Lindos: The Living City of Homer I – with pictures by Sir Frederic Leighton, P.R.A., by Theodore Bent (1891)

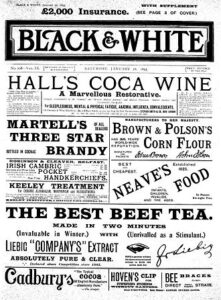

[A little-known article, not available elsewhere digitally we believe, by Theodore Bent published in Black & White, 28 February 1891, pp. 109-10. (For some background, see after Bent’s text.)]

“The illustrations before us are reproduced from studies made by Sir F. Leighton at Lindos, one of the most ancient of all Hellenic towns, the foundations of which carry us back far into those mystic ages, when early Egyptian enterprise first reached the soil of Hellas. Three mythical brothers, Ialysos, Camiros, and Lindos, divided between them the Island of Rhodes, the first halting place reached after crossing the open sea; they built three towns and called them after their own names, and long before the capital of the island came into existence, Lindos was there, carrying on her trade with Egypt. Of these three coëval towns, mentioned by Homer in one line, Lindos alone survives, thanks to its harbour and its prominent position on the eastern coast.

“As you descend the steep olive-clad hills behind Lindos on muleback, the city lies at your feet spread out as on a map. A narrow promontory there breaks into several small bays, two of which form the harbours, and the city lies between them; just the very site that those early navigators looked for, so that whichever way the wind might blow ingress and egress from one of the ports could be effected. A similar instance occurs at the town of Cnidos on the opposite coast, at the end of the Doric Chersonese, and at many a ruined site on the Ægean shores like harbours can still be seen.

“The harbour, to the north, is spacious; but despite the protection of some small islets it is very dangerous when the S.E. wind blows. Beneath the waves on a calm day, with the aid of a tin cylinder with a glass bottom – an instrument used by the fishermen of today in searching for the haunts of the sponge or the octopus – you may see the foundations of an ancient breakwater long since ruined. The harbour to the south is well sheltered by high rocks; but it is very shallow now, and only available for small craft. At the extremity of the peninsula, on an abrupt rock rising some 600 feet from the sea, now stand the massive battlements of the castle constructed on the site of the ancient Hellenic acropolis by the Knights of St. John, who, during their tenure of the island of Rhodes, held Lindos as second only to the capital in strategic importance.

“The road descends rapidly as the town is approached. It is flanked on either side by tombs of departed Greeks, rifled and overthrown centuries ago. The flat-roofed, whitewashed houses of the fishermen are tightly wedged together in the narrow valley. Most of these consist only of one large room of uniform arrangement. The family sleep on a raised wooden däis, on which at night time they unroll their mattresses. Painted trunks, spread with Oriental carpets, contain all their worldly goods. Chairs are unnecessary, for they sit cross-legged on the floor and take their meals off a circular board raised half-a-foot from the ground. A great feature of the Rhodian household is the innumerable plates hung for ornament on the walls. Twenty years ago these plates were all of the famed Rhodian pottery, but they have now mostly found their way to European bric-a-brac collectors, and willow-pattern plates and coarse French pottery supply their place.

“Lindos is the reputed home of the Rhodian ware, though direct proof is wanting. One thing is certain, that nine-tenths of the specimens extant come from here, and at the neighbouring village of Archangelos potteries are still to be found. The legend of the exiled Persian potters who worked here in the days of the knights may possibly be true.

“The walls of the peasants’ houses at Lindos, are decidedly decorative, especially if they chance to have the old groined and mullion windows dating from the days of the knights, many of which buildings are still left. On festival days home-made embroideries are hung up from strings, rich in colours, and of elaborate device; the water jars, facsimiles of the amphoræ of bygone ages, contribute to the picturesqueness, and the quaint, much-prized, sacred pictures, with the ever-burning oil lamp before them, shed a holy glamour over the whole.

“In remote island towns, like Lindos, you may still find the women of the old Greek type. In Rhodes, unfortunately, of late years, they have abandoned their quaint, rich-embroidered, costumes; only on such remote islands as Astypalæa and Nisyros can these be found; but the men still adhere to their long, loose baggy trousers, their fez, their embroidered waistcoats and red shoes. On a feast-day as they dance on the flat housetops the old circular dance of the East, which Homer describes, the peasants of Lindos still afford us a living picture of the past.”

J. Theodore Bent.

[Leighton’s pictures, sketches and drawings that featured in the above original article include: – “Lindos Looking North” (page 109); “A Curiosity: A Gothic Archway” (outline sketch) (page 109); “South Harbour” (page 109); “North Harbour” (page 109); “An Interior” (page 110 ); “The True Greek Type of Woman” (page 110). NB: these titles are not necessarily Leighton’s own.]A little background to the above article

Quickly, before taking his wife Mabel to South Africa to explore the ruins of Great Zimbabwe at the end of January 1891, Theodore Bent seems to have been persuaded by a new popular magazine, Black & White, to write two articles about the Rhodian city of Lindos, really to act as wrap-around texts for some paintings, drawings, and sketches of Lindos and Rhodes by Sir Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), the great English artist of his day and President of the Royal Academy.

It has to be said, no information has surfaced so far as to whether Bent and Leighton were friends or why such a piece should have been written, other than it was for the earliest issues of a new magazine (Bent’s piece was published over two editions), and the editors wanted to launch it with the work of ‘personalities’; the magazine was pitched as having a focus on illustrations – to compete with names such as The Graphic and The Illustrated London News.

It has to be said, no information has surfaced so far as to whether Bent and Leighton were friends or why such a piece should have been written, other than it was for the earliest issues of a new magazine (Bent’s piece was published over two editions), and the editors wanted to launch it with the work of ‘personalities’; the magazine was pitched as having a focus on illustrations – to compete with names such as The Graphic and The Illustrated London News.

Sadly, the quality of Leighton’s published paintings in reproduction is poor in these two original Bent pieces and they do not appear here (their titles are listed below Bent’s texts for those interesting in finding them). Replacing them are freely available versions of the popular artist’s works relating to Lindos and Rhodes, and very lovely they are.

Leighton was 37 when called in to Rhodes during a tour of the Levant in 1867. His memories of his stay in Lindos and the area of Neochori (Rhodes Town – non-Turks then could not stay within the walls of the Old Town) stayed fresh with him for the rest of his life, and he used remembered scenes as backdrops in many of his most popular works. Indications of his feelings for Rhodes appear in (1) his letters home and, (2) his diary:

1) Royal Steamer, Adriatic, 28 Nov [1867]: “My Dear Papa… I told you, I believe, in my last how much I had enjoyed and, as I hope, profited by my stay in Rhodes and Lindos… The weather, which was very beautiful at the beginning – indeed during the greater part of my stay in the Island – was not faithful to me to the end; it broke up a few days before my departure, and, to my very great regret, prevented my painting certain studies which I was very anxious to take home: on the other hand, I had opportunities of studying effects of a different nature, so that I can hardly call myself much the loser as far as my work in Rhodes was concerned.”

2) About a year later, on a subsequent trip to Egypt he writes in his diary how a sprig of basil sets him off reminiscing: “As I smell it I am assailed by pleasant memories of Lindos – ‘Lindos the beautiful’ – and Rhodes, and that marvellous blue coast across the seas, that looks as if it could enclose nothing behind its crested rocks but the Gardens of the Hesperides; and I remember those gentle, courteous Greeks of the island… and the little nosegay, a red carnation and a fragrant sprig of basil, with which they always dismiss a guest…”

As for Bent’s text – it’s hack work, cobbled together in an obvious hurry, although his easy, affable style comes through – the same style that was to make his books on Greece (1885), Zimbabwe (1892, and Ethiopia (1893) so popular.

In actual fact, there is a little conceit going on, for although Theodore and Mabel did visit Rhodes in 1885, it was only for a matter of a few days and they never sailed down to Lindos, nor made the lengthy journey there on equids. There are no references in Mabel’s diary to going further than Filerimos, and Theodore would most certainly have written of any Lindian visit in the late 1980s among his many articles on the Eastern Mediterranean. He did publish a review of their days in Rhodes town in 1885, and one or two references in it echo in his two efforts for Black & White. Other echoes sound too – from the pages of such actual visitors (their works surely known to Bent) as Tozer and Newton, and armchair scholars such as Cecil Torr. Bent, in the interests of his own art, was not averse to making things up if needs must…

Click here for Bent’s follow-up article in a later issue, viz “Lindos: The Living City of Homer – II”. Black & White, 14 March, pp. 173-4.

Click here for Bent in Black & White, an Introduction.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article