PLEASE be aware that the following article by Theodore Bent transcribed here contains references and descriptions from the start reflecting the attitudes and language of the time that we find offensive and unacceptable today. The article, nevertheless, is a little-known and important addition to Bent’s bibliography, as much as possible of which we aim to make available to those interested in 19th-century travel and exploration.

Bent’s article “An Excavator’s Camp” [Great Zimbabwe] appeared in the Pall Mall Budget (Christmas Edition, No. 1264), of Thursday, 15 December 1892. The periodical was an illustrated, up-scale, general-interest weekly mainly for the British establishment, and well reflecting this milieu; its cover price was 6d, c. £7.50 today. The Bents, as celebrity-explorers, often featured on its pages.

The excavator’s theories on the Great Zimbabwe ruins were, of course, controversial and now generally disproved. Bent himself was unsure at first as to what date to put on the monuments but by 1892, the time of this article, for various reasons and pressures, he was publishing that they were very early, perhaps even dating from his perception of ‘Phoenician’ times, and were not built by local populations. His interpretation led to 100 years of controversy over the ruins – it also made Theodore and Mabel Bent the celebrity explorers of the decade.

§ § §

WHEN MY WIFE AND I started on our excavating trip to the Zimbabwe ruins in the centre of Mashonaland we thought we were about to enter upon the most hazardous undertaking of our lives; we had dug in Persia, Arabia, Asia Minor, and Greece; we had braved the dangers of Kourdish brigands and Turkish officials; but we had never as yet encountered naked black men, about whom scarcely anybody knew anything. When we made our preparatory wills the thought of Matabele impis, war dances, deadly fevers, snakes, lions, and tsetse flies flitted before our eyes, but now that it is all over, and we are safe home again with our treasure trove, we smile at our former fears, wonder where the lions came from which seem to have molested other people’s journeys who never left the beaten track, and recommend a trip to Mashonaland to all our friends. note 1

Our camp at Zimbabwe was in the heart of the wilderness, some fifteen miles from the up-country road; on all the neighbouring peaks were Mashona villages, where the timid inhabitants had built their huts to be out of the way of Matabele raids; every day crowds of them came to see us and sell us food, and Umgabe, the great, fat naked chief who rules over this district, professed to love us dearly. This was all very different to what we had expected; hunters and traders had told us of the superstitious awe with which the natives guarded the massive ruins, of the hairbreadth escapes they had had in viewing them and in carrying off a few stones, but fat old Umgabe grinned at us complacently, and gave us permission to do exactly what we liked with them, on one condition, and that was that we should leave his women alone. These dusky daughters of Africa have evidently, like many of their fairer sisters, a tendency to over-rate their charms; they avoided us at first, deputing the withered hags to bring their commodities to exchange for beads and cloth; but by degrees we inspired confidence, and daily we were invaded by the naked ladies with stomachs decorated with lines or cicatures like furrows, beads and bangles round their legs and arms, and a simple loin cloth round their waists, their personal attractions being very much on a par with those of the female monkeys at the Zoo.

Umgabe had a younger brother called Ikomo, who governs the small village on the hill amongst the ruins, and from his close proximity to our camp we saw a good deal more of him than we wanted; if he could, he prevented our work. On more than one occasion he succeeded in frightening our Mashona workmen from other villages away. He was always begging for something – generally for salt, the rarest and most prized commodity in these parts, large lumps of which he would put into his mouth, and suck as complacently as we might a chocolate cream. He would instantly introduce his unsavoury body into our tent, and surreptitiously insert his unsavoury fingers into our honey-pot, thereby obliging us to throw away what he left; he was undoubtedly the thorn in our existence at Zimbabwe, and one day he nearly succeeded in bringing about an open rupture between us and our natives.

This occurred when we were engaged in excavating on the hill, and our work led us to prosecute a trench beneath a certain boulder rock, on the top of which was erected one of the mud granaries in which they store their grain. Suddenly the boulder slipped, to the infinite peril of the men who were engaged beneath it; down came the granary with its contents of grain and “monkey” nuts, and we had hardly recovered from the shock, and were congratulating ourselves on our escape, when up rushed Ikomo in a towering rage, followed by all the villagers; women shrieked, men brandished assegais, and the affair looked as it it would become serious.

I called together all our men from outlying posts. I seized an assegai myself, which chanced to be lying near: each man stuck tight to his spade, his pick, or his crowbar, and quietly we awaited events. It was in vain that we attempted a parley, and gave Ikomo to understand that what damage had been done should be made good. The screams of fury grew louder and louder, until one of Ikomo’s men gave the signal of battle by suddenly falling on one of our black workmen from a neighbouring village, knocking him to the ground. Consequently in self-defence we had to retaliate, for had we maintained our quiet demeanour our turn to be knocked down would doubtless have come next, so we rushed as hard as we could on the black mass of humanity opposed to us, belabouring them with our weapons to the right and to the left. Never was a British victory more easily won. Almost before we touched them the enemy fled, and an odd flight it was, and no mistake. They clambered like cats up the granite boulders, keeping up a perpetual jabber all the time, just as monkeys do in their cage when more than usually perturbed in their shallow minds. Ikomo himself retired sullenly to his hut, and that evening was summoned to our camp for a palaver, where, before an officer of the Chartered Company, he was solemnly told that is such a event occurred again his village would be burnt, his cattle confiscated, and Zimbabwe Hill would know him no more, and, under the circumstances, nothing would be paid for the damage we had done. Thus ended our one and only conflict with the natives. note 2

Living as we did for two months near this village during our work, we naturally became familiar with all its features. Whenever there was a beer-drink, a dance, or a funeral, we had special facilities for witnessing the same; and on all these occasions the Mashonas do dance with a vengeance: for hours together they will revolve in a monotonous circle to the tune of the everlasting tomtom and their metal-keyed piano; now and again they indulge in the more energetic war-dance, when assegais and spears are brandished, scouts will be sent out to reconnoitre imaginary enemies, and so fierce do they look on these occasions that had it not been for our previous knowledge of their cowardice we might almost have quaked for our own safety.

Women dance, too, by themselves; they occasionally enjoy a frenzied war-dance immensely, but they are apt to get too excited, and either end in hurting themselves or going into hysterics, and these Amazonian orgies generally come to an untimely conclusion. The women are best at a peaceful, rather sensuous dance of their own, in which they smack their furrowed stomachs and long hanging breasts with their hands in measured cadence with their feet: the noise they manage to make in so doing is most surprising.

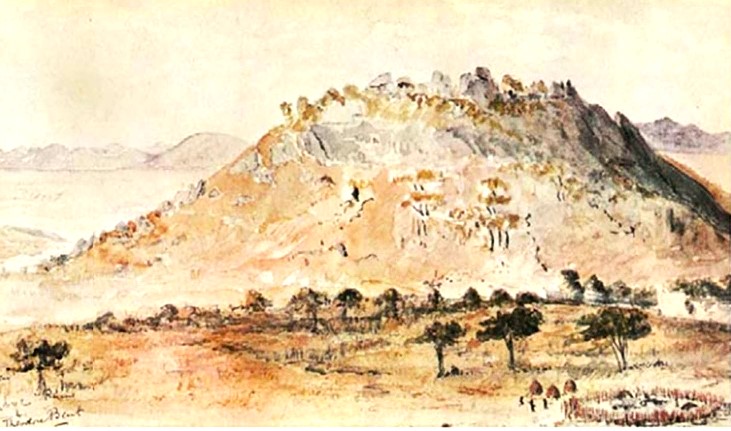

Zimbabwe village is a lovely spot, high above the swampy, feverish plain. The views from it are simply exquisite over the rich blue granite mountains and wooded, park-like, undulating country. The daub huts are hidden, like birds’ nests in a tree, among the rugged granite boulders; festoons of bignonia were rich with flowers when we were there; fiery-coloured aloes appeared in splendid masses on the rocks, and from the trees in the village hung long pendants, like magnified sausages, in which the natives kept their stores, tying them up tightly with grass until required for consumption: in these they store sweet potatoes, ground nuts, caterpillars, and other dainties in which they rejoice; on either side are the great storejars for grain, made of mud; in the centre is the fire, and around in the smoky rafters they hang their wooden pillows, their assegais, their bows and arrows, their musical instruments, and their pipes, having no other form of cupboard known to them, and rats career around.

Our camp was unfortunately on the plain below, for it was impossible to drag our waggons up the hill, and in our waggons we slept and kept all our things. On either side of us were swamps, consequently during our stay at Zimbabwe our most formidable enemy was fever. We had fourteen cases in all, and every morning, when well enough myself I had to trot round with the quinine bottle and examine my patients’ tongues. When these were not to my liking I administered a simple emetic consisting of salt and mustard mixed in warm water into the consistency of a thick soup. This was generally effective; but on one memorable occasion the horrible concoction stayed down, and, agreeing capitally, settled the patient’s stomach, and no more was heard of it. Our cook’s favourite remedy was an onion porridge, a dish so loathsome in its consistency that the sick dreaded it more than the fever. Whenever there was a wet day – and we had nine drizzling days of Scotch mist during our stay at Zimbabwe – new cases of fever were sure to present themselves, so that in the end only two of our whites escaped scot-free – one was a burly Englishman, the other was my wife. note 3

Around our camp was huge, wavy grass, towering high above our heads, in many places twelve or thirteen feet. This, it proved, was dangerous, for when ripe the rain and the sun combined in rotting it. It was not till we had been five weeks encamped there that it was dry enough to burn, and in a rash moment we set fire to it not far from our camp, with the result that for an hour or two we were in mortal dread that we and everything that belonged to us would be consumed in the flames. On they came, roaring, hissing, crackling; in vain we arranged an army of beaters to try and ward off the enemy, more formidable than any force Ikomo or Umgabe himself could muster. Soon all the grass huts which our native workmen had erected for themselves were ablaze; our grass hedge or “skerm”, which we had erected around our camp, was torn down in hot haste, and we discussed in hurried tones what we should save and what we should abandon. Luckily this terrible sacrifice in the midst of a wilderness was not required of us. The enemy was vanquished just in time. Our poor Mashonas had to shiver in a cave that night, and we had to do without our hedge. This was all the material damage we suffered, and for the rest of our stay at Zimbabwe we had much less fever, though instead of a picturesque cornfield around us our camp might have been pitched on the edge of a coal pit.

Our camp was very picturesque in its way; and “Indian terrace”, as our men called it, was constructed of grass and served as a dining-room. Our waggons were our bedrooms and our tents our drawing-rooms; and our white men built apartments for themselves within the hedge. Every morning at eight o’clock an improvised gong, consisting of a hammer and a waggon wheel-tire, assembled our men. Every evening at sunset we returned home to our well-earned dinner. Around the camp fires nearly every night our men sang all the latest music-hall ditties, which came fast and furious when a consignment of “dop” (as that rank poison Cape Brandy is called up country) came from Fort Victoria. Luckily, as yet, the Mashonas know not the potency of fire-water; they only get mildly muddled with their own porridge-like beer. May they long remain thus innocent! We ourselves generally passed the evening in discussing our work, speculating on our finds, and building up castles in the air for the morrow. note 4

I can hardly conceive of a more exciting life than that of an excavator’s, especially when he is brought face to face with a prehistoric mystery like Zimbabwe. Searching after gold and hunting after wild beasts seems sordid and tame to my mind in comparison to the intense delight of relics of a bygone and utterly forgotten race of mankind; and when that race lived in the centre of the dark, mysterious continent, themselves a gold-searching race, long centuries ago, no element is wanting to add to the keenness of the sport.

When the time for our departure drew nigh, we packed our curios in the waggons for their long journey to the Cape note 5 , and, bidding adieu to comforts – that is to say, of a comparative nature – we mounted our horses and loaded a donkey with our necessaries, and set off for an independent trip among the neighbouring villages or kraals, for we wished to acquaint ourselves with the life of the Mashonas at home, and thought that a few nights in their huts and in the centre of their villages would be the most satisfactory way of attaining this object. A Mashona sleeps naked on a grass mat, with his head resting on a carved wooden pillow, so we could hardly depend on them for bed-clothes. A Mashona lives chiefly on millet meal porridge, caterpillars, mice, and other vermin, so we could hardly depend on them for food. Consequently our requirements were such that our donkey had to be supplemented with two or three native bearers.

We honoured Umgabe first with a visit. note 6 His kraal lies in a valley, a perfect paradise of verdure, about six miles from Zimbabwe; the potentate himself had been indulging freely in beer before we arrived, and looked fatter and more sodden than ever; still, he managed to gather himself together, and received us graciously enough in his round mud palace.

Umgabe at home is a curious sight; he sat on the floor at one end of his almost stifling hut, his indunas sat on either side of him. After the customary hand-clapping had been gone through, a ceremony indulged in at every meeting amongst them, the inevitable bowl of beer was brought in. The chief’s wives make it, and the head wife brings it in on bended knee, first tasting it herself, to prove that she had introduced no poison therein. Then Umgabe drank, then each induna had a sip, and by the time our turn came it was almost impossible to find a clean corner from which to drink. These are the occasions on which it is absolutely fatal to think; if once we had allowed ourselves to dwell on the dirty hands which had stirred it, and the revolting ingredients which gave it a flavour, I fear me we should rarely have been polite; for it is a great breach of savage etiquette to refuse to drink on these festive occasions.

We wanted very much to see a celebrated cave near Umgabe’s kraal, where the natives take refuge in time of danger. This cave had been formed by the stream, which runs down the valley, eating its way through a mass of granite boulders. The approach to it is difficult to find, and the labyrinthine intricacies of the interior are most remarkable. Umgabe flatly refused to show us the way, neither would he allow any of his men to do so, and was exceedingly angry with us for wishing to explore his tribal secret. Nothing daunted, we wandered about till we found it, and penetrated into its recesses with the aid of candles. Inside, it is full of granaries, where they store their grain and broken pots, and when the Matabele threaten them they somehow manage to drive their cattle in too, and so intricate are its passages that no enemy could ever approach them, and beneath them they have the boiling stream with an ever-flowing supply of water.

Poor Umgabe has often been raided by the Matabele, for his village is low and very fertile. We annexed here an admirable servant called Mashah, who stayed with us on our journeyings for some weeks. He had been captured, together with his father, his mother, and his wife, who was a sister of Umgabe’s, by the Matabele, and had been a slave for many years; his father and his mother died in captivity, but he and his wife had contrived to escape. He is an excellent fellow, perfectly indefatigable; he effects European costume – that is to say, a hat with an ostrich feather in it, and an old shirt, but nothing more. We gave him an old pair of trousers, but after he and all his friends tried them on and found them uncomfortable he tied them as a mantle round his neck. We gave another man an old pair of boots, but he only annexed the brass tags to make himself a necklace of, and threw the leather away.

Umgabe gave us for our night’s lodging what looked externally an ideal residence beneath a shady cork-tree but oh ! the horrors of those rats which careered over us during those nights in the native huts, and the persistency of those cocks and hens; which never would take any hint to absent themselves. We did not live long enough in native huts to get accustomed to these intruders. For the rest of our journeyings in Mashonaland, we, like the children of Israel, got us to our tents. note 7

Notes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4

Return from Note 5

Return from Note 6

Return from Note 7

By way of Bibliography

Bent published many articles on the couple’s epic adventures in Southern Africa – they are available via our Bibliography (starting from 1891). See especially:

J. Theodore Bent, The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland (Longmans, London, 1892) – Bent’s bestseller by far, containing maps, plans, his sketches, Mabel Bent’s photographs, etc.

Mabel Bent, The Travel Chronicles of Mrs. J. Theodore Bent, Vol. 2, The African Journeys (Archaeopress, Oxford, 2012, pp. 17ff.) – an edition of Mabel Bent’s diaries recording Great Zimbabwe, from the Archive of the Hellenic Society (kept at Univ. London, Senate House). Facsimiles of Mabel Bent’s originals are available at:

1891: My Eighth chronicle: to Zimbabye in Mashonaland (Vol. 1)

1891: My Eighth chronicle: to Zimbabye in Mashonaland (Vol. 2)