The sound of the tsabouna, or the Greek bagpipe.

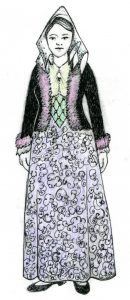

The strains of music from this instrument would have been very familiar to Theodore and Mabel as they journeyed from island to island. At the time of their travels, the tsabouna (sometimes sambouna and various spellings) was still one of the most popular folk instruments for the islanders. Its prominence probably linked to some degree with the goats and sheep the islanders were raising.

Every part of the animal was used. The milk was used to produce the delicious mizithra cheese enjoyed by the Bents, while the meat formed the key element of many local dishes that we still enjoy today – even the entrails were used for the ubiquitous dish, kokoretsi, and the Easter soup, magiritsa. The wool and hide, of course, found many uses.

Maybe somebody, hundreds, or even thousands, of years ago, scratched their head searching for other uses for the goat’s inedible skin. With a gurgling, a squealing and a wailing, the tsabouna was born.

Theodore was never too adoring of the melancholy sound of the instrument. ‘that wretched Grecian substitute for the bagpipe’ he wrote on Anafi, and in Karpathos he describes it as ‘a species of bagpipe, being a goatskin with the hairs left on, which palpitates like a living body when filled with air. These instruments are romantic enough when played by shepherds on the hillside or in the village square as an accompaniment to the dance, but they are intolerable in the tiny cottages where women tread their flannel.’

Despite his apparent dislike for the tsabouna, one does wonder whether he really had a sneaking admiration for it. While in Karpathos, he acquired his own tsabouna and brought it back to England where, after his death, it eventually found its way to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Mabel has left quick note of the instrument as they heard it in Olymbos, Greek Easter time 1885: “We then went all together to a ball in the outer room of the church. We sat in a heap of people in the middle and round the edge sat mothers, each with a babe and a string of men screwed round in the narrow space left, preceded by the sampouna, pronounced sambouna, or bagpipe…” (From Mabel Bent’s Greek Chronicles, Vol 1, 2006, page 105)

Did Theodore ever learn to play this wretched Grecian substitute for a bagpipe – we’ll never know – but it would be nice to think he at least tried!

During the 20th century the tsabouna’s popularity faded and it’s only in recent years that a small number of traditional musicians has embraced the instrument and is bringing about its revival. One of these musicians is Yannis Pantazis who crafts his own instruments and demonstrates them in his artisan workshop in Santorini. Yannis is an outstandingly versatile musician who fell in love with the tsabouna on first hearing before he even knew what it looked like. Ever since, he has devoted his life’s work to the plaintive-sounding Greek bagpipe and the other instruments in his collection such as the lyre, the panpipes and the flute as well as traditional percussion instruments. Pop in and see him if you’re in Santorini – you will undoubtedly end up ‘gigging’ with him as he demonstrates and enthusiastically talks about the history and mythology attached to each instrument.

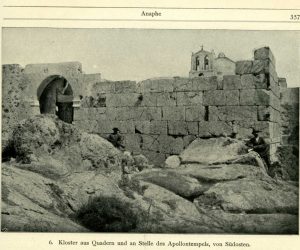

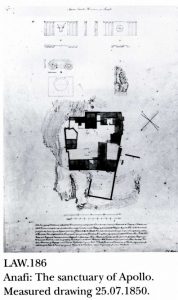

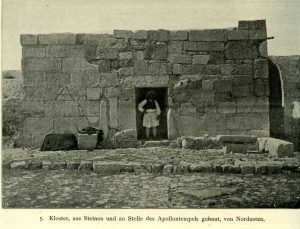

There’s a final twist in this tale of Theodore and the tsabouna. On the 11th January 1884, he and Mabel came ashore in the south of Santorini having travelled by sail-boat from the neighbouring island of Anafi. They landed near the small church of Aghios Nikolaos, ‘a little white thing under a red rock’ wrote Mabel. Taking a rough track, after some difficulties, they finally reached the hill-top village of Akrotiri just before dusk. Eating only what they’d carried from Anafi, they slept the night in the tower of the Venetian castle.

That very tower, known as La Ponta, was the first workshop of Yannis Pantazis where he constructed and played the instrument seemingly both loved and abhorred by Theodore. Yannis had never heard of the Bents but he believes Theodore’s accounts of the tsabouna are some of the earliest records we have in modern times of the playing of the instrument.

La Ponta has cast a powerful spell over the course of the past 130 years, bringing into its orbit, two key figures, generations apart – one who experienced and documented the popularity of the tsabouna in its heyday, the other spearheading the vanguard of the renaissance of the instrument today.

One hopes Theodore would have approved! (A paperback edition of his ‘Cyclades‘ is available from Archaeopress, Oxford)

Discover more about Yannis Pantazis, his workshop and performance space

SYMPOSION by La Ponta Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/symposionsantorini

SYMPOSION website at https://www.symposionsantorini.com

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article