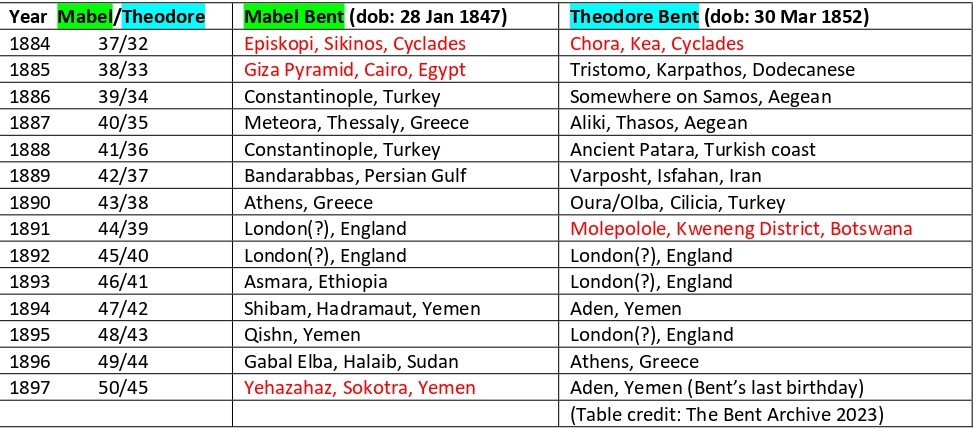

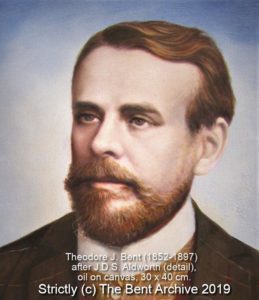

The fifth in Professor Margaret Kenna’s Theodore and Mabel Bent-related series of ‘incidentals’ covering the Cycladic island of Anáfi is all to do with the great monastery site at the western end of the island; that celebrated monument built on the foundations of an ancient temple that perhaps sanctified the locale where Jason and Medea sported – having landed safely in a terrible storm from Crete. But Prof Kenna will fill you in… Margaret is a retired social anthropologist from Swansea University who has been carrying out research on Anáfi, and among Anáfiot migrants in Athens, since 1966. She has written two books and many articles in English about her research: Greek Island Life: Fieldwork on Anafi (2nd edition 2017, Sean Kingston Publishing), and The Social Organisation of Exile: Greek Political Dissidents in the 1930s (2001, Routledge). A Greek translation of the second book was published in 2004 by Alexandreia Press. Many of her articles, in English and in Greek translation, can be found on the websites: academia.edu and ResearchGate. She has also written several booklets which can be found in tourist shops on the island: Anafi: a Brief Guide; Anafi: Island of Exile; The Folklore and Traditions of Anafi, and The Traditional Embroideries of Anafi. She was made an Honorary Citizen of the island in 2006.

This fifth ‘talk’ in Professor Kenna’s thyme-scented series happily coincides with one of Margaret’s regular trips to the island (early June 2018). Go search her out if you are there!

We very much hope you enjoy it and will look out for forthcoming Anáfi ‘talks’ soon on our site; by all means send in your comments to the Bent Archive!

ανάφηανάφηανάφηανάφη

The Bents visit the Lower Monastery/ Temple of Apollo: earlier, and later, visitors

“On January 10th 1884, the Bents went by boat along the south coast of the island with their host, the ‘demarch’ Chalaris, and their guide Matthaios, to the Lower Monastery ‘of Kalamiotissa, on a promontory’, as Mabel writes. She does not mention the huge peak (1476 feet/ 459 metres) of Mount Kalamos above it, although Theodore does: ‘a gigantic mountain rock’ (1885: 50).

Fig. 1: Mount Kalamos, in the distance, at the eastern end of the south coast of Anafi (M. Kenna).

Fig. 1: Mount Kalamos, in the distance, at the eastern end of the south coast of Anafi (M. Kenna).

“A bit of dynamite fishing from rocks along the south coast took place during the boat trip. Mabel writes the initial of the person involved, Theodore tactfully says ‘one of our men’, for then, as now, dynamite fishing is illegal and extremely dangerous. In the 1960s many male villagers had missing fingers or limbs (dynamite was not mentioned to me in the explanations I was given for these injuries), and in the 1980s, two Anafiot men, a father and son, were killed while using it.

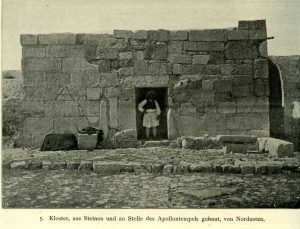

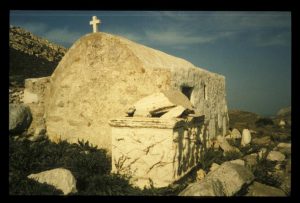

“All that Mabel says of their visit at the monastery is this: ‘The Monastery is a very curious place, built on the site and with the stones, and using much of the old building of a temple of Apollo’ (for the diary references, see Bent, M. 2006: 32-34).

“The church of the Lower Monastery and the monks’ cells are indeed built inside the ruins of an ancient temple of Apollo. The myth is that Jason and the Argonauts were caught in a storm and saved by a flash of light thrown by Apollo, revealing the island to them (one derivation of the island’s name is ‘Revelation’, a parallel to another island sacred to Apollo, Delos, a name which also means ‘to reveal’). Anafi was later a place of pilgrimage to the temple of Apollo, and to other temples built on the site, and became rich enough to have its own coinage.

Fig 2: The Lower Monastery church visible over the wall of Apollo’s temple, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

Fig 2: The Lower Monastery church visible over the wall of Apollo’s temple, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

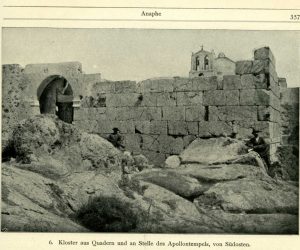

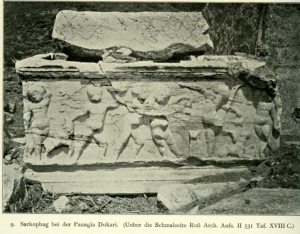

“The Monastery is called ‘Lower’ because there is another very small one, founded in 1715, on the peak of Mount Kalamos. Until 1887 the ikon of the island’s patron saint, Panayia Kalamiotissa (the Virgin of the Reed), was housed in the Upper Monastery chapel, and it was then brought down to the Lower Monastery. The Lower Monastery had been visited by Ludwig Ross in the 1830s (probably on the same visit as the one on which he sketched the sarcophagus described in another blog entry) and a decade later the archaeologist and epigrapher Hiller von Gaertringen would not only visit the Lower Monastery (because of his interest in the temple) but also photograph it, and the Upper Monastery chapel as well. He published the Anafi inscriptions in Inscriptiones Graecae Vol XII, 3: 54-68, numbers 247-319 (referred to here as I.G.). A photocopy can be found in the museum in the village.

Fig. 3: Hiller von Gaertringen’s photo of the Lower Monastery during his visit, c. 1898.

Fig. 3: Hiller von Gaertringen’s photo of the Lower Monastery during his visit, c. 1898.

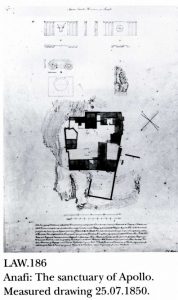

Fig. 4: A ‘measured drawing’ by Laurits Winstrup, Danish architect, of the layout of the temple and monastery buildings. The wall in the photo above is at the top of this drawing (from Margit Bendtsen ‘Sketches and Measurings: Danish Architects in Greece, 1818:1862’. Copenhagen, 1993: 361).

Fig. 4: A ‘measured drawing’ by Laurits Winstrup, Danish architect, of the layout of the temple and monastery buildings. The wall in the photo above is at the top of this drawing (from Margit Bendtsen ‘Sketches and Measurings: Danish Architects in Greece, 1818:1862’. Copenhagen, 1993: 361).

“At the time of the Bents’ visit, the three monks there were mourning the death of their Abbot the previous day (how Chalaris had not heard of this is not mentioned), so the Bents did not stay long. Theodore does however mention that ‘the monastery now belongs to one at Santorin’ (1885: 50). Later events make it clear that another Abbot was appointed, and, indeed, there was one during my own time on the island (when there no monks at the Lower Monastery) who also acted as village priest. It was only after this Abbot’s death in the 1990s that the Lower and Upper Monasteries became ‘holdings’ of the Monastery of Profitis Ilias on Santorini, and renovations were carried out and other changes made.

Fig. 5: The Lower Monastery in 2016. Part of the ancient wall can just be seen bottom left (M. Kenna).

Fig. 5: The Lower Monastery in 2016. Part of the ancient wall can just be seen bottom left (M. Kenna).

Fig. 6: Inside the Lower Monastery, showing the wall of one of the temple buildings, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 6: Inside the Lower Monastery, showing the wall of one of the temple buildings, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 7: The temple building in the photo above, summer 1988 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 7: The temple building in the photo above, summer 1988 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 8: The temple building ‘secured’ by the regional archaeological service (21st Ephorate), 2015 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 8: The temple building ‘secured’ by the regional archaeological service (21st Ephorate), 2015 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 9: Hiller von Gaertringen’s Greek foreman (Angelos Kosmopoulos from the Peloponnese, wearing a fustanella), in the doorway of the remaining temple building, 1898.

Fig. 9: Hiller von Gaertringen’s Greek foreman (Angelos Kosmopoulos from the Peloponnese, wearing a fustanella), in the doorway of the remaining temple building, 1898.

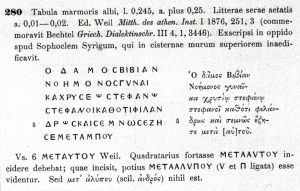

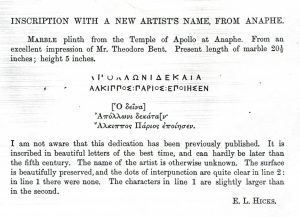

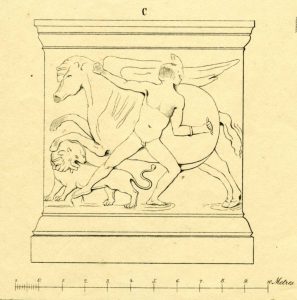

“Theodore refers to Apollo in the god’s manifestation as ‘Aeglites’ (‘radiant’ ‘shining’). However, Apollo on Anafi had an epithet that is unique to that location, which appears in some of inscriptions which Hiller recorded. This epithet is ‘Asgelatas’. Some scholars say this is a variant of ‘aigletes’, radiant, and others relate it to Asclepios/ Aesculapius, god of healing, son of Apollo – so would the epithet mean ‘father of Asclepios’? There are other more controversial interpretations, see ‘Apollo and the Virgin’ in History and Anthropology 2009, available on the websites: academia.edu and ResearchGate. Theodore would surely have known about this epithet as Ludwig Ross had described it (see line 3 of the text in I.G. XII, 248, below).

Fig. 10: One of the inscriptions referring to Apollo as ‘Asgelatas’ (I.G. 248, line 8).

Fig. 10: One of the inscriptions referring to Apollo as ‘Asgelatas’ (I.G. 248, line 8).

“In the summer of 1966, Richard McNeal visited the island and discovered another such inscription, not recorded by Hiller. It is a dedication of an altar and reads, in translation, ‘To Apollo Asgelatas, on behalf of (my) son Aristogenes’. He asked me to take a photograph of it and to make a ‘squeeze’ (papier-maché impression). The Greek word ‘Asgelatas’ is in the third (last) line.

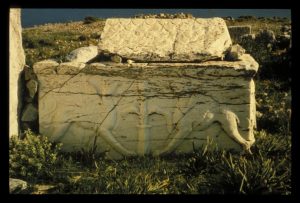

Fig. 11: The ‘Asgelatas’ altar, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

Fig. 11: The ‘Asgelatas’ altar, summer 1966 (M. Kenna).

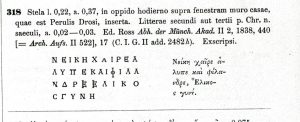

“Another of the inscriptions recorded by Hiller refers to celebrating the rituals of the ‘Asgelaia’

Fig. 12: An inscription recorded by Hiller, mentioning the ‘Asgelaia’. I.G. 249, line 22.

Fig. 12: An inscription recorded by Hiller, mentioning the ‘Asgelaia’. I.G. 249, line 22.

“And what they were, we don’t really know – although they could be an occasion at which men and women traded insults, repeating what is said to have taken place on Anafi when Jason and the Argonauts were insulted by Medea and her women. The women derided the men for only having water (instead of wine or oil) to pour on the sacrificial fire offered to Apollo in thanks for their safe arrival on the island (as reported by Apollonios Rhodios in Argonuatica Book IV, line 1730).

“Theodore notes that at the Lower Monastery, ‘In every direction are to be seen inscriptions let into the walls…. It would appear from the inscriptions that this ground was once covered with temples, the principal one being dedicated to Apollo Aeglites, another to Aphrodite, another to Aesculapius, etc.’ (Bent 1885: 50). His work on the inscriptions appears in another ‘blog’ entry (‘Incidentally II’) .

“Of course, and as ever, far the best thing to do is go see for yourselves! The road there is excellent – you can hire a car, scooter, or bike, but the joy is in the walking – there is a coastal path – and in front of you all the way is the tempting and high Kalamiotissa church in the distance. Go on, you can do it!

References

* Bent, Mabel and Brisch, Gerald (ed.) 2006. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Vol I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral. Oxford, Archaeopress.

* Bent, Theodore 1885 (2002). The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks. Oxford, Archaeopress.

* Ross, Ludwig 1840-1852. Reisen auf den griechischen Inseln des ägäischen Meeres (1840-45). Stuttgart, Tübingen, Cotta [https://archive.org/details/reisenundreiser00rossgoog].

Websites

For the Greek Epigraphical Society, see https://greekepigraphicsociety.org.gr/august-2011/#more-440 (accessed 17/03/2018).

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article