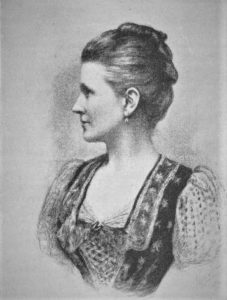

It’s taken far too long, but at last Mabel has joined Theodore on Wikipedia!

Many thanks to the Wikipedia mentors!

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

It’s taken far too long, but at last Mabel has joined Theodore on Wikipedia!

Many thanks to the Wikipedia mentors!

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article Very good to know that Mabel’s three grand Irish homes are still in good hands!

Very good to know that Mabel’s three grand Irish homes are still in good hands!

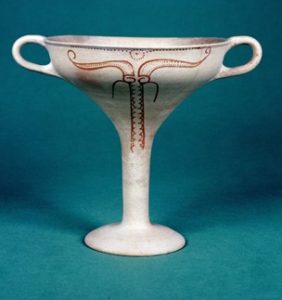

Home 1: Beauparc, Co. Meath – On 28 January 1847, Mabel Virginia Anna Hall-Dare (d. 1929) was born in Beauparc House to Mrs Frances Anna Catherine Hall-Dare (c. 1819-1862) and Robert Westley Hall-Dare (1817-1866). Frances was the daughter of Gustavus Lambart, of Beauparc, and his wife Anna (née Stevenson). Retaining all her life an affection for the house, lording it over the Boyne, the mansion was built in the 1750s for the Lambart family, who retained it until the last Lambart, Sir Oliver, ‘a wonderful if somewhat retiring and eccentric individual’, died in 1986, leaving it, to the new owner’s ‘total and utter astonishment’, to Henry Conyngham, 8th Marquess Conyngham (born 25 May 1951) – dubbed (Wikipedia): ‘…. the rock and roll aristocrat or the rock and roll peer owing to the very successful series of rock concerts he has hosted since 1981, held in the natural amphitheatre in the grounds of Slane Castle [Slane falls within the estate, a few miles away across the river]… These concerts have included performances by The Rolling Stones, Thin Lizzy, Queen, U2, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, Guns N’ Roses, Oasis and Madonna.’ Not too sure how Mabel would have taken to ‘Start me up’ rocking in over the Boyne, but who knows?

See also this entry on Beauparc in Irish Historic Houses (accessed 28/01/2022)

Home 2: Temple House, Co. Sligo. You can’t stay with your in-laws forever, perhaps, and the Hall-Dares were soon looking for an estate of their own; Robert’s father being a very wealthy Essex landowner and Demerara sugar-plantation owner. In the late 1850s, therefore, the growing family decamped from Beauparc, purchasing Temple House from the Percevals, at a discount, the latter in some financial discomfort. It was not to remain with the Hall-Dares for long, however: in 1861 Mabel’s father assaulted his gamekeeper’s wife and spent a month in Sligo gaol for his crime. Disgraced, he resold the house and lands to the Percevals – and delighted were one and all to see them back, for the Hall-Dares: ‘had a very different view on their duties and became notorious for evicting many families.’ Still magnificent and happily in Perceval hands, the fine house is now a luxury hotel – you can relax in grand style where Mabel spent her early childhood. Looking at the wonderful main stairs from the hall, it is easy to imagine the Hall-Dare children playing happily along them…

Home 3: Newtownbarry, Co. Wexford. Robert, never down for long, moved his wife and several children 230 km across country down to Co. Wexford, and the village of Newtownbarry (now Bunclody). ‘For its size,’ boasts the 1885 Wexford County Guide and Directory, ‘there is no town in the County Wexford to compare with Newtownbarry. As a business place, its record is first-rank, and in scenic attractions it stands in the front rank. It is situated on the right bank of the Slaney, bordering the County Carlow, seven miles Irish from Ferns, the nearest railway station, nine miles English from Shillelagh, in the County Wicklow; ten miles Irish from Enniscorthy and sixteen miles Irish from Gorey. Originally it was called Bunclody. Clody, in Irish, signifies a mountain torrent, and bun is butt…’ [Bassett’s Wexford County Guide and Directory: a book for manufacturers, merchants, traders, land-owners, farmers, tourists, anglers, and sportsmen generally (George Henry Bassett; Dublin: Sealy, Bryers, and Walker, 1885, p.343).

Hall-Dare bought the rather modest house in the estate grounds from the Maxwells in 1861/2, and promptly set about enlarging it, although he died in 1866 (as an in-patient in the up-scale asylum for distressed gentry, Ticehurst House Hospital, East Sussex), never seeing its completion. Three other deaths must also have hit the young Mabel very hard – that of Frances, her mother in 1866, from what seems to have been ovarian cancer, the apparent suicide of her younger brother Charles, a single pistol-shot, just the other side of Worcester railway station, on 31 January 1876 (three days after Mabel’s birthday), and the death in Rome (from typhoid) of her elder brother Robert a few months later, on 18 March 1876. Despite these tragedies, Mabel remained at Newtownbarry until her marriage to Theodore Bent in 1877, and to them one might look for Mabel’s need to travel, to be somewhere else as soon as she possibly could, marriage her ticket. Solid-looking Newtownbarry House, in conversation ever with the trouty, brown Slaney just below it, was designed by the well-known Belfast architect Sir Charles Lanyon between 1863-69; it is still in family hands, Mabel’s great-niece being the current owner.

Before we leave the amiable village, let’s take a stroll with George Henry Bassett: ‘Newtownbarry has many beautiful walks, but the one which is most favoured by the people is that leading off the Market Square over the bridge. Steep steps connect the public road with the river-path. Following this a few hundred feet a scene of rare loveliness is presented. Rich pastures extend far into the distance, skirted by a hill, which rises precipitously, a mass of foliage marked with every variety of color, and crowned by spike-like firs. On the left is the Slaney, deep and black in its shadows, silver-blue where it reflects the skies, its whisperings interrupted by the occasional leaping of salmon. Looking back to the road, the arches of the bridge, and their clear shadows, form circles which frame in charming bits of landscape. The residence of the Hall-Dare family is almost shut out from the view by trees. It is a mansion of extensive proportions, in the Italian style of architecture. At the end of the long stretch of pasture a stile is crossed, and the paths diverge. One goes down to a favourite bathing place of the boys, the other into the deep shades of the trees on the hill.” – Bassett’s Wexford County Guide and Directory: a book for manufacturers, merchants, traders, land-owners, farmers, tourists, anglers, and sportsmen generally (George Henry Bassett; Dublin: Sealy, Bryers, and Walker, 1885, p.349).

As war was waging in Europe in 1917, the announcement of the engagement of Mabel Bent’s great-niece Audrey provided an opportunity to focus on Ireland’s rural idylls and Mabel herself:- “A Wexford Beauty Spot – The home of Miss Audrey Hall-Dare, whose engagement is announced to Lieutenant H.G. Lee-Warner, of Hawthornedene, Hayes, Kent, is one of the most beautiful in Ireland. Newtonbarry, Co. Wexford, the seat of her father, Mr. Robert W. Hall-Dare, stands on the banks of the Slaney, near the foot of Mount Leinster, and the domain and the whole landscape are very beautiful. The Hall-Dares are really an Essex family, and have a connection with this county extending over two centuries. In Waterloo year Robert W. Hall, High Sheriff of Essex, and member for some years for South Essex, married Elizabeth Dare of Cranbrook House, Essex, and took by royal licence his wife’s surname and arms in addition to his own. Their direct descendent is Miss Audrey Hall-Dare’s father. Mrs. Theodore Bent is a Hall-Dare, and in the course of her wanderings in far-off lands must have viewed many lovely scenes, but it is doubtful whether she has seen a fairer country than that with which she was familiar at Newtownbarry.” The Evening Herald [Dublin], Thursday, February 8, 1917.

Click here for other stylish properties associated with the Bents.

Mabel Bent’s travel Chronicles are available from Archaeopress, Oxford

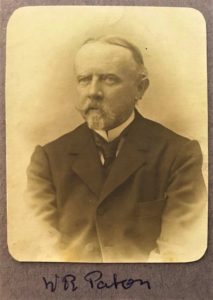

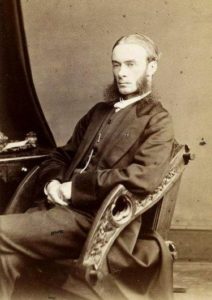

Following on from Alan King’s well-researched, recent piece (September 2019) on the Bents’ friends William (1857-1921) and Irini (1869/70-1908) Paton, it was a pleasant surprise to have access to two unpublished letters from the Paton great estate, Grandhome, just outside Aberdeen – Bent to Paton. In their correspondence, the men refer to recent explorations and successes in Cilicia (notably Bent’s discovery of the site of Olba), and the second letter is of particular interest in terms of Bent’s almost immediate departure for Great Zimbabwe, perhaps his most notorious work. These two letters are published below for the first time and we are most grateful to the present William Paton, Bent’s friend’s great-grandson, for kindly allowing us this opportunity.

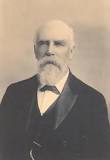

Laird William Paton was a fascinating man of complex nature – a great, perhaps maverick, classicist, traveller and philhellene – it’s not hard to see in him the early shades of later and similar great names, why not Leigh Fermor, Durrell, Pendelbury, Dunbabin…? One can make a fair list.

The only son, William becomes laird of Grandhome after the death of his father, John, in 1879, a JP in 1884, and Deputy-Lieutenant in 1893. But by the mid 1880s he has settled on Kalymnos, running his Scottish estates and managing his responsibilities from a great distance, obviously with a team at home to oversee things (his elderly widowed step-mother, Katherine, survived until 1919), and relying on regular trips back to north-east Scotland: and this trip home from the isles of Greece (then Turkish), by steamer, presumably via Marseilles (the same way the Bents travelled) and Dover and Edinburgh, to Aberdeenshire – a distance of some 4000 km each way; but the Scots are tough and he was young.

Of the two, Bent and Paton, the latter was five years older, and taller, but this didn’t prevent them apparently from being mistaken for bothers, as Mabel Bent was quick (even proud?) to note in her diary:

“We were very much amused on landing [on Kalymnos] to hear ‘William has returned’. ‘No, it is his brother.’ ‘He is exactly the same.’ ‘How very like he is.’ ‘No, it is not him.’ And these sentences never cease to be buzzed round wherever T[heodore] goes. At the British Museum they have been taken for one another and a gentleman came and shook hands with him and said ‘When did you come’ and then ‘Oh! Excuse me. I thought you were the son-in-law of Olympidis’.” (The Dodecanese; Further Life Among the Insular Greeks, Theodore and Mabel Bent, Oxford, 2015, page 159)

Both young men went to Oxford and were intended for the Bar, but both were side-tracked by the lure of ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. Bent had studied history at Wadham and his early studies took him in search of Genoese adventurers on Chios and elsewhere. Paton, the young classicist of rigourous intellect, and self-confessed ‘Orientalist’, soon found himself after University College, hunting for pots and publishing inscriptions in Lycia and Cilicia, inter alia.

Surprisingly, promptly marrying the obviously beguiling and young Irini Olympiti, he settled on Kalymnos, nowadays a municipality in the southeastern Aegean, belonging to the Dodecanese, between the islands of Kos and Leros, and 20 km from the Turkish coast opposite. Soon, along with the even more erudite E.L. Hicks, later Bishop of Lincoln, and also a Bent collaborator (but, another story), Paton became a go-to-man for British academics wanting advice on the region.

Thus, although a truer scholar than Theodore Bent, it is quite natural that they should have met and become acquainted, both lovers of ancient Greece, the new discipline of archaeology, and working on inscriptions in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 1880s; as Mabel noted above, they often bumped into each other at the British Museum, the offices of the Hellenic Society, and many academic events in London and elsewhere.

And we know that Bent at least once travelled up to Aberdeen to stay with Paton, the latter reminiscing in a letter, from Vathy on Samos, in the early 1920s: “I also had the privilege of meeting [E.L. Hicks] personally… at my own house in Scotland, where the late Mr. Theodore Bent and Professor W. M. Ramsay were present, and I had the full advantage of the conversation of these three distinguished people…”

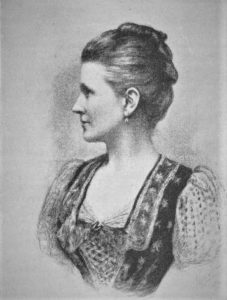

Edward Lear on Greece

“It seems to me that I have to choose between two extremes of affection for nature – towards outward nature that is – English or southern – the former, oak, ash and beech, downs and cliffs, old associations, friends near at hand, and many comforts not to be got elsewhere. The latter olive – vine – flowers, the ancient life of Greece, warmth and light, better health, greater novelty, and less expense in life. On the other side are in England cold, damp and illness, constant hurry and bustle, cessation from all topographic interest, extreme expenses…” [Edward Lear, c. 1860, taken from a letter, in Edward Lear: A Biography by Peter Levi (1995, p. 192)]

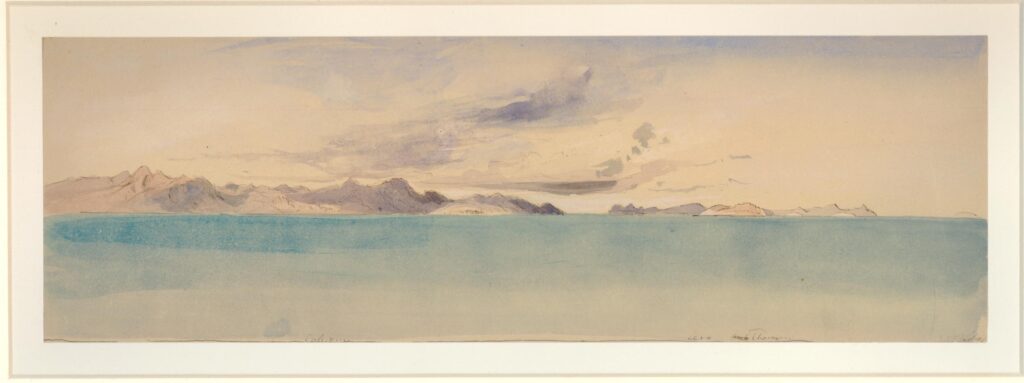

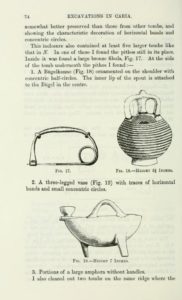

By the mid 1880s, William’s reputation as an epigrapher (and archaeologist, in the terms of the day) was in the ascendancy; any of his published papers reveal a clarity, ingenuity and level of scholarship that soon marked him out. His first major work was at the site of Assarlik (Caria), on the Turkish mainland, on a steep mountain-top in the southern part of the Halicarnassus peninsula, the site offering a perfect view of the coast, both east and west.

He is to publish his findings (1887) as ‘Excavations in Caria’ (JHS 8, 64-82), with, coincidentally, Theodore Bent having an article on inscriptions from Thasos in the same issue (pages 409-438). William had a further piece on ‘Vases from Calymnus and Carpathos’ in the same volume (pages 446-460).

In 1900, the University of Halle awarded him an honorary degree.

W.R. Paton: A select bibliography

1891: The Inscriptions of Cos (With E.L. Hicks)

1891: The Inscriptions of Cos (With E.L. Hicks)

1893: Plutarchi Pythici Dialogoi tres.

1896: (with J.L. Myres) “Karian Sites and Inscriptions”, JHS 16: 188-271.

1898: Anthologiae Grecae Erotica, London, David Nutt.

1899: Inscriptiones insularum maris Aegaei praeter Delum, 2. Inscriptiones Lesbi, Nesi, Tenedi, Berlin.

1915-18: “Greek Anthology”, vols 1-5, Loeb Classical Library/Heinemann, London and New York.

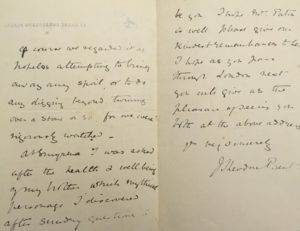

To W.R. Paton, Grandhome, Aberdeen, Scotland [no envelope] note 1

13 Great Cumberland Place, W. note 2 May 27 [1890]

Dear Mr Paton

I am much obliged for your congratulatory note.

From an epigraphical view we have been very successful this winter, having thoroughly solved the problem of Olba and placed one or two other doubtful Cilician towns. note 3

Of course we regarded it as hopeless attempting to bring away any spoil or to do any digging beyond turning over a stone or so, for we were rigorously watched. note 4

At Smyrna I was asked after the health and well being of my brother, which mythical personage I discovered after sundry questions to be you.

I hope Mrs Paton is well, please give our kindest remembrances to her. note 5 I hope as you pass through London next you will give us the pleasure of seeing you both at the above address.

Yours very sincerely

J Theodore Bent

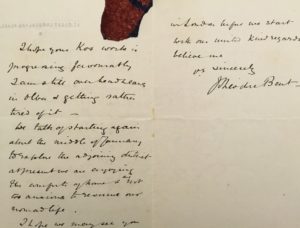

To W.R. Paton, Grandhome, Aberdeen, Scotland [no envelope; the Bent family crest has been torn from the top-left corner] note 6

13 Great Cumberland Place, W. note 7 Oct 15, 1890

My dear Paton note 8

I am writing to ask if you would have any objection to my using one of your admirable photos of Greek costume note 9 to illustrate a frivolous little paper I have written for the English Illustrated on a Greek marriage. note 10 Don’t hesitate to refuse if you have any other plans for your pictures.

I hope your Kos work is progressing favourably. note 11 I am still over head and ears in Olba and getting rather tired of it. note 12

We talk of starting again about the middle of January to explore the adjoining district. note 13 At present we are enjoying the comforts of home and are not too anxious to resume our nomad life.

I hope we may see you in London before we start.

With our kind regards, believe me

Yours sincerely

J Theodore Bent

As a PS, there are two addenda; one a granite obituary in the Aberdeen Daily Journal of 14 May 1921 that covers well the life-journey from Aberdeen to the Greek and Turkish isles:

“The late Mr W. R. Paton of Persley, Eminent Greek Scholar. Greek scholarship has sustained a severe loss in the death of Mr William Roger Paton of Grandhome and Persley, Aberdeenshire, which took place at Vathy, Samos, New Greece [sic], on April 21, in his 65th year. The son of the late Colonel John Paton of Grandhome, the deceased, who was regarded as one of the finest classical scholars in Europe, belonged to a very old and highly respected family which had been in possession of the estate of Grandhome and mansion-house, situated between Parkhill and Stoneywood, for at least 200 years. A number of Mr Paton’s ancestors are buried in Oldmachar Churchyard, and the records of the family go back to 1700. Educated at [Eton] and at University College, Oxford, Mr Paton very early acquired a strong interest in everything connected with Greece, and particularly with Greek literature. He had already done a good deal of Greek study before he left in 1893 to take up his residence in France. For a number of years he had lived in the island of Samos, in the Aegean Sea, travelled in Asia Minor and among the Isles of Greece, and made a number of important contributions to Greek literature. In particular, he edited the works of Plutarch, and was preparing a large edition at the time of his death. He also collected many inscriptions found in the Aegean Islands; and his archaeological discoveries in Lesbos, Tenedos, and other isles of the Greek Archipelago were communicated to the Berlin Academy and form part of the Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum. He published an edition with translations of the love-poems and epigrams in the Greek Anthology. Mr Paton was recognised as one of the greatest Greek authorities of his time. His scholarship was of a very finished character, and he had also a wide knowledge of modern Greek. No one really knew more about Greek life, thought, and literature in all periods, and he was man of remarkable accomplishments, who if he had not been a country laird would have adorned a University chair… In 1900 the University of Halle conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws on Mr Paton. Personally Mr Paton was a man of charming manners and a delightful companion of the most finished culture. A year or two ago he was expected to come home and spend the end of his days in Aberdeen, but he did not carry out his intention. Mr Paton was twice married to Greek ladies, and he leaves a widow and family. He died on 21 April 1921 in the town of Vathy, Samos.”

A final and quirky note goes to J.H. Fowler, who was in touch with Paton while compiling a memorial volume to E.L. Hicks (see above). He gives us this astonishing, perhaps envious, pen-portrait of Paton:

“At this time too [Hicks] became associated with another Greek scholar, Mr. W. R. Paton, who took up his abode in the Island of Cos and made a careful collection of the inscriptions to be found there. Hicks collaborated in the deciphering and interpretation of the inscriptions, and wrote the introduction for the Inscriptions of Cos (Clarendon Press, 1891). A friendship grew up between the two men, unlike as they were, the one equally at home in the practical and in the theoretical life, the other a dilettante scholar who became at last so completely ‘orientalized’ (to use his own expression) that he was reluctant to revisit England, and who never earned anything in his life till he was paid for his translations from the Greek Anthology in the Loeb Library.”

Nowruz (or “no rooz” for Mabel), a moveable feast, is the Persian New Year, and the Bents found themselves caught up in the celebrations for it in the Spring of 1899, during their amazing journey on horseback, south–north, through Persia that year. Theodore wrote a piece on it; Mabel makes several references to it in her ‘Chronicle’ – they were even introduced to the Shah, who takes an obvious shine to Theodore’s wife. Nowruz 2020, by the way, is March 20th.

Nowruz (or “no rooz” for Mabel), a moveable feast, is the Persian New Year, and the Bents found themselves caught up in the celebrations for it in the Spring of 1899, during their amazing journey on horseback, south–north, through Persia that year. Theodore wrote a piece on it; Mabel makes several references to it in her ‘Chronicle’ – they were even introduced to the Shah, who takes an obvious shine to Theodore’s wife. Nowruz 2020, by the way, is March 20th.

Eight Western New Years out of fourteen saw the intrepid Bents on the road somewhere, or at sea, leaving freezing, foggy England (and their fine townhouse near Marble Arch) in their dust either for the Eastern Med, Africa, or wider Arabia, where they would spend three months or so exploring for antiquities, customs, costumes, folklore, and any other material Theodore could weave into a book, article or lantern-slide talk (based on Mabel’s photos).

Trekking, the Bents seem too preoccupied or tired to do too much in the way of celebrations, and they were moderate in their habits anyway. Perhaps the two occasions they were at sea on comfortable steamers might have been more jolly; but Mabel makes no mention.

If you have an idle few minutes you can follow the couple via these interactive maps on our site.

For those who enjoy lists, here is where the Bents celebrated, or slept through, New Year’s Eve away from London, between 1883–1896 (Theodore’s last New Year – health? It brought him none; he died of malarial complications in May 1897, at only 45).

New Year’s Eve 1883 – Naxos in the Cyclades

New Year’s Eve 1888 – On their way to Aden on the P&O Rosetta

New Year’s Eve 1891 – On the return journey from Cape Town to London on the Castle Line Doune Castle

New Year’s Eve 1892 – En route to Massawa in the Red Sea

New Year’s Eve 1893 – Trekking monotonously through the Wadi Hadramawt, Yemen “[Sunday, 31 December 1893] Our journey was utterly monotonous and again we camped near wells. Lunt’s tent [their botanist from Kew] put up the first thing for him to get to bed with orders not to leave till the sun was on us in the morning, and we all decided to stay at home till that time as again the camels could find food. I like camping near water because the camels can fetch it quietly from the wells instead of noisily from their own insides.”

New Year’s Eve 1894 – Dofar “New Year’s Eve. Did not get off till 10, though we breakfasted before sunrise. Every rope we had round our boxes is taken off and in use, and every bit of rawhide rope we possess is in use and great famine prevails in this respect. Theodore’s camel was a very horrid one and sat down occasionally and you first get a violent pitch forward, then an equally violent one back and a 2nd forward; this is not a pleasant thing to happen unexpectedly… We were all most dreadfully stiff and tired and again too late to do anything in the way of unpacking more than just enough for the night.”

New Year’s Eve 1895 – Kosseir (modern Quseir/Qoseir) in the Red Sea: “New Year’s Eve 1895. We went ashore in a bay guarded by savage reefs, and were glad to leave our rolling ship. There was a good deal of vegetation and Theodore seriously began his botanical collection with a good booty. Nothing was shot but 2 birds, which fell into the sea and were snapped up by a shark.”

New Year’s Eve 1896 – Socotra

If you want to read Mabel’s New Years, her ‘Chronicles’ (archived in London, under the care of the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies) have been published by Archaeopress, Oxford.

Neither a firm of county-town solicitors, nor nonsense to soon find a link between Theodore Bent and Edward Lear (1812-1888). The Oxford academic and traveller to the Eastern Med, Henry Fanshawe Tozer (1829-1916) – himself somewhat Learesque – visited the artist, a lover of Greece, but by then too infirm to travel, in his San Remo villa in 1885, and sent him a copy of Bent’s newly published and seminal work: The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks (London, 1885).

In the 9 May 1885 issue (no. 679, pp 322-3) of The Academy, Tozer submitted a full and waspish review of Bent’s now-famous book. The review is a great read, something of a series of fierce island landscapes of its own, in all seasons. He lets rip, but ends charitably, in a manner fitting for a man of the cloth: “But this does not much detract from the usefulness of the book as a unique description of the life and ideas of a people, which renders it a very storehouse of facts for the student of customs and myths. And in this respect its value will be permanent. Other travellers may follow in Mr. Bent’s footsteps [millions in fact], and fill up what is wanting in his archaeological information; but in a few years’ time, if any traveller be found so enduring as to attempt once more the task which he has so well performed, it is highly probable that a great part of these interesting customs and ideas will have disappeared.” Very true, and now the islands are an ordeal in summer for any but teenagers – some of the blame can be lain at Bent’s door perhaps. Incidentally, Tozer’s 1890 book The Islands of the Aegean has been long forgotten.

Lear is soon writing to his friend Chichester Fortescue: ‘Tozer of Oxford sends me a charming book…by Theodore Bent…all about the Cyclades. (Dearly beloved child let me announce to you that this word is pronounced ‘Sick Ladies,’ – howsomdever certain Britishers call it ‘Sigh-claides.’)…’ (Lear to Chichester Fortescue, Lord Carlingford [30 April 1885, San Remo]).

Lear, like Bent, struggled with the tug between sunshine and showers:

“It seems to me that I have to choose between two extremes of affection for nature – towards outward nature that is – English or southern – the former, oak, ash and beech, downs and cliffs, old associations, friends near at hand, and many comforts not to be got elsewhere. The latter olive – vine – flowers, the ancient life of Greece, warmth and light, better health, greater novelty, and less expense in life. On the other side are in England cold, damp and illness, constant hurry and bustle, cessation from all topographic interest, extreme expenses…” [Edward Lear, c. 1860, taken from a letter, in Edward Lear: A Biography by Peter Levi (1995, p. 192)]

In the Collections Development Policy statement (2011) of the Harris Museum and Art Gallery (Preston, UK) there is a fascinating, and, for the Bent Archive, startling reference on page 30:

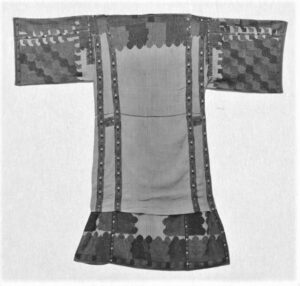

‘In the long term, the following areas of the collection have been identified as under-researched areas, but these would only be tackled in the context of potential for use and visitor engagement … […] Theodore Bent’s Turkish embroidery bequest.’

This casual aside makes the Harris Museum one of only three public collections in the world, to our knowledge, to hold a collection of textiles originally acquired by Theodore and Mabel Bent over the 20 years of their travels, the other two being the Benaki Museum, Athens, and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. (We are not including here the few clothing and other items, some made of bark, that the Bents brought back from Great Zimbabwe that are now in the British Museum.)

‘Theodore Bent’s Turkish embroidery bequest’ at the Harris Museum consists of four items (we are assuming they represent the entire ‘bequest’), and, thanks to the kind assistance of curator Caroline Alexander, we believe that this is the first time they have been ‘published’.

The museum’s Accession Book refers to the pieces as ‘Turkish Embroideries’. In the 1880s, the decade the Bents spent mainly in the Eastern Mediterranean, the islands off the Turkish west coast belonged to Turkey, taken and held by the Ottomans from early medieval times until the early 20th century. The Dodecanese islands were only returned to Greece in the 1940s. Thus the Bents’ acquisitions of fabrics and costumes (some with the intention of selling on to British collectors and institutions) reflect a wide blend of styles and influences – the distinctions between ‘Greek’ and ‘Turkish’ being generally moot points. Beautiful things, made painstakingly, to be given, worn, or displayed, remain beautiful things irrespective.

The four items (1970.1; 1970.2; 1970.3; 1970.4) in the Harris Museum were donated in May 1970, rather mysteriously, by someone who introduced herself as ‘the great-niece’ of Theodore Bent. There seems to be no mention of the gift in the museum’s Donation Book, an interesting fact, nor does any name appear in the museum’s accession records unfortunately. The museum’s Accession Book includes the following handwritten note stapled to the relevant entries: ‘Query re T. Bent’s niece [sic]. No details of this donation in the donation book. Contact V & A to whom T. Bent donated embroidery.’

Enquiries are under way (December 2019) to try and find out who the donor may have been, and why the Harris should have been chosen as the recipient.

Theodore Bent had no siblings, but several cousins, who in turn had issue. There is a chance that one of these might be our donor, and there is a local connection. Theodore Bent himself had property just outside Macclesfield , and his uncle John was Lord Mayor of Liverpool in 1850. The family were influential local brewers, and, indeed, Theodore was born in Liverpool (1852). Bent’s Brewery Co. Ltd remained in business until the 1970s, as part of Bass Charrington. The Bents can be traced back to the Liverpool region in the 1600/1700s, and were potters and brewers – one, a medical man, was the famous surgeon who amputated Josiah Wedgwood’s leg!

Thus perhaps it was a member of this energetic and successful family who donated the embroideries in 1970; but somehow we doubt it. The Bents were great collectors (and dealers) in embroideries, etc., on their travels in the Eastern Mediterranean and Turkey in the 1880s, the period, we assume, when the four pieces now in the Harris were acquired by the exploring couple. On Theodore’s death in 1897 all his estate went to his wife Mabel, and they had no children. Just over thirty years later, on Mabel’s death (1929) all her belongings, including her textiles, went to her surviving nieces – they, in turn, had daughters, who would thus have been the ‘great nieces of Mrs Theodore Bent’. Of these, it seems only Kathleen Prudence Eirene Bagenal (1886-1974) was alive in 1970. (For the Anglo-Irish Hall-Dare family click here.)

We may, therefore, tentatively, and for now, propose Kathleen Bagenal (or her agent) as the donor of the Bent textile bequest to the Harris. The mystery remains why the Harris? Kathleen’s family home was in Scotland (Arbigland, on the Solway Firth), and we know that she was actively selling off her great-aunt’s textiles from the 1930s. We will, of course, update this theory if more information comes our way.

In her lifetime Mabel exhibited some of her fabric collection – we know of two events, but neither seem to have included any of the four items donated to the Harris in 1970.

The Bent textiles in the Harris Museum, Preston

PRSMG: c1970.1 [Headed ‘Turkish Embroidery’ in the museum’s Accession Book]

Accession Book entry: ‘Embroidered with silk and gold plate thread, at both ends. Repeating pattern of formal plant motifs. Pink, blue, gold and brown on natural linen.’ Acquired from: ‘The great-niece of Theodore Bent’. Acquisition dated: ‘April May 1970′.

Digital catalogue entry: ‘Fine linen cloth [dimensions not provided] embroidered at both ends with intricate floral pattern of mainly peach and blue silk embellished with gold. Probably embroidered using a tambour. Possibly Turkish. Note: 2015, Asia from British Museum visited, said possibly Turkish with the use of flattened gold thread.’

PRSMG: 1970.2 [Headed ‘Turkish Embroidery’ in the museum’s Accession Book]

Accession Book entry: ‘Short strip embroidered at ends with formal design of cyprus tress and flowers in urns. Embroidered patch appliquéd on.’ Acquired from: ‘The great-niece of Theodore Bent’. Acquisition dated: ‘May 1970′.

Digital catalogue entry: ‘Embroidered panel [dimensions not provided] of fine linen. Embroidered both ends with motifs of pinecones and eight-petalled flowers in pots worked in blue, dark brown beige and cream threads. Probably machine worked as no evidence of starting or finishing. Machine worked down two edges. Also central panel later addition in pale blue, beige and cream floral motifs.’

PRSMG: 1970.3 [Headed ‘Turkish Embroidery’ in the museum’s Accession Book]

Accession Book entry: ‘Long strip embroidered with flower motif repeated seven times. Red, brown and blue silk embroidery with blue border on three sides.’ Acquired from: ‘The great-niece of Theodore Bent’. Acquisition dated: ‘May 1970′.

Digital catalogue entry: ‘Embroidered panel of fine linen [dimensions not provided]. Embroidered with floral motifs along length. Motif of red and blue flowers in repeated and alternating pattern. Appears to have been the edge of a larger panel. Believed Turkish c 19th century.’

PRSMG: 1970.4 [Headed ‘Turkish Embroidery’ in the museum’s Accession Book]

Accession Book entry: ‘Red silk cloth square extended at corners. Two embroidered panels joined to form centre piece, with blue silk strips on two sides. Floral design.’ Acquired from: ‘The great-niece of Theodore Bent’. Acquisition dated: ‘May 1970’. [This entry in a different hand]

Digital catalogue entry: ‘Embroidered panel [dimensions not provided] of floral motifs on fine linen comprising two pieces joined in the centre. Primarily terracotta red, blue, green and mustard thread working arabesque floral design. Panel has terracotta coloured narrow lace edging. Panel has been mounted on dark red silk backing panel with sleeves top and bottom for hanging. Possibly Turkish. c 19th century.’

The 1914 embroidery exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, London

As mentioned above, Mabel Bent showed a good part of her collection at the 1914 embroidery exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in London. There is an an online catalogue. The prize exhibits were a collection of fine dresses from the Dodecanese, now in the Benaki Museum, Athens, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The exhibition cabinets displayed a wide range of Mabel’s other textiles, but none of the four items now held in the Harris Museum seem to have been shown to the public in 1914, but more research is needed to confirm this (i.e. future access to the exclusive photographs of the exhibits). Readers may be able to identify the Harris pieces in the catalogue (search ‘Bent’ in the online catalogue search box that appears on the page), and if so we would be delighted to hear from them. Similarly, if any Preston readers can provide information on the four Harris pieces before they entered the collection in 1970, we would also be most interested.

Mabel Bent’s diaries are, occasionally, a useful primary source for information on the thousands of artefacts the couple returned with to London during the twenty years of their travels in the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and Arabia. There are hundreds of references to dress, costume, embroideries, fabrics, etc. Unfortunately, Mabel does not always give precise details of gifts and acquisitions and it has not been possible to identify the four textiles in the Harris bequest in her notebooks.

“This afternoon we have been to the doctor Venier, of a Venetian family. Dr. Venier showed us the hangings of a bed, in which King Otho slept when he visited Pholégandros. All gold lace, silver lace and the most beautiful silk embroidery on linen. The curtains were striped silk gauze with gold lace insertion. The pillows gold edged real silk. We were also shown lace-edged sheets and gold embroidery. It was a really splendid sight and fit for a museum.” (February 1884, Folégandhros in the Greek Cyclades; ‘The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent’, vol 1, page 44, 2006, Oxford)

In conclusion, the four textile pieces discussed, once in the collection of Theodore and Mabel Bent and donated to the Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, represent an important revelation, and are published, it is thought, for the first time here. If you have any comments on any aspect of this content, including the origins, or technical/stylistic features of the four textiles, do please write in.

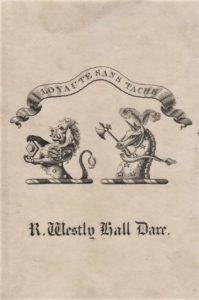

We all know that books attract to us like iron filings to a magnet, and that, mysteriously, over the decades, the poles reverse, and they fall away, mostly unmissed. Their residue? – more than likely some brown envelope stuffed with futureless bookplates.

Here is one, it came to the Bent Archive the other day (late November 2019) after a casual search online. It is the bookplate of Robert Westley Hall-Dare (1789-1836), the 1st, the explorer Mabel Bent’s grandfather. (Tradition had it that the eldest boy would subsequently have the same name, thus RWHD II (1817-1866) was Mabel’s father; RWHD III, her brother (1840-1876); RWHD IV, her nephew (1866-1939); and RWHD V (fifth and last, 1899-1972) her great-nephew. Pedants will have spotted ‘Westly’ for ‘Westley’ – it’s no typo; early family members were flexible.)

(For the background to the extended Hall-Dare family (in 1912), see Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (1912, London, pp. 165-6.)

There was substantial wealth in the Hall-Dare family – rich estates in distant sugar-lands and not-so-distant Essex. Eton and Oxford boys, the Hall-Dares had lots of books, and bookplates for them. For their coat-of-arms, assembled from various matrimonial alliances (Dare, Hall, Westley/ Westly, Eaton, King, Grafton, Mildmay, et al.), we have only to turn to page 263 of Burke’s 1884 edition (London) of The general armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales; comprising a registry of armorial bearings from the earliest to the present time.

The mortal remains of Mabel’s grandfather rest in the family vault in St Mary’s Church, Theydon Bois, Essex. There is a memorial bust to her great-grandfather (Robert Westley Hall, died April 13, 1834) by the sculptor Patrick Macdowell in St Margaret’s Church, Barking, Essex.

No doubt there will be those now in candlelit studies, ticking grandfather clocks, cigars, brandy glasses on green-baize tables, who will be waiting for a description. Here it is in full:

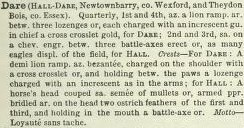

“Dare (Hall-Dare, Newtownbarry, co. Wexford, and Theydon Bois, Co. Essex). Quarterly, 1st and 4th, az. a lion ramp. ar. betw. three lozenges or, each charged with an increscent gu. in chief a cross crosslet gold, for Dare; 2nd and 3rd, sa. on a chev. engr. betw. three battle-axes erect or, as many eagles displ. of the field, for Hall. Crests — For Dare: A demi lion ramp. az. bezantée, charged on the shoulder with a cross crosslet or, and holding betw. the paws a lozenge charged with an increscent as in the arms; for Hall: A horse’s head couped sa. semée of mullets or, armed ppr. bridled ar. on the head two ostrich feathers of the first and third, and holding in the mouth a battle-axe or. Motto — Loyauté sans tache.”

“Dare (Hall-Dare, Newtownbarry, co. Wexford, and Theydon Bois, Co. Essex). Quarterly, 1st and 4th, az. a lion ramp. ar. betw. three lozenges or, each charged with an increscent gu. in chief a cross crosslet gold, for Dare; 2nd and 3rd, sa. on a chev. engr. betw. three battle-axes erect or, as many eagles displ. of the field, for Hall. Crests — For Dare: A demi lion ramp. az. bezantée, charged on the shoulder with a cross crosslet or, and holding betw. the paws a lozenge charged with an increscent as in the arms; for Hall: A horse’s head couped sa. semée of mullets or, armed ppr. bridled ar. on the head two ostrich feathers of the first and third, and holding in the mouth a battle-axe or. Motto — Loyauté sans tache.”

The motto is archaic French; nothing to do with troubling Victorian moustaches: Fairbairn (Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland, 1905, part II, page 47) gives us “Loyalty without spot” – unblemished loyalty, large words to live up to, or not.

In the Government Gazette (India) for Thursday, 8 April 1824, we find Hall-Dare listed as a founding Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

But, to return to our theme, a bookplate without book… is still a book lost…

Mabel, Theodore, and Thomas Cook & Son

In the news once more, the seemingly persistent vicissitudes of the once-venerable Thos Cook & Sons (and all so symptomatic of British management for decades, especially in terms of brand stewardship) have sent the Bent Archive (late August 2019) back to Mabel’s diaries for references to the eponymous tour operator – for the couple, like thousands, tens of thousands, of travellers– relied upon Thomas Cook (1808-1892) for their occasional Nilotic episodes in the 1880s and ‘90s. The entrepreneur began his Egyptian tours in 1869.

Some background; Jan Morris, none better: “Thomas Cook, the booking clerk of the Empire… and ‘leave it to Cook’s’ had gone into the language. Cook’s had virtually invented modern tourism, and their brown mahogany offices, with their whirring fans and brass tellers’ cages, were landmarks of every imperial city. They held the concession for operating steamers on the River Nile: all the way up to Abu Simbel the banks of the river were populated by Cook’s dependents…’ (‘Pax Britannica, The Climax of an Empire’. London 1998, page 64)

The Bents’ first reference to the firm is in early 1885. Theodore and Mabel are off to explore the, then Turkish, Dodecanese, but opt to start with the steamer from Marseilles to Alexandria, via the Straits of Messina, and a brief detour to Egypt. Mabel busies herself with her diary:

“In the evening of Saturday [17th January 1885] we went out to see Stromboli. We could dimly distinguish the fire but when lightning swept low on the sea behind it the whole black form of the island was shown. We went very slowly, whistling through the Straits of Messina. We ought to have been in Alexandria on Tuesday but only got to the desired port about 2 o’clock on Wednesday [21st January], quite as glad to get into the Land of Egypt as ever the Children of Israel were to get out. We had our little feelings as we sat in a boat with a Union Jack and ‘Cook’s Tours’ upon it. We got through the custom-house very well and my box of photographic things was never opened anywhere though it was hastily put into a box with ‘Matière Explosive, Dynamite’ upon it.” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 2, Africa’. Oxford 2012, page 6)

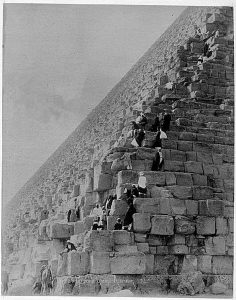

Moving on from the port of the famous Library, a few pages further in her diary Mabel details their sightseeing around Cairo – and, of course, at the Sphinx and its sentinels. Then, as now, tourists everywhere are suspended by their heels and well shaken; Mabel, in charge of the Bent coffers, is having none of it: “Monday 26th [January 1885]. By the bye, [Thomas] Cook, when asked, would send us to the Pyramids for £3 and I think we only paid £1 and 1 franc.” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 2, Africa’. Oxford 2012, page 11)

The Bents’ first visit to Egypt was carefree and fun; Mabel’s diary pages read whimsically and breathless in 1885. Not so in 1898. Theodore’s (early, aged 45) death in May 1897 – Jubilee year – deprived Mabel of the focus for her life: the need to be somewhere else remained, but now with whom? And why? Typical of her she made plans immediately to visit Egypt on a ‘Cook’s’ tour in the winter of 1898 and chronicled the trip, ending with a return via Athens. The melancholy heading she gives this section of her diary is – ‘A lonely useless journey’. Her writing reveals her understandable depression. It makes unhappy reading, contrasting so markedly with her opening thrill of being in Cairo on that first visit with Theodore in 1885.

No doubt encouraged by her relatives, Mabel elected to put together for herself a ‘Cook’s Tour’ to Egypt and the Nile. But, often a mistake to revisit sites of earlier happiness, Mabel’s Egyptian pages echo a series of muted contrasts, sighs, and signs of near despair. That image of a confident, smiling Mabel climbing the Giza Pyramids on her birthday in 1885 is not the one that reappears as she groans ‘so sadly to Mr. Aulich’ of the Cairo Hôtel d’Angleterre, or rides ‘alone and unknown and unknowing’ around the great sites.

The famous travel company, however, is soon on the scene. They do their best to cheer her up: “Wednesday 19th [January 1898]. Port Said… We reached Ismailia about 10 p.m. I landed myself quite unaided and got to bed while the people [Thomas] Cook’s man was looking after, and a lady met by a government officer, were still in the custom house. I took a walk in the town next morning and started for Cairo… I was horrified by a note from Mr. Aulich, the manager of the Hôtel d’Angleterre, to say neither he nor the [Grand] Continental had a room and one had been taken in the Hôtel du Nil. I dined among many Germans, with their napkins tucked under their chins, leaving their elbows on the table and picking their teeth. My cupboard had such smoky coats hung in it that I dared not put in my dresses. Friday 21st [January 1898]. I went and groaned so sadly to Mr. Aulich that a garret was found for me – no bell or electric light – and thither I took myself before dinner. As I was in the Mouski, I thought I could walk in the bazaars so I put on my hat and made the best of my opportunity. Saturday 22nd [January 1898]. I went to Cook’s arsenal and chose a saddle to come with me with one of my own stirrups. On Saturday also I did all my final shopping and remembered when we were last here (or last but one). How we laughed …” (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 2, Africa’. Oxford 2012, page 268)

Mabel is writing on her Nile cruise boat. By 1904 the Cook Nile fleet comprised all these paddle-steamers (P.S.) for First Class passengers: ‘Rameses’ (236x30ft); ‘Rameses the Great’ (221x30ft); ‘Rameses III’ (200x28ft); ‘Amasis’ (170x20ft); ‘Prince Abbas’ (160×20 ft); ‘Tewfik’ (160x20ft); ‘Memnon’ (131x19ft). The steam ‘dahabeahs’ included the ‘Serapis’ (125x18ft); ‘Oonas’ (110x18ft); ‘Nitocris’ (103x15ft); and ‘Mena’ (100x18ft). Although Cook’s still have records for most of their steamers that travelled the Nile between 1890-4, they have no details for the period 1895-1900 and no booking records for Mabel’s journeys have been found (Cook’s Company Archivist, pers. comm., 2012).

Over the next few weeks (February 1898), Mabel makes several more references to Cooks as she visits the great sites and sights. The company, it seems, provides all comforts and care: “Thursday, February 3rd [1898]. Medinet Habou, Colossi, Dier el Bahàri, Gourna Ramesseum, and after tea I did the Luxor Temple alone; so nice and quiet and much less lonely than among so many strangers. Up to this we had awfully cold weather. I had, besides the Cook’s blanket and quilt, 2 blankets of my own, a shawl, dressing gown, newspaper, cloak and Ulster on my bed.” (The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 2, Africa. Oxford 2012, page 270)

On 22 February 1898 she has a visit by the famous man himself: “Reached Luxor Tuesday evening, but did not go to live ashore at the Luxor Hotel till Wednesday. Mr. Cook came on board that evening with Major and Mrs. Griffiths, off his dahabeyah ‘Cheops’, which we had been towing all day. (‘The Travel Chronicles of Mabel Bent, Volume 2, Africa’. Oxford 2012, page 273)

Although with only a year to live, Mabel’s ‘Mr. Cook’ here is John Mason Cook (1834-1899), the only son of the founder, Thomas. The Luxor Hotel, to the east of Luxor Temple, was established by Cooks to accommodate the increasing number of tour groups along the Nile.

After Theodore’s death Mabel met the designer Moses Cotsworth in the Middle East and provided another Cook’s story. Moses had sailed to Beirut in December 1900 to visit the Sun Temple at Baalbek. In Beirut, he was ‘stranded in quarantine’ at Thomas Cook’s travel bureau. It was too late in the season for tourists to attempt the overland journey to Jerusalem and he was unable to afford a private guide. While waiting there he overheard a conversation between some other travellers who were also trying to attempt the same trip. Professor G. Frederick Wright and his son, Fred, were talking to Rossiter S. Scott from Baltimore, USA. They all wished to travel to Jerusalem. Wright invited Cotsworth to join their party as between them, and Scott, they could afford to hire a guide. The party set out for Damascus by the narrow-gauge railway over the mountains of Lebanon taking a slight detour for Cotsworth to visit Baalbek. By 17th December they had reached Damascus and organised a caravan of mules to carry them to Jerusalem. They had no tents but ‘depended on finding shelter wherever we should happen to be.’ In Hineh they sought shelter in the house of a Russian priest and had to remain there for two days to escape a snowstorm. Once on the move again they passed Lake Huleh where they were accosted by a Bedouin gentlemen who spoke English and asked them to drink coffee with him. The party then planned to visit the southern end of the Dead Sea. Wright recounted that ‘In this we were joined by Mrs. Theodore Bent, whose extensive travels with her husband in Ethiopia, southern Arabia, and Persia, had not only rendered her famous but fitted her in a peculiar manner to be a congenial and helpful travelling companion.’

Cook’s, of course, went bust inevitably and finally in September 2019 and future Mabels will no longer take to their beds, board, berths, flights, guides, and countless other services. Nor will their agents still greet them, smiling, at stations, harbour-sides, arrival gates, and pullman halts. Never more (unless reincarnated) will there be, Morris again, “Thomas Cook, the booking clerk of the Empire…”? All aboard? All abroad?

Mabel’s diary extracts are from Volume 2 of her Chronicles.

VIDEO – Manolis Pelekis: A lament for the great tsabouna player from Anafi.

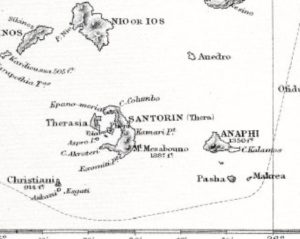

The Bent Archive has been slow with its tribute to the late Manolis Pelekis (†2019) – legendary Anafiot citizen, musician and tsabouna player; for many decades no Anafi island event (Greek Cyclades, east of Santorini) was ever complete without his plaintive accompaniment…

Theodore and Mabel Bent, tsabouna serenaded, travelled in the Cyclades in 1883/4, recording many occasions of musical evenings in their writings; here is Mabel in her diary in early 1884 making reference to an Anafi ball (probably hearing somewhere the skirls of the tsabouna): “After dinner a fine tall handsome niece of Matthew’s called Evtimia Chalaris [appeared], dressed in a beautiful old costume of silk, violet flowered brocade skirt, green velvet bodice, gold embroidered stomacher and a short pink satin jacket edged round the cuffs and down the front with pink fur… There was a regular ball and the Demarch danced most actively.”

The Matthew referred to is the Bent’s long-serving assistant Matthew Simos, who was born on Anafi.

A year later, 1885, Theodore Bent acquired a tsabouna of his own – it is now on display in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. The couple were great collectors of things to make music with – wherever they travelled to. The British Museum has some of their instruments from Zimbabwe, and the Pitt Rivers also holds a lyra from Karpathos and various Cycladic pipes made from eagle bones, and other items. It’s time for a themed display with musical offerings for enthusiasts.

The main difference to the instrument played by Manolis Pelekis (over 100 years later) is that Bent’s Oxford tsabouna lacks the poignant brass cross on the chanter…

RIP Kyrie Manolis; listen to him play…

(The video of Manolis is an excerpt from a longer YouTube film you can see here.)

The tsabouna has a special place in the repertoire of the Cyclades and greater Greece; its history and etymology are fascinating. Take a look at our video exploring Theodore’s relationship with the instrument.

Coincidentally, on Santorini, just two hours east of Anafi (although it took the Bents close to twenty), you will find the musician Yannis Pantazis who crafts his own instruments and demonstrates them in his artisan workshop in Santorini, at SYMPOSION by La Ponta, in the traditional village of Megalochori.

Theodore Bent’s ‘The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks’ is available from Archaeopress, Oxford, as are Mabel Bent’s travel Chronicles.

Happy anniversary. August 2nd is Theodore and Mabel’s wedding anniversary – they married (he 26, she 31) near Mabel’s family seat (Co. Wexford) on this day in 1877, in the little church of Staplestown, Co. Carlow.

The couple were perfectly matched and formed a happy, childless partnership, spent exploring for nearly the next 20 years the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa and Arabia, until Theodore’s untimely death in May 1897, returning from east of Aden – as fatal then as now.

We know the couple met in Norway, probably c. 1876, but the date/place has yet to be discovered. By May 23 the engagement was announced (e.g. The Morning Post, May 23, 1877. The wedding, as noted above, was August 2 – not very long to organize the event on both sides of the Irish Sea. It was clear that Theodore had no intention of residing in his native Baildon, Yorkshire. Both his parents were dead and within weeks of the wedding he was selling off parcels of his land there, e.g. at the Bradford Finance and Local Purposes Committee meeting of Tuesday, 14 August 1877, one of the items reports that it was agreed “to accept the offer of Mr. James Theodore Bent to sell to the Corporation certain lands and hereditaments situate in the township of Baildon, containing 25 acres, 2 roods and 18 perches, for the sum of £4,000… With regards to the purchase from Mr. Bent, it was of land lying on this side of Esholt, at a tolerably level portion near the river. The purchase was recommended with a view to using the land for sewage defœcation purposes, should it be required.” (Leeds Times, Saturday 18 August 1877). The sum is the equivalent of £250,000 or so today – a nice wedding present.

Mabel was brusque, pragmatic, robust, fearless, obsessive and totally dedicated to Theodore’s work – their work – as expedition quartermaster, photographer, and chronicler. She was also to the right of fanatical. Theodore died in days, and Mabel found herself equally abruptly adrift – she turned to her faith and spent several years rootling around Palestine, soon becoming embroiled in the early doings of the Anglo-Israeli Association (various aliases) and remained a member for 30 years until her death in 1929. (One of the many archaeological ironies is that co-adherents desecrated the ‘Hill of Tara’ (Co. Meath, and just a few kms south-east of Mabel’s birthplace) in the early 1900s, looking for the ‘Ark of the Covenant’; and there is the on-going controversy about ‘The Bethel Seal’ – did Mabel plant it as a love-token for her dead spouse?)

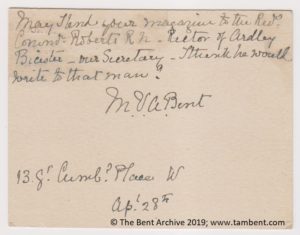

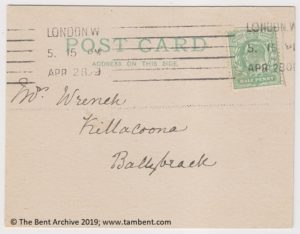

And the reason for the anniversary nod to her, anyway, is just to point out this aspect of Mabel’s nature (and he that is without, etc.), and note the arrival at the Bent Archive (thanks to Anna Cook) of a signed and incompletely dated card from Mabel to Charlotte Bellingham Wrench (addressed to her fine house, Killacoona, Ballybrack, Co. Dublin), asking if she (Mabel) could forward a magazine (presumably anti-AIA) to Lawrence Roberts, ‘our secretary’ (and committed AIAist), and write to ‘that man’ (Mabel could be a dogged and ruthless adversary).

Never mind, ‘Ní bheidh a leithéid ann arís – Her like will not be seen again’ (as goes the Irish epitaph later selected for one of Mabel’s great-nieces). She is buried with Theodore in St Mary’s, Theydon Bois, outside London, go visit her…