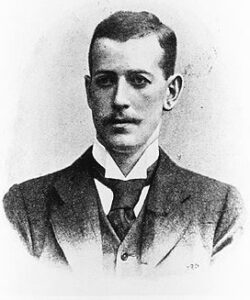

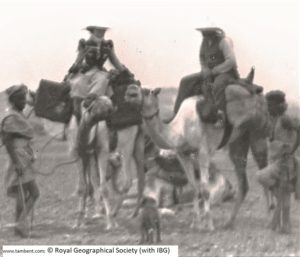

There is no denying that Theodore Bent worked incredibly hard: if not travelling he would be planning the next expedition, fund-raising, researching, writing up, or lecturing. For the approximately twenty years of his travels (coming to style himself more and more as an ‘archaeologist’) he would return to London in the spring of each year (with the odd exception) and immediately begin to think of publishing and publicising his finds – he had always depended much on self-promotion and PR for the funding and support of his subsequent researches; he had good contacts with the press and would submit progress updates to them assiduously from far-flung outposts, via Reuters and other agencies.

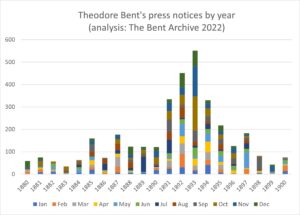

An unscientific trawl through the press cuttings of the time shows how Theodore reached the peak of his ‘fame’ in 1893-4, after a trio of consecutive hits – Great Zimbabwe, Aksum, and Wadi Hadramaut. He and his wife were soon London celebrities and news and details of their adventures was syndicated widely at home and abroad.

An unscientific trawl through the press cuttings of the time shows how Theodore reached the peak of his ‘fame’ in 1893-4, after a trio of consecutive hits – Great Zimbabwe, Aksum, and Wadi Hadramaut. He and his wife were soon London celebrities and news and details of their adventures was syndicated widely at home and abroad.

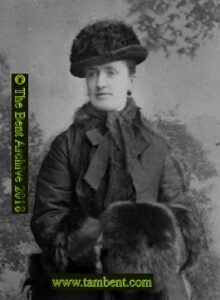

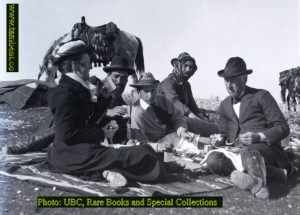

Mabel was tasked with sorting out her photographs and ensuring that they were ready for transferal to lantern-slide or printer’s plate. There was also the constant process of unpacking and caring for case after case of acquisitions: archaeological, ethnographical, botanical, and zoological. The couple would quickly make decisions on what they wanted to keep for themselves, and exhibit in their London townhouse, and what they would offer to museums (for a remuneration if possible).

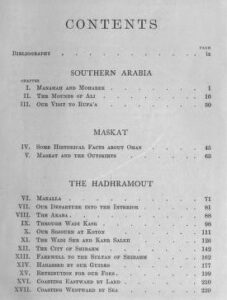

What is particularly striking is how quickly Theodore would settle to study and write up his monographs (frequently asking other specialists for contributions). His hard-pressed publishers (mostly Kegan Paul and Longmans) usually had them announced and on bookshop shelves within six to nine months of Bent’s return from the field.

And within short weeks of reaching home again – from the Levant, Africa, or Arabia – Theodore was ready to give talks and lectures, all over the UK, to the relevant grand institutions of the day, and before the great and the good (in the spring of 1892 even William Gladstone came along to hear). Mabel’s job was to have the lantern-slides ready, and any artifacts neatly labelled for display.

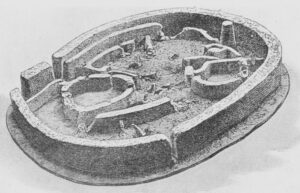

Other display aids might be needed – perhaps a 3D model (e.g. of his famous ‘Elliptical Temple’ at Great Zimbabwe), and then there was the commissioning of maps from the famous London cartographers Edward Stanford to be seen to.

What follows here, taken from newspapers and journals, is a chronological list (with no claims to completeness) of Theodore’s talks and presentations, giving a very good sense of the explorer’s Yorkshire-bred proclivity for hard graft. An interesting additional discovery seems to suggest that there was even an attendance charge for his talks in the provinces! The Newcastle Daily Chronicle for 2 March 1892 records that to hear Theodore lecture in Tyneside would cost you the equivalent of c. £3 today for a seat in the main hall, or c. £1.50 in galleries – money well spent! At another event we hear that Theodore’s ‘remarks throughout were admirably illustrated with a large series of photographic and other views of the places which were visited on the tour. The photographs were the production of Mrs. Bent, and incidentally Mr. Bent mentioned, in apology for some of the views which were somewhat wanting in sharpness, that the technical difficulties of photography, on account of the intense heat and other causes in Arabia, were almost inconceivable.’ (Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, 19 October 1894). Complete sets of Mabel’s lantern-slides survived until the early 1950s, when they were discarded by the Royal Geographical Society, deemed too faded and damaged to merit keeping. A huge loss.

It takes very little imagination today to see Theodore in front of the camera presenting a sequence of his own mini-series – The Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant, The Persian Gulf, Africa North & South, and Southern Arabia. Let’s hope one day they will appear – on National Geographic perhaps!

Theodore Bent’s Talks, Presentations, and Lectures (some dates are approx) note 1

1883 [The Bents make their first visit to Greece and Turkey in the spring]

1884 [The Bents in the Greek Cyclades]

- 8th May: ‘A general meeting of the Hellenic Society will be held at 22, Albermarle Street on Thursday next [8 May], at 5 p.m., when Mr. Theodore Bent will read a paper on a recent journey among the Cyclades.’ [The Athenaeum, No. 2949, May 3, 1884, p. 569]

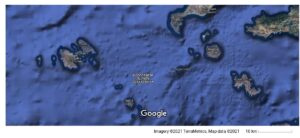

1885 [The Bents in the Greek Dodecanese]

- 14th September: ‘At the meeting of the British Association in Aberdeen… in the Anthropological Section, Mr J. Theodore Bent read a paper to show that the study of tombs in the Greek Islands was conducive to a knowledge of ancient and forgotten lines of commerce.’ [South Wales Daily Telegram, Friday, 18 September 1885]

1886 [The Bents in the Eastern Aegean and Turkey]

- 24th June: At the annual meeting of the Hellenic Society in London the Hon. Sec. read a short paper by Mr. Bent on ‘A recent visit to Samos’.

1887 [The Bents in the Eastern Aegean and Turkey]

- 23rd June: At the annual meeting of the Hellenic Society in London, Mr. Bent gave a short account of his work on Thasos.

1888 [The Bents in the Eastern Aegean and Turkey]

- 11th September: ‘At the meeting of the British Association at Bath… in the Anthropology Section, Mr. J. Theodore Bent contributed a paper on sun-myths in modern Hellas.’ [St. James’s Gazette, 12 September 1888]

1889 [The Bents in Bahrain and Iran]

- 17th September: At the meeting of the British Association at Newcastle, ‘in the Geography Section Mr Theodore Bent read a paper on the Bahrien Islands, in the Persian Gulf, in which he dealt with the position and general features the two islands, character of the seas, and the pearl fisheries and other features.’ [Dundee Advertiser, 20 September 1889]

- 2nd December: ‘The meeting of the Geographical Society on Monday at Burlington House [London] was one of exceptional brilliancy, and was fully attended. Mr J. Theodore Bent… read an interesting and exhaustive paper on the Bahrein Islands in the Persian Gulf. This was rendered the more interesting by some realistic photographs, thrown on a white screen as dissolving views, and taken by Mrs Bent on the spot.’ [The Queen, 7 December 1889]

1890 [The Bents in the Eastern Aegean and Turkey]

- 30th June: ‘Royal Geographical Society. Mr. J. Theodore Bent read a paper at the fortnightly meeting of of this society, held last night in the theatre of the London University, on explorations he had made in Cilicia Trachea.’ [Daily News (London), 1 July 1890]

- 22nd July: Theodore Bent reads his paper ‘Notes on the Armenians in Asia Minor’ to the Manchester Geographical Society [MGS, Vol. 6, 220-222]

- 5th September: At the meeting of the British Association at Leeds, in the Anthropology Section, Mr Theodore Bent read a paper on the Yourouks of Asia Minor, who, he said, were the least religious people he had ever heard of; but the religion honesty was deeply implanted their breasts. No more polygamous people existed anywhere, a Yourouk regarding himself as a disgrace unless he had six or seven wives. As a consequence womanhood bad sunk very low among them.’ [Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 6 September 1890]

1891 [The Bents are away all year exploring the remains at Great Zimbabwe for Cecil Rhodes]

- February (uncertain date): Theodore Bent lectures on the Castle Line Garth Castle on his way to Cape Town. [As recorded in Mabel Bent’s diary, 10 March 1891. Mabel does not give the title of the lecture]

1892 [The Bents return early in the year from South Africa, leaving for Ethiopia at the end of it]

- 22nd February: ‘At a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society, held in the theatre of the University of London last night, Mr. J. Theodore Bent read a paper entitled “Journeys in Mashonaland, and Explorations among the Zimbabwe and other ruins”’. [London Evening Standard, 23 February 1892]

- 2nd March: ‘Although Lord Randolph Churchill declined the [Tyneside Geographical] society’s invitation to lecture on Mashonaland, Mr. Smithson was fortunate enough to secure the services of Mr. J. Theodore Bent, one of the Council of the Royal Geographical Society and of the British Association. Mr. Bent and his wife embarked on an adventurous journey into Mashonaland, and conducted excavations and explorations among the Zimbaybe [sic] ruins —the supposed “Land of Ophir”. Mr. Bent will deliver his lecture on the subject next week – on Wednesday, March 2nd.’ [Lovaine Hall; admission charged is to be 1 shilling (c. £3) in main hall, and sixpence (c. £1.50) in the galleries!] [Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 26 February 1892]

- 23rd March 1892: ‘At the meeting of the Anthropological Institute to be held to-morrow evening, Mr. Theodore Bent will read a paper on the archaeology of the Zimbabwe Ruins, illustrated by the optical lantern [i.e. Mabel’s photographs]. I hear that Mr. Gladstone has expressed his intention to be present, and that Mr. Bent will on this occasion make special reference to the manners and customs of the early inhabitants of these remote regions of South Africa.’ [Birmingham Daily Post, 22 March 1892] [Bent was elected member of the Anthropological Institute at its meeting on 21 June 1892 (but not Mabel), see, Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, v.22, 1893, p. 174]

- Before 13 April: ‘Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent’s party was successful and interesting [at their London home]. Her sister, Mrs. Hobson, and few intimate friends assisted Mr. Bent and his fellow-traveller, Mr. Swan, in explaining the relics [of Great Zimbabwe] to the learned and unlearned, to the latter of whom the trophies… might otherwise have seemed just so many rudely carved old stones, instead of being silent witnesses of the ancient civilisation and worship traced out by Mr. Bent in the wonderful walled fortresses of Central Africa.’ [Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser, 13 April 1892]

- 5th August: At the meeting of the British Association at Edinburgh, in the Anthropology Section, Mr Theodore Bent read a paper on ‘The Present Inhabitants of Mashonaland and Their Origin’. [St. James’s Gazette, 6 August 1892]

- 7th September: At the 9th International Congress of Orientalists (opened in the theatre of the London University, Burlington-gardens), ‘Mr. J. Theodore Bent [in the Council Room of the Royal Geographical Society] gave an account of the more recent discoveries among the ruins of Zimbabwe and its neighbourhood.’ [London and China Express, 9 September 1892]

- 19th October: At a gathering of the Manchester Geographical Society in the Cheetham Town Hall, Mr. J Theodore Bent gave a talk on the Zimbabwe Ruins in Mashonaland. [Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 20 October 1892]

- 13th November: ‘Mr. Theodore Bent will deliver a lecture on “Mashonaland and the Ruins of Zimbabwe”, at the South Place Institute [Finsbury, London].’ [Colonies and India, 12 November 1892]

- 1st December: Mr. Bent lectured in Gloucester Guildhall, for the Literary and Scientific Association, on Mashonaland. [Gloucester Citizen, 7 December 1892]

- 7th December: ‘… at the Royal Spa Rooms, Harrogate. Mr. Theodore Bent, F.R.G.S., lectured on “The ruined cities of Mashonaland”, his interesting remarks being illustrated with excellent limelight views.” [Knaresborough Post, 10 December 1892]

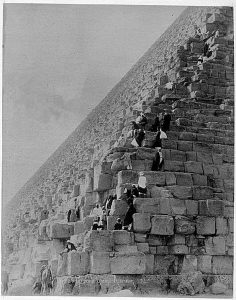

1893 [The Bents in Ethiopia until early spring, leaving for the Yemen at year end]

- 19th June: At the annual meeting of the Hellenic Society, ‘Mr. Theodore Bent spoke of his researches in Abyssinia.’ [The Globe, 20 June 1893]

- 18th September: At the British Association meeting in Nottingham, Mr. J. Theodore Bent reported ‘to the Committee on the Exploration of Ancient Remains at Aksum.’ [Nottingham Journal, 19 September 1893]

- 20th October: ‘Mr. J. Theodore Bent, the African traveller, delivered an address before the members of the Balloon Society, at St. James’s Hall [London].’ [London Standard, 21 October 1893]

1894 [The Bents make their first foray into the Yemeni interior, being home in the spring. They return to the region (via Oman) at the year end]

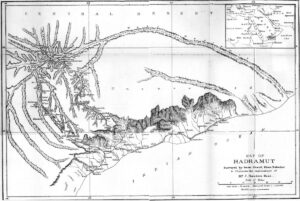

- 21st May: ‘There was an overflowing meeting last night… at the Royal Geographical Society [London] to welcome back Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent from their journeys in Southern Arabia.’ [St. James’s Gazette, 22 May 1894]

- 10th July: ‘At the London Chamber of Commerce, in the Council-room, Botolph-house, Eastcheap… Mr. J. Theodore Bent delivered an address on the expedition which he and his wife made last winter to the Hadramut Valley, South Arabia.’ [Home News for India, China and the Colonies, 13 July 1894]

- 14th August: At the meeting of the British Association in Oxford, ‘Mr. Theodore Bent read a paper on the natives of the Hadramaut in South Arabia.’ [St. James’s Gazette, 15 August 1894]

- 2nd October: ‘Mr. J. Theodore Bent lectured at a meeting of the Balloon Society on the subject of the explorations which he and Mrs. Bent made a few months ago in South Arabia, and the occasion was taken advantage of to present Mr. Bent with the Society’s gold medal.’ [Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 25 October 1894]

- 11th October: ‘Mr. Theodore Bent, F.R.G.S., who formerly resided at The Rookery, Low Baildon (now the residence of Alderman Smith Feather), delivered a lecture… at the Bradford Mechanics’ Institute, before the members of the Bradford Philosophical Society, upon his recent travels in Arabia.’ [Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, 19 October 1894]

- 25th October: ‘There was a numerous attendance at a meeting [of the Liverpool Geographical Society] held in connection with this society, at the Royal Institution, in Colquitt-street, last evening, when Mr. J. Theodore Bent, F.S.A., F.R.G.S., gave an interesting lecture on “The Hadramaut: a journey in Southern Arabia,” which was illustrated by a series of photographic slides.’ [Liverpool Mercury, 26 October 1894]

1895 [The Bents return from the Hadramaut coast in the spring and leave for the Sudan at the year end]

- 6th June: ‘Mr. J. Theodore Bent read last night a paper on “Journeys in Southern Arabia” in the Lecture Hall the University of London.’ [St. James’s Gazette, 7 June 1895]

- 12th June: ‘Lord and Lady Kelvin received a brilliant and distinguished company last night in the rooms of the Royal Society in Burlington House’, when the Bents presented photographs and finds from Southern Arabia. [St James’s Gazette, 13 June 1895]

- 1st July: ‘Mr. J. Theodore Bent delivered a lecture at the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, at Hanover-square… The lecturer dealt with the Hadramaut, and Dhofar, the frankincense and myrrh countries.’ [Globe, 2 July 1895]

- 18th September: ‘At the close of the British Association meeting at Ipswich, Mr. Theodore Bent gave a paper on “The Peoples of Southern Arabia”.’ [St. James’s Gazette, 19 September 1895]

- 7th November: The Royal Scottish Geographical Society – Glasgow Branch. The Anniversary Address will be delivered in the Hall, 207 Bath St… at 8 o’clock , ‘by Mr. J. Theodore Bent, on “Southern Arabia”. Sir Renny Watson Chairman of the Branch will preside. Admission only by Ticket, two of which have been forwarded to each Member of the Branch.’ [Glasgow Herald, 6 November 1895]

- 8th November: ‘In connection with the Royal Geographical Society, a lecture was delivered… by Mr. Theodore Bent, in the National Portrait Gallery, Queen Street [Edinburgh]. The subject of the lecture was Arabia, and it was illustrated by lime-light views. There was a good attendance.’ [Edinburgh Evening News, 9 November 1895]

1896 [The Bents return from the Sudan in the spring and leave for their last trip together, to Sokotra and Aden, at the year end]

- 1st June: Mr. Bent read a paper on the Sudan to the Royal Geographical Society, London.

- 13th October: Mr. Bent lectures on Arabia at the Royal Victoria Hall, London. [South London Press, 17 October 1896]

The above, it seems, was Theodore Bent’s final lecture. The lantern flame flickers and disappears.

For some background, see also a reference to the Bents, in Emily Hayes, Geographical Projections: Lantern-Slides and the Making of Geographical Knowledge at the Royal Geographical Society C. 1885–1924. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Exeter, 2016, p. 342.

Return from Note 1

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article