Theodore and Mabel Bent along the west coast of the Red Sea: 10 December 1895 – 26 April 1896

The Bents’ short (but eventful) exploratory period through ‘Abyssinia’ in the spring of 1893 had provided Theodore with clues, inscriptions and other finds that seemed to support his theories linking early Ethiopian settlements to the Mashonaland monuments, via old trade routes that flowed east-west across the Red Sea and drove the economies of early-first-millennium societies within the southern Arabian peninsula. It was this latter region that now monopolized Theodore’s attention for the rest of his career: if Greece and the eastern Mediterranean had been his apprenticeship, Mashonaland and ‘Abyssinia’ had set him centre stage, and he now hoped his ‘Southern Arabian’ labours would see him ushered to the front of it – his chronicler, Mabel, by his side.

After lengthy discussions with the Foreign and India Offices, Theodore was eventually granted permission to embark for Aden and the Yemen in November 1893, under the strictest instructions not to conduct himself in any way that might cause an incident with the Sublime Porte.

The Bents returned to London ahead of schedule, on 20 April 1894, with Mabel recording in her Chronicle: ‘I am thankful to say the efforts of the Expedition in all branches seem to be approved of’. Certainly a pioneering exploration, their finds in the region however were modest and they failed to reach either Shabwa to the west, or to penetrate the eastern extremity of the Wadi Hadramaut (Wadi Masila). The party was forced to curtail its mission and take a shortcut to the coast and return, somewhat despondently, to Aden.

Mabel’s ‘Hadramaut’ Chronicle endeavoured to finish on an upbeat tone with: ‘and if we possibly can we’ll go back’. No doubt the couple were already planning their second expedition as they reclined in their deck chairs on the steamer back from Port Said to Marseilles. In any event they only had a few months (in between writing, researching, lecturing, and fitting in mid-summer visits to family and friends in England and Ireland) to seek backing for a second trip to the region and make all the necessary preparations. Ultimately all was ready for their (spring) 1895 campaign and a ‘press release’ was picked up by The Times:

‘Mr. Theodore Bent informs Reuter’s Agency that he and Mrs. Bent are about to start another scientific expedition to Southern Arabia… The journey being of very uncertain length, Mr. Bent’s final arrangements can only be made on reaching Muscat and ascertaining the feeling of the tribes through which country he would have to pass… Mr. Bent hopes to continue the archaeological and botanical work commenced last year, and the expedition is expected to return to England in April next.’

By early December (1894) the couple had reached Muscat. Their first objective, the immediate mountainous hinterland to the west, the notorious ‘Empty Quarter’, was considered too dangerous, so they embarked for Merbat (Mirbat), several days south-west along the coast, making for the southern district of Dhofar. From here they were to explore inland, along the old frankincense and myrrh trails, and Theodore was able to hypothesize on the locations of Ptolemy’s ‘Diana Oraculum’ and the lost coastal sites of Moscha and Abyssapolis (his musings on the latter proving to be the major discovery of this expedition).

The next phase of the journey was, somehow, to find an entry into the inner Hadramaut from the east, but their plans foundered and as soon as February 1895 (after only a few weeks’ labours) the couple were resigned to sailing for Aden, storing their equipment there, and tranship for India, where Theodore hoped he could get authorization and support (Aden falling in part under India’s purview) for a swift return to the region, but none materialized.

Within eight weeks of leaving Aden, and their subsequent short stay in India, the couple were home in London (April 1895), sorting out their collections and preparing to lecture on their findings as usual. After spending the early summer of 1895 socializing in London, Mabel and Theodore were ready for a few months’ holiday in Ireland and the north of England before making plans (they hoped) for a return to the Hadramaut region. But tribal unrest in large areas of the southern Arabian peninsular – exacerbated by the slow decline in authority and power of Ottoman regional control and the corresponding acquisitive glances of, in particular, France, Italy and Germany – was to postpone the Bents’ third attempt on the Hadramaut. The geo-political situation thus put paid to their plans and the couple had to settle for a rather ad hoc tour down the west coast of the Red Sea instead.

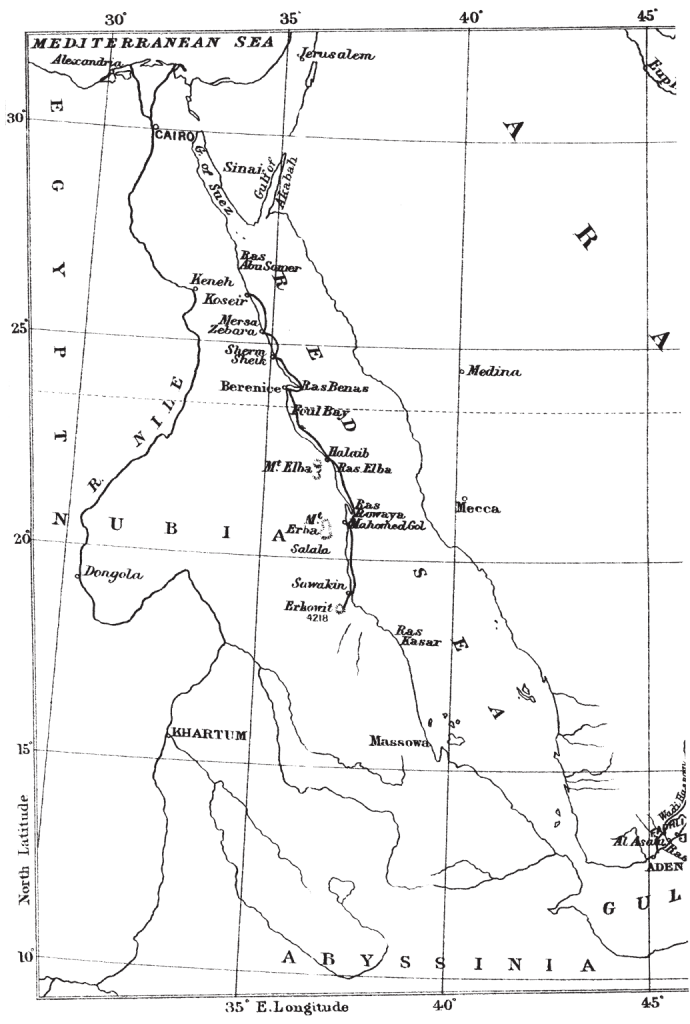

For the Bents’ 1896 (East African) expedition (in an echo of a similar and rather vague exploratory cruise the Bents made in 1886 along the coastline of western Turkey in search of chance finds) the couple decided to charter a dhow and drift south from Port Said. Having managed to assemble their gear forwarded on from Aden, where they had left it the previous season (and which included Mabel’s ‘bucket canteen, large kitchen box, empty saddlebags and large holdall, and folding stove… towels… kitchen clothes, my pith helmet and green-lined parasols also, and my hammock’), the couple could begin their leisurely boat trip down the western coast of the Red Sea along the Sudanese littoral in December 1895 with no firm objectives in mind. Theodore was content with general exploration in the hope of haphazardly uncovering evidence for early southern Arabian influence along the western shores of the ‘Erythraean Sea’: evidence perhaps with resonances of his Mashonaland (1891) and ‘Abyssinian’ (1893) discoveries.

The coast itself had a sequence of well-referenced harbours from at least the Roman era and Theodore told one of his two travelling companions, Alfred Cholmley, that his intention was ‘to explore the ruins of the ancient town of Berenice, and, if possible, to go inland from there; but if this could not be done, to coast down the Red Sea and land as circumstances permitted.’ On their eventual return, at his presentation for the RGS at Burlington Gardens on 1 June 1896, Bent spoke before the Fellows that: ‘With a view to examining the east [sic] littoral of the Red Sea, we hired a dhow at Suez, and used this as a basis of operation’. In a later article for the Nineteenth Century he put it more succinctly still: ‘This last winter we have added a few square miles to a blank corner of the map where rediscovery was necessary…’ One of the significant discoveries on this trip was the ancient site of ʿAydhab, some 20 km north of the modern port Halaib.

Theodore did seem however to have had an objective in mind, a glittering one. Since the mid-1880s Theodore relied annually on having some significant discovery from his adventures to announce back in London. Accordingly his ‘discovery’ in the Sudanese interior of Wadi Gabeit of extensive gold-mining remains (with the added bonus for him of glimpses of the faraway ruins of Great Zimbabwe, as well as tentative Greek, and indeed ‘Sabaean’, lettering) is the highlight of this 1896 expedition. There is every likelihood that Bent knew what he was looking for (although he called it ‘my new Eldorado’) and it explains his risk-taking in leaving the relative security of the coast, against the explicit orders of one of the most formidable British officers in Egypt, to find it.

In 1896 the Sudan was only a marginally safer place than the Hadramaut for Theodore and Mabel. Sitting uneasily between Ethiopia and Egypt, the region was nominally an Egyptian dependency, but the nationalist movement under the Mahdis was a constant threat to the Khedive.

The Bents were not to know, as they set off to Cairo from London (December 1895), that their government, alarmed at the unrest and the regional threat to their interests on all compass points, was planning a new British offensive – the slow vice of Kitchener’s vengeance for Gordon – a permanent end to the Dervish threat.

‘Major Wingate is doing all he can to help us in every way’, writes Mabel in all innocence from Cairo. Once again in Egypt’s capital, the Bents are soon under the watchful and amused eye of Lieutenant General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, Director Military Intelligence, Egyptian Army. After Evelyn Baring (1st Earl Cromer) and Major-General Sir H. H. Kitchener (‘Sirdar’, commander of the Egyptian army), Wingate could look back in due course over an extraordinary career in his country’s service in the region.

Despite the efforts of the two men deputed to watch over them, Theodore and Mabel, brave, if not actually reckless, refused to restrict themselves to the coastal fringes of the Red Sea (Theodore well aware that any new finds will lie below the wadi sands inland). Wingate must have been furious to have been disobeyed so, but his letter (sent as ‘private’) to his friend John Scott Keltie (also Theodore’s) at the RGS is concerned and tactful, except for one inopportune reference to Mabel:

‘The Bents are giving me some anxiety. After giving them my strict instructions not to go inland, we hear that they have done so and we have sent orders for their recall to the coast… We cannot be responsible for people who take no heed of what we say, and such action is likely to stand in the way of travellers – however I hope the Bents will turn up alright: would Mrs. B. be an acquisition, do you think, to Abdullahi’s harem?… It is possible they might come across something interesting on their travels, but it is not very probable – unless it be Dervishes. Indian affairs are at present a little complicated. Dervishes are showing a certain amount of activity on the Nile frontier…’

He is gallant enough, of course, not to embarrass the Bents when they return to Cairo to be entertained by him and his wife (who has the anxiety of her husband about to leave with Kitchener for Dongola and the Dervishes any day) at the end of their Sudanese adventures.

There were two other Englishmen sharing these adventures with the Bents. As expedition naturalist, and extra photographer, they had with them Mr Alfred John Cholmley (1845-1932) ‘of Place Newton, Rillington, Yorks’, he was a son of Sir George Strickland, 7th Baronet. The Cholmley estates near Malton in North Yorkshire were (and remain) not far from Theodore’s boyhood home outside Leeds and presumably the families were acquainted. Mabel records that Cholmley ‘had determined to accompany us’, but the squire himself notes: ‘In the autumn of 1895 I was invited by Mr. Theodore Bent to join him in an expedition to the west coast of the Red Sea…’ By all accounts a responsible and well-liked landlord (with over 5000 acres in his care and in 1890 restoring the village school), Alfred was a lepidopterist and ornithologist of the old school, not much being safe from his gun and skinning-board: the ‘reddish-brown Sand-Partridge’ he bagged was named after him Ammoperdix cholmleyi.

“Movements of Ornithologists.—We are pleased to hear that Mr. Theodore Bent will take a naturalist with him during his new expedition this winter. He has arranged that Mr. A. J. Cholmley shall accompany him, but he is going, not to Dhofar, we are sorry to say, but to the country on the Red Sea south of Suakim. This district has been already well worked by Heuglin, Jesse, Blanford, and others, but there are sure to be a lot of crumbs left, which an observant collector will pick up.” (The Ibis, Vol.II. Seventh Series, 1896, p.157)

The other figure Wingate seconded to the Bent expedition of 1896 was more to Mabel’s taste – the dashing and soon-to-be distinguished soldier, Nevill Maskelyne Smyth of the Queen’s Bays (1868-1941). She writes that ‘Mr. Nevill Smyth, Queen’s Bays, wished to come and has got leave’, but it is more likely that he drew a short straw. From an established service family (first cousin to Robert Baden-Powell and an admiral’s grandson), Smyth was smart, trustworthy, brave, and commissioned by Wingate with the twin tasks of producing a good map and keeping his eyes open; on at least one occasion Mabel writes that he takes off into the hills to reconnoitre, looking far westward towards the Dongola reaches, where he was soon to fight in the campaigns of that summer of 1896.

Completing the party, the Bents had asked their old friend and assistant from Anáfi, Manthaios Símos, to join them at Port Said by mid-December, meeting his travel expenses as usual. Alfred Cholmley is to thank for the only published reference to his surname; Mabel and Theodore never mention it once in fifteen years of travels with him on and off: ‘Our party consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent, Lieut. Smyth of the Queen’s Bays, and myself; Mouthes [sic] Simos, a Greek, as cook…’

Once the fellowship had disbanded, and they were on their way back to London in April 1896 after a short stay in Athens, Theodore and Mabel had to face up to the fact that the Sudanese expedition had not revealed much to science. Apart from his observations on the goldmines of the Wadi Gabeit, the recorded inventory of items (as identified in Mabel’s diaries or Theodore’s articles, or in museum catalogues) brought back to London is the leanest of any from their travels. Unusually, Mabel makes no reference to the British Museum in her Chronicle, suggesting that they were not officially collecting – that is to say they had no purchasing budget from the institution. A few years before her death some of Mabel’s personal Sudanese artefacts were presented to the Museum, all of the acquisition numbers including the prefix ‘Af1926’ denoting the year they were received. These included a few personal (modern) ornaments and a few sherds and stone container fragments. Had the Bents stopped to explore Myos Hormos, or even discovered Ptolemais Theron, then their finds might have been extensive.

Back in London in the summer of 1896, Theodore, with his customary rapidity, wrote the papers and articles that were descriptive of their trip, as usual using Mabel’s Chronicle for reference. (His own Sudanese notebook – one of only four that seem to have survived – remains with his wife’s in the archives of the Joint Library of the Hellenic and Roman Societies at Senate House, London.) In order of scale and scope, his publications consisted of a short piece on the slave-trade (ironic in that some of Mabel’s father’s wealth came from the disposal of family estates in British Guyana), a well-written and fast-paced article for a popular magazine, and his major account for the RGS. This latter included many photographs, most of them taken by Alfred Cholmley, who was the main expedition photographer for once – Mabel usually fulfilled this role, and still took her cameras with her.

Bent’s reports of gold working along the Sudan coast attracted much media interest, as might be expected. Newspaper accounts of his finds could be read as far away as New Zealand.

The presentation that Theodore gave to the RGS on 1 June 1896 included a wonderful sequence of thirty-six glass lantern-slides, four of which are reproduced in this volume. They are miraculous survivors. Theodore made good use of the modern technology at his disposal and we know that four sets of his lantern-slides were kept until February 1951, at which date three of them were destroyed as they had ‘faded’. It is a sad loss of course (today they could have been treated), but by good fortune twenty-two of the original thirty-six glass slides that Theodore had prepared for his Sudan talk have survived and are rare things in the RGS archive. They are unique and include the only images of Mabel herself on expedition, as well as scenes of campsites, landscapes, antiquities, their assistant Manthaios Símos, and even ‘Draka’, their long-suffering pet dog that we are about to meet. So many of Mabel’s photographs, and Theodore’s sketches, now being lost, to have just these few slides safe is a unique resource.

Of interest is an oblique reference we have to the above RGS performance that appears in the diary pages of another great couple of travellers, the Blunts. It is always nice to find alternative perspectives. The Blunts, like Theodore and Mabel Bent, were also in thrall to the Middle East. The Red Sea littoral, a region, then, as now, is not without its great dangers. Does Wilfred, perhaps, exhibit a little Bent envy?

“1st June [1896]: Went up to London to take Anne [i.e. wife,] to a Geographical meeting, where Theodore Bent gave some account of his travels south of where we were last winter [i.e. the Upper Nile]. Like all our geographers nowadays he is an arch Jingo, and talked of opening up the country by gold digging as if it would be a work of piety. The Geographical Society has lent itself to this sort of thing in Africa for the last thirty years.” (My diaries; being a personal narrative of events, 1888-1914, by Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, New York, 1922, p. 230).

Concluding the literature, after his death and in her tribute volume to her husband – Southern Arabia (1900) – Mabel incorporated large extracts from Theodore’s articles, and many verbatim passages from her Chronicle, into a chapter in this still-popular work entitled ‘An African Interlude, The Eastern Soudan’.

See also the excellent ‘Desert Networks’ coverage of the Bents’ 1895/6 trip from Suez to Suakin.