Dr Marielle Risse now lives in Cambridge, MA. She taught cultural studies, literature and pedagogy for 21 years on the Arabian Peninsula at the American University of Sharjah (UAE), the University of Sharjah-Woman’s (UAE) and Dhofar University (Oman). Her research areas are Arabian Peninsula cultures and intercultural communication. Her previous books are Community and Autonomy in Southern Oman (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), Foodways in Southern Oman (Routledge, 2021) and Houseways in Southern Oman (Routledge, 2023). Her most recent book is Researching and Working on the Arabian Peninsula: Creating Effective Interactions (2025, Palgrave Macmillan).

Dr Marielle Risse now lives in Cambridge, MA. She taught cultural studies, literature and pedagogy for 21 years on the Arabian Peninsula at the American University of Sharjah (UAE), the University of Sharjah-Woman’s (UAE) and Dhofar University (Oman). Her research areas are Arabian Peninsula cultures and intercultural communication. Her previous books are Community and Autonomy in Southern Oman (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), Foodways in Southern Oman (Routledge, 2021) and Houseways in Southern Oman (Routledge, 2023). Her most recent book is Researching and Working on the Arabian Peninsula: Creating Effective Interactions (2025, Palgrave Macmillan).

Theodore and Mabel Bent journeyed to Oman in the winter of 1894/5, and, having seen many references to the explorers in Marielle’s work, we asked her if she would care to write something for us, of her choice, weaving the Bents into the landscape she loves…

Cite from this article, please, as: Marielle Risse, ‘Ya Mabel’ and the Duchess: A Victorian but Modern, Female Traveller and a Modern but Victorian, Female Traveller in Southern Oman. An article in The Bent Archive website, August 2025 [http://tambent.com/2025/08/07/ya-mabel-and-the-duchess-by-marielle-risse/]

‘Ya Mabel’ and the Duchess: A Victorian but Modern, Female Traveller and a Modern but Victorian, Female Traveller in Southern Oman

By Marielle Risse, August 2025

Abstract

Has travel writing moved with the times, shedding racism, colonialism, ‘othering,’ and metro-centric points of view? What are the conditions in which ‘imagination and humility necessary to climb into the head of people who live by a very different set of assumptions’ is created? Later travellers to southern Oman have seen and reported only what was most unusual, most foreign and more recent books about the Dhofar region show less understanding of the culture than articles and books written in the 1800s. We will discuss two specific examples of this odd juxtaposition: a Victorian, female traveller who is more accurate about Dhofaris than a modern, female traveller.

Keywords: Dhofar, Mabel Bent, Oman, Qara Mountains, Theodore Bent, travel writing; Jan Morris, Suzanna St. Albans, Wilfred Thesiger

Introduction

My starting question for this research is: has travel writing moved with the times, shedding racism, colonialism, ‘othering,’ and metro-centric points of view? Thinking specifically about southern Arabia, why would Thesiger, now described as ‘a fond old blimp in cavalry-twills’ write about inhabitants of the southern Dhofar region with understanding and respect while writers from the late 20th and early 21st centuries stay stuck in the ‘exoticizing’ mode? note 1

Thesiger’s Arabian Sands is widely acclaimed as a great travel book; it is also an accurate travel book. note 2 He not only wrote what he observed, he wrote the explanations for the actions and attitudes he observed. He had the rare advantage of time, but even if his work is set aside, the earlier explorers/surveyors of the Dhofar had, within the blinkers of their ‘imperial gaze’, an ability to observe and report accurately. note 3

Many later travellers to southern Oman saw and reported only what was most unusual, most foreign. These more recent books about the Dhofar region show less understanding of the culture than articles and books written in the 1800s. I will discuss two specific examples of this odd juxtaposition: a Victorian, female traveller who is more accurate about Dhofaris than a modern, female traveller.

Theodore (1852-1897) and Mabel (1847-1929) Bent, quintessential Victorians, explored the coast and the mountains of southern Oman in 1894. A few years later, Theodore having died four days after their return to England from Aden in 1897, an account of their travels in the wider region feature in Southern Arabia (1900), compiled by Mabel. note 4 With reference to Oman, although there are plenty of acidic comments [‘Merbat [Mirbat] is uncongenial’ with ‘no points of interest’], Mabel also includes careful documentation of the tribespeople living in the Qara Mountains (232). She was not pleased that the Qara men addressed her only as ‘Ya Mabel’ instead of ‘Mrs. Bent’ but she was capable of insights such as ‘Travelers like ourselves must be a great nuisance drinking up the scanty supply of water’.

I will compare her work to another Western woman who has written about the same area, including the Qara mountains, the Duchess of St. Albans, who was, surprisingly, less perceptive. In Where Time Stood Still: A Portrait of Oman (1980) St. Albans writes of the ‘primitive’ tribespeople who ‘have never worked with their hands’. How would ‘primitive’ people living in caves and herding flocks have survived if they had ‘never worked with their hands’?

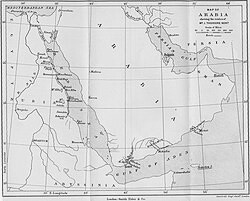

The Bents

Theodore and Mabel had already explored in Italy, Greece, Bahrain, South Africa, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Yemen when they arrived in Oman. Their trip to Dhofar began when they left ‘Maskat’ (Muscat) 17 December 1894 and travelled by ship south along the coast, arriving in Mirbat on 20 December. After travelling along the coast and up into the mountains, they left the Dhofar region from Al Hafa (part of modern-day Salalah) on 23 January 1894. I believe they are the first Westerners to visit the Dhofar mountains to write a description of it.

Although the Bents were not in the employ of the British government, they were quintessential Victorian-age travellers who, in their writing, specifically support British imperialism in their Southern Arabia (1900/2005). The book, as mentioned above, written by Mabel after Theodore died soon after returning to England from Yemen in 1897, viewed all landscapes through the perspective of how the land might be useful to the Empire:

‘If this tract of country comes into the hands of a civilizing nation, it will be capable of great and useful development… and a health resort for the inhabitants [i.e. British inhabitants] of the burnt-up centres of Arabian commerce, Aden and Maskat (274).

Southern Arabia is a book with plenty of spleen – it’s impossible to say how much is caused by Mabel Bent’s mourning for her dead spouse or her natural disposition. In either case, it is amusing to come across her acid opinions: Mirbat has a ‘malarious-looking swamp’ and ‘Our boat was one of the dirtiest I have ever travelled on’ (232). She is clearly a forerunner to the Theroux/Naipaul/Granta/ ‘I hate the natives’ school of travel writing: ‘The Bedouin are rather clever at impromptu verses, and when we were in Wadi Ser they made night hideous by dancing in our camp’; ‘There is no law, order, authority, honor, honesty, or hospitality, and as to the people, I can only describe them as hateful and hating each other’; ‘it appears that a very wicked branch of the Hamoumi tribe hold a portion of this valley’; and she refers to one of the men she travelled with as ‘that horrid little Saleh Hassan’ (128, 175, 177, 217).

The Qara men she travelled with always addressed her, to her anger, only as ‘Mabel’ (258), with the local prefix when calling a person ‘ya’ – as in ‘Ya Mabel!’ They informed the Bents that ‘they did not wish us to give them orders of any kind as they were sheikhs’ and ‘We are gentlemen’ (258, 266). The mountain people of Dhofar, Mabel Bent writes, are:

‘… endowed with a spirit of independence which makes him resent the slightest approach to legal supervision… They would not march longer than they liked; they would only take us where they wished… and if we asked them not to sing at night and disturb our rest, they always set to work with greater vigour (248).

But she always includes a fair amount of real information, taking the time, for example, to explain how indigo is used to dye clothes (145). She also kindly gives hints to future travellers, i.e. warning future geologists that they must tell the camel men ahead of time they will carry rocks and that anthropologists should investigate the religion of the mountains (212, 261). She describes the scenery with careful attention to plants, rock formations, distances, etc. (e.g. Wadi Ghersid, 256; Wadi Nahast, 265) and, noticing that the language spoken in the ‘Gara’ [Qara] mountains was not a dialect, she includes a few words (275). Some of her information is still current. She mentions, for example, that oaths ‘to divorce a favourite wife, are really good’ (180) and the technique of cooking on stones (250), which I have seen practised several times.

The Bents eventually stop struggling to control and ‘we gave up any attempt to guide our own footsteps, but left ourselves entirely in his [Sheik Sehel] hands, to take us whether he would and spend as long about it as he liked’ (257).

Her summation is typical of British Victorian-era travellers: ‘We had discovered a real Paradise in the wilderness, which will be a rich prize for the civilized nation which is enterprising enough to appropriate it’ (276). Within the limited, imperialistic, point-of-view, a reader gets a clear sense of the place and the people. The Bents have a diamond-hard sense of self self-assurance, but they are able to describe accurately and write in a way which effectively gives you the information you need: as you understand the author’s prejudices, you can understand the places and people described and you can thus make your own judgment about both.

Morris

It is rather a surprise, after the gradually lowering racist/condescending tone seen in the arc from the Bents through Thesiger, to read Jan Morris’ Sultan in Oman (2008/1957) a smug, complacent, and judgmental book. note 5 She begins by widely overstating her achievement, declaring that she undertook the ‘… last classic journeys of the Arabian peninsula’, as if being driven in a jeep from Salalah to Muscat in 1956 was on par with Dougherty or Philby (1). To drive home the (moribund) English tradition, she notes that ‘Curzon and Gertrude Bell rose with us approvingly’ (2).

The descriptions illuminate more about Morris’ travels than Oman, i.e. Risut is like ‘… a bay in Cornwall or northern California’ (20); ‘The deeper we penetrated into these Qara foothills, the more lifeless and unearthly the country seemed… It was like an empty Lebanon’; the ‘abyss of Dahaq’ is compared to ‘Boulder or Grand Coulee’; and the Qara mountains ‘felt like England without the churches, or Kentucky without the white palings’ (27, 27, 38). A small lake is ‘“Better than the Backs”, said my companion, “not so many undergraduates”’, which only makes sense if the reader knows this is a term referring to the place where several Cambridge colleges back onto the River Cam (30).

The people have ‘obscure rituals, taboos, and prejudices’ (31). In keeping with the general tone of relegating the inhabitants to prehistoric times, there is no mention of guns. The people ‘hurl in the general direction of their neighbours the heavy throwing sticks (less scientific than boomerangs) with which they were sometimes quaintly armed’ (40). It is clear even in Thesiger’s texts that the men of this region had access to and knowledge of guns. In fact, the cover of one edition is one of Thesiger’s photos showing Bin Ghabaisha holding a rifle.

The Dhofar War

I need to segue to briefly describe the war, from 1965-1975, in order to make my critique of St. Albans. The Dhofar War began as a result of widespread dissatisfaction with the rule of Said bin Taimur, which has been ‘characterized as a desperate attempt to keep the Fifteenth century from being contaminated by the Twentieth’. note 6

Various groups of Dhofaris, primarily from the mountains, and angry at the lack of schools, clinics, electricity, etc., began to attack Oman’s small military forces, the Sultan’s Armed Forces (SAF). These groups coalesced into the Dhofar Liberation Front in 1964, which was then re-named, in 1968, People’s Front for the Liberation of Oman and the Arabian Gulf, and ‘a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary program was adopted for the rebellion’. note 7 Its goals included: ‘the liberation of slaves’; ‘the equality of women’ (which included the elimination of polygamy); ‘demolition of the tribal system’; and ‘the unity of all revolutionary forces in the Gulf’. note 8

The SAF did not have enough men or equipment to cope with the insurgency, but the Sultan refused to spend money for the army, nor did he show any understanding or mercy towards the rebels’ demands. The result was that by 1970, the rebels controlled almost all of the Dhofar region. In the same year, in a bloodless coup d’etat, Sultan Qaboos took over control of his father’s government and immediately started a two-front counterattack. He increased the military presence and initiated a hearts and minds campaign to assure the rebels that he intended to meet their demands for modernization.

Soldiers who left the rebels were treated as ‘returning sons’; they were interviewed and immediately released, not jailed. note 9 Sultan Qaboos also ‘emphasized that the past practices of indiscriminate reprisals against civilians on the Jebel had to end.’ note 10

The military who fought the rebels held them in respect as fighters; the enemy was ‘extremely good at seizing the initiative and had a wonderful eye for ground… once outflanked, they tended to melt away’. note 11 Their praise of the rebels is all the clearer when comparing the rebels to fighters from other countries who fought for the Sultan; Iranian and Jordanian soldiers are not accorded the same respect.

As firqat (civil militia) units were created, British soldiers then had the experience of fighting with men who had previously fought with the rebels. Although Jeapes, who wrote one of the first books about the war, often shows his impatience with Dhofaris, he and the other foreign writers have an overall positive impression. Gardiner writes: ‘Omanis were wonderful people to live with. They were superbly honest… They were generous to a fault and… they didn’t take themselves too seriously… [they] wished to be at peace with any man who was ready to be at peace with them.’ note 12

St. Albans

St. Albans’ travel book recounts her extended visit to Oman in the late 1970s. She was clearly no average tourist; her first ‘thank you’ in her Acknowledgements section is to Brigadier Peter Thwaites. The second is ‘The Sultan’s Armed Forces provided transport where I wanted to go’ (ix). Most of the other people mentioned are also British and military. She has done some reading about the history of Oman, but her opinions reflect no ability to understand the reality of the people. One example, of many, is her assertion that:

‘There is a company in England which manufactures florescent braces to make camels visible in the dark, but no Bedu in his right mind will go to the expense and trouble of importing this equipment for his animals. It is very much to his advantage anyway to get them killed on the roads, as the compensation for such a casualty is £500 each.’ (146)

How would desert-dwellers in Oman in the late 1970s have access to information about companies in England? How would they have access to things such as post-office boxes and credit cards to enable such a transaction? It is not to a camel owner’s ‘advantage’ to have his livestock killed by a car, the meat cannot be eaten, and as camels wander far afield, the owner may never know which vehicle killed the camel, not to mention the fact that camel owners grow attached to their animals.

When she arrives in Salalah, her statements become quite difficult to understand. She states that there are ‘nine illiterate tribes of primitive aborigines in the Qara [Mountains]’ (152). note 13 These ‘primitive aborigines’ had just waged a ten-year war with the Omani government in which they had close contact with not only the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, but Russia, China, Cuba, and various Arab countries.

Musallim bin Nafl, the first leader of this revolution, is dismissed by the Duchess as ‘a useless loafer’ and a ‘shiftless, bitter, dissatisfied layabout’, but when she visits mountain villages she is appalled at the conditions (155, 156).

She never connects the revolution encouraged by Musallim and the desperate poverty endured by his people. She writes that the ‘entire population of the Jebel were forced to co-operate’ in the war (157), without understanding that the disease and lack of food she sees in the late 1970s would have been worse in the late 1960s. The difficulties of daily life she herself witnessed encouraged the mountain people to fight against their government – which denied them the basic amenities of modern life such as schools and electricity. note 14

In reading her autobiography Mango and Mimosa (2000), which recounts her work for the British military in World War Two, you might explain that her apathy towards the mountain fighters was generated (maybe sub-consciously) because they fought the British – but even the British who fought the Dhofaris were more realistic/understanding of their situation.

St. Albans describes the Bait Kathiri tribe as ‘nimble as goats’ and says that ‘like our own distant ancestors, they frequently paint themselves blue all over’ (168). Comparing men to animals is grossly insulting in Dhofar and the men do not paint themselves blue. Men and women traditionally wore indigo-dyed fabric which turned the skin blue, an important difference.

These small mistakes create a vision of an ancient, primitive people which erases the reality of the Dhofar region in the late 1970s. St. Albans only carefully describes the life of a small percentage of the inhabitants, living in caves and rough dwellings in the mountains. She discusses ‘witch doctors’ but not the many mosques or daily religious practices of Dhofaris (154). In Salalah at this time there was an airport, Holiday Inn, ‘shops and offices and ultra-modern television centre’, and a hospital (180), but she never shows Omanis interacting in/working in these modern surroundings. The ‘comfortable seaside bungalow’ she stays in is owned by British ex-pats, who are described, but when visiting the ‘model farm’, there is no reference to Omanis who work there (163, 164).

Discussion

In the modern books, the emphasis is firmly placed on the ‘exotic’; where both the Bents and Haines (1845) are able to discern that the people’s ‘skins are discoloured by the dye from their dress, which is composed of blue cotton’ (112), St. Albans sees people who paint themselves.

Evelyn Waugh wrote, ‘It was fun thirty-five years ago to travel far and in great discomfort to meet people whose entire conception of life and manner of expression were alien. Now one has only to leave one’s gate. All fates are worse than death.’ note 15 I think that ‘leaving one’s gate’ is no longer ‘alien’ enough – modern travel writers have an up-hill battle trying to show that they are doing/discovering something new, hence the emphasis on the unusual.

Mabel Bent and her husband were looking for land that would be of benefit for their country; St. Albans was looking for bizarre stories to tell. It is striking how the more recent writers show less understanding and less respect than British writers for the imperialistic era, given the modern emphasis on equality and multi-cultural education. note 16 Gardiner writes that:

‘The patience and tolerance to live harmoniously in an unfamiliar culture; the fortitude to be content with less than comfortable circumstances for prolonged periods; an understanding of and sympathy with a foreign history and religion; a willingness to learn a new language; the flexibility, imagination and humility necessary to climb into the head of people who live by a very different set of assumptions; none of these are found automatically in our modern developed Euro-Atlantic culture.’ note 17

The question remains: What are the conditions in which ‘imagination and humility necessary to climb into the head of people who live by a very different set of assumptions’ is created?

References

Belanger, Kelly 1997. ‘James Theodore Bent and Mabel Virginia Anna Bent’. British Travel Writers: 1876-1909: 31-40. Detroit: Gale Research.

Bent, James Theodore 1895. ‘Exploration of the Frankincense Country, Southern Arabia’. The Geographical Journal 6.2: 109-33.

Bent, James Thedore and Mabel Bent 2005 [1900]. Southern Arabia. London: Elibron.

Bent, Mabel 2010. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Volume III: Deserts of Vast Eternity, Southern Arabia and Persia. Gerald Brisch (ed.). Oxford: Archaeopress.

Haines, Stafford 1845. ‘Memoir of the South and East Coasts of Arabia: Part II’. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 15: 104-160.

Morris, Jan 2008 [1957]. Sultan in Oman. London: Eland.

St. Albans, Suzanne (Duchess) 2000. Mango and Mimosa. London: Virago.

— 1980. Where Time Stood Still: A Portrait of Oman. London: Quartet Books Ltd.

Thesiger, Wilfred 1991 [1959]. Arabian Sands. New York: Penguin.

— 1950. ‘The Badu of Southern Arabia’. Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society 37: 53-61.

— 1950. ‘Desert Borderlands of Oman’. Geographical Journal 116: 137-171.

— 1949. ‘A Further Journey across the Empty Quarter’. Geographical Journal 113: 21-46.

— 1948. ‘Across the Empty Quarter’. Geographical Journal 111: 1-21.

— 1946. ‘A New Journey in Southern Arabia’. Geographical Journal 108: 129-145.

Endnotes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

Return from Note 8

Return from Note 9

Return from Note 10

Return from Note 11

Return from Note 12

Return from Note 13

This attitude is not shared by any of the soldiers who fought in the war, or other researchers. The alternate view can be seen in Trabulsi: ‘He [Sultan Said] introduced oil companies into the Sultanate and he wanted to obliterate any social, political, or cultural effect they might incur. Furthermore, he wanted to monopolize the oil revenue and retain the old economic basis of his system: extortion of the economic surplus through taxation and levies. He was determined not to share a penny with a hungry, undernourished and unemployed population what was discovering, through emigration, the fabulous economic possibilities of the oil economy.’ ‘The Liberation of Dhofar’, 8.

Return from Note 14

Return from Note 15

Return from Note 16

Return from Note 17

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article