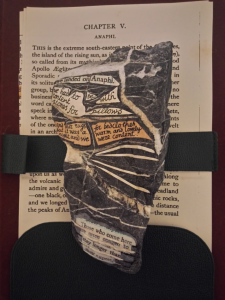

The fourth in Professor Margaret Kenna’s Theodore and Mabel Bent-related series of ‘incidentals’ covering the Cycladic island of Anáfi, centres around a well-known landmark you can easily find on the way to Kastelli, the hill on which the Hellenistic city ruins can be found. Thus Margaret’s third short ‘talk’ in her thyme-scented series is called: ‘“The sarcophagus” at the Bents’ time, earlier, and more recently’.

Margaret is a retired social anthropologist from Swansea University who has been carrying out research on Anáfi, and among Anáfiot migrants in Athens, since 1966. She has written two books and many articles in English about her research: Greek Island Life: Fieldwork on Anafi (2nd edition 2017, Sean Kingston Publishing), and The Social Organisation of Exile: Greek Political Dissidents in the 1930s (2001, Routledge). A Greek translation of the second book was published in 2004 by Alexandreia Press. Many of her articles, in English and in Greek translation, can be found on the websites: academia.edu and ResearchGate. She has also written several booklets which can be found in tourist shops on the island: Anafi: a Brief Guide; Anafi: Island of Exile; The Folklore and Traditions of Anafi, and The Traditional Embroideries of Anafi. She was made an Honorary Citizen of the island in 2006.

ανάφηανάφηανάφηανάφη

“The sarcophagus” at the Bents’ time, earlier, and more recently

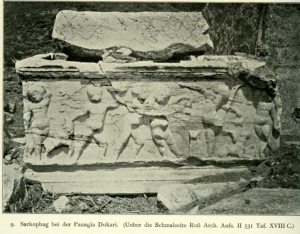

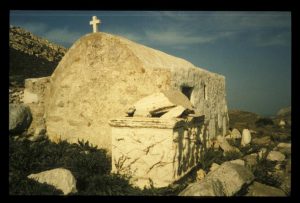

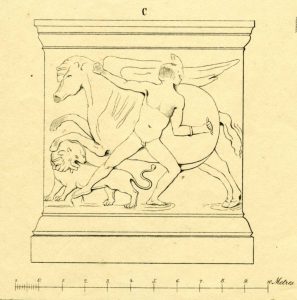

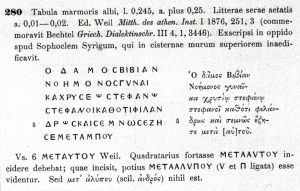

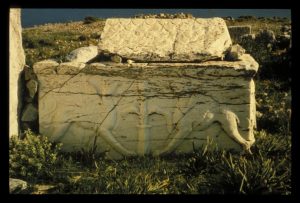

“On the way to Kastelli, the hill on which the Hellenistic city ruins can be found, the Bents came to ‘a little church’ (the chapel of Panayia tou Dokari), next to which is a marble sarcophagus. As Bent records, there is on one side, ‘a beautifully executed representation of children bringing sacrifices to Bacchus…. On the other side are Bellerophon and Pegasus, and on the two narrow sides are Sphinxes.’ (Bent 1885: 47). Actually, not quite correct, as these photos will show…..

Figure 1: The sarcophagus outside the chapel of Panayia tou Dokari in summer 1967 – Sphinx on short side (east-facing), jolly cherubs on long side (south-facing) (M. Kenna).

Figure 1: The sarcophagus outside the chapel of Panayia tou Dokari in summer 1967 – Sphinx on short side (east-facing), jolly cherubs on long side (south-facing) (M. Kenna).

Figure 2: The jolly cherubs in late afternoon sunshine (M. Kenna).

Figure 2: The jolly cherubs in late afternoon sunshine (M. Kenna).

Figure 3: Hiller von Gaertringen’s photo of the jolly cherubs, 1898 (IG XII/3).

Figure 4: In summer 1973, Bellerophon and Pegasus on short side (west-facing), jolly cherubs still jolly (M. Kenna).

Figure 5: Bellerophon and Pegasus in late afternoon sunshine (M. Kenna).

Figure 6:…easier to see in Ross’s early C19 drawing of the west-facing side of the sarcophagus (Ross 1840-1852).

Figure 7: Not a sphinx, but winged griffins either side of a pillar, on the north-facing side (M. Kenna).

Figure 7: Not a sphinx, but winged griffins either side of a pillar, on the north-facing side (M. Kenna).

“Oh, well, the Bents were walking in the January rain, so maybe Theodore can be forgiven for confusing sphinxes and griffins…

“Another sarcophagus was probably in the same location, as fragments of the decorated ‘roof’ can be found built into the wall of the chapel. Bent writes that this other one ‘appears to have been even richer in execution’ (Bent 1885:47).

Figure 8: Fragment of the roof of ‘the other sarcophagus’ (to the right of the headless statue), built into the chapel wall, spring 1967 (M. Kenna).

Figure 8: Fragment of the roof of ‘the other sarcophagus’ (to the right of the headless statue), built into the chapel wall, spring 1967 (M. Kenna).

“There is a sarcophagus (Figure 8) of a similar type in the National Archaeological Museum found in Patras in the Peloponnese, dated around 150 A.D./ C.E., which gives an idea of what the Anafi sarcophagus might have looked like. The scene depicted is a boar hunt.

Figure 9: Item 1186, National Archaeological Museum, Athens (M. Kenna).

Figure 9: Item 1186, National Archaeological Museum, Athens (M. Kenna).

“But go see for yourself! Let’s hope all this tempts you to get out from underneath the tamarisks of Roúkouna this summer and stroll Kastelli-wards to snap it. Wear your hat tho!”

References

Bent, Mabel and Brisch, Gerald (ed.) 2006. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Vol I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Bent, Theodore 1885 (2002). The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Hiller von Gaertringen, F. 1898. Inscriptiones: IG XII/3.

Ross, Ludwig 1840-1852. Reisen auf den griechischen Inseln des ägäischen Meeres (1840-45). Stuttgart, Tübingen, Cotta.

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article