Socotra and East of Aden: The Bents’ final journey – November 1896 to April 1897

“Mrs. Theodore Bent had advised us to obtain as guides two Sokotri, Amr and Ali, who had accompanied her husband and herself and been very useful to them during their visit to Sokotra. On making a request for their services from the Sultan, both men, strange to say, were standing close by me among the throng that had followed us into the reception room, and were forthwith told to attend us and see to our requirements at a charge to us of one and a quarter rupees per day. If these men had proved faithful and helpful to the Bents, they had been much spoiled by them, or had vastly deteriorated in character since their visit. They had bled these travellers very freely, we gathered, and we soon found out for ourselves that unless we were prepared to pay the Bent tariff, we should meet with opposition everywhere. Both men were entirely subservient to the Sultan — Ali, indeed, was his slave, and half of Amr’s and all Ali’s pay would go into His Highness’s pocket. A very short term of probation served to show them in their true characters, and had we not put our foot down and dismissed them after about a fortnight’s employment, we should have experienced more trouble and greater delays than we did.” (The Natural History of Sokotra and Abdel-Kuri: Being the Report Upon the Results of the Conjoint Expedition to These Islands in 1898-9, by Mr. W.R. Ogilvie-Grant and Dr. H.O. Forbes, Liverpool, 1903, xxxi-xxxii).

Mabel’s final travel Chronicle in the company of her husband Theodore Bent is one of her most readable. She begins it in November 1896 with a calligraphic flourish suggestive of the couple’s eagerness to be travelling once more and returning to Southern Arabia after an enforced switch of focus to the Sudan for their Winter 1895/Spring 1896 expedition.

After their return in April 1895 from a curtailed attempt to enter the Hadhramaut from Dhofar, to the east, and ending with a frustrated Theodore steaming to Bombay to try and secure further British approval to survey up the Wadi Masila, the travellers settled down in London to prepare and lecture on their findings in Oman to the London and regional institutions as usual.

For example, the Bents were lecturing in Glasgow late in 1895, Theodore using lantern slides prepared from Mabel’s photographs: “The anniversary address in connection with the Glasgow Branch of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society was given last night [Thursday, Nov 7, 1895] in the Society’s Hall, 207 Bath Street, Glasgow. Sir William Renny Watson presided, and introduced in a few well-chosen remarks the lecturer – Mr. J. Theodore Bent. Mr. Bent in his lecture, which was illustrated with lime-light views, went over the greater part of Southern Arabia, speaking of the country, its people, and their occupations, religions, and habits, and imparting a vast amount of interesting information upon his subject. A hearty vote of thanks was passed to him at the close of the lecture.” (The Daily Record, Friday, November 8, 1895)

As was customary, after spending the early summer of 1895 in London preparing their previous season’s finds and socializing, Mabel and Theodore were ready for a few months’ holiday in Ireland and the north of England – during which time they would make their final plans for their next (1896) expedition.

In May 1895, Theodore had written to the governing authorities in India regarding the possibility of returning to the Yemen, ‘expressing a hope that the [India Office] would afford [him] active support in conducting surveys in the Yemen, the Hadhramaut and Mahri country…’ After due consideration Theodore was advised ‘that it would scarcely be possible … as the Turks are so sensitive about travellers in those parts….’

And that was that. Tribal unrest in the Southern Arabian lands – exacerbated by the slow decline in authority and power of Ottoman regional control and the corresponding acquisitive glances of, in particular, France, Italy and Germany – was such that even the Bents were prevented from returning for a third attempt on the Hadhramaut, in continuation of Theodore’s researches into the ‘Sabaeans’ and their influence east and west of the Red Sea: research, it is clear, that was being considered for a monograph – the traveller having produced no book since his work on Mashonaland, published in 1892.

Instead the couple settled for a short boat trip down the western coast of the Red Sea to the Sudan. As soon as the end of March 1896, the Bents were ready to return, and eventually left Alexandria (again having had their Greek assistant Manthaios Símos in attendance on this trip) to spend a few days in Athens before the journey home to London. After holidays in Ireland and the north of England, Theodore made ready to finalize their plans for the winter of 1896/7. He informs the cartographer H.R. Mill that he has been approached to explore the Horn of Africa once more:

‘My Dear Mill… Since I wrote to you last our plans for next winter are materially changed… I got a letter from the Governor of Zaila [Somalia] asking if I would undertake an expedition… this district apparently wants exploring both from geographical and political points of view and I think we shall attempt it. This will be a respectable basis on which to apply for a grant… We shall be back in London early in October when we shall meet… Yours very sincerely, J. Theodore Bent’ (Letter, 13 September 1896, (Mill Correspondence, RGS Archives: arRGS/CB7/Bent, T&M).

However the Somalia expedition came to nothing and by the late summer of 1896 the couple decided to make a further attempt at explorations in Southern Arabia, again in search of traces of the Sabaeans, and possibly reaching the western outer limits of the Hadhramaut. The routes east and north-east of Aden would trace the ancient caravan/incense trails which once, according to Ptolemy’s map of the 2nd century AD, linked Aden with Shabwa in the Hadhramaut.

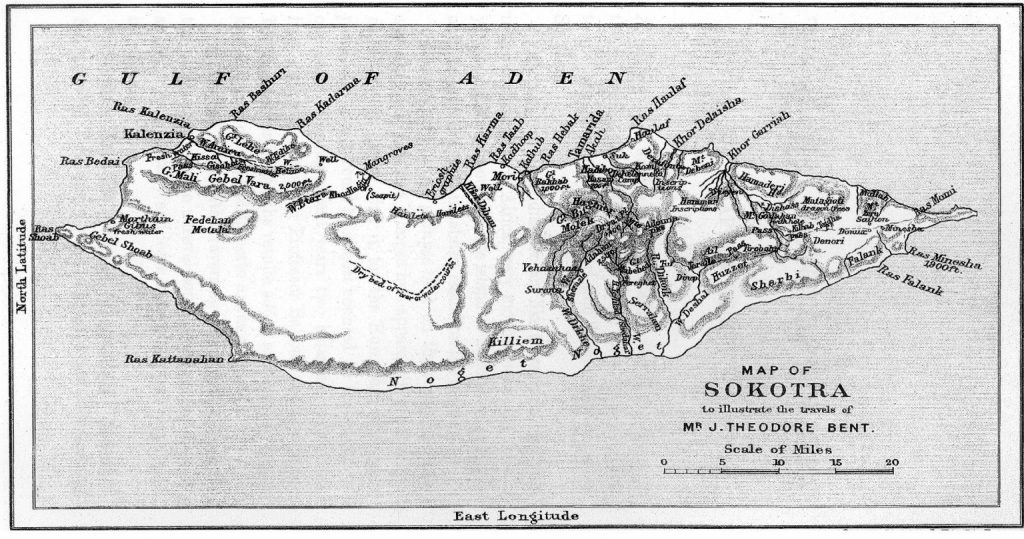

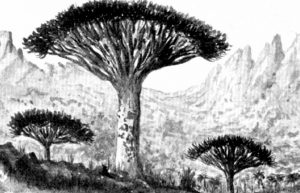

The well-worn thoroughfare led through Abyan to Bir Mighar, the territory being under the control of the Yafei and Fadli tribes, at the time relatively friendly to the British authorities. Socotra, too, lay within Theodore’s field of interest. The island was long known from early references as a land of plenty, and Theodore would have a chance to see firsthand the spectacular resin trees that were sources of frankincense and myrrh renowned in antiquity. Further objectives would include a chance at some mapping, a basic study of the distinct language, and also to look for evidence of Christianity on the island. Socotra had the added benefit of being removed from the political disturbances of the Yemeni mainland.

Ultimately Theodore was ready to issue a syndicated press release of their next (his last) expedition, even though his itinerary was obviously not settled:

‘Mr. Theodore Bent will shortly leave England for Aden, where he proposes to stay a short time before finally deciding on his winter’s field of work. In all probability he will take the first opportunity which offers itself of going to the island of Sokotra, which has now for ten years been under British protection, and is politically attached to the Aden Government. Little is known of the interior of the island; and Mr. Bent proposes to spend the winter months in exploring it, and hunting for anything that may prove of interest from an archæological point of view. As usual, Mrs. Bent will accompany her husband, and the party will also include a young Oxford man who is anxious to do some work under Mr. Bent’s experienced guidance. These winter excursions of Mr. Bent’s have now become an annual institution, and always furnish forth material for an interesting volume.’ (The Manchester Guardian, 12 December 1896)

The uncertainty of the itinerary is at odds with Mabel’s opening lines of the final section of their monograph Southern Arabia (page 343), which seems to suggest that the couple had decided in England to make Socotra the focus of their expedition for early 1897: ‘As we had been unable to penetrate into the Mahri country, though we had attempted it from three sides, we determined to visit the offshoot of the Mahri who dwell on the island of Sokotra’.

On their arrival in Aden, in contrast to their first, much larger expedition of 1893-4, Theodore was given encouragement and qualified support, but, again, with the strict proviso that he should not encroach on Ottoman interests. The explorer hurried off a progress report to the British media. halfway into their interesting editorial, confirms that Socotra was not the Bents’ first choice:

‘I learn that letters have been received in London from Mr. Theodore Bent, who arrived at Aden in the first half of this month with the intention of exploring the little-known island of Sokotra. Mr. Bent discovers that it will be very difficult for him and his party to reach the island, as the monsoon makes landing dangerous and at times impossible. But he had induced the captain of a steamer bound for Bombay to make the attempt, and if it proved unsuccessful he was going on to Bombay, where he would try to make other arrangements for reaching the island… Mr. Bent calculates that they will spend three months in making a thorough examination of the island, and three months in a traveller’s itinerary is too long to look ahead for possible difficulties, so they are not troubling themselves much as to how they are to get away. As I stated a few weeks ago [reference untraced], Mr. Bent had not absolutely decided on exploring Sokotra when he left England, but he now finds that the interior of Arabia is in such a disturbed condition that it would be hopeless for him to attempt anything in that direction, and he is, accordingly, most anxious to get to Sokotra.’ (The Manchester Guardian, 29 December 1896)

Unlike the Bents’ expedition to the Hadhramaut of 1893-4, the party to Socotra and Aden was to be a modest affair, perhaps indicating a decline in interest by the London academic and scientific communities in Theodore’s commitment to Sabaean Southern Arabia. The team included no surveyor, botanist or zoologist, the Bents taking with them a certain Ernest N. Bennett, ‘Fellow of Hertford College, Oxford’, who would be contributing to the costs, rather like the adventure-tourist of today.

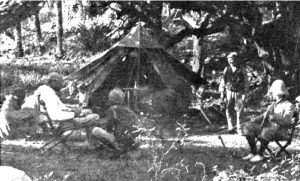

Travelling again with the Bents, for the last time, was their indispensable assistant from the Cycladic island of Anáfi, ‘Matthaios, the Greek who has travelled with us so many years’. (Manthaios – Matthew – and various other versions of his name – can be seen in Mabel’s photograph of one of their Sokotran camps reproduced here.)

It was on Anáfi, in the late 1930s, a few years after Mabel’s death, that another traveller, Vincent Clarence Scott O’Connor, had the extreme good fortune to share an after-dinner drink, his memory perhaps restored by that fine local elixir, warm rakómelo, with:

[A] wonderful Dragoman who had travelled in the remotest parts of the Earth… He proved to be one for whom I had been looking since I came to these islands; Bent’s travelling-servant… But some forty-four years had elapsed since then; and I hardly expected to meet with his servant in the flesh… In his own eyes, as was fitting, it was he and not Bent who was the central figure in all those wanderings. “He (Bent) was a very short blonde man, with blue eyes… We went to the island of Socotra with a learned man from Oxford… [We] got off at last and arrived at Aden in Arabia where no rain falls and there are camels in the streets… Mrs. Bent fell seriously ill of a fever which each day grew worse… We arrived at the sea and the Sheikh sent out some milk for the lady, but she was so ill that she could not retain it and daily she became worse… I decided then to act upon my own initiative, and a Dhow having come into the harbour, I spoke to the Captain and contracted with him to take us to Aden… It was after this that Bent himself began the illness that ended in his death… All were agreed that here was a great traveller, one like unto Odysseus himself.’ (V.C. Scott O’Connor (1929), Isles of the Aegean, 217-20)

The Bents seem to have exhausted Socotra’s secrets within eight weeks, the first of which was spent doing very little at their disembarkation point. After some difficulty and expense they succeeded in hiring a small vessel for their to return to Aden, and, finding the neighbouring tribal families relatively peaceful, decided to explore east of Aden, perhaps even contemplating the north-east route towards the Hadrami interior once more. At Aden, Ernest Bennett was eventually seen onto the steamer home, via Cairo, and the Bents, with Manthaios Símos, set out on 27 February 1897 for their last explorations together into the territories east of Aden.

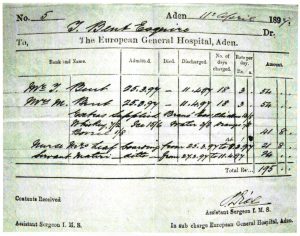

They were clearly weakened after their stay on Socotra and on March 16 Mabel records that ‘Theodore was in a raging fever so that I had to tell him I was now much better and had got quite strong, so I could take care of him.’ It was clear the expedition would have to be aborted and the arduous trek back to the coast, and onward boat journey to Aden, made as soon as possible. With great difficulty the stricken travellers were aided down to the coastal town of Shuqra for the 100-km return sail to Aden, and by 26 March were both in hospital there.

After their stay in hospital in Aden, the couple said goodbye to Manthaios (who had dysentery and was also hospitalized) for the last time and set sail for England, via Marseilles. As Mabel confides to Scott Keltie above, during the return journey Theodore had a relapse developing pneumonia on top of malaria. With the last of his strength they reached their London home (13 Great Cumberland Place) on 1 May. Despite the attentions of Mabel (and her sister Ethel), the resident doctor and two nurses, Theodore did not recover, succumbing just a few days after their final trip on 5 May 1897.

This trip that cost Theodore his life produced the least return. There were no major archaeological finds: a very few artefacts are now in the British Museum and Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. There were some plant specimens for Kew, as usual, and a few land snails are in drawers in the Natural History Museum, London.

Theodore and Mabel’s grave and memorial (right) in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Theydon Bois, Essex. Theodore’s epitaph reads: ‘Here, after his many long journeys rests J. Theodore Bent, FRGS, FSA, husband of Mabel Virginia Anna Hall-Dare, son of James and Margaret Eleanor Bent of Baildon House, Yorks. “To be with Christ which is far better”’.