkeys do not die till the beginning of the rainy season.

We hear dreadful accounts of how the porters forsake you in the worst place if you do not comply with exorbitant demands. But we have 7 donkeys. It is about 400 miles. At Fort S[alisbury] we shall sell the wagons for little and the oxen for much and divide our clothes, sell some and carry what is absolutely necessary for the steamer from Beira to the Cape, and buy there, for the clothes, etc., we send down won’t be there in time to meet us.

September 8th [1891] We arrived this morning sending a rider on to ask where we were to outspan, for we are very privileged persons, so we are quite away from the public outspan, which is like a dirty farmyard and between the military and civilian quarters. We arrived neatly dressed and were met by invitations to luncheon and breakfast. Very nice not to have to wait till ours was unpacked. There is very little food here: jam 3/6 a pot, and milk – but you can’t buy it – 4/6; ham 4/6 a lb. We have more ruins to see, but our plans are not made till this afternoon. The camp is on half rations.

We have now settled to go down the Busi, and the latter part, each in our own canoe. We are going first to Matoko’s, then to Makori’s; and to Matoko’s we are to be the bearers of the £40 of presents annually given, so are sure of a very good reception. We are to take a trooper with us and Meredith and Alfred, a driver, as personal cook, a very nice fellow, 10 donkeys and 2 of the Makalankas we have had for more than a month, besides other carriers.

We are invited to take all our meals at the mess – a very substantial money saving now. If it weren’t that we are permitted to draw rations we could not get enough food – no milk or meat. So now our men have a good opportunity of seeing that ‘Wilful waste makes woeful want’.

Dr. Harris, who is head here now, is much pleased with Mr. Swan’s beautifully made maps. Well you see that we are doing well, but alas! When the oxen came in this evening one has lung sickness, so we don’t mean to let that be known and hope to sell the others tomorrow. At the mouth of the Busi we shall go down to the Cape to see the library there and call in Lisbon on the way and hope to be home the beginning of December.

There are no ladies here, but one or two traders’ wives and the nuns. How wonderful it is how the Jesuits get in everywhere…

The rest of the letter is missing, but Mabel used to sign off as ‘Your most loving Mabel’, so let’s do that here.

Notes

The ‘Mr. Swan’ referred to is the Bents’ particular friend Robert McNair Wilson Swan (1858-1904). The Swan brothers were mining emery in the Cyclades in 1883/4 when the Bents met them. He contributed an odd section in Bent’s Zimbabwe monograph on the subject of measurements and other data relating to the ruins, and not much taken into account today. He died, a rather sad figure it seems, in the Far East.

(Swan, Robert McNair Wilson, 1858-1904)

Sister: Ethel Constance Mary Bagenal (née Hall-Dare, d. 1930). She had married Lieutenant Beauchamp Frederick Bagenal in 1870 and the couple had 5 children. Their family residences at Bagenalstown and Benekerry (Co. Carlow) were very close to the Hall-Dares at Newtonbarry (now Bunclody) (Co. Wexford).

Sister: Olivia (Iva) Frances Grafton Johnston (née Hall-Dare, d. 1926) lived in Bournemouth (Theydon Lodge, Boscombe) on the south coast of England. Called Iva by her family she was the third wife of the Reverend Richard Johnston (1816-1906) from Kilmore, Co. Armagh (d. 1906). They married in 1883 when he was nearly 70 and Olivia was about 40. The couple moved later to Bath after Richard’s retirement from his Kilmore parish church.

Sister: Frances Maria Hobson (née Hall-Dare), known to one and all as Faneen (b. 1852) married the Reverend Edward Waller Hobson (b. 1851) on 11 June 1891. (He played rugby for Ireland in his youth and went on to have a successful career in the Church of Ireland.) During the writing of this letter the couple were based at Moy, Co. Tyrone (1881-1895); the rectory of St James’ all but abuts the church. All Mabel’s letters were meant for circulation among her sisters and other relatives.

Aunt: Olivia Frances Lambart (‘Loodleloo’), sister of Mabel’s mother, Frances Anne Catharine Hall-Dare (née Lambart, d. 1862). A spinster, Loodleloo was in effect the children’s guardian following the death of both their parents (their father Robert Westley Hall-Dare (b. 1817) having died in April 1866). She died on 9 July 1898, a heavy blow for Mabel (and her sisters), just fourteen months after the death of Theodore in May 1897.

For details of Mabel’s family, see Hall-Dare at http://www.thepeerage.com/i1692.htm#s22714

For more on Mabel’s letters, see http://tambent.com/mabels-letters/ and the collection in the Royal Geographical Society, London (https://rgs.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=330)

All Mabel’s quotes are from ‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent. Volume II: The African Journeys‘ (2012, Archaeopress, Oxford).

For any other reference or explanation, please contact info@tambent.com

The images are:

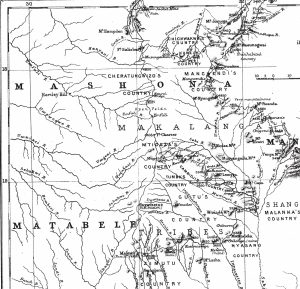

1) Detail of Map: ‘Part of Matabele, Mashona and Manica Land, illustrating the journey of Theodore Bent, Esq. from Shoshong to the Pungwe River.’ (Fort Salisbury (Harare) is roughly at Lat. 18/Long. 31) From ‘Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society’, Vol. 14, No. 5 (May 1892), facing page 298. Private collection.

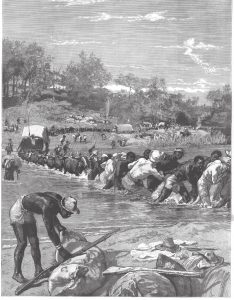

2) ‘Crossing a stream. The Pioneer Corps of the British South Africa Company on the way to Mashonaland’. Cover illustration (detail) from The Graphic, 25 October 1890. Private collection.

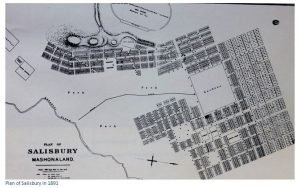

3) A plan of Fort Salisbury as Mabel and Theodore would very likely have encountered it in September 1891.