Researches throw up Bent bits all the time – some don’t make it into articles or into our main pages. Nevertheless they are interesting (we think) and might perhaps be useful to some in their studies of mid-19th century travellers and their times.

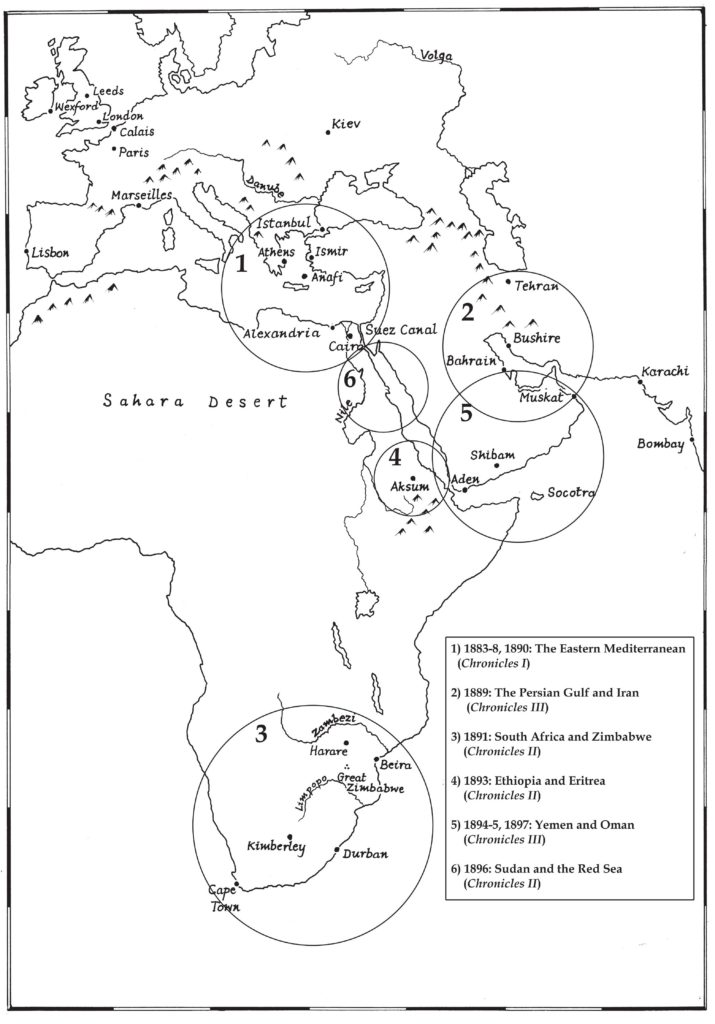

After all, Theodore and Mabel were partial to the odd sidetrack (look at the map) and this Bent Miscellany might well lead you down some…

Snippets are added regularly, latest first, so return as often as you like. We include references and links wherever possible and if you want to cite www.tambent.com that would be appreciated.

Updated October 2025

Professor Ahmad Al-Jallad is conducting fascinating work (2025) on the Dhofari script – the conventional name for the undeciphered alphabet found in the hills of Dhofar (Ẓufār) and desert regions, stretching from Oman to Yemen’s al-Mahrah governorate and Socotra, where the Bents recorded several inscriptions.

The Paddington Times, Friday 2 August 1895: “Yet women are under a sex disqualification when a poor little squabble among men arises, whether or not one of them, like Mrs. Theodore Bent, the wife of the distinguished traveller of Mashonaland, who has done the work of a dozen explorers, has friends who expect that her additions to the scientific knowledge of the day will be acknowledged as they would be if she were of the other sex.”

The Paddington Times, Friday 16 September 1898: “The British Association this year met at Bristol for the third time, and has just concluded its business… In every section room last week ladies formed the majority of the audience. They were not of the butterfly class, rushing from place to place in search of novelty, but serious students from college classrooms and laboratories, who had travelled long distances to see and hear the great authorities of the scientific world. Many of the girls were themselves teachers, and keenly interested in scientific research. The papers by ladies were few in number, but noteworthy. The three great lady travellers of our time came to the front, modest, self-contained, accurate, and enthusiastic, each in her own domain – Mrs. Bishop, Mrs. Bent, and Miss Kingsley.”

Mid-Surrey Times, Saturday 15 May 1897: “Mr. Bent was always accompanied by his wife, one of whose functions was to look after the commissariat. Mr. Bent was a thorough believer in tea on his travels, and did not advise anyone to explore on spirits. The larder of the travellers usually included desiccated soups, corned beef and beef essence, potted meats, condensed milk, and, last but not least, some sackfuls of dry bread, for long experience taught Mr. and Mrs. Bent both what to avoid and what to add to there travelling impediments.”

From The Youth’s Companion, v. 81, no. 26, June 27, 1907, pages 307-308

In the article ‘The Real “King Solomon’s Mines”, by H. Rider Haggard’: ‘These ruins [Great Zimbabwe], in spite of certain late theories to the contrary, it would seem almost certain, – or so, at lease, my late friend, Theodore Bent, and other learned persons have concluded,- were built by people of Semitic race, perhaps Phoenicians, or, to be more accurate, South Arabian Himyarites, a people rendered somewhat obscure by age. At any rate, they worshiped the sun, the moon, the planets, and took observations of the more distant stars.’

From The Youth’s Companion, v. 82, no. 20, 14 May 1908, page 235

‘Afraid of safety-pins. It is not easy to realize the bondage to fear under which barbarous people live on account of their superstitious ignorance. Mrs. Theodore Bent tells in her book, “Southern Arabia”, how she tried to make a present of a safety-pin to a native woman, and what a storm of indignation was occasioned by her act. On our arrival at our camping-ground and while we were waiting for our tents to be ready, I was surrounded by women all masked. They seemed highly astonished at a safety-pin which I was taking out, so I gave, or rather offered it, to an old woman near me. She wanted to take the pin, but several men rushed between us and roared at us both, and prevented my giving it to her. I stood there holding it out and she stretching out her hand, and one or two men then asked me for it for her. I put it down on a stone, and she took it away and seemed pleased; but a man soon brought it back to me on the end of a stick, saying they did know these things and were afraid of them.’ (credit: Digital Library@Villanova University)

From The Youth’s Companion, v. 98, no. 52, December 25, 1924, page 852

in ‘Fireflies by J. Renwick Metheny’. ‘It does not pay robbers to get themselves or their horses shot. Like men of other occupations, they want to lose nothing. It is not from cowardice but from prudence that they resort to stratagem. Osman Oghlu, of whom Theodore Bent wrote so fascinatingly, fought with reckless courage against an overwhelming force of armed men; and at that he had no chance of escape… (credit: Digital Library@Villanova University)

From The Youth’s Companion, v. 71, no. 41, October 14, 1897, page 477

In ‘The Breath of Allah in Six Chapters, Chapter 1’ by Charles Asbury Stephens (1844-1931). ‘”The English at Aden call it the Valley of the Hadramut”, replied the young engineer. “It lies eighty or a hundred miles inland from the barren south coast of Arabia, which stretches easterly from the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb to the Persian Gulf. In the days of King Solomon in the long centuries of the Roman Empire, the Vale of Hadramut was known as the country from which frankincense was brought, but since the era of Mohammed little has been heard of it. The fanaticism of the Moslem seyyids shut it up from the world till the year 1893, when an English traveler and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Bent, succeeded in so far winning the confidence of the sultans, or Arab princes, as to be permitted to enter the vale and reside there for a time.”‘ (credit: Digital Library@Villanova University)

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article