James Theodore Bent came into the world on March 30th 1852 at 20 Bedford Street South in Liverpool and was baptized in St Philip’s Church (then in Hardman Street near the city centre) on April 28th. His uncle, Sir John Bent (1793-1857) was Lord Mayor in 1850/1.

The book to recommend on the wider history of the family is The Bent family in America. Being mainly a genealogy of the descendants of John Bent who settled in Sudbury, Mass., in 1638, with notes upon the family in England and elsewhere… by Allen H. Bent (1900, Boston).

A distant relation was the British novelist Nathaniel ‘Nat’ Gould (1857-1919), whose forebears married into the Bent family. A website on him provides further background information.

By the 17th century, the Bents of Bentlanes, near Manchester, were a family of note. Names remembered single out Laurence Bent (d.1670), his son Hamlet, and his son Laurence (d.1775). This Lawrence had a son John (d.1796), who married Anne Hill and they reared several children, two of whom established dynasties: James Justin Bent (1739-1812; physicians) and William Bent (1764-1820; potters and brewers). These men were Theodore Bent’s great-uncle and grandfather respectively. James Justin, his estate at Basford Hall, near Newcastle-under-Lyme, was the renowned surgeon who amputated Josiah Wedgewood’s leg in 1768.

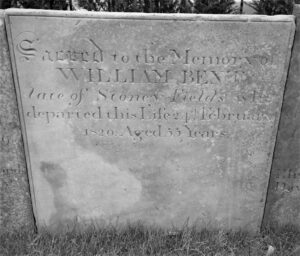

The family fortunes, however, stemmed in the main from Bent’s grandfather, William, born in 1764 at Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire, the son of John Bent (1717-1796), the family living at ‘Stoneyfields’ on King Street in Newcastle from 1801. Sometime in the 1790s, William started a pottery business in Newcastle that he soon transformed into a dynamic brewery concern that operated, ultimately, from four plants – Newcastle-under-Lyme, Shrewsbury, Macclesfield, and Liverpool, managed generally by William’s four sons, including for a while Theodore Bent’s father, James (1807-1876). In various guises, and despite several changes in fortune, Bent’s Breweries continued into the 1970s. Its founder died relatively young (55) in 1820, and William was buried in St Giles’, Newcastle-under-Lyme, where his headstone (below) can still be found. His wife, Theodore Bent’s paternal grandmother, was Sarah Gorton of Salford; they married on 31 July 1792 at Manchester Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral).

Theodore Bent’s mother was Margaret Eleanor (c. 1811-1873), of the wealthy Baildon Lamberts, and the young Bent spent his early years at the family home – the modestly grand Baildon House, near Bradford in Yorkshire in the north of England. As referred to above, the family was very comfortably off, and the young James had a privileged upbringing.

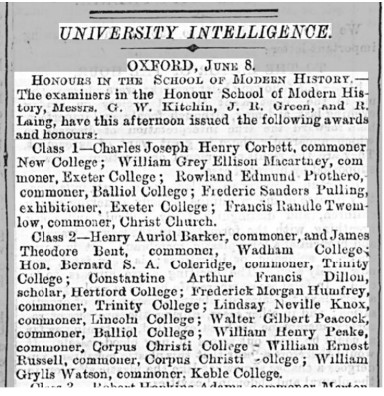

After his preparatory school (taken to be May Place, Malvern Wells, Worcestershire, attending from c. 1863-65), he went to Repton public school (in Derbyshire, slightly nearer to home; he appears there on the 1871 Census (Sunday, 2 April), aged 19, p.o.b Liverpool, 1852), and from there to Wadham College, Oxford (c. 1873-75), where he graduated with a BA (a Second) in Modern History, taking the Oxford MA later (matriculated 8 June 1871, aged 19, B.A. 1875 [‘Oxford University Alumni’, 1500-1886, Vol.1]).

As for first impressions, The Times of 7 May 1897 refers in Bent’s obituary to his “wide circle of friends, to whom his kindly, genial, unaffected disposition had greatly endeared him.” But the first impression he gave to his waggonmaster when trekking to Great Zimbabwe in February 1891 comes as rather a shock (but in the end they got on very well): “The following day Mr Bent the archaeologist and his wife and companion… arrived by train from Capetown and I met them at the railway station and was introduced to them. I was disappointed in Mr Bent who seemed to be stand-offish and at the same time he did not impress me as being by any means a clever man. He had no presence and I was so disappointed that for two pins I would have declined to go with him. However, after a little thought I decided to carry on as I had given up my situation with the Orion D. M. Company and would not perhaps be able to get another job in Kimberley.” (‘Llewellyn Cambria Meredith (1866-1942), quoted in R.H. Wood, Heritage of Zimbabwe 16(1997): pp. 55-66)

In the 1918 book The Making of Modern Yorkshire, 1750-1914 (London: G. Allen & Unwin), we read (pp. 295-8) more of Bent’s contemporary status, finding him in the company of one of Shackleton’s great men: “Of the many illustrious Yorkshiremen – and women – of the nineteenth century it is only possible to mention a few of the more distinguished amongst artists, musicians, novelists, poets, scientists, scholars, statesmen, and travellers… [Two] Yorkshiremen have in recent times achieved great distinction in the world of travel. James Theodore Bent, 1852-1897, a Leeds man, explored Arabia, Abyssinia, and the ruined cities of Mashonaland; Douglas Mawson, born in Bradford, 1882, has already made himself famous the world over by his intrepidity as a three-times explorer of the Antarctic Regions.”

Among the many institutions Bent was associated with, four stand out: (1) he was a prominent member of the Hellenic Society, joining in 1883 – in 1885 he was member of the Council, remaining as such until his death in 1897; (2) he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries on 1 July 1886, having been recommended on 1 August 1885, officially proposed on 19 November, and balloted on 1 July 1886. Among the great and the good supporting Bent were Percy Gardner, Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge, and the titan, Thomas Spratt; (3) he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society on 16 June 1890 (having been proposed on 12 May 1890, just a few months before the Bents set off to investigate the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, part-sponsored by the RGS); (4) he was elected Member of the Anthropological Institute at its meeting on 21 June 1892 (see, Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, v.22, 1893, p. 174), very much the result of his ‘triumph’ in Mashonaland. He was also a member of the Folk-law Society until his death.

In terms of politics, we may safely assume both the Bents, husband and wife, were establishment conservatives. We know Mabel, an active member of the Primrose League, was. The Paddington Times of Friday, 20 July 1906 records: “Lord and Lady Ludlow’s Garden Party – One of the most brilliant and enjoyable social functions that has taken place in Marylebone for many years past was held on Monday afternoon [16 July 1906], when, to celebrate the recent return of two Conservative members to Parliament for Marylebone [i.e. Robert Cecil and Sir Samuel Scott], Lord and Lady Ludlow gave a large party at the Botanical Gardens, Regent’s Park, to the members and friends of the Constitutional Union, of which his Lordship ably fills the position of Chairman.” Mabel Bent appears in the list of guests.

Good family trees of the Bents and Hall-Dares are available to subscribers of Ancestry.

Good family trees of the Bents and Hall-Dares are available to subscribers of Ancestry.

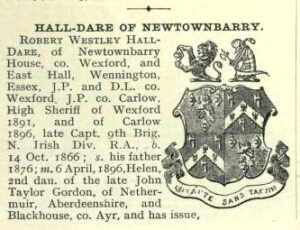

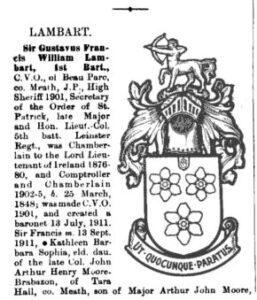

Bent’s remarkable wife, Mabel Virginia Anna Hall-Dare was born at Beauparc House, County Meath in Ireland on January 28th 1847. note 1 The daughter of Robert Westley Hall-Dare (1817-1866) and Frances Catherine Anna Lambart (d. 1862); she was descended from a line of Anglo-Irish aristocracy with strong, historic ties on her father’s side to the county of Essex, just outside London. Via her mother, Frances Anna Catherine Lambart, Mabel descends from “Oliver Lambart, 1st Lord Lambart, Baron of Cavan (died June 1618) was a military commander and an MP in the Irish House of Commons. He was Governor of Connaught in 1601. He was invested as a Privy Counsellor (Ireland) in 1603. He was also an English MP, for Southampton 1597. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.” (Wikipedia, accessed 24/4/2025)

The British Association this year [1898] met at Bristol for the third time, and has just concluded its business… The three great lady travellers of our time came to the front, modest, self-contained, accurate, and enthusiastic, each in her own domain – Mrs. Bishop, Mrs. Bent, and Miss Kingsley.” (The Paddington Times – Friday 16 September 1898)

Mabel must have inherited her mettle from her forebears. Her great-great-grandfather was Lord Mayor of London in 1743 and her great-grandfather, Robert Westley Hall, was a planter in Guyana. Mabel’s father had relocated to Ireland from Essex sometime before Mabel’s birth and had established the family seat at Newtownbarry House in Co. Wexford (following a period in Sligo at Temple House). An interesting overview of the family is presented in Arthur Kavanagh’s booklet – Hall-Dare & Harvey of County Wexford (The Wexford Gentry), 2015.

Mabel is described as being ‘Five feet eight inches tall, a green-eyed, sturdy redhead – striking in her photographs – her flaming, plaited hair was often the subject of native wonder. Outgoing and confident, she was as happy taking fences at full gallop in her native Wexford as she was dining with British ambassadors in Cairo or Constantinople.’

We do not know how the couple chanced upon each other (they were in fact very distant cousins via the Lambarts) but Mabel has told us that they met in Norway, probably in the early 1870s. Theodore and Mabel married on August 2nd 1877. Both of independent financial means, and after honeymooning in Norway, they soon embarked upon their travels, most winters seeing them leave their home in London, embarking for extended tours abroad (more often than not, via Dover-Calais, a train to Marseilles, then a ship to the Eastern Mediterranean, and beyond….).

Their first trips were to Italy and in 1879 Theodore published a book on the republic of San Marino entitled A Freak of Freedom: Or, the Republic of San Marino. In recognition of his work, Theodore and Mabel were made honorary citizens of San Marino. In 1880 he published Genoa: How the Republic Rose and Fell, followed in 1882 by The Life of Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Their journeys around the Cyclades followed between 1883 and 1885 and the very successful book The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks was published in 1885. In the succeeding years they continued exploring the more easterly islands of the Aegean Sea, many of which were then Turkish, as well as the Aegean coast of Turkey.

Click for descriptions of Mabel’s travel attire.

1889 saw the couple exploring the Bahrain islands of the Persian Gulf, their journey home comprising a ride, south-north, through Persia. Their famous trip in 1891 to Africa was the basis for Theodore’s next best-seller, The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland, published in 1892. Ethiopia followed with the resulting book, The Sacred City of the Ethiopians, being published in 1893. During their final years of travel, Theodore and Mabel concentrated on the southern Arabian Peninsula and the African coast of the Red Sea.

It was on the island of Socotra, in the Gulf of Aden, that Theodore contracted the malaria that was to bring about his premature death. They managed to get back home to London but Theodore died four days later on May 5th 1897 at the age of just 45. Mabel buried her hero near her ancestral home at St. Mary the Virgin Church, in Theydon Bois, Essex.

The London Daily News of August 21st 1897 reports on Bent’s will, revealing the sum of £21,497 and giving details of his assets and beneficiaries.

Of the many many obituaries and fond recollections of the man, several are now provided below. Of all the thousands of words, three, by Sir James Knowles, Bent’s friend and editor, seem to say it all – ‘delightful and adventurous’ (‘The Island of Socotra’. The Nineteenth Century, Vol. 41 (244) (June 1897), p. 975).

E.W. Bradbrook, president of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, recalled Theodore in his anniversary address of 11 January 1898, saying (and Mabel would have been in the audience most probably) “In the death of Mr. J. Theodore Bent, the Institute has to deplore the early termination of a life of remarkable achievement and high promise. An intrepid explorer and a ripe scholar, Mr. Bent was also a man of singularly attractive and engaging character…” (The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Vol. 27 (1898), pp. 552-553).

The great Superintendent of Frontier Surveys in British India, Colonel Sir Thomas H. Holdich, K.C.I.E., C.B., R.E., was a good acquaintance of Bent’s, who travelled to India to consult him on Yemeni matters. Holdich gave a short but moving tribute in an address to the Royal Geographical Society: “ Theodore Bent has left the fields of Arabia and Africa; Elias will no more tread the steppes of Central Asia…” (Holdich, T. (1901). Advances in Asia and Imperial Consolidation in India. The Geographical Journal, 17(3), 240-250).

The Royal Geographical Society’s obituary at the time is a full one, and again stresses Bent’s good nature (he was elected an RGS Fellow on 16 June 1890): “Mr. Bent’s kindly and genial nature had endeared him to a wide circle of friends, by whom his loss will be keenly felt…” (The Geographical Journal. v.9 1897 Jan-Jun. pages 670-1 and reprinted in The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia: Monomotapae Imperium by R.N. Hall and W.G. Neal, pages 11-12, London, 1902).

Mabel was involved in the scandal of women RGS Fellows in the early 1890s, her name being on the list for the second tranche, but women were abruptly banned for standing as Fellows again until 1913. The experience may well have something to do with the fact that Mabel decided to leave her notebooks not to the RGS but to the Hellenic Society (of which she was a member, joining in 1885 and remaining affiliated for over 30 years, resigning in 1918).

Theodore was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries on 1 July 1886. In their magazine they pick up on his popularity with the general public: “Readers of the Antiquary will have heard with much regret of the death of Mr. J. Theodore Bent, F.S.A. Mr Bent… was both an explorer and an antiquary, and he was one of those fortunate persons whose writings at once caught the ear of the public… Had Mr. Bent’s life been spared to a longer period, there is no doubt that he might have hoped to take a fairly high place in the niche of fame.” (Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past, 1896, page 165).

Mabel never really recovered from the loss of her constant partner, her travel companion and her raison d’être. She did make more journeys abroad after Theodore’s death but found her first one to Egypt ‘lonely’ and ‘useless’! With great strength she completed the book that Theodore had started, recounting their final journey; Southern Arabia was published in 1900. In 1904 she published A Patience Pocket Book and in 1908 Anglo-Saxons from Palestine: or, the Imperial mystery of the lost tribes.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, Mabel’s name appears fairly regularly on passenger lists to Palestine. As we might well expect of her, she was still travelling well into her 70s. The Great War was still fresh in the memory when she again resumed her trips to Jerusalem and the Holy Land; in April 1920 she boarded the Union Castle’s Grantully Castle at Port Said for London Docks. And on December 30, 1921, she embarked on the P.&O. Delta at London Docks for Port Said once more. Always keen on a little PR, Mabel frequently sent out ‘press releases’ and gave interviews, particularly when she was about to leave for, or return from the Holy Land:

“A Lady Explorer – Mrs. Theodore Bent left London last week [December 1907] for Jerusalem, where she purposes remaining until next March. There are probably few women who have travelled more in known and unknown parts of the world than Mrs. Bent, who, in her late husband’s lifetime, made archaeological and exploring journeys in the Cyclades, Sporades, Asia Minor, Persia, Mashonaland, Abyssinia, Hadramut, Dhofar, the Island of Sokotra, the Eastern Soudan, Beled Fadhli, and Beled Yafei, in South Arabia. She is an honorary citizeness of the Republic of San Marino – a probably unprecedented honour – and assisted Mr. Bent in deciphering the mysteries of the Zimbabwe ruins.

“Mrs. Bent during her wanderings up and down the earth, must have seen many lovely landscapes, but probably none to surpass that with which she was familiar as a child in Newtownbarry. By birth she was a Miss Hall-Dare, of Newtownbarry, and the home of the Hall-Dares, on the banks of the Slaney, is one of the most beautiful in that part of Ireland; it lies close to the foot of Mount Leinster. The Hall-Dares, however, are an Essex family, their connection with this English county going back over 200 years. It was in the year of Waterloo that Elizabeth Dare married Robert Hall, High Sheriff of Essex, and for some years M.P. for South Essex, who took by royal sign manual the surname and arms of Dare, in addition to those of Hall. Mrs. Bent’s mother was a Lambart of Beauparc, co. Meath, so that there is plenty of Irish blood in her veins, which probably accounts to some extent for her intense love of wandering.” (St. James’s Budget, Friday 20 December 1907, page 9)

Southern Arabia (published 1900)

The preface, and the final words, of her great work and in many ways her legacy, Southern Arabia, paint a poignant picture of Mabel’s profound grief and sadness at losing Theodore:

If my fellow-traveller had lived, he intended to have put together in book form such information as we had gathered about Southern Arabia. Now, as he died four days after our return from our last journey there, I have had to undertake the task myself. It has been very sad to me, but I have been helped by knowing that, however imperfect this book may be, what is written here will surely be a help to those who, by following in our footsteps, will be able to get beyond them, and to whom I so heartily wish success and a Happy Home-coming, the best wish a traveller may have.

The book’s final two sentences read:

This is all I can write about this journey. It would have been better told, but that I only am left to tell it.

Dying at the age of 83 on July 3rd 1929, Mabel was buried alongside Theodore at Theydon Bois. She and Theodore never had children and she never remarried. She spent the last 32 years of her life alone, perhaps living up to the motto on her family coat-of-arms – ‘Loyauté sans tache’ – ‘Unsullied loyalty’.

An entry from the Probate Register records that Mabel left £12,228-8s-10d in her will.

A review of Mabel’s book Southern Arabia provides a happy paean: “The vivacity of her feminine humour, the keen observation of amusing little details, the lively recollection of droll anecdotes, and the brave wife’s spirit of comradeship in their frequent adventurous travels, grace with a peculiar charm the instructive revelation of much rare fresh learning which concerns the lore of historic antiquity, as well as the present condition of territories yet imperfectly known… That lady’s courage and high spirit, the tact and cleverness with which she managed to bear her position as the only female traveller, must have been a great help to her conjugal partner. This book is her memorial of him, acceptable to many readers who condole with her irreparable bereavement.” (The Illustrated London News, April 21, 1900, p. 556)

And those who think the Bents must have been sitting on Greek beaches all day, or rolling down sand dunes, need to think again. Their work ethic was quite extraordinary, even unparallelled perhaps for a duo over a period of twenty years: knowing every summer that they would be repeating their amazing efforts the following season, and this before any of the real comforts or securities of 20th-century travel. Hypothetical job-descriptions/CVs for them would have to specify deep interests in archaeology, ethnology, anthropology, botany, natural history; plus demonstrations of skills and traits such as: temperance, fitness, strength, courage, perseverance, sense of humour, administration, logistics and finance, mapping, research, historical knowledge, note-taking, publishing, drawing, photography, camping, cooking, first-aid, sailing, riding (including camels), public relations and self-promotion, basic knowledge of firearms, man management (from the Shah of Persia to the peasant in the field), and anything else that day-to-day travel in the Levant, Africa, or Arabia, in all weathers, might require.

Read more about the Bents’ extraordinary lives:

- The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks

- World Enough, and Time: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I: Greece and the Levantine Littoral

- Make Our Sun Stand Still: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent. Volume II: The African Journeys

- Deserts of Vast Eternity: The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent: III: Southern Arabia and Persia

- The Dodecanese: Further Travels Among the Insular Greeks: Selected Writings of J. Theodore & Mabel V.A. Bent, 1885-1888

For the background to the extended Hall-Dare family (in 1912), see Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (1912, London, pp. 165-6. Mabel is listed as the second daughter of Robert Westley Hall-Dare, marrying Theodore Bent in August 1877.

For the background to the extended Hall-Dare family (in 1912), see Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (1912, London, pp. 165-6. Mabel is listed as the second daughter of Robert Westley Hall-Dare, marrying Theodore Bent in August 1877.

For Mabel’s family, the Lambarts of Beauparc, Co. Meath, see Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage (1914, London, pp.1151-2).

For Mabel’s family, the Lambarts of Beauparc, Co. Meath, see Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage (1914, London, pp.1151-2).

Return from Note 1