“He modelled but sparingly for bronze…” (Kineton Parkes 1921: 111)

“… one of the best of the pure sculptors of the Nineteenth Century Renaissance, a man who loved his work with all his heart and soul, and one who loved his fellow men.” (Kineton Parkes 1921: 112)

“It is certainly for his power of telling a story beautifully… that Mr. Lee will continue to be admired.” (Spielmann 1901: 66)

An introduction to a rediscovered and previously unpublished, cire perdue, cast bronze, wall relief/large medallion by the Arts & Crafts/New Sculpture master, Thomas Stirling Lee (1857-1916).

The commission

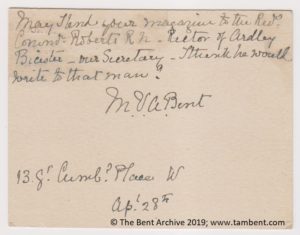

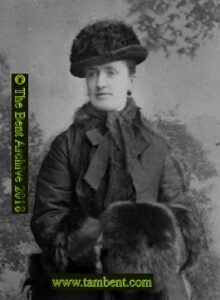

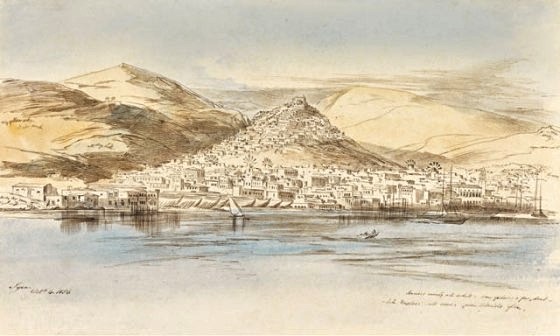

“Mr. T. Sterling Lee is at present engaged on a bronze bas relief of Mrs Theodore Bent, who is spending the season at her London house.” (Lady of the House, Saturday 15 June 1895)

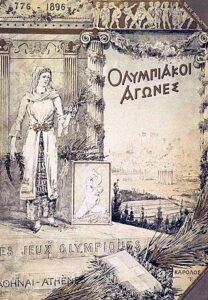

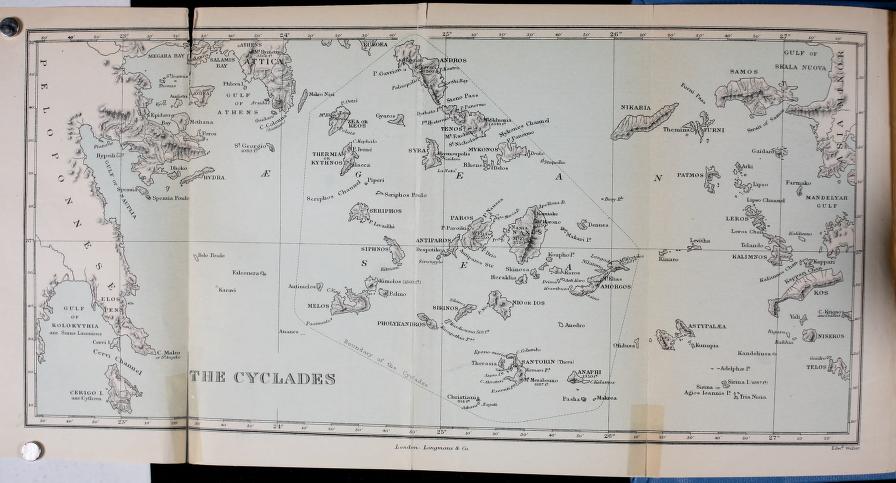

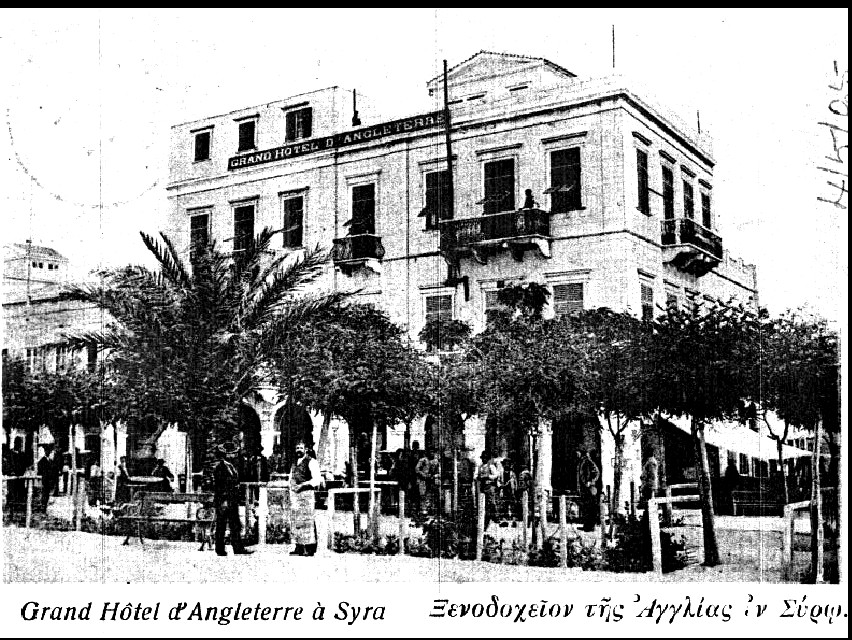

By the mid 1890s, Theodore and Mabel Bent had become celebrities; they had amazed London with their fifteen-year campaign of explorations and discoveries in large areas of the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and the Middle East, which, regularly updated in the media, had captivated a huge, international audience. Bent had produced countless articles and scholarly papers, as well as six books; the couple gave regular talks and lectures (often with lantern-slides reproduced from Mabel’s photographs) to various institutions and at popular events; the British Museum had hundreds of their acquisitions. Their personal collection in London was often on show to the public; they were sought after by editors for interviews, Mabel featuring equally with Theodore.

It is not surprising, therefore, that, as well as the couple appearing at the leading studio photographers for their portraits, Mabel should also have approached, or been approached by the innovative British sculptor and artist Thomas Stirling Lee (TSL, 1857-1916) for her relief likeness, opting for a roundel (‘medallion’) in bronze. Presumably she must have gone to TSL’s studio, in Chelsea Vale, with its small foundry en suite, to sit for him. He would have been paid for this commission certainly; at an exhibition some years later he was asking 10 guineas (c. £750 today) for medallions of idealised themes (Leeds City Art Gallery Exhibition, 1909). It is not known to date whether TSL also produced a likeness of Theodore Bent. note 1

The two bronze reliefs of Mabel Bent

The 1895 relief (confidently attributed to TSL) has (June 2024) been acquired by the friends of the Bent Archive and features above. Facing right, the sitter’s features are handsome and strong, her famous red hair coiled, her chin ready to face the travel challenges ahead, her nose a compass needle, due East; her name, Mrs J. Theodore Bent, runs boldly clockwise, with the date – 1895; the TSL monogram stands out, bottom left (the combined letters ‘TSL’ and a series (3 or 4) of knobs on the rim before the lettermark). Sculpted and cast by TSL in bronze; maximum width 260 mm; weight 1.86 kg.

The 1896 relief is today in private hands and is not illustrated here note 2 . It is essentially a reworking of the 1895 version. Again facing right, this time the features are softer, as if Mabel had requested a perhaps less assertive appearance; as if the 1895 relief were sculpted en-scène, in the intense heat of the Wadi Hadramaut, for example, while the 1896 version comes demurely from her London drawing-room at 13 Great Cumberland Place, perhaps while giving an interview, over tea and sandwiches: Mabel as Britannia. Once more, her famous red hair is coiled high, her name runs clockwise, with the date – 1896; the TSL lettermark and characteristic knobs also appear, bottom left. Sculpted and cast by TSL (dimensions and weight n/a at present).

In terms of the two dates (1895 and 1896), it is difficult, without documentation, which might appear, to give the exact times when TSL (or Mabel Bent) might have been working on the sculpting and casting the reliefs. Over these years, Theodore and Mabel were exploring east and west of the Red Sea. Mabel may have been available for the modelling in the late spring and summer, when they habitually returned to their London townhouse before undertaking family visits to the north of England and Ireland.

TSL was a regular contributor to the Royal Academy and the 1896 event included ‘Five medallions, bronze’. It would be good to think that with these might have been one of the reliefs of Mabel Bent (Graves 1905: 21).

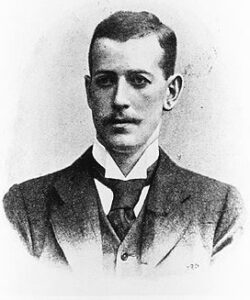

The sculptor – Thomas Stirling Lee (1857-1916)

Stirling Lee’s story is romantic and poignant – the admired but unfulfilled artist – working at the turn of Victoria’s century, pulled here and there by the various stylistic waves reaching both sides of the Channel. A most highly regarded, likeable and clubbable personality by all accounts, TSL was one of the founders of the Royal Society of British Sculptors, and the Chelsea Arts Club in 1891.

There is a great deal of background data on TSL online, including his works, as one might expect; for now, some sympathetic paragraphs from Kineton Parkes (1921: 111-113) provide a maquette:

“THERE are sculptors to-day, and of the immediate past, who acknowledge no influences, and who, moreover, deplore the training they received: men who stand alone and apart from all groups, schools and associations. Sometimes their work is so individual as to call for this isolation, sometimes it is more or less in conformity with the work of the academies, and definitely resembles the products of the schools. Still, these artists, possessing an individualistic and egoistic personality strongly developed seem to differentiate from their fellow-artists and to form a heterogeneous class of their own. Such an one was Stirling Lee…

“Thomas Stirling Lee was one of the most retiring men and most modest artists I have ever known. He was always willing to talk about art, but he seemed to do it from an impersonal standpoint, while, paradoxically, he was a most personal artist, and held emphatic opinions on the art of sculpture. He carved directly in marble and stone, and he modelled but sparingly for bronze. His work of earlier years may be seen in the panels decorating the St. George’s Hall at Liverpool, blackened but not obliterated by the atmosphere of that great city of dreadful noise.

“His later panels are in the Bute Chapel of Bentley’s great cathedral at Westminster. Between those two sets of works he produced busts and reliefs: portrait and ideal. His work was plain, but it was distinguished. It had little ornament, but it was not severe to the point of being undecorative: it was indeed sympathetic. I remember a bust of a girl’s head – it is in the Art Gallery of the Nicholson Institute at Leek, in North Staffordshire – which is full of tenderness, and there are others just as sympathetic. A series of small bronze portrait plaques of his friends of about 1889 shew how friendly a man Stirling Lee was [our emphasis]. If he was retiring, he was also brotherly, as the members of the Chelsea Arts Club (of which he was a founder, with Whistler and some few others) well remember. He was a great worker, and one of his most ambitious pieces was one of his least successful, his Father and Son, the reception of which greatly disappointed him.

“There are dangers, as well as virtues, in being too modest, as well as in direct carving: they may be your undoing, and I believe, combined, they were in Stirling Lee’s case. To the grief of his friends, he died suddenly in South Kensington station, in one of the years of the war, and there passed away then one of the best of the pure sculptors of the Nineteenth Century Renaissance, a man who loved his work with all his heart and soul, and one who loved his fellow men. His studios were always in Chelsea: in Manresa Road, in the Vale, and, when the Vale disappeared, then he had built for himself the studio in the Vale Avenue, where his Westminster Panels and his Father and Son were carved. One of his last exhibited works was his marble bust called Beatrice, at the Royal Academy. There is a beautiful bust, full of thought, of a girl in the Bradford Museum, and an equally fine bust is that called Lydia, which was seen in the special Exhibition by the Chelsea Arts Club at Bradford in 1914.” note 5

Richard Dorment (1985: 24) is another writer to comment on the sculptor’s good nature, referring to ‘the sweet-tempered Thomas Stirling Lee’, prepared to follow his brother sculptor Alfred Gilbert ‘to Rome and back to London’.

Puccini but without the tunes

For a glimpse of some aspects of artistic life in the late 19th century, and the founding of the Chelsea Arts Club, including the involvement of TSL, see Arthur Ransome’s (he of Swallows and Amazons) Bohemia in London (London, 1907)… But a more entertaining and feathery work (a novel) exists, Puccini but without the tunes, written by Morley Charles Roberts (1857-1942), very much larger than life and on the periphery of the Chelsea scene in the late 1880s. The characters are thinly disguised and ‘Mr West, the sculptor’ can confidently be taken as a model for TSL. Some references from it are welcome here – and not without with charm: “Across the narrow lane was another long studio, occupied by West the sculptor, to which was attached a shed containing works in progress and others long past hopes of sale, while at its northern extremity a bronze-casting furnace sometimes shot at night a blue flame far above its iron chimney”… and, later “… under the table was a terracotta bust of herself [the model, Miss Mary ‘Priscilla’ Morris] by West, and on it a medallion as well.” (Morley Roberts 1890: 19-20, p. 93 for the medallion; the emphasis is ours). Did Morley perhaps see the bronze roundels cast by Stirling Lee for some friends around this date? (Kineton Parkes 1921: 112). Indeed, was Morley Roberts one of the sitters? In any event, this seems to have been the period when TSL began to produce them – within his small foundry in Chelsea Vale.

Morley Roberts also provides a physical description (of West = TSL?), and let’s take it as fairly accurate: “For no one could meet West once without liking him… [He] was a man of the middle height, very strongly built and powerful in the arms from continually using the hammer when working in marble, with a very bright and pleasing face, which indicated both sensibility and refinement. His eyes were almost sparkling in his merrier moods, but grew intense and solemn in the rarer moments when he spoke out to some sympathetic soul what a man usually keeps silence about, his hopes and desires, his aims and methods, his feeling for nature, for the world and man. For he was intensely spiritual under a thin cover of materialism, and gloried in his art, which he held to be based on Truth and Right, as both consolation and reward of the worker.” (Morley Roberts 1890: 77-9). In ‘Thomas Stirling Lee, the first Chairman’ by Geoffrey Matthews, Chelsea Arts Club Yearbook 2022, there is a photograph of TSL capturing much of what Morley Roberts finds in him.

More on medallions

Although with a long and distinguished presence, in various media, the vogue for medallions seems to have come to the fore again in the first half of the 19th century – actual likenesses and idealised themes – epitomised in the work of Pierre-Jean David d’Angers. (Note that ‘medallion’ can also refer (Jezzard 1999: 99) to “larger wall plaques, memorial plaques, memorial tablets, wall tablets, commemorative medallions, medallion portraits and medallions.” Larger productions, weighing 2 kg or more, could be encased within bespoke wooden frames for wall-mounting.)

In Britain, following the work of William Wyon (1795-1851) , the French-born artist Alphonse Legros (1837-1911) is widely seen as leading the late 19th-c revival of the medallion – favouring metal casting, pouring molten media into hollow forms. Among his preferences was to send initially his forms to Paris, where the art was perfected, and avoiding finishing effects, such as smoothing the circumference and polishing, thus eschewing the neo-classical tradition and pointing towards the Arts and Crafts movement. It can be said that Thomas Stirling Lee was an apostle in terms of his relief modelling and casting of portrait roundels (Attwood 1992: 4-10).

Bronze relief plaques (medallions) by TSL seem to be rare, perhaps a ‘hobby’ and distraction, pocket money. It is more than likely that the medallions/reliefs TSL produced for his friends and clients remain with the families – personal things that do not shout out for publication or exhibition.

What follows are the results of online searches, only, for examples of TSL’s medallions; but it is some sort of a beginning for more dedicated research by historians, if they are so minded.

Of course, if you have one we would be delighted to hear – and perhaps the series can be assembled for a TSL retrospective one day: indeed, 2026 will mark the 110th anniversary of his early death.

As well as the two reliefs of Mabel Bent (1895 & 1896) already referred to, other known examples of TSL medallions include one Walter Sickert note 3 roundel in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge [M.17-2006; dated c. 1882; bronze; 158 mm; facing right; the name ‘SICKERT’ in raised letters along viewer’s right edge of the roundel]; the (?) Herbert Goodall roundel in the British Museum; the Mrs Rodney Fennessy roundel in the V&A, London [A.5-1973; 1889, 250 mm; bronze; facing right; the name ‘Mrs Rodney Fennessy’ running around the right edge].

The V&A also have a TSL medallion of Sickert [A.6-1973; undated; bronze; 170 mm; facing right; the name ‘W. SICKERT’ running around the right edge], as do Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (No. 1973P40; further details forthcoming). This mercurial and influential artist seems therefore to have commissioned at least three likenesses from TSL – one more than Mabel Bent! note 3

There is a later, rectangular, relief (c. 35 cm x c. 25 cm) of Herbert Goodall (1857-1916), architect/artist member and third club Chairman, in the Chelsea Arts Club collection. note 4 The date is uncertain, presumably TSL cast it around the same time as the BM roundel (above). (An image of it can be seen at The Goodall Family of Artists.)

The Three Walker Roundels

Dorothea Mary Short (1890-1972) bequeathed her three TSL medallions (WAG 8458-60) to the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and they have inventory dates there of 1973. Dorothea inherited these bronzes from her mother, Esther Rosamund Short (née Barker, 1866-1925), who was left them in 1945 on the death of her husband, the celebrated printmaker and teacher Sir Francis (Frank) Job Short RA PPRE (1857-1945). Short and TSL were friends, and both members of the Art Workers’ Guild. TSL was elected Master in 1898 and Short in 1901. (Coincidentally, the two V&A TSL bronze reliefs referenced above, Sickert and Fennessy, were also donated by Dorothea Short.)

The three Walker TSL bronze roundels are:

WAG 8458 – (George) Percy Jacomb-Hood (1857-1929, c. 210 mm, c. 1881; Exh. RSBA 1887-8 (543)). Possibly one of the set of medallions of TSL’s friends, regularly referenced.

WAG 8459 – ‘Rose’ (Esther Rosamund Barker) (c. 200 mm, c. 1888, perhaps before her marriage to Frank Short in April 1889).

WAG 8460 – ‘Young woman with piled hair’ (perhaps Christabel Annie Cockerell (Lady Frampton, 1864-1951)), (c. 170 mm, date unknown), (previously mentioned above).

The sale of the contents of Claremont Court, Jersey, in September 2015, included another version of TSL’s Christabel Annie Cockerell relief. Lot 296 was enigmatically described as “A cast bronze portrait plaque probably first half 20th century, depicting a young man in profile, 7in. (17.5cm.) diameter”. It sold for £50.

For good measure, the Walker also has a marble bust by TSL of Frank Short (WAG 8461, 330 mm x 340 mm, date unknown), and a framed plaster relief of Esther Rosamund Short (framed: c. 670 mm x 530 mm, date unknown). Both it seems were also bequeathed by their daughter Dorothea Mary in 1972/3. Regrettably, none of the TSL pieces are currently on show at the Walker and it is to be hoped they will appear online in the future.

The above, taken together with the museum’s sculptures by TSL of ‘Alderman Edward Samuelson’ (WAG 4175, marble, c. 740 mm, 1885) and also ‘Mrs H.L. Johnston’ (WAG 4214, marble, c. 290 mm x 230 mm, 1881?), fittingly, make the Walker’s TSL collection the largest in the UK it would appear. (Pers. comm. and kind assistance (August 2024), Alex Patterson (WAG) and Whitney Kerr-Lewis (V&A).)

Miscellaneous references to TSL’s medallions and other portrait reliefs

A few “beautiful heads in relief”, by TSL at the New English Art Club, Dudley Gallery, Piccadilly (Winter show 1891)(reported in the Pall Mall Gazette, 16 Dec. 1891. (Possibly the set of TSL’s friends, regularly referenced.)

“The Fifth Exhibition of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers – In the summer of 1898 there was held at the Skating Rink, Knightsbridge, an exhibition of modern art which, from an artistic point of view, has never been surpassed in London… Mr. Stirling Lee (the energetic Honorary Secretary of the Society) is represented by two charming bronze medallions of children’s heads, and a marble bust of Mrs. T.B. Hilliard…” (The Connoisseur, International Exhibition Supplement, 1905, Vol. XI (Jan.-Apr.), 129ff.)

An untitled bronze medallion at the Manchester Art Gallery, The International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers Exhibition, 1905.

An untitled bronze medallion at the City of Bradford Corporation Art Gallery, Cartwright Memorial Hall Exhibition of The International Society of Sculptors, Painters, and Gravers, 1905.

Five untitled bronze medallions on show at the Leeds City Art Gallery Exhibition, 1909 (the set advertised at 10 guineas each).

An untitled bronze medallion on show at the ‘Exhibition of Fair Women’, Spring 1909 – International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London.

Sotheby’s, 16 March 1923, had a sale featuring the art collection of Nelson and Edith Dawson, including seven bronzes, “with rights of reproductions”, by “the late T. Stirling Lee”: Lot 179, “Head of a Girl; Lot 180, “Head of Mrs La Thangue” note 3 ; (Lot 181), “Medallions of Walter Sickert and [Herbert/Frederick] Goodall, the landscape painter” [the item presumably in the British Museum; note 3 Lot 182, “Three Figure Panels”.

It seems the painter Alfred William Rich (1856-1921) had in his collection a medallion by TSL which was eventually bequeathed to an unspecified museum by his wife Phillippa (Holliday) through the Art Fund between 1933 and 1935. It is referred to as a “Bronze Plaque of Girl’s Head”. It is impossible to know from research so far whether this roundel is one of those listed above. We may assume Rich and TSL were acquainted via the activities of the ‘International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers’, inter alia. Philippa in 1884 – might TSL have modelled a plaque of her for the painter?

Other busts

Perhaps in return for Wilson Steer’s portrait of him, or vice versa (see reference above), TSL does a bronze of Philip Wilson Steer (1860-1942), who died 1942. It was said to have been left to the Tate (Birmingham Daily Post, 17 July 1942), but is now in the Williamson Art Gallery & Museum, Birkenhead (along with a marble likeness of Dorothy (Seton), one of James McNeill Whistler’s models). It is not unreasonable to think that one of TSL’s earlier medallions also featured Wilson Steer, but there does not seem to be a direct reference to one.

TSL was an active member of the Art Workers’ Guild, and was elected Master in 1898. The Guild has a fine bronze bust of him (c. 1898), mallet and chisel in his hands, by Arthur George Walker (1861-1939). The Guild also displays TSL’s bronze (1900) of Sir Mervyn Macartney (1853-1932), commemorating Sir Marvyn’s year as Master, as well as TSL’s bust of John Brett (1831-1902), a British artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelites.

TSL attended Westminster School briefly (1870-1), his bust of Richard Busby (1606-1695), who served as headmaster for more than 55 years, was placed in the school for the bicentenary of Busby’s death in 1895. (TSL left abruptly to join the studio of sculptor John Birnie Philip as an apprentice.)

Other bronze plaques (non-portrait)

TSL produced several bronze relief plaques of religious and idealised themes throughout his career. An example is his ‘Mother and Child’, sold at auction in London in 2014.

Exhibitions and other works

The essential site for the works in general of TSL is to be found at “Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951”, edited online by the University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII. It is indispensable, beginning with a concise introduction to the artist. It features interactive sections on Works, Locations, Exhibitions, Meetings, Awards, many Lectures and other Events, Institutional and Business Connections, Personal and Professional Connections, Descriptions of Practice, Sources.

TSL’s works travelled around the world for exhibitions, i.e. a medallion (unspecified, item 927, cat. Page 45) appeared at the Christchurch Gallery, New Zealand, for the “New Zealand International Exhibition, 1906-7”.

There are several reference to TSL in ‘The Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society Catalogues’ for the 3rd exhibition in 1890 (at The New Gallery, 121 Regent Street, London) and the 11th in 1916 (the year of his death) (at The Royal Academy, Burlington House, London). For the 3rd exhibition TSL worked with A.G. Walker on a design by J.D. Sedding for an altar of alabaster, lapis-lazuli and metal (the plaster panels shown were intended to be repoussé metal). For the 1916 event, F.A. White lent three panels of saints carved by TSL – ‘St Ninian’, ‘St Bridget’, and ‘St Columba’. The material is unspecified. These were perhaps models of the representations of these saints produced by TSL for Westminster Cathedral (see below). This event was TSL’s last – he was to die suddenly in 1916, ineligible for the Great War, in progress now two years.

For the list of works displayed by TSL at the Royal Academy from 1878-1902, see Graves 1905: 21.

Other commissions

The Liverpool controversy

The following excerpt relates to the most significant commission of TSL’s career; it is taken from the University of Glasgow’s ‘History of Art and HATII’, online database 2011 – Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951. [This site presents unparalleled data on the working life of TSL.]

“[TSL’s] most important commission was the series of reliefs for the exterior of St George’s Hall, Liverpool. Lee was originally awarded the entire scheme of sculpture comprising twelve large reliefs and sixteen smaller panels (the latter on the upper parts of the building) through an open competition organised by Liverpool Council in 1882. However, due to a combination of high costs and the mixed reception that Lee’s first two relief panels received, only six relating to ‘The Progress of Justice’ (situated to the left of the portico) were completed under the original plans (1885-94).” (See, e.g., Dorment 1985: 24; Beattie 1983: 43 ff, including images)

The issue became a grand cause célèbre, with the artistic community generally rallying around TSL to get the contract honoured and completed. At a special meeting of the ‘National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry’ on 30 October 1889, a special Resolution, endorsed by hundreds of artists, sculptors, architects, etc., was passed to the effect: “That the Mayor and Corporation of Liverpool be approached with an expression of the hope that they will reconsider their decision to discontinue the decoration of St. George’s Hall by Mr. Stirling Lee and in accordance with his designs.” The Liverpool authorities were on the horns of a dilemma; they could not be seen to be spending City funds on designs that many considered, in many instances hypocritically, inappropriate, but at the same time a project much admired by influential voices within the artistic community. Ultimately a compromise was reached when “Mr. P.H. Rathbone liberally offered to defray the cost of making and setting up the remaining four panels, designed by Mr. T.S. Lee for St. George’s Hall.” (Transactions of the National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry 1889-91, Vol. 2, pp. xiv-xv)

For Morris (1997: 52) (who goes into the Liverpool debacle sensitively, “The whole Liverpool experience deeply demoralised the sculptor and his later work lacks the intensity and vision of the St George’s Hall reliefs. He was, however, well-educated, highly trained, sociable and articulate, and his importance lies in his ideas and influence rather than in his sculpture…”

It seems the designs TSL came up with for some carved stone panels to decorate some late-phase alterations to Leeds Town Hall, across the Pennines, were less controversial.

TSL’s bronze panels for the former Adelphi Bank, Liverpool

The sculptor’s bronze work includes the four relief panels on the great doors to the former Adelphi Bank building on the corner of Castle Street and Brunswick Street, Liverpool. (To appreciate the doors properly today you will need to wait until the coffee shop they open into is closed.) The overall design was by W.D. Caröe (1857-1938) and completed in 1892. Taking its theme from the bank’s name, Adelphi (‘brotherhood’), TSL’s panels – two per door, one above the other – were to represent ‘David and Jonathan’, ‘Castor and Pollux’, ‘Achilles and Patroclus’, and Roland and Oliver’. The panels were cast for TSL by his friend and Chelsea neighbour Conrad Bührer (1839-1929). Caröe’s design for the date on the doors is cryptic – on the left reading ‘1A8’ and on the right ‘9D2’ (i.e. AD 1892). For more information, see the Martin’s Bank archive and the Victorian Web. [Although this article focuses on TSL’s medallions, and Mabel Bent, readers might like to be reminded that Theodore Bent’s uncle, Sir John Bent (1793-1857), was Mayor of Liverpool in 1850/1.]

Prestigious commissions in marble

At the Royal Academy Exhibition (London) of 1911, TSL showed his marble bust of ‘Master Angus Vickers’ (cat. no.1820, p.106). Angus (1904-1990) was a young scion of the famous Vickers engineering family, being one of the three sons of Douglas Vickers (1861-1937), and this work was clearly a very prestigious commission for TSL; the boy was around six or seven years of age. Presumably the bust is still with the family and no image of this work seems to have been published. The photo shown here is a detail from a portrait of him painted when he was 21.

Edgar Wood

TSL took on several commissions for the busy ‘Arts & Crafts’ architect Edgar Wood (1860-1935). These included some ornate marble decorations for fireplaces at the Grade-1 listed Banney Royd House, Edgerton, Huddersfield (1901); sculpture and copper roof for the Clock Tower (listed Grade 2) in Lindley, Huddersfield (1900-2); and a small bronze statue, Woman and Child, at Long Street Methodist Church, Middleton, Greater Manchester (1903). (Click for a visit (Sept 2024) by TSL’s great, great nephew – by happenstance also Thomas Stirling Lee – to see the statue in the church.)

There is a suggestion that TSL provided the statue of the boy, now lost, for the extraordinary fountain centrepiece for Edgar Wood’s Jubilee Park, also in Middleton. It was opened in 1889 to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. Some commentators have likened the statue to TSL’s small model “The Music of the Wind”, now in the (stored) Sam Wilson Collection in Leeds (see above) (Jubilee Park Fountain, Middleton – Advice on Restoration, 2015: 24-5).

Silver work & Masonic jewels

TSL was an active Freemason: “A new lodge, for the convenience of professors of the arts of sculpture and painting, was consecrated on Tuesday [13 June 1899], at Freemasons’ Hall, London… The lodge is numbered 2751 on the roll of Grand Lodge of England.” TSL was appointed one of the officers. (The Freemason’s Chronicle, 17 June 1899, pp.287-9)

A spectacular and very rare centre-piece in silver for a table decoration for an unknown commission, designed and sculpted by Thomas Stirling Lee (c. 1904, dimensions n/a). Present collection unknown. (Illustrated in W.S. Sparrow 1904. The British home of today; a book of modern domestic architecture & the applied arts: 207, New York.)

A much-reproduced piece of sculpture by TSL is his spirited “Music of the Wind” of around 1907. A model in wax is now in Leeds, part of the Sam Wilson Collection (1851-1918); apparently a version in silver also exists, explaining the reference to it in this section of the works of TSL. It seems the entire Sam Wilson Collection (he was a local textile magnate) was placed in storage by the Leeds Art Gallery in 2009, and thus these sculptures by TSL must languish there (for a fine illustration, see Morris 1997: 53).

A Freemason, TSL was a founder of the ‘Arts Lodge’, designing splendid and unusual masonic jewels, i.e, ‘Past First Principal’s jewel for Public Schools Chapter, No. 2233 presented to E. Comp. Herbert F. Manisty, 1909’ and ‘Past First Principal’s jewel for Public Schools Chapter, No. 2233 presented to E. Comp. J. S. Granville Grenfell, 1917’, the latter presented after TSL’s death in 1916.

A brief obituary appeared in Ars Quatuor Coronatorum: being the transactions of the Lodge Quatuor Coronati (No. 2076, London, V.29, 1916, p.331): “Thomas Stirling Lee, a well known sculptor, of Chelsea, on the 28th June, 1916, in the sixtieth year of his age. Bro. Lee was a Past Master of the Old Westminsters’ Lodge No. 2233, and held the rank of Assistant Grand Superintendent of Works of England. He became a member of the Correspondence Circle in January, 1906.”

Monuments

TSL designed the memorial for fellow mason Henry Sadler (d. 1911), in New Southgate Cemetery, London. It was paid for by friends and lodge members. Just five years later, TSL was buried in the same cemetery.

Interiors

TSL designed and produced features for the Duveen residence at 22 Old Bond Street, London, and the interior of Palace Gate House, Kensington Gore: “The stranger… will not be tempted to hurry up the stairway where Mr. Stirling Lee and Mr. Frith together have thought out the modelling of the plaster ceiling and the arrangement of the balustrade.” And for the ‘museum room’, “Mr. Stirling Lee has here two little figures of Science and Literature standing out from the wall” (The International Studio, vol. 7, 1899: 99-100). The two little figures are untraced.

For H.A. Johnstone’s magnificent residence at 15 Stratton Street, London, TSL carved (c. 1904) from oak a series of “double-sided carved panels of entwined and realistically depicted children”, for a gallery balustrade. They were removed when the house underwent reconstruction. Provenance includes: Peter Marino Art Foundation, NY.

Church commissions

Westminster Cathedral, Ashley Place, London: “Chapel of St Andrew and the Scottish Saints, the gift of Lord Bute and the work of R. Weir Schultz 1910-14. Lean openwork screens of white metal by W. Bainbridge Reynolds; sculpture by Stirling Lee, stalls by Ernest Gimson (considered amongst his finest works) with kneelers by Sidney Barnsley, reliquary by Harold Stabler and altar cards by Graily Hewitt.”

St Mary’s, Stamford Parish, Lincolnshire: an “excellent bronze altar frontal in an Italian style by Stirling Lee”, as part of J.D. Seddings’ decorative scheme of the 1890s.

St James’, Heyshott, West Sussex: In Arthur Mee’s volume on Sussex in ‘The King’s England’ series (London 1937: 105), the author writes in relation to St James’ Heyshott: “The reredos has a plaster relief gilded and set in an old wood frame. It shows Christ in the centre with angels wrapped up in their wings on each side. It is the work of Stirling Lee, who lived here and died suddenly while doing it.” [This entry is now hard to support as the reredos referenced is not in situ. The Heyshott ‘Post Office Directory’ entry for 1911 lists TSL as residing, apparently, at Hoyle, just a few km s/w of Heyshott. The wonderful countryside made a welcome change from the Chelsea fogs and TSL would stroll and paint watercolours there – one entitled “Evening on Hoyle Common” was exhibited by him at a New English Art Club event.]

All Saints, Brockhampton, Herefordshire, UK. A unique Arts & Crafts church built around 1900 by the renowned architect/designer William Richard Lethaby (1857-1931). TSL was commissioned to carve the reredos.

St Paul’s Church, Four Elms, Kent, UK. After 1881, TSL helped assisted Henry Pegram with the carving of the reredos here (a plainly framed white marble relief of the Adoration of the Magi designed by W.R. Lethaby.

TSL was also on the team behind a scheme to redevelop the old Liverpool Cathedral but this was abandoned.

Bespoke carving

In 1891, TSL undertook a commission (Pall Mall Gazette, 4 Nov. 1891) to carve a figurehead for millionaire Wallace M. Johnstone’s (of 3 St James’s St, London SW) steam-yacht (possibly the The Lady Nell). This work, if complete, has not yet surfaced.

Three plaster panels – “reminding one forcibly of Blake at his best”

In the eclectic ‘Caxton Head Catalogue, No. 735’, of 6 January 1913, page 14, under ‘Sculpture’, three unusual TSL plaster panels were offered for sale by the great dealer James Tregaskis, at his house at the sign of the Caxton Head, 232, High Holborn, London, W.C. (“Every item has been collated with care, and is therefore guaranteed perfect unless the contrary is indicated.”)

“Original plaster panels in high relief, designed by Mr. Thomas Stirling Lee, and modelled by him. Magnificent examples of a very high order of mural decoration, by one of our foremost living sculptors, the boldness of their symbolic conception reminding one forcibly of Blake at his best.

“Cat. No. 992: ‘The children of the light holding their child in the rays of the sun.’ [Symbolizing the Light of Immortality]. 55 in. by 8 in. Bronzed. In massive oak and gold frame, glazed. 75 guineas.

“Cat. No. 993: ‘Pluto taking Proserpina down to the shades; with two side panels: The Metamorphosis of the Nymphs into Trees and Plants.’ [The centre panel symbolises the flowers hidden in the earth, the side panels the change of the seed into the tree and plant]. Each 8 in. by 13 in. In massive oak gold frames, glazed. The three, 36 guineas.

“Cat. No. 994: ‘Pluto and his Fire Horses; with side panels: Love taking her Child from the flames of Fire, and Truth testing her Child in the Fire’. [Symbolising the moral influences of Fire]. Each 8 in. by 16 in. In massive oak and gilt frames, glazed. The three, 36 guineas.”

Presumably these three mysterious panels, unfortunately not illustrated, were sold to a private collector, or returned to TSL. No other information on them seems to appear online. The reference to Blake is fascinating and seems to be unique. TSL’s poetic Liverpool panels could have stepped right from, inter alia, ‘Jerusalem’; and we dream again of Blake the sculptor…

Lost masterpieces

Three works by TSL in particular generated early interest in the young sculptor. All were exhibited at the Royal Academy and all are now unrecorded. Hopefully they are still being enjoyed within private collections, but they might also be lost. They do not appear to have featured in exhibitions or publications since the early 1900s. Perhaps still in TSL’s possession at his death they may well have passed to the family of his nephew, Gilbert Stirling Lee, of whom TSL was fond – his wife modelled for him.

Two of these works have already been referenced above, Adam and Eve finding the Dead Body of Abel, and Cain, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1881 (TSL was 24 or 25). Sadly, there appear to be no illustrations of them.

The Encyclopædia Britannica (1916, Vol. 24, p. 526), in its entry on modern British sculpture, opines: “[TSL’s] statue of ‘Cain’, extremely simple in conception, is a masterpiece of expression.” After the RA show of 1881, the marble appears again at the ‘International Exhibition’ held in Glasgow in 1888, labelled as “Cain” (item 1551, catalogue p. 91), and with an accompanying biblical quote: “And Cain said unto the Lord. My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou hast driven me out this day from the face of the earth.’ – Genesis iv.13, 14. There is a sale price included – £1000: an astonishing sum.

Unsurprisingly, in 1897 Cain was still in the sculptor’s collection and he lent it to the large “Victorian Era” event that year at London’s Earl’s Court. It is listed in the catalogue (item 468, p. 37) as “Cain.” “Mine iniquity is greater than I can bear” (based on Genesis 3:17). In 1908 it seems TSL showed it again (but perhaps as a plaster figure, item 1386, p. 130 of the catalogue) at the extensive ‘Franco-British Exhibition’ in London. The fratricide seems to have disappeared after that date…

The Dawn of Womanhood

It was in 1883, when TSL was in his early twenties, that the young sculptor exhibited his ‘Dawn of Womanhood’ – his other lost masterpiece – at the Royal Academy; a bravura piece very much reflecting the modern, fluid French style he had immersed himself in in Paris during his studies there (1880-1). Its reception was mixed from the start, with The Builder (19 May 1883, p.661) printing that “Mr. Stirling Lee’s contorted figure called by the magnificent title, ‘Dawn of Womanhood’, [is] one of the instances of titles far above the real achievement of the work. The recumbent figure, with head thrown back and agonised expression in the features, suggests rather the idea of ‘night-mare’.”

Edmund Gosse is more considered and measured in his (later) analysis when reviewing contemporary sculpture (1894):

“A step forward was taken in 1883 by Mr. T. Stirling Lee, in his ‘Dawn of Womanhood,’ a recumbent nude statue which attracted a great deal of somewhat bewildered attention in the [Royal Academy] Lecture Room. Never had anything of the kind been seen in England in which crude realism had been carried so far… [No] photograph does justice to this strange work, to which we look back with interest and amusement. The sculptor had, it is impossible to doubt, seen the Byblis changée en Source, by which Suchetet had, the preceding year, awakened a furore in Paris. Mr. Lee had perceived, with an artist’s instinct, how delightful and fresh that minute study of nature was. But he had missed the tact which so bold an experiment demanded. His ‘Dawn of Womanhood’ was like an absolute cast from the flesh. There was no selection of type, no striving after beauty of line; the figure was a literal copy of an ugly naked woman. Mr. Lee had not realised that, without style, Art does not exist. His experiment was interesting, and it distinctly marked a step in the progress of the school, but its influence was slight.” (‘The New Sculpture III, 1879-1894’, The Art Journal 1894, p.277)

In his all-embracing review of British sculpture, Bob Speel describes the subject, in his exploration of the theme of ‘dawn’, as “a young, awkward, almost gawky figure… a nude girlish figure in the act of awakening, mid stretch and with one hand against her hair”.

Four years after her Royal Academy debut, the (unsold) Dawn was exhibited by TSL at the 1887 ‘Royal Jubilee Exhibition’ in Manchester (item no. 942, p.324 in the catalogue), and then the following year at the 1888 ‘International Exhibition’, Glasgow (item no. 1634, p.94 , in the catalogue of the Fine Arts section), where she was offered for sale at £1000, easily over £50,000 today.

It seems to have been a decade later that she next made a spectacular appearance – at the 1897 ‘Victorian Era Exhibition’, Earl’s Court, London (page 36 of their catalogue, item 430). (Perhaps she found a buyer here, as a plaster copy only was on show at the 1901 ‘International Exhibition’, Glasgow – page 110 of its catalogue, item 80.)

And after 1901 Dawn of Womanhood seems to have vanished, with no reference to her in any collection today.

TSL the landscape artist

“The Fine Art Society has been exhibiting… landscapes by Mr. T. Stirling Lee. Mr. Lee, who is so well known as a sculptor, revealed a highly sympathetic treatment of landscape in his paintings (The international Studio 1897: 159). Perhaps these will appear one day.

TSL obituaries

“London – We regret to record the death of Mr. T. Stirling Lee, the well-known sculptor, who died suddenly at the end of June [1916]. The second son of Mr. John S. Lee, of Macclesfield, he was educated at Westminster School and then apprenticed to [John Birnie Philip], who was finishing the Albert Memorial. Mr. Lee studied at the same time at the Slade School, where he showed such aptitude for art that Mr. Armitage, R.A., advised his being sent to Paris, there being no school for sculpture in London at that time. Accordingly he next worked at the Petites Ecoles des Beaux Arts, and gained a first and a second medal during his first term. Subsequently he became a fellow-student with Alfred Gilbert in Professor Cavelier’s atelier, where he gained the R.A. gold medal and travelling scholarship, as well as the Composition Gold Medal of the Beaux Arts. At twenty-five Mr. Lee won the competition for the decoration of St. George’s Hall, Liverpool, but long delay on the part of the Corporation caused the young sculptor much early disappointment, and though he was allowed to finish part of his work, he died without seeing his life’s work completed. Two of his finest early works are Adam and Eve finding the Dead Body of Abel and Cain exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1881. He has done a good many portrait busts of notable people, amongst others Sir Frank Short’s daughter [see the ‘Walker Roundels’ section above] and Miss Kitty Shannon (1887-1974) [perhaps the subject of another unidentified medallion. Kitty, herself a talented illustrator, was the daughter of TSL’s acquaintance, and owner of some of his sculpture, Sir James Jebusa Shannon (1862-1923)]… He was one of the very few who carved direct in marble, from life. The later period of his art has been largely devoted to ecclesiastical work, an excellent example of which is his altar-piece in Westminster Cathedral, and he quite recently completed another altar-piece showing the Wise Men of the East, in which his love of symbolism found expression. As a sculptor Mr. Lee’s work was very individual. He was greatly attracted by the Early Greeks, and he was a born carver, with a strong sense of pattern.” (‘Studio-Talk’, The International Studio, vol. 59, no. 235, 1916: 175-6)

(For criticism of TSL’s carving from life, see Kineton Parkes 1931: 43.)

“The late Mr. Stirling Lee, sculptor – Many friends and lovers of art will deeply regret the sudden death of Mr. Thomas Stirling Lee, the well known sculptor. Mr. Stirling Lee was the sculptor of the reliefs at S. George’s Hall, Liverpool, which created some controversy at the time, but happily remain as Mr. Lee designed them, one of the finest monuments of his genius. This is indeed a satisfaction to those who remember the necessity for strenuously opposing any modification of the original design, for Mr. Lee was a sculptor of remarkable individuality and power, and had the distinction of his fellow-sculptors’ admiration in an unusual degree. Perhaps the greatest loser by his death will be the Church Crafts League, of which he was one of the original founders and a guiding spirit. The League was formed to bring the clergy into a better understanding of the arts, and into closer communication with artists. Much useful work has been done by it, mainly under Mr. Lee’s guidance. He was also the first secretary of the International Society of Artists.” (The Burlington Magazine For Connoisseurs, V. 29, 1916, p.264)

For other TSL obituaries, see, e.g., The Builder, 7 July 1916: 4 (‘We regret to announce the death, suddenly, on June 29, of Mr. Thomas Stirling Lee… ’); The Building News, No. 3209, 5 July 1916: 21 (‘Mr. Thomas Stirling Lee, sculptor, of the Vale Studio, Vale Avenue, Chelsea, fell unconscious in the arcade at South Kensington Station on Thursday [29 June 1916], and on being conveyed to St. George’s Hospital was found to be dead… The funeral took place yesterday (Tuesday [4 July 1916]) afternoon at New Southgate.’). Similar notices appeared, inter alia, in the Liverpool Echo (30 June 1916) and the Evening Mail (30 June 1916). It seems the solicitor acting for his estate was a member of the Jacomb Hood family (S Jacomb Hood, 27 Buckingham-gate, Westminster) (The London Gazette, 6 October 1916, p. 9694)

TSL’s addresses

Given variously as The Vale, 326 Kings Road, London; 35 Craven Street, Strand, London; Merton Villa Studios, Manresa Road, London. It seems his final London address (as well as his Chelsea studio) was 1 Campion Road, Putney (probably a modest Victorian villa, now demolished), and by 1916 he also had a base in the country, at Hoyle, near Selham, Sussex (The London Gazette, 6 October 1916, p. 9694).

The Lee family: A dynasty of surveyors, builders, architects, and artists.

John Swanwick Lee (1830-1883) = Janet Sterling (June 1851) (d. 1889) – their children: 1) John Stirling Lee (1852-1886) = Emma Charlotte Stevens – their child, Gilbert Stirling Lee (1878-1966); 2) Helena Lee (1854-1922); 3) Thomas Stirling Lee (1856-1916); 4) Philip Stirling Lee (1858-1909) = Mary Maud Single (b. 1858) – their children: a) Sarah Lee (b. 1868); Jane Lee (b. 1873); Philip (b. 1884); Eveline (b. 1887); Alfred (b. 1888); Lulu (b. 1890).

Obituary of TSL’s father

The Late Mr. J. Swanwick Lee

“We regret to have to announce the death of Mr. John Swanwick Lee, of Craven-street, the senior partner in the eminent firm of surveyors of that name. Although Mr. Lee has passed to his rest at the comparatively early age of 54, the extent of the works upon which he has been engaged would occupy too great a space for us to attempt any detailed notice of them. As a building surveyor his practice extended to all parts of the kingdom, and even to France. His association with the late Sir Gilbert Scott, and other leading architects for upwards of 30 years, brought him into connection with the largest and most important public and other works of his generation. It is not too much to say that more than 500 works bear his well-known signature on the estimates.

“Mr. Lee’s practice combined land and estate works with building, and, as an engineer, his works at Seaford Bay, Sussex, show a thoroughly practical way of protecting land endangered by the sea at moderate cost.

“In all mathematical questions Mr. Lee took a great interest, and contributed a paper on the Great Pyramid triangle, which may lay the foundation of important scientific results. Mr. Lee’s death will be mourned by a large circle of professional friends and acquaintances, and his loss to the immediate neighbourhood of his residence at Southgate will be greatly felt. Into every philanthropic or other movement for the benefit of the locality he threw himself with the utmost heartiness, and a great gloom has come over the neighbourhood by his death. Mr. Lee came from Macclesfield, and was a pupil of the late Mr. Charles Balam, surveyor. He leaves three sons, two of whom are partners in his firm, and his second son is Mr. Thomas Stirling Lee, sculptor.

“In all relations of life Mr. Lee was just and upright, and gained the respect of all with whom he came in contact. We extend our heartiest sympathy to his family in their great sorrow at the irreparable loss.” (The Building News, 5 Jan. 1883: 9)

We may assume that John Swanwick Lee provided well for all his children. His son, TSL, was able to live comfortably in Chelsea and in Sussex. The London Gazette of 6 October 1916 gives notice of his estate at the time of his death.

Another indicator of TSL’s private means was his willingness to invest in the works of fellow artists, many of them close friends. To the Spring 1903 Whitechapel Art Gallery Exhibition (London) TSL lent five pictures from his private collection: “Thames at Chelsea” by A. Holloway; “Yarmouth” by T. F. Goodall; “Sussex Downs” by James Charles; “Moonlight Walk” by J. S. Christie; and “Moonlight on Cairn” by James Paterson, A.R.S.A.

On his death in 1916, TSL’s large private collection passed through the hands of his executor, nephew, Gilbert Stirling Lee. Presumably the collection is now widely dispersed. TSL carved a marble head of GSL’s wife (1908), on show at ‘The Exhibition of Fair Women (International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London)’.

Footnotes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Mrs Rodney John Fennessy: Emily, née Selous (1837-1915). Fennessy (1837-1915) was manager of the River Plate Bank of London and Buenos Aires, residing at 37 Brunswick Square, London. Emily is known to have exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1873, 1882, and 1883 (Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904, Vol. 3, London, 1905, pp. 97-8; and see http://victorian-studies.net/gissing/newsletter-journal/journal-48-2.pdf).

We are grateful to Nadine Lees, Digital Co-ordinator (Digital Media & Rights), Birmingham Museums, for initial information on TSL Sickert medallion No. 1973P40. There is currently no photograph available and the item is presumably in store.

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

References & Further reading

Attwood, P. 1992. Artistic Circles. The Medal in Britain 1880-1918. London: British Museum.

Beattie, Susan 1983. New Sculpture. London: Yale University Press.

Dorment, Richard 1985. Alfred Gilbert. London: Yale University Press. [Containing several references to their friendship]

The Fitzwilliam Museum Syndicate’s Annual Report and list of Accessions made during the period 1 August 2006 – 31 July 2007. Cambridge, 2008: 18. [For the medallion of W. Sickert]

Gosse, Edmund = see ‘The New Sculpture’.

Graves, Algernon 1905. The Royal Academy of Arts; a complete dictionary of contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904, Vol. 5, p. 21, London: Graves. [For works displayed by TSL]

Historic England – Thomas Stirling Lee [For TSL’s church commissions]

Jezzard, A. 1999. The Sculptor Sir George Frampton, vol. 1. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds.

Jubilee Park Fountain, Middleton – Advice on Restoration, 2015: 24-5. The Edgar Wood & Middleton Townscape Heritage Initiative (THI) 2015.

Kineton Parkes, William 1921. Sculpture of to-day, Vol. 1, New York.

Kineton Parkes, William 1931. The Art Of Carved Sculpture, Vol. 1, London.

Macer-Wright, Philip 1940. Brangwyn: A Study of Genius at Close Quarters, London.

Matthews, Geoffrey 2002. Thomas Stirling Lee, the first Chairman, in The Chelsea Arts Club Yearbook 2022 (page numbers n/a). [The article includes a photo from the Reading Museum and Art Gallery in which TSL can be seen at the notorious ‘Rodin Dinner’ at the Café Royal, 15 May 1902.]

Mee, Arthur 1937. Sussex in the ‘The King’s England’ series: 105, London

Morris, Edward 1997. Thomas Stirling Lee, in Sculpture Journal, Vol.1, pp. 51-6. [This short, but important (and relatively recent) article is not to be missed; it happens to contain an extremely rare etching (c. 1890) of TSL by his friend G.P. Jacomb Hood. This work is currently in storage (internal object number H1989.203) at Brighton Museum, where it is described as showing “the sitter looking at the viewer, the head being sketched in detail. Lee is wearing a broad rimmed hat and he has a full beard and moustache. His shoulders and jacket are drawn with a few lines” (information kindly provided by Laurie Bassam, The Royal Pavilion & Museums Trust, August 2024). Morris’s article (not open access) is available from certain databases or Liverpool University Press.]

The New Sculpture, 1879-1894, in The Art Journal, New Series, 1894: 133 ff. [This extended essay by Edmund Gosse is perhaps the most oft-cited résumé and critique of the work and ideas of TSL in relation to his friends and contemporaries (mid 1990s). In the work cited here, the essay appears in three parts over a number of pages: 133-42, 199-203, 277-82, 306-11. The entire article is available free online, with several illustrations.

Ransome, Arthur 1907. Bohemia in London, London. [Aspects of artistic life in the late 19th century and the founding of the Chelsea Arts Club]

Roberts, Morley 1890. In Low Relief: A Bohemian Transcript: 19-20, 77-9, London.

Sparrow, W.S. 1904. The British home of today; a book of modern domestic architecture & the applied arts: 207-8. New York.

Speel, Bob. A website for British Sculpture & Church Monuments.

Spielmann, M.H. 1901. British Sculpture and Sculptors of Today: 66, London.

University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011 – Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951. [For considerable data on the working life of TSL]

The Victorian Web – Thomas Stirling Lee.

The Whistler 1991. Review of Artists and Bohemians by Tom Cross, in The Whistler (Autumn 1991: 12-14).

Wikipedia – Thomas Stirling Lee.

For a further selection of illustrated works by TSL, see Art UK – Thomas Stirling Lee.

A Final Word

“There are sculptors and sculptors in England, but few for whom their material becomes plastic before a great thought. It is possible to pass through a modern exhibition, and be unmoved by a single evidence of the feeling which shows that study and long labour have not been lost in the attainment of mechanical dexterity and power of construction, which are as nothing without spiritual insight and emotion. Yet there are men in the country who have this vision, and one of them is Stirling Lee of Manresa Road.” (Morely Roberts, The Scottish Art Review, vol. 2, 1889: 74)

To our knowledge there has never been an exhibition of the life and work of this ‘man of vision’- it is high time there was one.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article