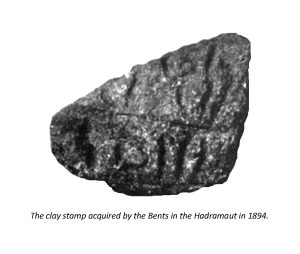

Did Mabel for some reason bury at Bethel, in the early 1900s, the clay stamp she and her husband acquired in the Hadramaut (Yemen) in 1894? Were there two identical stamps after all? And the missing squeeze? Where is this material now? A remark in the literature that the stamp might be in the Amman Archaeological Museum can be discounted (pers. comm. 2022).

Did Mabel for some reason bury at Bethel, in the early 1900s, the clay stamp she and her husband acquired in the Hadramaut (Yemen) in 1894? Were there two identical stamps after all? And the missing squeeze? Where is this material now? A remark in the literature that the stamp might be in the Amman Archaeological Museum can be discounted (pers. comm. 2022).

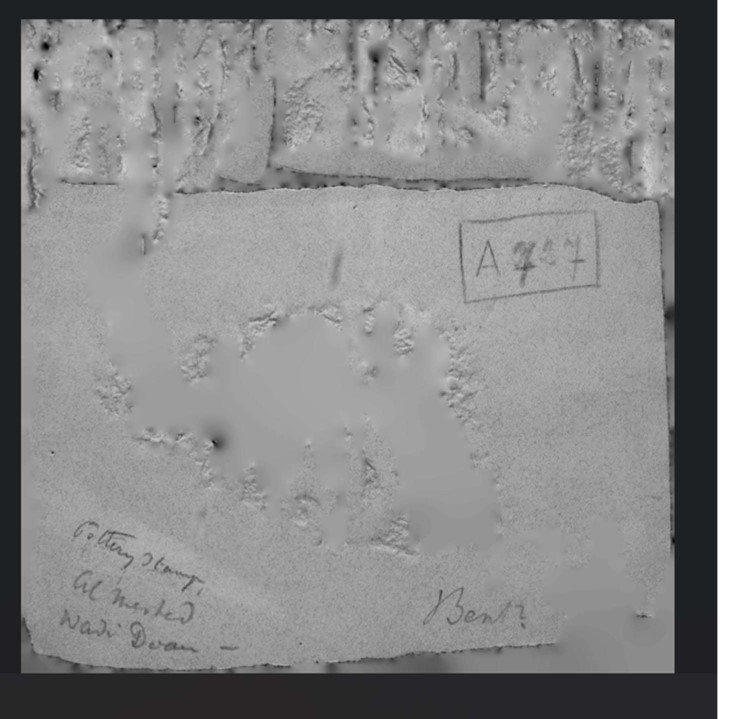

The actual paper ‘squeeze’ of the seal Theodore Bent sent to Eduard Glaser for identification has survived and is now held in the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW), Library, Archive and Collections: Information & Service, Vienna, within the Project IF2019/27; Glaser Virtual World – All About Glaser (GlaViWo), with the reference AT-OeAW-BA-3-27-A-A727. It represents, of course, unique documentary evidence.

Mabel Bent was a frequent traveller to Jerusalem and Palestine in the first decade of the 1900s (Theodore having died in 1897), and she soon began to demonstrate apparently irrational behaviour, i.e. taking sides in a romantic squabble between two British residents in Jerusalem, and making herself rather a nuisance to the authorities generally; on one occasion, now over 60, she rode off mysteriously and alone into the countryside of the southern Dead Sea, falling off her mount and breaking her leg; a convert to British Israelitism, she became involved in the committee of the ‘Garden Tomb’ (Jerusalem), and began her bizarre monograph on ‘Anglo‐Saxons from Palestine’.

In addition, and what might have been a decisive factor in terms of her stress, was that Mabel had to sit helpless on the sidelines and watch as Theodore’s ‘big idea’ – i.e. that proto‐Arab cultures had ventured as far south as modern Zimbabwe, building the great stone monuments there – was being disproved by contemporary researches, and that the twenty years of their travels and work together were ultimately undervalued by academics and the establishment.

If Mabel were sad and unhappy at Bethel, is it not easy to imagine her in a lonely moment in the early 1900s dropping a broken clay stamp from the Hadramaut into a hole and covering it up, muttering the while to her dead husband, with whom she had travelled such landscapes for so long, about how she had brought him, at last, to the end of one of the frankincense trails exploited by his trading proto‐Arabs? What could be more forgivable – not deliberate archaeological fraud but rather fondness and love? Who might not do the same thing? (And, as an afterthought, indeed, there were three seals the couple acquired in the Yemen – where did she drop the other two? Jerusalem, Hebron, Mizpah…?)

Read the full story in Mabel Bent and the Bethel Seal and send us your likes and dislikes! Mabel’s own on-the-spot ‘Chronicles‘ provide further details.

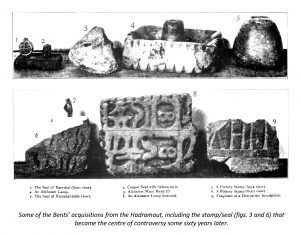

The photos show some of the Bents’ acquisitions from the Hadramaut, including the infamous ‘Bethel Seal’ (from the Bents’ ‘Southern Arabia‘ (1900), facing page 436).

The photos show some of the Bents’ acquisitions from the Hadramaut, including the infamous ‘Bethel Seal’ (from the Bents’ ‘Southern Arabia‘ (1900), facing page 436).

And did perhaps the same fate befall the mysterious ‘Seal of Yarsahal’ (a Hadramaut king?) (illustrated right) bought by the Bents in the region at the same time, and returned to London with them. It is illustrated in ‘Southern Arabia’ too, but has long since disappeared. Did Mabel also leave it somewhere in Palestine as a token to her dead husband? Who knows?

And did perhaps the same fate befall the mysterious ‘Seal of Yarsahal’ (a Hadramaut king?) (illustrated right) bought by the Bents in the region at the same time, and returned to London with them. It is illustrated in ‘Southern Arabia’ too, but has long since disappeared. Did Mabel also leave it somewhere in Palestine as a token to her dead husband? Who knows?

(For an interesting overview, see Dr Pieter Gert van der Veen’s article ‘Arabian Seals and Bullae Along the Trade Routes of Judah and Edom’, in Journal of Epigraphy & Rock Drawings 3 (2009) pp. 25-39. An updated version appeared as ‘Arabian and Arabizing Epigraphic Finds from the Iron Age Southern Levant’ (with François Bron), in J.M. Tebes (ed.) Unearthing The Wilderness: Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age (2014) pp. 203-226. Leuven: Peters).

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article