Mabel alone in Egypt: 19 January – 11 March 1898

The Bents returned from the Sudan via Athens in April 1896. Theodore has barely a year to live. During the summer of 1896 Theodore contributed various further articles on the Sudanese expedition before taking a cycling holiday with an old friend in East Anglia, calling in on Rider Haggard along the way. After further holidays in Ireland and the north of England, Theodore made ready to finalize their plans for the winter of 1896/7. He informs the cartographer H. R. Mill that he has been approached to explore the Horn of Africa once more:

‘My Dear Mill… Since I wrote to you last our plans for next winter are materially changed… I got a letter from the Governor of Zaila [Somalia] asking if I would undertake an expedition… this district apparently wants exploring both from geographical and political points of view and I think we shall attempt it. This will be a respectable basis on which to apply for a grant… We shall be back in London early in October when we shall meet…Yours very sincerely, J. Theodore Bent.’

But these plans came to nothing and by the end of October 1896 Theodore was thinking again of Southern Arabia. Over the summer of 1896 the couple decided to make a further (and final) attempt at explorations in the region, again in search of traces of the Sabaeans, and possibly reaching the western outer limits of the Hadramaut. The routes east and north-east of Aden would trace the ancient caravan/incense trails which once, according to Ptolemy’s map of the 2nd century AD, linked Aden with Shabwa in the Hadramaut. The well-worn thoroughfare led through Abyan to Bir Mighar, the territory being under the control of the Yafei and Fadli tribes, at the time relatively friendly to the British authorities.

Socotra, too, lay within Theodore’s field of interest. The island was long known from early references as a land of plenty, and Theodore would have a chance to see firsthand the spectacular resin trees that were sources of frankincense and myrrh renowned in antiquity. Further objectives would include a chance at some mapping, a basic study of the distinct language, and also to look for evidence of Christianity on the island. Marco Polo had mentioned the existence of Christians, and other authorities described a form of Christianity there as late as the 17th century. Socotra had the added benefit of being removed from the political disturbances of the Yemeni mainland.

Ultimately Theodore was ready to issue a syndicated press release of their next (his last) expedition, even though his itinerary was obviously not settled:

‘Mr. Theodore Bent will shortly leave England for Aden, where he proposes to stay a short time before finally deciding on his winter’s field of work. In all probability he will take the first opportunity which offers itself of going to the island of Sokotra, which has now for ten years been under British protection, and is politically attached to the Aden Government. Little is known of the interior of the island; and Mr. Bent proposes to spend the winter months in exploring it, and hunting for anything that may prove of interest from an archæological point of view. As usual, Mrs. Bent will accompany her husband, and the party will also include a young Oxford man who is anxious to do some work under Mr. Bent’s experienced guidance. These winter excursions of Mr. Bent’s have now become an annual institution, and always furnish forth material for an interesting volume.’

Unlike the Bents’ expedition to the Hadramaut of 1893-4, the party to Socotra and Aden was to be a modest affair, perhaps indicating a decline in interest by the London academic and scientific communities in Theodore’s commitment to Sabaean Southern Arabia. Travelling again with the Bents, for the last time, was their indispensable assistant from the Cycladic island of Anáfi, ‘Matthaios, the Greek who has travelled with us so many years’.

The Bents exhausted Socotra’s secrets within eight weeks. After some difficulty and expense they succeeded in hiring a small vessel to return to Aden, and, finding the neighbouring tribal families relatively peaceful, decided to explore east of Aden, perhaps even contemplating the north-east route towards the Hadrami interior once more. The Bents, with Manthaios, set out on 27 February 1897 for their last explorations together into the territories east of Aden. They were clearly weakened after their stay on Socotra and on March 16 Mabel records that ‘Theodore was in a raging fever so that I had to tell him I was now much better and had got quite strong, so I could take care of him.’ It was clear the expedition would have to be aborted and the arduous trek back to the coast, and onward boat journey to Aden, made as soon as possible. With great difficulty the stricken travellers were aided down to the coastal town of Shuqra for the 100km return sail to Aden, and by 26 March were both in hospital there.

After their stay in hospital in Aden the couple said goodbye to Manthaios (who had dysentery and was also hospitalized) for the last time and set sail for England, via Marseilles. During the return journey Theodore had a relapse, developing pneumonia on top of malaria. With the last of his strength they reached their London home on 1 May. Despite the attentions of Mabel (and her sister Ethel), the resident doctor and two nurses, Theodore did not recover, succumbing just a few days after their final trip on 5 May 1897.

If Mabel’s final travel Chronicle in the company of Theodore was one of her most readable, then her first (and last) solo effort is a wistful pendant; understandable enough, she has been a widow for eight months and her life a tangle of black crepe.

Her husband’s death meant that Mabel’s 20-year routine of winter expeditions followed by a pleasant summer round of English and Irish visits, as Theodore wrote-up and lectured on the previous season’s explorations came to an abrupt halt, and she was faced, aged only fifty and driven by that need to be somewhere else, with embarking on the next phase of her travels, even if accompanied, alone.

No doubt encouraged by her relatives, Mabel elected to put together for herself a ‘Cook’s Tour’ to Egypt and the Nile. But, often a mistake to revisit sites of earlier happiness, Mabel’s Egyptian pages that follow here in this final chapter, echo a series of muted contrasts, sighs, and signs of near depression. That image of a confident, smiling Mabel climbing the Giza Pyramids on her birthday in 1885 is the one that reappears as she groans ‘so sadly to Mr. Aulich’ of the Cairo Hôtel d’Angleterre, or rides ‘alone and unknown and unknowing’ around the great sites.

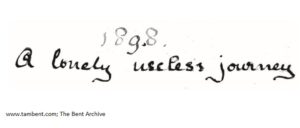

The heading of her final Chronicle reads ‘A lonely useless journey’, suggesting that even if she were not recalling it with bitterness at some later point, then she was well into the trip, alone in her hotel room, when she took out her notebook and began to write. Too many pages in it are taken up with an account of Joseph and his polychrome coat: there is nothing (thankfully) like it of such length in all her diaries. As well as hoping that it might no doubt interest her sisters and relatives in some way, Mabel presumably was practising her descriptive skills – Southern Arabia was soon to be written. She may even have been considering that she could in future write for British periodicals. She never did.

Although her (possible) trip along the Nile in 1889/1900 may have seen her back to her old self, the downbeat tone of the Chronicle continues on (Friday) 11 March 1898 when Mabel leaves Egypt for Athens, arriving there on 13 March. Her diary peters out after four days. Her last chronicled words, after fifteen years of note-taking and with her dead husband clear in her thoughts, are extremely touching in their understatement: ‘Of course I have not neglected the antiquities either’.

Theodore would be approving somewhere.