The Bents at Easter in Amorgos – 1883

It seems Theodore Bent visited Cycladic Amorgos, briefly, twice, once for Orthodox Easter in 1883 (April 28 – 1 May, Old Style) and then again in February the following year. Mrs Bent presumably joined her husband for the first visit (although Mabel does not make this clear), after they had been to Tinos for the “great pilgrimage on the Greek March 29th, that is in the beginning of our April 1883”. There are no first-hand accounts of Amorgos in Mabel’s Chronicles, but she makes clear in her 1884 diary that “During the last week of my stay [on Antiparos], T went to Amorgos. I was not well and remained for further rest. I joined [him] on the steamer Eptanisos at Paroikia on Ash Wednesday, February 27th, after having waited a day and a night as the weather was stormy”. Theodore chose to end his great book on the Cyclades (1885) with an account of these two visits, suggesting how much he/they enjoyed this lovely and fascinating island that acts as a stepping stone between the distinct styles of the Cyclades and the Dodecanese.

Bent’s Amorgos chapter in The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks is well known and can be easily found freely on line. Less well known is the article he wrote first for Macmillan’s Magazine, Easter Week in Amorgos (1884, Vol. 50 (May/Oct), 194-201; reprinted in Littell’s Living Age, Vol. 162 (1884), 402ff), and on which he generously based his chapter, no doubt supplementing the latter with material from his second visit (a Cycladic figurine he acquired there is in the British Museum). Thus a longish, edited, extract from the Macmillan’s piece follows, and will, we trust, entertain and perhaps inspire an Easter visit next year!

(For the mystery of whether Mabel accompanied Theodore to Amorgos on his first visit in 1883, see the article Amorgos Amigos.)

Before reading on – why not get in the mood with the video of the Amorgos ceremonies in a closely associated site linked to our editors!

EASTER WEEK IN AMORGOS – J. Theodore Bent

“This, the remotest island of the Cycladic group, and the bulwark, so to speak, of the modern Greek kingdom, would well repay a visit at any other time than Easter week, for its quaint costumes and customs, and unadulterated simplicity; but Easter week is the great festival of Amorgos, and is unlike Easter in other parts of Greece, for the Amorgiotes at this time devote themselves to religious services and observances, which now scandalise the more advanced lights of the Hellenic Church, and greatly annoy the liberal-minded Methodios, Archbishop of Syra, in whose diocese Amorgos is situated, and who cannot bear the prophetic source for which this island is celebrated, and would stop it if he dared; but popular feeling, and the priests, who gain thereby, prevent him.

“The steamer now touches here once a week a dangerous enemy, indeed, to these primaeval customs, but pleasanter than a caique so we availed ourselves of it, and carried with us a letter of introduction to the Demarch of Amorgos from the head functionary in these parts, the Nomarch of the Cyclades. It is seldom calm between Amorgos and her neighbours; the full force of the Icarian sea runs into a narrow channel which separates her from some smaller islands. This fact, again, prior to the advent of the steamer, tended to keep the Amorgiotes to themselves.

“The first object which struck us was the costume of the elderly women; that wretched steamer has brought in western fashion now, so that the younger women scorn their ancestral dress, but the old crones still seem to totter and stagger beneath the weight of their traditional headgear. There is a soft cushion on the top of the head, a foot high at least, covered with a dark handkerchief, and bound over the forehead with a yellow one; behind the head is another cushion, over which the dark handkerchief hangs half way down the back, and the yellow handkerchief is brought tightly over the mouth so as to leave only the nose projecting, and is then bound round so as to support the hindermost cushion. This complicated erection rejoices in the name of ‘tourlos’, and is hideously grotesque, except when the old women go to the wells, and come back with huge amphorae full of water poised on the top of it, plying their distaffs busily the while, totally unconcerned about the weight on their heads. Naturally a head-dress such as this is not easy to change, and the old women rarely move it until their heads itch too violently from the vermin they have collected within. We only saw the rest of the old Amorgiote costume on a feast day; with the exception of the ‘tourlos’, the silks and brocades of olden days are abandoned in ordinary life.

“The demarch received us rather gruffly at first; he was busy with the weekly post which had arrived by our steamer. He distributes the letters, there being no postman in the island. But when his labours were over he regaled us with the usual Greek hospitality, with coffee, sweetmeats, and raki, and then prepared to lay out a programme for our enjoyment. ‘Papa Demetrios’, said he, ” is the only man who knows anything about Amorgos.” So the said priest was forthwith summoned, and intrusted with the charge of showing me the lions of Amorgos. ‘We had better visit the points of archaeological interest first’, said he. ‘Next week we shall be too busy with the festival to devote much time to them.’ So accordingly the three next days were occupied in visits to remote parts of the island, old sites of towns, old towers and inscriptions, whilst the world was preparing for the Easter feast.

“I do not propose to narrate the usual routine of a Greek Easter, the breaking of the long fast, the elaborately decorated lambs to be slaughtered for the meal, the nocturnal services, and the friendly greetings of these everybody knows enough; but I shall confine myself to what is peculiar to Amorgos, and open my narrative on a lovely Easter morning, when all the world were in their festival attire ready to participate in the first day’s programme.

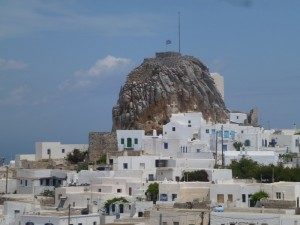

“First of all I must take the reader to visit a convent dedicated to the Life-Saving Virgin (Chozobiotissa), the wonder of Amorgos. It is the wealthiest convent in Greece next to Megaspelaion, having all the richest lands in Amorgos and the neighbouring islands, besides possessions in Crete, in the Turkish islands, and elsewhere. The position chosen for this convent is most extraordinary. A long line of cliff, about two miles from the town, runs sheer down 1,000 feet into the sea; a narrow road, or ledge, along the coast leads along this cliff to the convent, which is built half way up. Nothing but the outer wall is visible as you approach. The church and cells are made inside the rock. This convent was founded by the Byzantine emperor, Alexius Comnenus, whose picture existed until lately, but they suffer here frequently from rocks which fall from above, one of which fell not long ago and broke into the apse of the church and destroyed the picture of the emperor.

“We entered by a drawbridge, with fortifications against pirates, and were shown into the reception room, where the superior, a brother of the member for Santorin, met us, and conducted us to the cells in the rock above, to the large storehouses below, and to the narrow church, with its five magnificent silver pictures, three of which were to be the object of such extraordinary veneration during Easter week. The position of this convent is truly awful. From the balconies one looks deep down into the sea, and overhead towers the red rock, blackened for some distance by the smoke of the convent fires; here and there are dotted holes in the rock where hermits used to dwell in almost inaccessible eyries. It is, geographically speaking, the natural frontier of Greece. Not twenty miles off we could see from the balcony the Turkish islands, and beyond them the coast of Asia Minor. Our friendly monks looked too sleepy and inert to think of suicide, otherwise every advantage would here be within their reach.

“Three of the five silver eikona in this church were to be the object of our veneration for seven days to come. One adorns a portrait of the Madonna herself, found, they say, by some sailors in the sea below, and is beautifully embossed and decorated with silver; one of St. George Balsaniitis, the patron saint of the prophetic source of Amorgos; and the other is an iron cross set in silver, and found, they say, on the heights of Mount Krytelos, a desolate mountain to the north of Amorgos, only visited by peasants, who go there to cut down the prickly evergreen oak which covers it as fodder for their mules.

“We were up and about early on Easter morning, the clanging of bells, and the bustle beneath our windows made it impossible to sleep. Papa Demetrios came in dressed exceedingly smartly in his best canonicals, to give us the Easter greeting. Even the demarch and his wife were more genial and gay. At nine o’clock we and all the world started forth on our pilgrimage to meet the holy eikons from the convent. The place of meeting was only a quarter of a mile from the town, at the top of the steep cliff, and here all the inhabitants of the island from the villages far and near were assembled to do reverence.

“I was puzzled as to what could be the meaning of three round circles like threshing floors, left empty in the midst of the assemblage. All round were spread gay rugs and carpets, and rich brocades; every one seemed subdued by a sort of reverential awe. Papa Demetrios and two other chosen priests, together with their acolytes, set forth along the narrow road to the convent to fetch the eikons, for no monk is allowed to participate in this great ceremony. They must stop in their cells and pray; it would never do for them to be contaminated by the pomps and vanities of so gay a throng. So at the convent door, year after year at Easter time, the superior hands over to the three priests the three precious eikons, to be worshipped for a week.

“A standard led the way, the iron cross on a staff followed, the two eikons came next, and as they wended their way by the narrow path along the sea the priests and their acolytes chanted montonous music of praise. The crowd was now in breathless excitement as they were seen to approach, and as the three treasures were set up in the three threshing floors everybody prostrated himself on his carpet and worshipped. It was the great panegyric of Amorgos, and of the 5,000 inhabitants of the island not one who was able to come was absent. It was an impressive sight to look upon. Steep mountains on either side, below at a giddy depth the blue sea, and all around the fanatical islanders were lying prostrate in prayer, wrought to the highest pitch of religious fanaticism. Amidst the firing of guns and ringing of bells the eikons were then conveyed into the town to the Church of Christ, a convent and church belonging to the monks of Chozobiotissa, and kept in readiness for them when business or dissipation summoned them to leave their cave retreat. Here vespers were sung in the presence of a crowded audience, and the first event of the feast was over. Elsewhere in Greece on Easter day dancing would naturally ensue, but out of reverence to their guests no festivities are allowed of a frivolous nature, and every one walks to and fro with a religious awe upon him.

“Monday dawned fair and bright as days always do about Easter time in Greece. Again the bustle and the clanging of bells awoke us early. There was a liturgy at the Church of Christ where the eikons were, and after that a priest was despatched in all hurry up to the summit of Mount Elias, which towers some 2,000 feet above the town. Here there is a small chapel dedicated to the prophet, and this was now prepared for the reception of the eikons by the priest and his men, and tables were spread with food and wine to regale such faithful as could climb so far. Meanwhile we watched what was going on below in the town, and saw the processions form, and the eikons go and pay their respects to other shrines prior to commencing their arduous ascent up Mount Elias. It was curious to watch the progress up the rugged slopes, the standard-bearer in front, the eikons and priests behind, chanting hard all the time with lungs of iron. Not so my friend the demarch, with whom I walked. His portly frame felt serious inconvenience from such violent exercise, so we sat for a while on a stone, and he related to me how in times of drought these eikons would be borrowed from the convent to make a similar ascent to the summit of Mount Elias to pray for rain, and how the peasants would follow in crowds to kneel and pray before the shrine.

“It is strange how closely the prophet Elias of the Christian Greek ritual corresponds to Apollo, the sun god of old; the name Elias and Helios doubtless suggested the idea, just as now St. Artemidos in some parts has the attributes of Artemis. When it thunders they say Prophet Elias is driving in his chariot in pursuit of dragons, he can send rain when he likes, like Zeus of ancient mythology, and his temples, like those of Phoebus Apollo, are invariably set on high, and visited with great reverence in times of drought or deluge.

“After the liturgy on Mount Elias the somewhat tired priests partook of the refreshments prepared for them, for Phoebus Apollo was very hot to-day, and the eikons were heavy, and my host, the demarch, enjoyed himself vastly, for his pious effort was over, and the descent was simple to him. All the unenergetic world was waiting below, but we who had been to the top felt immensely superior, and Papa Demetrios gaily chaffed the lazy ones on the way to vespers in the metropolitan church for their lack of religious zeal. Here the eikons spent the second night of their absence from home. I was very curious about the next day’s proceedings, for on Tuesday the eikons were to visit the once celebrated church of St. George Balsamitis, where is the prophetic source of Amorgos. So I left the town early with a view to studying this spot, and if possible to open the oracle for myself before the crowd and the eikons should arrive. It is a wild walk along a narrow mountain ridge to the Church of St. George, about two miles from the town. Here I found Papa Anatolios, who has charge of this prophetic stream, very busily engaged in preparing for his guests. A repast for twenty was being laid out in the refectory, and he said a great deal about being too much occupied when I told him I wished to consult his oracle.

“On entering the narthex Papa Anatolios still demurred much about opening the oracle for me, fearing that I intended to scoff; but at length I prevailed upon him, and he put on his chasuble and went hurriedly through the liturgy to St. George before the altar. After this he took a tumbler, which he asked me carefully to inspect, and on my expressing my satisfaction as to its cleanness he proceeded to unlock a little chapel on the right side of the narthex with mysterious gratings all round, and adorned inside and out with frescoes of the Byzantine school. Here was the sacred stream which flows into a marble basin, carefully kept clean with a sponge at hand for the purpose lest any extraneous matter should by chance get in. Thereupon he filled the tumbler and went to examine its contents in the sun’s rays with a microscope that he might read my destiny. He then returned to the steps of the altar and solemnly delivered his oracle. The priests of St. George have numerous unwritten rules, which they hand down from one to the other, and which guide them in delivering their answers. Papa Anatolios told me many of them. These and many other points Papa Anatolios told me, and I thanked him for letting me off so mercifully. To my surprise on offering him a remuneration for opening to me the oracle he flatly refused and seemed indignant.

“About midday we heard the distant chanting of the procession, and soon the three eikons and their bearers were upon us. After the liturgy was over and the religious visit paid, we had a very jolly party in the refectory. Papa Anatolios produced the best products of the island lambs, kids, fresh curdled cheese, wines, and fruits and it was not till late in the afternoon that we started on our homeward route, still chanting and still worshipping these strange silver pictures from the convent.

“We were all rather tired that evening on our return from the oracle, so next morning the bells failed to wake us early, and I was glad to learn that the eikons had started on a visit to a distant place where I had already been, Torlaki, where is an old round Hellenic tower; so during the early part of the day I strolled quietly about the town. I was strong enough that evening to walk down to the sea-shore to see the arrival there of the eikons, with their wonted accompaniment of chanting and festivity. The little harbour village was decked with flags, the caiques and brigs were also adorned, and a good deal of firing was going on in honour of the event.

“That night the eikons and I passed by the harbour certainly to my personal discomfort, for never in the course of my wanderings did I rest under a dirtier roof than that of Papa Manoulas. He is a proverbial Greek priest, having a family of eleven children; he keeps a sort of wineshop restaurant for sailors, and excused the dirtiness of his table by saying that men had been drunk in his house the night before. He cooked our dinner for us in his tall hat, cassock, and shirt sleeves, and then put me to sleep in a box at the top of a ladder in one corner of the cafe, which was redolent of stock-fish, and alive with vermin. I wanted no waking next morning, and was pacing the sea-shore long before the eikons had begun their day’s work ; it was fresh and bright everywhere except in Papa Manoulas’ hole.

“To-day was to be the blessing of the ships, and as every Amorgiote, directly or indirectly, is interested in shipping, it was the chief day in the estimation of most. When the procession reached the shore the metropolitan priest of the island entered a bark decorated with carpets and fine linen, carrying with him the precious eikon of the Life-Saving Madonna (Chozobiotissa); he was rowed to each ship in turn, and blessed them, whilst the people all knelt along the shore, and as each blessing was concluded a gun was fired as a herald of joy. The rest of the day was spent in revelry. I was glad not to be going to pass another night under Papa Manoulas’ roof, for I felt sure that it would be dirtier than ever. Friday and Saturday were passed by the eikons and priests in complimentary visits, and liturgies in the numerous churches in and around the town. I did not accompany them on these journeys, and persuaded Papa Demetrios to come off with me on an excursion, for he too was tired of these repeated ceremonials, and was not sorry to transfer his eikon to inferior hands. The week’s veneration for the eikons was at an end, and the Amorgiotes were now prepared for enjoyment. Every one knows the beauties of the Greek syrtos, as the dance goes waving round and round the planetree in a village square, now fast, now slow, now three deep, now a single line, and then the capers of the leader as he twists and wriggles in contortions. Here in Amorgos the sight was improved by the brilliancy of one or two old costumes. One lady especially was resplendent; her ‘tourlos’ was of green and red, her scarf an Eastern handkerchief such as we now use for antimacassars, coins and gold ornaments hung in profusion over her breast, her stomacher was of green and gold brocade, a gold sash round her waist, and a white crimped petticoat with flying streamers of pink and blue silk, pretty little brown skin shoes with red and green embroidery on them. She was an excellent dancer, too, a real joy to look upon. The men wore their baggy trousers, bright-coloured stockings, and embroidered coats; but the men of Amorgos are not equal to the women. The beauty of an Amorgiote female is proverbial.

“My stay in Amorgos ended thus gaily. Next day the relentless steamer called and carried me off to other scenes.”

For an excellent introduction to the Bents on Amorgos, see the site simply called The Cyclades.

(Theodore Bent’s books on the Cyclades and Dodecanese, and Mabel Bent’s Chronicles are available from Archaeopress, Oxford)

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Leave a comment or contact us about this article

Ah – it takes me back to my Easter visit to Amorgos a couple of years ago. Although, obviously, a lot has changed over the intervening years, much of the Easter ceremony is still as Theodore describes it and Amorgos still has the feel of a place at the end of the line, even though the ‘steamer touches here’ more than just once a week now. In fact, the island has its own, much-loved, small boat, the Express Skopelitis, which plies its way back and forth between the island and Naxos Town daily, in all but the most atrocious weather – it’s an experience in itself. Despite being easier of access now, the island still has a very special, unspoiled feel. You can still see the prophetic spring inside the church of St. George Balsimitis (if you ask Sister Irini nicely). The walk from the beautiful Monastery of Chozobiotissa to the northern port village of Aegiali, across the spine of the island, with the sea strait between Naxos on one side and the Ikarian Sea on the other, is breathtakingly beautiful – you’ll see many, many, many goats, but no other people.