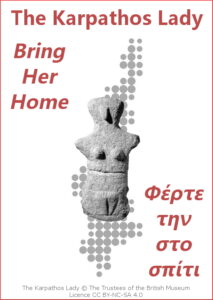

Travel writer Alan King falls for the ‘Karpathos Lady’, kindly allowing followers of the Bents to share his own fascination for her… It makes quite a story!

On the Turkish-controlled island of Karpathos, shortly before midday on Monday, April 20th, 1885, a 6000-year-old female figure, hidden under a carpet, carried on the back of a man from Anafi, was smuggled onto a ship in Pigadia harbour, never, to this date, to return to her island home.

This is the story of her kidnap and of how she later travelled the world under her new name of the ‘Karpathos Lady’.

The Kidnap and Travels of the Karpathos Lady

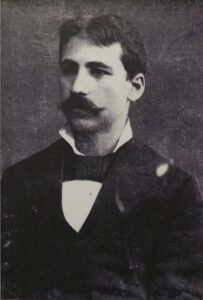

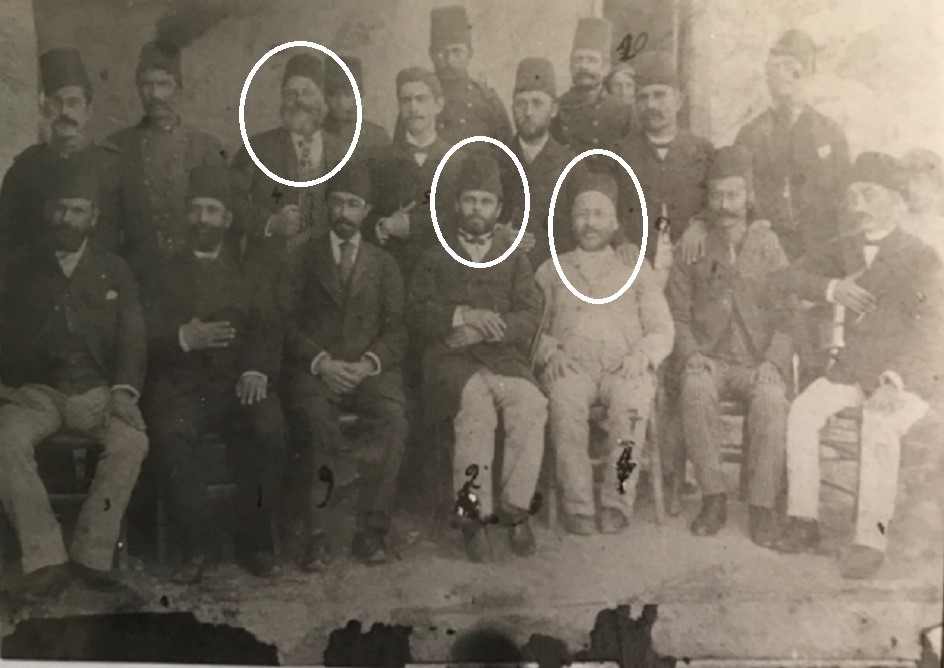

The kidnappers

© The Bent Archive

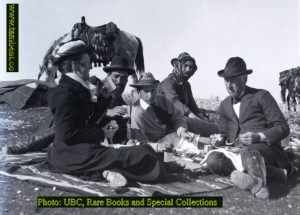

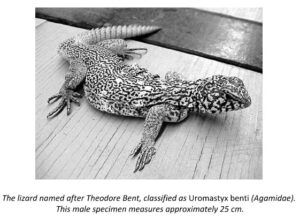

During the winters between 1882 and 1890, the British travellers Theodore and Mabel Bent would leave their home in London’s fashionable West End to meander around the Greek islands and the Turkish coast in search of adventure in the exotic Levant. Theodore Bent’s main interest was archaeology and their itinerary would be designed to take them to locations where there were opportunities to excavate new sites.

In March and April, 1885, they visited the island of Karpathos and came upon a limestone statue of a naked female, baring all. When they left the island, six weeks later, the Karpathos Lady went with them.

A desert diversion

Three months before, in mid-January, the Bents had travelled from London to Dover where they boarded a ferry to Calais to connect with the train which would take them on the first stage of their latest adventure.

Travelling via Paris, they reached an uncharacteristically snowy Marseilles on January 14th and the next day were on board the M.M. Tage heading for the somewhat warmer climes of Egypt, where they arrived 7 days later.

It was a birthday jaunt for Mabel who, on January 28th, climbed a pyramid at sunset and later wrote: “It was splendid being up there and I think it very very unlikely that any other person has been up by moonlight on his birthday before … it felt odd to be alone with the Pyramid and the moon.” note 1

World Enough, and Time: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral – All Mabel Bent’s quotes in this article can be read in full in Gerald Brisch’s excellent transcription of Mabel’s chronicles, the informal diary entries she made throughout their adventures in Greece and Turkey.

World Enough, and Time: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral – All Mabel Bent’s quotes in this article can be read in full in Gerald Brisch’s excellent transcription of Mabel’s chronicles, the informal diary entries she made throughout their adventures in Greece and Turkey.Arrival in Karpathos

Mabel was clearly over the moon about her 38th birthday celebration, however, there was another motive for the Bents travelling to Egypt. With their ‘holiday’ over, they had work to do and February 4th saw them aboard the S.S. Saturn, bound for the island of Rhodes, although Bent’s sights were really set on excavating on neighbouring Karpathos.

He’d become aware of four potential dig sites on Karpathos. However, the Turks were cracking down on such unlicensed archaeological activities. In addition, after the publication of his article in 1883 about the islands of Chios and Samos note 2 , in which he criticised Turkish rule, he feared he would have difficulty obtaining the necessary travel permits for the islands he wished to visit. At that time, Egypt was still effectively Turkish territory and Bent figured that he would more easily slip into the Turkish-occupied Greek islands from Egypt rather than the usual point of entry of Istanbul.

In the event, when the couple reached Rhodes, it became evident that the Turkish governor, or Pasha, Khamel Bey, was going to make life difficult for Bent. Not surprising really; at the time of Bent’s critical article about Chios and Samos, Khamel Bey had been Pasha on the nearby island of Lesvos and had become embroiled in the fallout from the article.

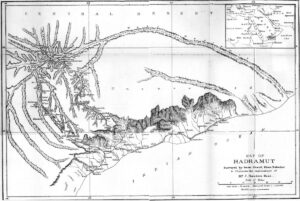

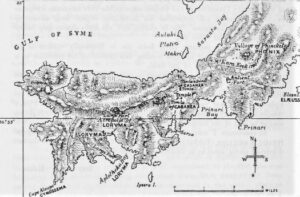

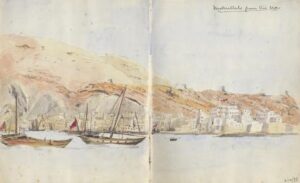

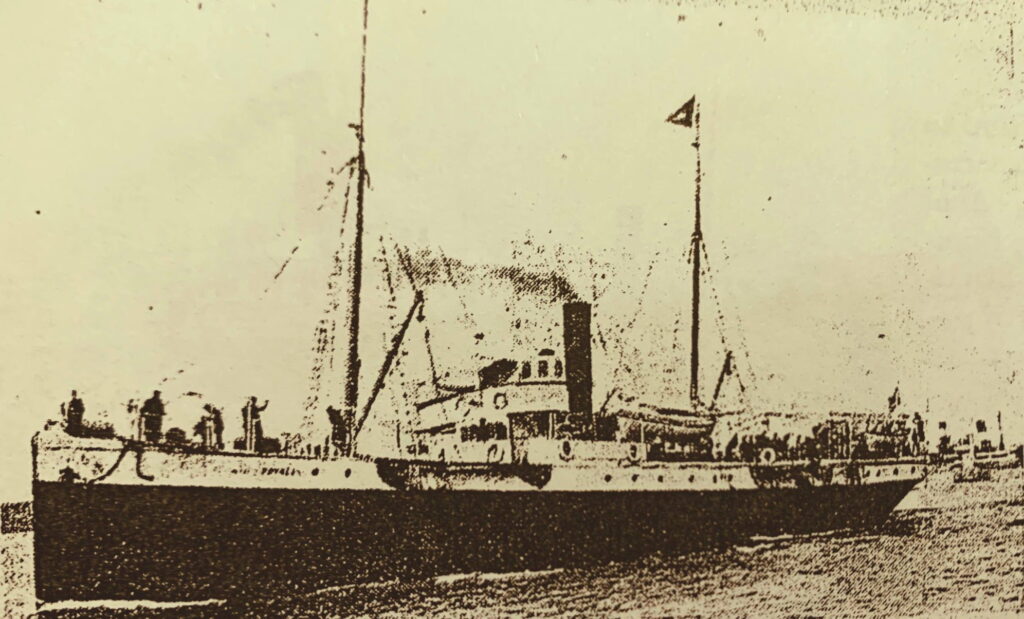

Khamel Bey refused to allow them to travel to Karpathos on the Turkish government steamer and the couple were forced to take a circuitous, clandestine route using the Greek steamer Roúmeli and small local caiques. After stopovers on the islands of Nisyros and Tilos, they finally made landfall on Karpathos, at Tristomo Bay, in the north of the island, on March 6th, 1885.

The Karpathos Lady appears

The main town of Pigadia had been their intended destination, but after an horrendous 9-hour overnight voyage from Tilos, bad weather forced them to take shelter in the wide, protected bay of Tristomo before continuing on their way next morning. But bad luck dogged them again. Two sudden gusts of wind took the sail and mast overboard and they just managed to limp into the small harbour village of Diafani where they found another boat and crew to continue their journey south. After a further seven and a half hours, they reached Pigadia, not far short of two whole days after having left Tilos, just 100 kms distant.

Bent was to encounter yet more problems. It seems that word from Rhodes had preceded his arrival on Karpathos and the Turkish authorities were aware of his intentions. Under scrutiny from the Turks, he found it difficult to excavate on Karpathos as he’d planned; he wrote while in Pigadia: “Here there are evidences of pre-historic inhabitants, the graves of whom I was unfortunately unable to open owing to the presence of the Turkish authorities …”

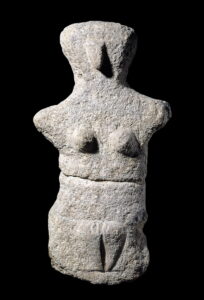

At this point however, Bent seemed unaware that he already had in his possession the most important object of his entire mission on Karpathos. His somewhat downbeat sentence above continues: “… but I was able to obtain a large stone figure of a female idol.” note 3

The Karpathos Lady had appeared. Her fate was now sealed.

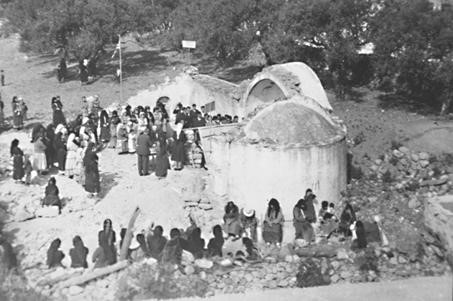

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Evading the Turks

Bent left the statue in Pigadia with the man who’d sold her to him, planning to collect her when he finally left the island.

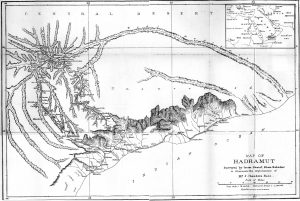

He’d been hoping to excavate the sites of the four ancient cities of Karpathos. With Posidonia and Arkessia in the south of the island effectively off the agenda, his only recourse was to travel to the isolated north, well away from the inquisitive eyes of the Turks, to investigate Vrykounda on the north-west coast and the presumed site of Nisyros on the islet of Saria.

Shortly before Easter, in preparation for their journey, they arranged to leave some of their baggage in store in the Custom House in Pigadia with the aim of collecting it as they departed the island some weeks later. Of course, one very important item, the Karpathos Lady, was already in Pigadia, awaiting collection at the house of the man who’d sold her to Bent.

Their digs at Vrykounda yielded some interesting finds which later ended up in the British Museum.

The kidnap

Their excavations in the north of the island completed, they returned again to Diafani and set out from the village in a small boat for the journey south to Pigadia to retrieve their stored baggage, and, of course, the Karpathos Lady. They planned to take the Greek steamer, Roúmeli, from Pigadia, which would carry them out of Turkish jurisdiction to Greece, but, to their horror, shortly after leaving Diafani, they saw the steamer heading north toward Diafani. Incredibly, they managed to flag it down by waving their umbrellas so that the captain would know they were the British passengers he’d taken from Rhodes to the island of Nisyros some weeks before. The Roúmeli had already called at Pigadia and was en-route to Diafani before proceeding on to the island of Kassos. They persuaded the captain to return, after Diafani, to Pigadia, with the help of 13 British pounds (some £800 or €900 at today’s value), much to the annoyance of some the passengers already on board.

© Andreas Michalopoulos 2010

Mabel’s diary account takes up the story of what happened when they arrived in Pigadia and how their loyal Greek dragoman, Manthaios Simos from Anafi, was given the special task of retrieving the 40kg statue while Bent kept the Turks occupied with “much raki”:

“Manthaios set off to run to the house where was a very hideous statue, more than the size of a baby, half a mile off. Theodore and the Turks sat down at the café … At last I saw Manthaios tearing back with the burden [of 40kg] on his shoulders and very soon they reached the ship and all was on board . . . we were safely off . . . ‘Oh!’ I could not help exclaiming ‘How thankful I am to be under the Greek flag’. And indeed with 3 umbrellas in the cabin, though all in disrepair, what now had we Britons to fear from Turks?”

“We sat down to luncheon at 12 in gay frame of mind and then I heard how Manthaios had run to the house and found it locked and had broken the door open, found the statue, wrapped it up in what he carried for the purpose, and ran back. Theodore was in the meantime drinking much raki with the Harbourmaster and other Turks, having been to the custom house and told an old woman to take a long time carrying the things, one by one, very slowly to the boat and thinking Manthaios would never be back; as I could see Manthaios I was luckier. When Manthaios appeared, Theodore could see that the statue showed behind and told him so, but Manthaios said ‘No matter’ and rushed on to the boat and then went back to say goodbye to the Turks. Theodore saw them spot the statue and whisper together and shrug their shoulders“.

The raki had done its job well!

Mabel continues: “… so now we are in possession of the most hideous thing ever made by human hands.”

So thought Mabel of the Karpathos Lady. If only she could have known that, 130 years later, the beauty of this “very hideous statue” would finally be recognised for all the world to see.

The odyssey begins

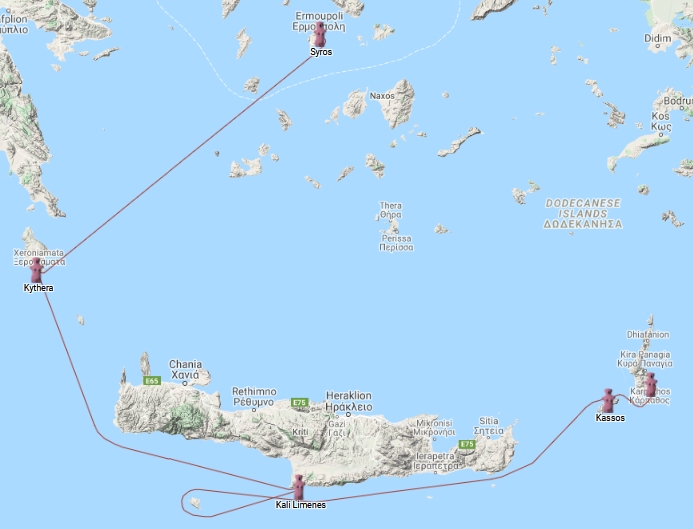

© Google Maps

Passing to the south of Karpathos and after a 3-hour stop in Kassos, the captain of the Roúmeli set a course for the next stop on the escape route from the Turks, the Greek island of Kythira, aiming to sail across the Libyan Sea, parallel to the southern coast of Crete, before steaming north and out of Turkish-controlled waters. (Incidentally, the Bents never opted to explore Crete, although we know Mabel spent the winter of 1899/1900 there. Perhaps the work of Arthur Evans on the island dissuaded them.)

During the night, some hours after leaving Kassos, maybe in fury at the loss of a goddess he might have sought to seduce, the great god Zeus unleashed his winds upon the Roúmeli and her passengers. Mabel wrote: “We had a fearful night of storm, pitching, rolling … and fears of falling on the floor … Much splashing took place and water flew over the ship”. Roúmeli battled bravely on, but next morning, close to the island of Gavdos, the captain was forced to turn the ship around and head back for the shelter of Kali Limenes (Fair Havens), at the most southerly point in Crete, where the ship carrying St. Paul, on his journey from the Holy Land to Rome, is said to have rested before encountering its own winds near Gavdos: “a tempestuous wind, called the northeaster, struck down from the land … and no small tempest lay on us”. note 4

© Google Maps

Arriving at the safe haven of Kali Limenes in the early afternoon of Tuesday, Roúmeli waited out the storm until 8 o’clock in the evening, when the winds abated sufficiently to allow the captain to continue on through the night. Wednesday morning saw them off Paleochora, the most westerly outpost of Crete, before Roúmeli turned north, finally entering the safety of Greek waters, close to the island of Antikythira, at 10 o’clock. A sigh of relief must have been breathed by Bent and Mabel.

At midday, the Roúmeli docked at the Kythira port of Kapsali. The Karpathos Lady had made it to Greece. Sadly, her stay was to be lamentably short.

During the few hours’ stopover in Kythira, the Bents arranged for papers to be drawn up to cover the true origin of the Karpathos Lady. Mabel tells us: “At Kythera a ‘manifesto’ was made and signed by the captain, saying he had picked us, and our cases, up in Turkey, and by the Kythera customs people to say we had not started from there.”

© Google Maps

From Kythira, sailing overnight, Roúmeli arrived at her home island of Syros on Thursday, April 23rd, and the Bents checked into their usual haunt of the Grand Hôtel d’Angleterre from where Bent wrote to the Keeper of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum:

We returned from Karpathos yesterday and had hoped to catch a steamer which would have brought us and our things straight to England. Unfortunately we shall have to wait a week at least, and as we have so much plunder we cannot take the Marseilles route … but of course now we shall not reach England till the middle of May. We were fairly successful in Karpathos, finding a large number of rock cut graves unopened which have produced pottery, etc … I have likewise got a good-sized statue of one of those quaint figures which I got at Antiparos last year; it is of stone and nearly a yard long.

That “good-sized statue” was, of course, the Karpathos Lady, who spent the final few days of her time in Greece locked up in the Custom House in the port town of Ermoupoli, where the Bents often stashed their “plunder”.

It was not until some 10 days later that the Bents found a ship that could take them at least part of the way on their journey home. And so – the Karpathos Lady finally left Greek soil from the island of Syros at 07:00 on Saturday May 2nd, 1885, never, to this day, to return.

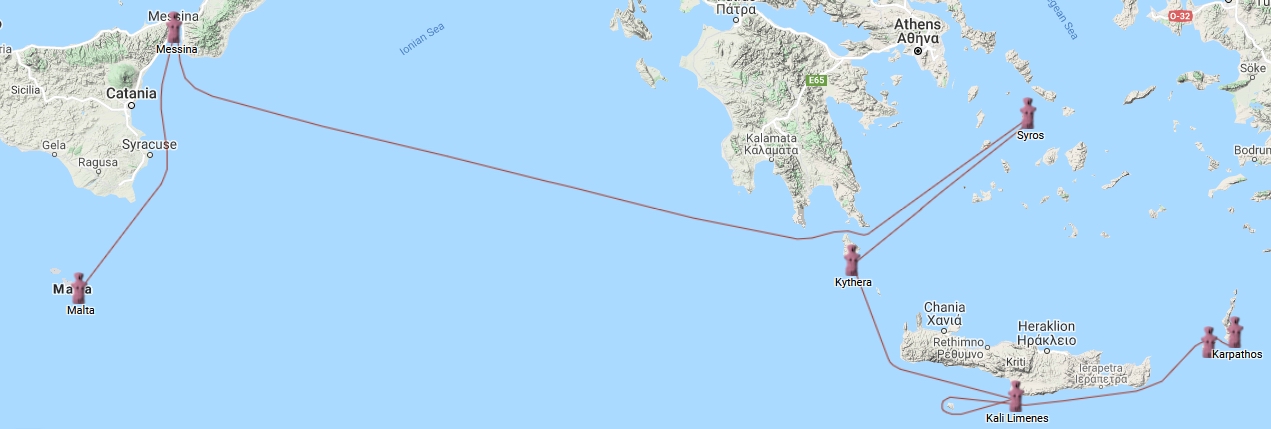

The M.M. Erymanthe took them from Syros to Messina in Sicily where, with fortuitous timing, they boarded the Maréchal Canrobert for the overnight leap south to the British colonial island of Malta, a busy staging post on the route between Britain and its colonies in the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

© Google Maps

In Malta, they found it “not so easy to find a ship for London as we had thought, most of them being crowded at this season, and lots of people waiting for passages.” It was 6 days before they could secure a passage, with less than an hour’s notice, on Friday May 8th, on the cargo ship Restormel, carrying grain from Odessa to London.

One final act of subterfuge was necessary: “[The Restormel] is not a passenger ship and we are to be smuggled into the chartroom and there concealed; when we reach London our baggage to be supposed to be travelling alone”.

Sometime around May 20th, 1885, the Karpathos Lady finally landed on British soil, a month, and almost 7,000 km, after her odyssey had begun on the back of the Bents’ man-servant in Pigadia.

© Google Maps

Mabel’s final entry in her chronicle for the adventure they’d embarked upon four months earlier reads simply: “We reached home via Millwall Dock in safety with our 24 pieces of the most varied luggage, and I am more convinced than ever that there is no place like it.”.

Descent into the Underworld

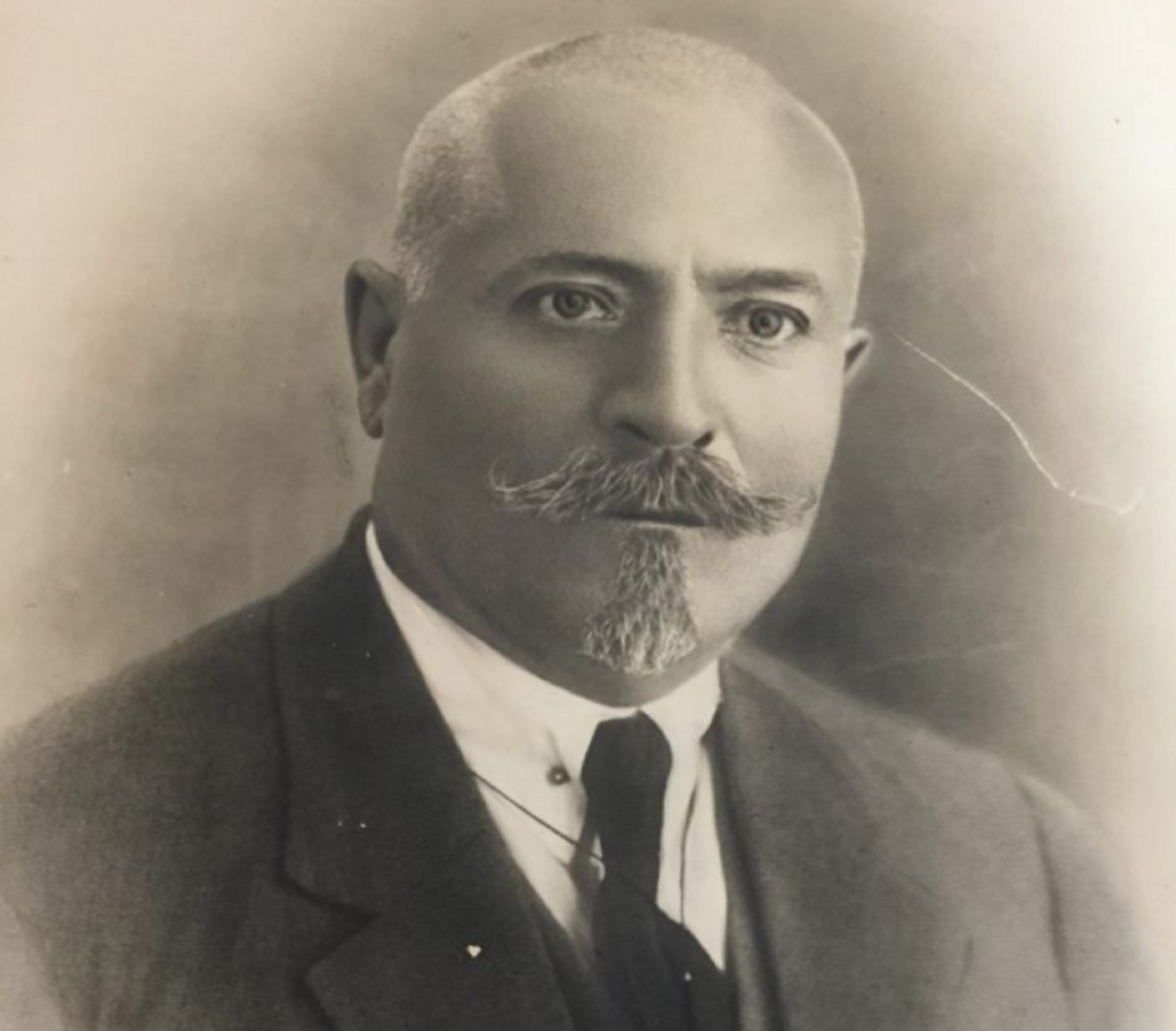

Given Mabel’s opinion of the statue, it’s hard to think that the Karpathos Lady would ever have been a house guest or graced the entrance hall of the Bents’ home near London’s Oxford Street. Indeed, Mabel may even have been more forceful about the ‘other woman’ in her husband’s life, for we know that, a year later, the Karpathos Lady was sold by Bent to the British Museum.

Alas, there her odyssey faltered, and for the next 110 years or so, the Karpathos Lady was consigned to the dingy basement of the British Museum to confront her shades, hidden from public view, despite her then being, and still remaining, the oldest Greek statue in the Museum’s collection!

Rebirth – the odyssey continues

After over a century of confinement in the ‘Underworld’ of the British Museum, the Karpathos Lady finally emerged into the daylight of the modern world. Her ‘rebirth’ came when her beauty was recognised by Dr. Peter Higgs, the Curator of the Department of Greece and Rome at the Museum. Dr. Higgs told us “The Karpathos Lady – a grand name for a wonderful object (if not to everyone’s taste). I can hold my head up high and admit that I brought her out of obscurity where she was languishing unloved in the basement and persuaded my colleagues to put her on display. Now she has toured the world!”

Thanks to the keen, professional eye of Dr. Higgs, the Karpathos Lady remained on display for a number of years, bringing pleasure to the many millions of visitors to the Museum.

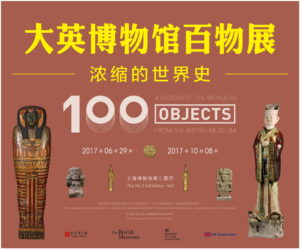

In January 2010, BBC Radio 4 broadcast the first of a 20-part weekly series, produced in conjunction with the British Museum, entitled ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’. The series met with great critical acclaim and the Museum embarked upon creating a touring exhibition based on the objects featured in the radio programme.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Inexplicably, the Karpathos Lady was not included in the BBC Radio series, nor did she become part of the initial touring exhibition. However, after the first exhibition venue in Abu Dhabi in 2014, her beauty and importance were once again acknowledged and she replaced another exhibit as a permanent member of the touring exhibition. Her debut, later that year, was in Taipei, Taiwan – her first journey outside Europe. Japan followed in 2015 with exhibitions in Tokyo, Kyushu and Kobe. She jumped continents in 2016 and visited Perth and Canberra in Australia before heading back to Asia in 2017, where she wowed them in Beijing and Shanghai; Beijing attracted 340,000 visitors and Shanghai 8,000 visitors on its first day alone. 2018 saw her back in Europe for the exhibition in Valenciennes in France. In May 2019, she returned to Asia for a 4-month gig at the Hong Kong Jockey Club where the organising Hong Kong Heritage Museum highlighted the Karpathos Lady as one of the top exhibits – an accolade indeed for an object that had been almost overlooked.

All a long, long way – and a long, long time – from her Karpathos home.

Return to her Ithaka

Since her return to London from Hong Kong, the coronavirus pandemic has clipped the wings of many a traveller, the Karpathos Lady included, but our hopes are high for her further, future travels.

The travels of the Karpathos Lady have not, to date, included Greece, where she would surely be welcomed as a home-coming heroine. However, maybe one day, she will finally find her way back to her very own Ithaka – her island home of Karpathos.

‘Bring Her Home’ – sign the petition

The Archaeological Museum of Karpathos in Pigadia dedicates a small part of a display cabinet to an artefact which should be the pride of the island and its people. How appropriate it would be if the REAL Karpathos Lady could be proudly displayed for all to see.

With this in mind, we’ve started a campaign aiming to persuade the British Museum and the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports to negotiate the loan of the Karpathos Lady to Greece. The idea is for a ‘summer season’ in Pigadia, hopefully in 2022, where tourists and locals alike could admire the beauty already seen by so many across the world, establishing her rightful role as an icon of the island of Karpathos.

Please visit the ‘Bring Her Home‘ web page to ‘sign’ the petition to be sent to the British Museum and the Greek Ministry – it takes less than a minute. Why not tell your friends about the campaign and get them to visit the web petition page? http://karpathoslady.click

#karpathoslady

Interactive map of her travels

2014-2015 December 13-March 15 National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

2015 April 18–June 28 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

2015 July 14–September 6 Kyushu National Museum, Dazaifu, Japan

2015-2016 September 20-January 11 Kobe City Museum, Kobe, Japan

2016 February 13-June 18 Western Australian Museum, Perth, Australia

2016-2017 September 8-January 29 National Museum of Australia, Canberra, Australia

2017 March 1-May 31 National Museum of China, Beijing, China

2017 June 29-October 8 Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China

2018 April 19-July 22 Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes, France

2019 May 18-September 9 Hong Kong Jockey Club, Hong Kong

The essential data

Description: Limestone female figure.

A thick slab worked flat, with beak nose, pointed breasts and vulva triangle left in high relief on the front. The eyebrows are marked by incised lines. Above the slit in the vulva triangle are four incised lines to represent the pubic hair; below is a horizontal groove.

Function: Her stylised form is very striking and raises many questions, as her original significance remains a mystery. One possibility is that she is a fertility goddess, testimony to the importance of female fertility at this time.

Cultures/periods: Neolithic (late)

Production date: 4500BC-3200BC

Excavated/Findspot: Bourgounte (Vrykounda), Karpathos, Greece

Materials: Limestone

Height: 660 mm

Width: 354 mm

Depth: 200 mm

Weight: 40 kg

Condition: Broken off below the hips. Rejoined below breasts.

Purchased from: James Theodore Bent

Acquisition date: 1886

Conservation: January 8, 1998. Remove dowel and base, light clean. Reason: Permanent Exhibition. Removed object from base and dowel from object mechanically aided by hot water to dissolve the plaster. Slightly cleaned with Wishab sponge (vulcanized latex, filler).

Leave a comment

We welcome your comments on this article or any questions you may have about the information we’ve presented here. Any further information you may have about this story would be gratefully welcomed.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this articleArticle ©2021 copyright Alan King. All images copyright Alan King unless otherwise stated.

Notes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

For all the Bents’ travels around the Dodecanese, see Further Travels of the Insular Greeks (Archaeopress, Oxford).